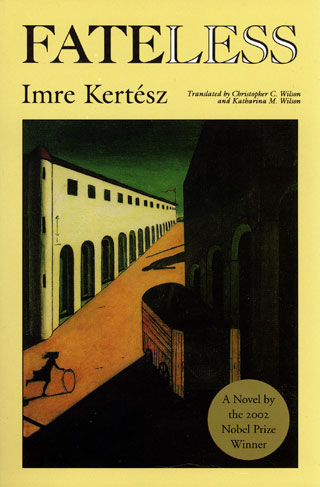

Fateless

Fateless

Imre Kertész

Northwestern University Press, 1992

191 pages

This book review begins on a philosophical note occasioned by the title of the book. The title – Fateless1 – is a lexical construct that is not listed in most English dictionaries but it follows the form of a descriptive word, an adjective. So, the author of Fateless, Imre Kertesz, has in his thinly veiled memoir of his own Holocaust experiences, chosen to give his book an intriguing title that appears to contradict the terrible fate of six million Jews in Europe and the suffering of those that survived…

Kertesz was born in Hungary in 1929, and when he was transported on a German train to Auschwitz, he was all of fourteen years old. The book was first published in 1975 and the fate of one third of the Jewish people, murdered in the Holocaust, was well on the way to receiving canonical status in the tomes dealing with man’s inhumanity to man. The ‘fate’ of six million Jews murdered in Europe because of an ideology became the benchmark for the whole subject of genocide after World War II and the Holocaust.

The boy Imre Kertesz was en route to becoming part and parcel of this tragic fate for the majority of Europe’s Jews, but against all odds he survived to become the adult – author Imre Kertesz. Kertesz presented the world with, amongst other works, this account of his protagonist, George Koves, in this book he called Fateless.

The dissonance created here is deafening.

Does the non-word “Fateless” suddenly become loaded with ominous overtones when applied to the number of six million whose fate generated the term "Genocide," coined in the aftermath of the Second World War and the Holocaust? Is genocidal murder on such an unprecedented scale so incomprehensible that their fate can’t be verbalized? And perhaps, were the author’s experiences such that he could only portray them through a protagonist with another name?

All these questions are definitely a preoccupation of this reviewer’s mindset and they are highlighted by the strange name of the book.

The story presented through the main character George is the harrowing journey of a young fourteen-year-old from the security of his family surroundings in Budapest into the extreme ordeals he undergoes at the hands of the Nazis in Auschwitz, totally devoid of any family context or support. The year is 1944, late in the history of the Second World War and the Holocaust with all the attendant suffering metered out to European Jewry specifically and Europe in general. However, the fact that George Koves and more than four hundred thousand Hungarian Jews will suffer deportation and most will be murdered in less than half a year does not make their suffering less anguished, and the story presented here in Fateless is as difficult to absorb as any story of Holocaust horror.2

The list of trials and tribulations is beyond any reader’s ability to understand. Anyone who wasn’t in a concentration camp is mainly dependent on survivors’ descriptions when attempting to penetrate that reality because the system created by demonic Nazi inventiveness is one of the pinnacles of radical evil. And no average human being could imagine it.3

So Imre Kertesz invents his protagonist, George Koves, to lead us through the mire. The book begins with a description of George’s family and their preparations for his father, who is being shipped off to a labor camp on the morrow. The reader is introduced to various members of his family: father, stepmother, biological mother, uncles and aunts, all of whom are presented in the context of bidding George’s father farewell. Details about family affairs and intrigues abound and one could be duped into thinking that the book will be about some regular family saga with a teenage son growing up and experiencing his first kiss with a neighborhood girl before twenty-five pages are up. In fact, an everyday tone, sentence, and descriptive phrase are part of the uniqueness of this account of radical evil as George’s descent into his ‘fateless’ Holocaust fate unfolds, page after page. Kertesz concludes the first chapter with a stunning last sentence about Koves’s father being taken off to forced labor that provides evidence of this engaging and discombobulating style that pervades the book: “…we were still able to send him, poor dear man, off to labor camp with the memory of a beautiful day.”4

The book continues describing the stages George goes through, from schools closing down to working in labor groups in the city and then to his abduction one day and his ‘disappearance’ into the different points along the route leading to Auschwitz. We witness the way this fourteen-year-old boy deals with the first death he encounters in the cattle-car en route. Again the understated style: “... the old woman finally fell silent…everyone, myself included, thought the event was completely understandable”.5

And then the arrival in Auschwitz. Imre Kertesz lived to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2002, and any reader of the book under review here will understand the considerations of the panel of judges. Auschwitz has been described in various memoirs of survivors and has come under the scrutiny of numerous historians. Tomes on this German camp have been written and yet George Koves and Imre Kertesz lead us through this netherworld of radical evil describing the indescribable with riveting detail: hunger, the failing of the body, a total sense of helplessness and so much more. The reader learns what it is to walk and work in wooden clogs that don’t fit the foot and which stick in the muddy terrain. The list of travails is endless. And yet, and yet it is all described through the eyes - may one call them naïve after all these eyes have witnessed and suffered? - the eyes of a fourteen-year-old who somehow muddles through the nightmare with perhaps a saving mechanism that an older prisoner might not have access to – the advantage of youth. I have read the following sentence many times in an attempt to understand what the author is trying to tell me: “I would so much like to live a little longer in this beautiful concentration camp.”6

Many readers will grapple with this sentence, weighting different words in order to squeeze some meaning out of what appears to be an impossibility. And so the reader of Fateless, is presented with the testimony of a man-made-hell which is eminently readable because of the intriguing style employed by Imre Kertesz and although reading the evidence presented here is not enjoyable, it certainly counts as an immensely enriching experience.

- 1.The original English translation that was published in 1992 - “Fateless” – was later republished with the adjective transformed into the noun – or condition - “Fatelessness”.

- 2.The account of Auschwitz presented to the world by Primo Levi in his well known memoir, “If This is a Man” is based on his ten month stay in that hell, a similar time frame to that of the Hungarian tragedy so that the time span of incarceration is not a main factor but rather the intensity of evil that so predominates in the camp regime.

- 3.In the Holocaust museum of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Roman Frister appears on one of the screens which present the Jewish narrative. As a survivor living in Israel, he chose to tell two stories, one of which is the horrendous story of his not helping his father who had collapsed whilst standing next to him in a morning roll-call in the camp. The reason he shares this story with all and sundry is to permit the uninitiated an access path into this radical evil. He admits that he was afraid of Nazi wrath if he bent down to lift his father up and the story is thus designed to help us understand how every prisoner was capable of being turned into a selfish monster who could even abandon his father.

- 4.Imre Kertesz, Fateless (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1992), trans. Christopher Wilson and Katherina Wilson, p. 20.

- 5.Ibid., p. 55.

- 6. Ibid., p. 138.