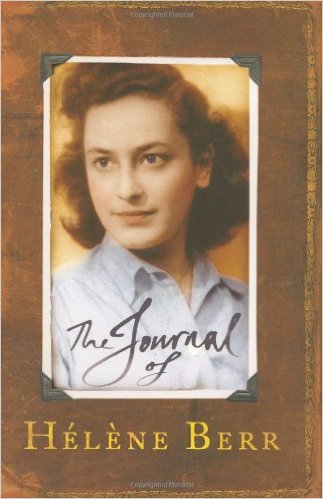

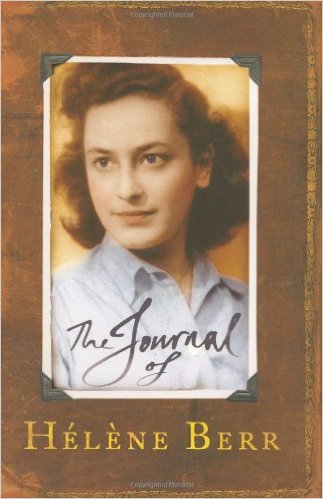

The Journal of Helene Berr

Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

The Journal of Helene Berr

The Journal of Helene Berr

Helene Berr

Weinstein Books, 2008

294 pages

Helene Berr was twenty-one years old when she started to keep a diary. The year was 1942, two years into the German occupation of France. She had grown up in a well-to-do Jewish family with strong ties to Parisian society and some elements of Jewish identity. Immersed in the busy, intellectual pursuits of Sorbonne student life, world events interrupted and with the occupation, an inexorable negative progression was begun which from 1942 is portrayed so acutely in Helene’s diary.

If ever the humanity streaming off the pages of a memoir collided with the human capacity for cruelty, Helene Berr’s Journal would be the embodiment of such a collision. It is a colossal collision and one way of portraying it is simply to juxtapose the raw inhuman experience of German racial policy in France as it was executed in Paris and described throughout the diary to a list appearing on page 295 of the book: ‘Books Quoted or Mentioned by Helene Berr’.

Helene Berr was a gifted graduate student at the Sorbonne in the field of English Literature and the diary she started keeping in the spring of 1942 is sprinkled liberally with references to various treasures of world literature (as on the list above). The resulting dissonances that emerge from quotations of Shelley, or Keats, or Shakespeare on the one hand, and the descriptions of the German deportations of French Jewry from Paris on the other accompany you with an unnerving consistency from start to finish.

What she managed to achieve in her writing is this effective contrast between the external events and her personal story. The diary progresses via four central interweaving threads – listed below – with the mounting tension over the months and years finally leading to the inevitable denouement.

Helene and her parents were arrested in March, 1944 and deported to Auschwitz. Her parents succumbed within months. Helene was transferred to Bergen Belsen where she died days before the British liberated the camps.

The difference in impact between reading an academic historian’s account and a diary is the weight of the personal narrative in which the reader becomes involved. Helene Berr’s story is captivating and heart-rending precisely because it doesn’t try to be.

Following are two short entries:

“Here we had tea on the small table, listening to the “Kreutzer” sonata... He sat at the piano without being asked and played some Chopin. Afterward, I played the violin.”

This entry, from August 11, 1942, relates to an afternoon meeting in the then early romance developing with Jean M., later to become Helene’s fiancée. The growing attachment of these two young people is touchingly referred to as the diary progresses but their personal relationship appears doomed as the bigger narrative of the Nazi deportations of French Jewry unfolds.

“I couldn’t really make out Papa’s note because Maman was sobbing so hard that it stopped me concentrating. For the time being I couldn’t cry. But if misfortune does come, I shall be sorrowful enough, sorrowful for all time.”

This second entry from September 20, 1942, refers to a note sent by Helene’s father, Raymond Berr who was imprisoned in Drancy, a German transit camp where Jews were held before deportation from Paris.

The fear and desperation that had to be omnipresent has to be read in between the lines of the journal as can be seen from this short entry on her father’s imprisonment. The whole journal is written in an engaging style. The apparent naivety in her outlook is balanced by the dangerous volunteer work she does, ameliorating the lot of threatened Jewish children.

We can only be grateful that this sensitive memoir has come to light more than fifty years after it was written.

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue