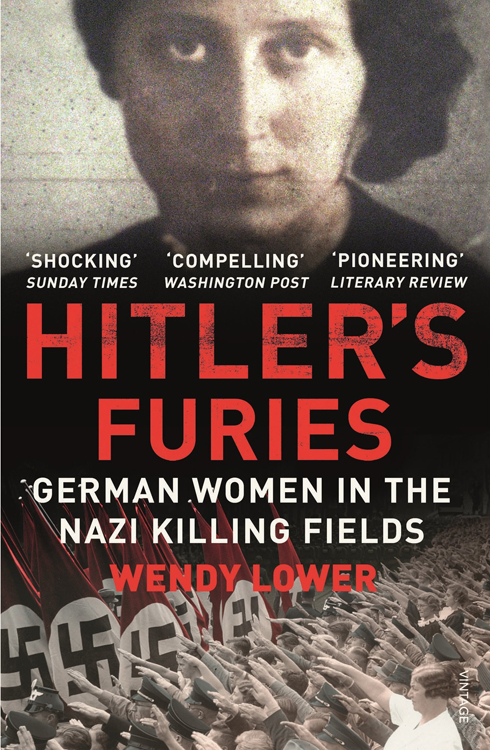

Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields

Wendy Lower

Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013

288 pages

In 1987, Congress officially declared March to be Women’s History Month. Throughout the 2016 presidential campaign, the role of women in American history and contemporary society often took the spotlight in public discourse and on social media.

Echoes and Reflections incorporates a plethora of primary sources focusing on the experience of women and girls before, during, and after the Holocaust, especially the powerful visual history testimonies interwoven throughout the resources. For instance, Margaret Lambert recalls her experience as an athlete in the shadow of the swastika; Esther Clifford talks about Nazi propaganda in the streets; Itka Zygmuntowicz relates to the poem she composed in an extermination camp, and more. An artifact in one of the lessons about the “Final Solution” highlights the story of how Shlomo Breznitz’s mother traded a full day’s ration of bread for a hair comb in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Writing a diary while in the Lodz ghetto, David Sierakowiak noted how his mother agreed that “she had given her life by lending and giving away provisions, but she admitted it with such a bitter smile.” David also notes that “although she loved her life so greatly, for her there are values even more important than life…” A photo featuring a Jewish woman sitting with her children before being executed by the Einsatzgruppen in Lubny, Ukraine, and the poem Holocaust 1944, written by Anne Ranasinghe and poignantly dedicated to her mother, are other examples of the interdisciplinary materials related to gender that are available to educators.

However, women during the Holocaust were not only victims. Most non-Jewish women who lived during this period were passive bystanders. Very few chose to become rescuers like Miep Gies. Echoes and Reflections also sheds light on perpetrators, collaborators, and bystanders. However, our pedagogical focus centers around the personal stories of individual victims who lived during the Holocaust. The decision-making process of the perpetrators is an important educational discussion, especially with older high school students.

In Hitler’s Furies, Professor Wendy Lower presents her research about German women as killers and accessories to murder during the Holocaust. She writes, “The female perpetrators of the Holocaust employed guns, whips, and lethal needles to achieve a mastery that was not otherwise available, to lord it over victims of the regime rendered powerless.”

Lower provides case studies of German women who worked in various professional capacities in the Third Reich, such as secretaries, nurses, and teachers who actively carried out Nazi racist policies in Europe. Educators may find her section on teachers to be of particular interest. Lower explains that, “Schools were central institutions for converting ethnic Germans to the Nazi cause, and for creating a racial hierarchy that pushed non-German children out of the schools while developing a new elite of female educators.” Some of the examples from Chapter 2 of Lower’s book may connect well with the visual history testimony of Judith Becker, who speaks about a course on Nazi racist ideology.

Throughout her book, Lower addresses antisemitism and political indoctrination in detail. For instance, she writes that “It was the Jewish intellectual who spoke of the emancipation of women, Hitler declared in 1934. The Nazi movement would ‘emancipate women from woman’s emancipation.’” She writes about the Nazi youth movement known as the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls), which Julia Lentini described in her visual history testimony. The League of German Girls, similar to the Hitler Youth, promoted a rabidly antisemitic worldview.

German men and women alike exhibited anti-Jewish hatred during this period ―among the onlookers and especially among the perpetrators. For instance, Lower describes how Erna Petri, the wife of an SS officer stationed in Ukraine, decided to shoot Jewish children with her own weapon. Although Petri was a mother of two children herself, she did not consider her young victims to be human beings, but racial pestilence that needed to be eradicated. In the words of Petri after the war “…I had been so conditioned to fascism and the racial laws, which established a view toward the Jewish people. As was told to me, I had to destroy the Jews. It was from this mindset that I came to commit such a brutal act.”

The author relates to a document written by Robert and Ruth Kempner on “Women in Nazi Germany,” research commissioned by the US government during the post-war period. Robert Kempner was an important prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials. Educators using Echoes and Reflections may consider having their students research the Kempners online, especially in conjunction with the handout in Echoes and Reflections on war crimes trials.

Lower states, “Genocide is also women’s business. When given the ‘opportunity,’ women will engage in it, even the bloodiest aspects of it.” Women’s History Month is an apt time to recall that it is important to see women and girls not only as victims in a male-dominated world, but also as agents in both the positive and negative sense. Lower asserts that, “the collage of stories and memories, of cruelty and courage, while continuing to test our comprehension of history and humanity, helps us see what human beings―not only men, but women as well―are capable of believing and doing.”

I highly recommend Hitler’s Furies to the Echoes and Reflections learning community as a source of further study about this topic.