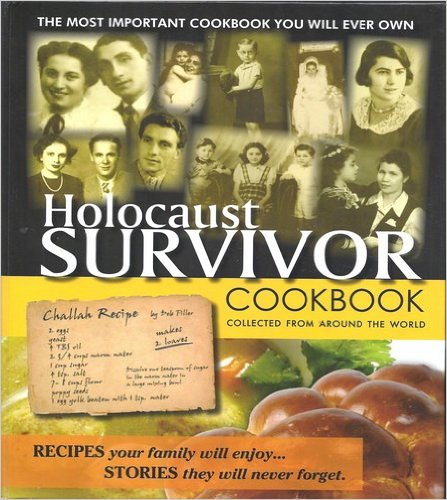

Holocaust Survivor Cookbook – Collected from Around the World

Holocaust Survivor Cookbook

Joanne Caras

Caras and Associates, Inc., 2007

350 pages

As the title might imply, this is not a regular cookbook. In fact, it is quite unusual. Sarah Caras, the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, and her husband Jonathan (new immigrants to Israel from the U.S.A.), have succeeded in collecting 100 stories from Holocaust survivors from many countries all over the world including Argentina, Australia, China, England, Sweden, and the United States.

The authors' mothers Joanne Caras and Gisela Zerykier came to visit their children soon after they moved to Israel. Shortly afterwards, Gisela's mother, who lived in Belgium, passed away, and Gisela's moving tribute to her mother, a Holocaust survivor, was the spark that created the idea for the cookbook.

As found in conventional cookbooks, there is a list of contributors. In this case, most of the women who submitted recipes are Holocaust survivors. There is also a recipe index, divided into various categories such as breads, soups, salads, main dishes, Passover recipes, and more. Accompanying the recipes are photographs of happy families before the Holocaust, and of those who survived, rebuilding their lives and starting their own families.

Reading the testimonies accompanying the recipes gives us insight as to what it was like to have to exist on starvation rations and suffer from undernourishment and malnutrition. During the Holocaust, women often became the mainstays of their families, maintaining their self-respect and applying their strength to obtaining food, whether in their former homes, the ghettos, or camps.

We know that food, or the lack thereof, became a very important focus of the daily life of prisoners in the camps, who fantasized about feasts as they ate their daily meager portions of bread. Sometimes women in the barracks collected and exchanged recipes and took turns to write them down on stolen scraps of paper. Lillian Berliner, from Hungary, describes:

"We were starved in Auschwitz and to alleviate our numerous hunger pangs, we invented frequent 'dream meals' ranging between coffee klatches, luncheons, informal and formal dinner parties. We planned our menus carefully for hours and in great detail. Our favorite dishes and desserts took priority and were frequently repeated. The table settings, the color of dishes, tablecloths, napkins, flowers for each occasion and the seating arrangements were also discussed... This may sound delusional I know, but during these meal planning sessions, we were briefly transported to a normal world, a world that was so far from our miserable reality. We actually tasted the dishes we prepared and our hunger pangs disappeared during the hours of planning. We could hardly wait for the next planning session."

The recipes in this volume have been passed down from generation to generation. However, this book is not only a collection of recipes, but rather a memorial to Holocaust victims, creating a legacy for future generations. Essentially, the memory of their families and friends who did not survive live on through these recipes and are a testament to the courage of the survivors. Each recipe reminds us of the taste of home cooking remembered by the survivors.

Ruth Steinfeld, from Texas, was only seven years old when she was sent away with her sister from the Gurs prison camp in Vichy France. The girls survived, but their parents perished in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Ruth recalls:

"I had no idea even how to make a good soup. I do not remember exactly what my mother looked like, but I remembered the smell of her chicken soup. I worked on it until I felt I had my Mom in my kitchen."

Rita Roitman writes about Geitel Gervic from Poland, noting,

"She was a warm and generous soul and she cooked without recipes. My mother and I would gather around her as she cooked, guessing at the measurements so that we could duplicate her fabulous cooking."

It should be noted that the authors take no royalties from the proceeds of the sale of this cookbook, but donate the money to Carmei Ha'ir, an organization in Israel that serves over 500 meals a day to poor and hungry Israelis, some of whom are Holocaust survivors.

During the interview sessions, the author experienced firsthand the distress and difficulty survivors endured in sharing their stories, many for the first time. Details were often too painful to recall, and several survivors have explained the inadequacy of language to convey the sights, sounds, smells, humiliation, degradation, and sheer terror endured. Also, given the challenge of building new lives in the austerity of the post-war world, survivors were often too busy to dwell on the past, and if they wished to speak, few seemed willing to listen.

Despite the brutality and degradation endured, these testimonies are not just images of darkness and despair. Instances of mutual support, goodness, and small gestures of reciprocated kindness are recalled as well. There are countless examples of how, even in the most cruel circumstances, people held firm to their humanity and steadfastly clung to the values that their parents and communities had bequeathed them. Even "Jewish humor" persisted.