- Gusta Davidson Draenger, Justyna's Narrative, Eli Pfefferkorn, David H. Hirsch, eds., Roslyn Hirsch, David H. Hirsch, trans. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996), p. 33.

- Justyna was imprisoned by the Nazis after surrendering to them. She and her husband, Shimshon (Szymek) Draenger, one of the heads of the Akiba movement in Krakow, had made a pact: if one of them was arrested, the other would voluntarily give themselves up to the Germans. When Szymon was arrested after the Cyganeria operation (see another article in this newsletter on resistance in Krakow for more information), Justyna set out to search for him. Her search led her to the Gestapo who, when they discovered her relationship with Szymek, arrested her as well in January 1943.

- Justyna's Narrative, p. 13.

- Ibid., p. 35.

- Ibid., p. 75.

Justyna's Narrative

Justyna's Narrative

Gusta Davidson Draenger

University of Massachusette Press, Amherst

144 pages

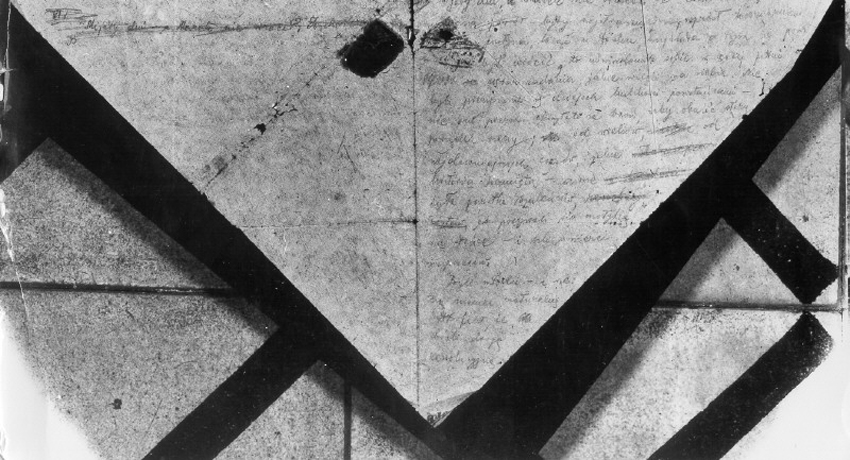

“From this prison cell that we will never leave alive, we young fighters who are about to die salute you. We offer our lives willingly for our holy cause, asking only that our deeds be inscribed in the book of eternal memory. May the memories preserved on these scattered bits of paper be gathered together to compose a picture of our unwavering resolve in the face of death".1

…. "Justyna" – Gusta Davidson Draenger. January, 1943, Montelupich Prison

- 1. 1

This book, Justyna's Narrative, is Gusta Davidson Draenger’s account of the activities of the Cracow Jewish Resistance, especially the Akiba youth group to which she belonged. It is actually like a diary of events, and was first published in 1946, in Polish. Gusta only uses Polish code names for the Akiba group members in her diary, so as not to endanger them. Her code name, "Justyna," is used throughout the narrative and throughout this review.

Justyna wrote her account while sitting in prison and waiting to be executed, in the first months of 1943.2 These circumstances make her account all the more remarkable. She wrote her diary secretly, on pieces of toilet paper, and later on pieces of paper smuggled into the prison. Prison wardens were known to barge into the cell unexpectedly, so Justyna sat by the barbed wire window, writing, whilst her cell mates huddled around her. She knew her days were numbered – at any time she could be taken out of the cell and murdered. She wanted the world to know about the activities of the Akiba movement, and other youth organizations in Cracow, Poland, during World War II. When her fingers were too tired to write, she dictated to her cell mates. In order to make sure that her narrative would be preserved, four copies of it were written out by hand. Jewish auto mechanics who worked for the Gestapo and were housed in the prison at night smuggled writing material to the women in the cell and were able to smuggle out some of the notes. Two complete sets of notes were hidden in the prison, and another two were smuggled out, of which one survived.

In the prison, Justyna became a role model and spiritual influence. For example, she convinced her fellow inmates to wash and brush their hair, and to keep the cell clean. Here below is an example of spiritual resistance even in the most dire of circumstances. Genia Meltzer who settled in Israel, describes Justyna’s influence on her cell mates:

“I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t drink. I couldn’t communicate at all with the others. I just sat along in the corner of the cell, trying to regain my bearings. ……. the natural tendency was to surrender yourself to the place, to give up your humanity. But Gusta’s leadership prevented us from succumbing. Although she firmly believed that we could expect nothing but an early and violent death, she didn’t let us neglect ourselves. She made us wash and brush our hair every day, as long as the water lasted and she made certain that the table was cleaned every day…….. she never believed that we would survive the place. But she felt that whilst we were alive, we should behave as human beings….”3

Justyna's diary covers four stages (about four months), of the Akiba movement’s history.

In the first part she describes how a delegation from the Jewish Self-Help Society in Nowy Wisniz sent a letter to the chief of the Gestapo requesting approval for a series of courses to be offered for the purpose of training the Jewish youth to do farm work, and permission to establish a farm in Kopaliny. In December 1941, having received permission, ten of the most trusted students, including Justyna and her husband Szymek Draenger, were assigned to Kopaliny. During the day they undertook farming training (hachshara), in preparation for immigration to the land of Israel, but at night they mailed out bulletins disseminating information about what was really happening to the Jews, and they would also discuss how and whether to organize active resistance against the Nazis. In August 1942, the group had to close down its activities in Kopaliny after rumors of their activities spread. Despite the ever-present danger, Justyna had more pleasant memories of that time. She wrote,

"The sun was sinking behind the forest, which extended from the outskirts of the mansion into the distance like a dark stain till it fused with the Blue Mountains in the far-off horizon. The stillness hovering luxuriantly above the orchard spread itself across the golden fields, lay down indolently in the dense pastures, circled the mansion, and expired in the boundless forest. Summer was at its peak. No one had returned yet from the fields. As far as the eye could see, not a soul disturbed nature's stillness with even the slightest movement. All creation seemed suspended in the heat of the summer day. In the profound silence, it was easy to forget that war was raging and blood being spilled, that violence, evil, brutality, lawlessness, human injury and pain existed on this earth".4

Like the other Jews of Cracow who remained in the city at the beginning of 1941, Justyna was forced to move into the Cracow Ghetto, which she calls "the quarter". She was happy to be living amongst her friends again, and describes the attempts of the group to organize themselves into a fighting unit. In an entry that shows the change among the youth of Akiba, who had once been involved only with education and issues of social welfare, Justyna writes,

"History will never forgive us for not having thought about it. What normal, thinking person would suffer all this in silence? Future generations will want to know what overwhelming motive could have restrained us from acting heroically. If we don't act now, history will condemn us forever. Whatever we do we're doomed, but we can still save our souls. The least we can do now is leave a legacy of human dignity that will be honored by someone, some day." 5

From this and other entries, it is clear that Akiba was metamorphosing into a movement that would take active, armed resistance against the Germans. Justyna writes about the trials and errors of the new fledgling fighters and how many of them lost their lives purely through lack of experience and equipment. They tried to gather weapons, and make bases in the forest, and a first group of six brave Akiba members were sent into the forest. Unfortunately the inexperienced fighters were soon seen and reported to the German police. Eventually, only one fighter, Zygmund Mahler, returned. The group of six did not have enough weapons to defend themselves, and from this tragic experience, they had to learn by their mistakes. This is the second stage of the diary.

In the third stage, Justyna depicts the actual armed struggle. Operating in Cracow, the Jewish resistance succeeded in carrying out several attacks on the Germans, including throwing grenades into the Cyganeria coffee shop, but after this successful resistance operation, members of the group were tracked down and arrested by the Gestapo.

It was the custom of the Akiba Youth Movement in post-World War I Poland to assemble on Friday nights to celebrate the onset of Shabbat. In 1941, these gatherings took place inside the Cracow Ghetto. As the friends sat together on the Friday night of November 20, 1942, Aharon Liebeskind (Dolek), the spiritual leader of Akiba, who was later killed, had a premonition and uttered the words, "This is the Last Supper." He felt that this would be the last time they would greet the Shabbat together. This indeed was the last evening at the Akiba meeting place at Jozefinska Street, remembered as "The Last Supper."

The last part of the diary describes the collapse of the movement, and the hunting down of its fighters.

Miraculously, Justyna and her husband Szymek each managed to escape from the Montelupich prison convoys (Szymek from Montelupich, and Justyna from a different part of the Montelupich complex, the women's prison at Holtzlow Street) as they were separately being led away to be shot, on the very same day in April, 1943. They were reunited in the town of Bochnia, where they and other Akiba youth members continued their resistance against the Nazis.

It is not clear exactly how Justyna and Szymek met their deaths; this part of the story is cloaked in mystery. We know that they resumed publishing an underground newsletter from the town of Bochnia urging the Poles not to cooperate with the Germans and trying to convince the Jews to resist and not submit to their deaths passively. However, at the beginning of November, 1943, both were captured by the Germans. Their capture and apparent deaths spelled the end of the great Jewish fighting organization in Cracow.