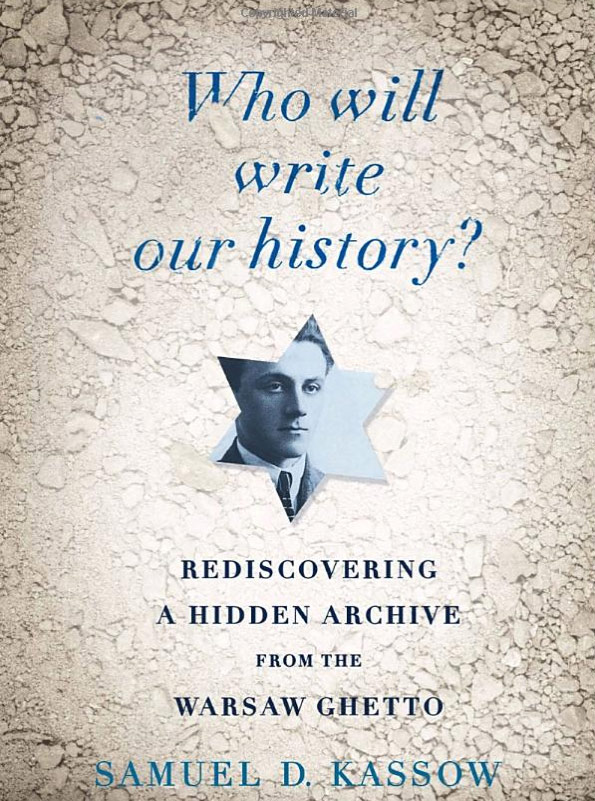

Samuel Kassow

Indiana University Press, 2007

568 pages

Who Will Write Our History is a fascinating study of three separate and intertwined subjects: at its heart is Emanuel Ringelblum, the historian who had the prescience to create and encourage the keeping of an archive in the Warsaw ghetto during the Holocaust. His story cannot be told without reference to the archive itself, which Ringelblum called “Oyneg Shabes” (the joy of Sabbath), primarily because its management committee met secretly to discuss the archive on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath. In the Warsaw ghetto, where the archive was assembled and ultimately buried in the ground to protect it from the destruction of the ghetto by the Nazis, this was no mean feat – the archive was born at a time when it was difficult enough for individuals to keep body and soul together, never mind dedicating themselves to a project – more like a mission – that was much bigger than they were.

In writing this book, Samuel Kassow portrays the story of one individual – Ringelblum – in the larger context of the community he created. The archive Ringelblum took pains to put together is nothing short of miraculous: it is our greatest single source of information about the Warsaw ghetto. But the story of its creation is a real story of the individual and the community during the Holocaust: though Ringelblum, as a historian, envisaged a way in which the history of the Jews in Warsaw during the dark period of the Holocaust could be recorded and salvaged, he could not have done this without creating a community of other individuals who, like him, cared about Jewish history and about writing it all down. The dozens of men and women that he brought together, a group Ringelblum called “the sacred society”, birthed the “legend”, as he referred to the archive itself. They all believed in the cause that united them. Nineteen-year-old David Graber, one of the boys who helped to bury the archive at the beginning of August, 1942, at the height of the murderous frenzy that would result in the deaths of almost 300,000 of the ghetto occupants at the hands of the Nazis in Treblinka, scribbled a “last will” that was found with the archive:

What we were unable to cry and shriek out to the world we buried in the ground….I would love to see the moment in which the great treasure will be dug up and scream the truth at the world. So the world may know all…May the treasure fall into good hands, may it last into better times, may it alarm and alert the world to what happened…in the twentieth century….We may now die in peace. We fulfilled our mission. May history attest for us.

Kassow first discusses Ringelblum himself, the pivotal individual without whom the archive would not have existed. Ringelblum conceived of the archive, shaped it and pushed hard to bring it to fruition, encouraging other individuals to write as much as possible, to keep documents that included official posted notices as well as candy wrappers. Ringelblum had been trained and influenced by the first modern historians of Eastern European Jewry, Simon Dubnow and Isaac Schiper, as well as Meyer Balaban. These historians felt, as did Ringelblum, that Jewish history should be a source of pride and a way to preserve Jewish identity, especially among secular Jews who rejected assimilation and religion. For Ringelblum, the question, “Who will write our history?” was a critical one. He believed that for far too long, gentile historians had given the Jews short shrift, and that it was time to stop limiting Jewish history to the sayings of rabbis or the actions of the rich; that day-to-day Jewish life needed to be reclaimed by the Jewish historian. Ringelblum’s solution was for ordinary Jews to write their own history – for armies of zamlers (collectors) to collect material, write their own autobiographies and believe that their lives were worth examining. Because this was his philosophy even before he and almost half a million other Jews were penned up together in the Warsaw ghetto, he was the right man to establish the largest ghetto archive during the period of the Holocaust.

Kassow discusses the team of courageous individuals who worked together with Ringelblum on the archive. Tellingly, he calls them “a band of comrades” for whom a shared sense of national mission trumped narrow individual agendas. There were those who had been prominent Jewish leaders before the war; there were those who were merely impoverished refugees; there were rabbis, artists, businessmen and many others. But all these individuals had the community in mind. As Ringelblum himself wrote,

The members of the Oyneg Shabes constituted, and continue to constitute, a united body, imbued with a common spirit. The Oyneg Shabes is not a group of researchers who compete with one another but a united group, a brotherhood where all help one another…Each member of the Oyneg Shabes knew that his effort and pain, his hard work and toil, his taking constant risks with the dangerous work of moving material from one place to another…that this was done in the name of a high ideal….The Oyneg Shabes was a brotherhood, an order of brothers who wrote on their flag: readiness to sacrifice, mutual loyalty and service to [Jewish society].

The Oyneg Shabes archive itself grew out of the self-help organizations in the ghetto – particularly the “Aleynhilf” (literally, “self-help”), and the house committees – organizations which themselves point up the struggle of the individual within the community, and the community itself, to survive in the Warsaw ghetto.

Of course, the archive is so important because it sheds so much light on the lives of everyday people in the Warsaw ghetto. The book contains stories of the deprivations suffered by the inhabitants of the ghetto, but at the same time, it contains the jokes, songs and rumors that allowed the Jews in the ghetto to maintain their morale and their dignity. These are the most fascinating parts of the book – descriptions of the essays written about the role of the Jewish woman during the ghetto, stories written about hunger, street scenes observed and written down to be saved for posterity.

Who Will Write Our History is packed with information, delivered in a straightforward fashion but with a great deal of empathy, as well. Through this book we learn much about the individuals behind one of the most ambitious and amazing collective missions during the Holocaust. The book is required reading for anyone who wishes to get acquainted with the Jewish community that existed in Warsaw, as well as the community that existed in the Warsaw ghetto. Kassow’s book, like Ringelblum’s archive, stands as a tribute to what strength of spirit can accomplish.