Materials and Instructions

Materials needed for this ceremony: copies of passages to be read aloud (those below), distributed by the facilitator to the students. We recommend choosing two (2) narrators and seven (7) readers. The narrators will read all specified texts, whereas the readers are each assigned words of certain children.

We suggest that prior to the ceremony, students create an exhibit from the Pages of Testimony of children who perished during the Holocaust. Images of the children's Pages of Testimony can be pasted on one side of a poster board and displayed at the entrance to the ceremony. The students can light a candle in the memory of each child as they enter the room.

Alternatively, a dark room with candles can be prepared. In this room, children's names, ages, and places of origin will be read out. The students can be asked to memorize two or three names and light additional candles in their memory. A space of this design is reminiscent of the Children's Memorial at Yad Vashem.

Opening

Narrator 1:

January 27th, the day of the liberation of the Auschwitz extermination and concentration camp, is marked annually throughout the world. Over one million Jews were murdered in gas chambers, with starvation, disease, by gunshots, and through backbreaking labor. The vast majority of the victims were unaware of their destination and of their fate, as they were transported to the camp in cattle-cars, arriving in a state of total collapse. Historian Yisrael Gutman wrote, "Never will there be people innocent of all sin as were those victims who stood on the threshold of the gas chambers."

Narrator 2:

Jacob was seventeen years old when he reached Auschwitz.

Reader 1:

"The 'Lager Fuhrer' [head of the concentration camp] said to us: 'From now on, you are all numbers. You have no identity. You have no name. All you have is a number. Except for that number you have nothing.'"

Narrator 2:

There are no graves or memorial sites for the more than one million people who were murdered in Auschwitz. This was the ultimate insult by the Nazis who wanted to deprive their victims of any identity or uniqueness.

Note to the Teacher: Explanation of the Pages of Testimony

The Pages of Testimony that have been gathered by Yad Vashem are submitted by the families or acquaintances of victims. They contain key biographical details about victims, their families, their lives, and those who submitted the Pages of Testimony. While the Pages of Testimony serve as a symbolic memorial, they also portray the victims' personal life stories in a broader historical context.

To Date, over two million Pages of Testimony have been submitted at Yad Vashem. Pages of Testimony and related material can be searched and browsed on the Yad Vashem website.

At this point your students will read Pages of Testimony of children who were murdered at Auschwitz. In preparation you can download Pages of Testimony from Hungary, Germany, Poland, Lithuania, Romania, etc. from the Yad Vashem website.

Suggestions for Reading the Pages of Testimony

Pages of Testimony can be distributed to the students in the audience, and each can stand up and read what is written on the page while carrying a lit candle. At the end of the reading, the student could put the Page of Testimony in a special place that will serve as an exhibition. It is recommended that the Pages of Testimony be given out ahead of time so that students can practice reading them aloud.

Jewish Life Before the Holocaust

Narrator 1:

One and a half million Jewish children were murdered during the Holocaust. Who were they? Where did they live? What did they like to do? The Nazis tried to deprive them of their identity and turn them into faceless numbers during this great tragedy. In the next part of the ceremony, we will deal with the lives of the children prior to the Holocaust, and in this way we will restore their identities.

Narrator 2:

Eva Heyman, a 13-year-old girl from Hungary, wrote in her diary:

Reader 2:

"I've turned thirteen, I was born on Friday the thirteenth... From Grandma Racz, I got a light tan spring coat and a navy blue knit dress. From my father, a pair of high-heeled shoes... Until now I have always worn only flat-heeled shoes... From Grandma Lujza, three pairs of pajamas, a dozen colored handkerchiefs and candy... From Grandpa, phonograph records of the kind I like... My grandfather bought them so that I should learn the French lyrics... I know Hungarian and German well, I've forgotten Rumanian, and I'm beginning to be good in French... I do a lot of athletics, swimming, skating, bicycle riding, and exercise. I also do rhythmics with Klari Weisz, but I don't care for that... I've written enough today. You're probably tired, too, dear diary."

Narrator 2:

Erika Amariglio from Salonika, Greece wrote:

Reader 3:

"In 1924, my father, Salvator Kounio, then twenty-four, already had a small shop where he sold photographic equipment... He acquired many good customers right from the start... In 1924, through a mutual friend, he met Hella Loevy, a third-year medical student at the University of Leipzig. They fell in love at first sight, and my mother decided to abandon her studies and follow him to Greece...

Mother, brought up in Vienna and Karlsbad in Austro-Hungary... suddenly found herself in a world totally different from her previous one. In the 1920s, Thessaloniki was really unlike the rest of Europe... Our house on Koromila Street was built by the sea... A most beautiful staircase led upstairs to the bedrooms. How many times my brother and I slid down the solid banister! Underneath in the basement was the coal cellar and the wood cellar... This served as our hiding place when we played hide-and-seek."

Narrator 2:

Moshe Flinker was born to a religious family in the Netherlands. With the outbreak of World War II when he was 13, his family fled to Belgium. He kept a diary in which he related what happened to him and his family.

Reader 4:

"For some time now I have wanted to note down every evening what I have been doing during the day. But, for various reasons, I have only got round to it tonight... I was born in The Hague, the Dutch Queen's city, where I passed my early years peacefully. I went to elementary school and then to a commercial school, where I studied for only two years."

Reader 1:

Don't They Know the World Stopped Breathing? / Anonymous

And once,

there was a garden,

and a child

and a tree.

And once,

there was a father,

and a mother,

and a dog.

And once,

there was a house,

and a sister,

and a grandma.

And once,

there was a life.

Experiences of Children During the Holocaust

Narrator 1:

Daily life for children was disrupted with the German occupation. The circumstances and decrees varied in differing countries, yet daily life, as such, continued. Children reacted differently to the changing circumstances depending on their age, culture, and individual natures.

Reader 4:

"During the year I attended [the Jewish school], the number of restrictions on us rose greatly. Several months before the end of the school year we had to turn in our bicycles to the police. From that time on, I rode to school by street-car, but a day or two before the vacations started, Jews were forbidden to ride on street-cars. I then had to walk to school, which took an hour and a half. However, I continued going to school during the last days because I wanted to get my report card and find out whether I had been promoted to the next class. At that time I still thought that I would be able to return to school after the vacations."

Reader 2:

"April 5, 1944... Later, in the afternoon, on my way to Grandma Lujza, I met some yellow-starred people. They were so gloomy, walking with their heads lowered... Still, I noticed Pista Vadas. He didn't see me, so I said hello to him. I know it isn't proper for a girl to be the first to greet a boy, but it really doesn't matter whether a yellow-starred girl is proper or not... [Grandma Lujza] says she doesn't even care if she dies. But she is seventy-two, and I'm only thirteen. And now that Pista Vadas spoke so nicely to me I certainly don't want to die!"

"April 7, 1944... Today they came for my bicycle. I almost caused a big drama. You know, dear diary, I was awfully afraid just by the fact that the policemen came into the house. I know that policemen bring only trouble with them, wherever they go... So, dear diary, I threw myself on the ground, held on the back wheel of my bicycle, and shouted all sorts of things at the policemen: 'Shame on you for taking away a bicycle from a girl! That's robbery!' We had saved up for a year and a half to buy the bicycle... One of the policemen was very annoyed and said: 'All we need is for a Jewgirl to put on such a comedy when her bicycle is being taken away. No Jewkid is entitled to keep a bicycle anymore. The Jews aren't entitled to bread, either; they shouldn't guzzle everything, but leave the food for the soldiers.' You can imagine, dear diary, how I felt when they were saying this to my face."

Note to the Teacher

More about children's experiences during the Holocaust can be learned from the following extracts; you can choose passages according to the nature of your ceremony.

Reader 5:

"I feel as if I am in a box. There is no air to breathe. Wherever you go you encounter a gate that hems you in... I feel that I have been robbed, my freedom is being robbed from me, my home, and the familiar Vilna streets I love so much. I have been cut off from all that is dear and precious to me." – Yitskhok Rudashevski, age 15, Vilna, Lithuania.

Reader 6:

Rachel Auerbach wrote from within the Warsaw Ghetto:

"The nine-year-old told the five-year-old about the Helzanki Garden in Warsaw. The story sounded like a fairy tale. 'Such a big garden, so big, so big, and you went in without paying an entrance fee.' 'There were paths and flower beds and a pond with swans.'"

Pepa Bergma, 14 years old during the war, wrote,

"...and here a poor woman in torn, worn-out clothes, bloated by hunger, is lying as if dead in the street. I can't look at her; I turn my face away... These are the street scenes that I see every day."

Shalom Eilati, incarcerated in the Kovno Ghetto (Lithuania) at eight years old, recalled:

"One day my mother didn't come back from work [the forced labor she had been forced to do]... Immediately I took my sister and we went looking for her... We felt like two fledgings whose mother, who had always protected and shielded us, had suddenly disappeared and left us to the relentless sun and to threatening dangers. We had never before felt so abandoned, so alone."

Reader 7:

Hadassah, age 16, from Poland, recounts:

"I think they heard the baby crying, and that brought them as far as our hiding place. Let the child go, he hasn't done anything, he's only a baby! ...But the murderer's heart of stone was not moved. He replied: 'He's a baby now, but he'll grow up to be a Jewish man. That's why we have to kill him.'"

Deportation to Auschwitz

Narrator 1:

Most Jews deported to Auschwitz were murdered in the gas chambers minutes or hours after their arrival. Eva Heyman and Moshe Flinker were two of those victims. Eva Schloss, Cila Liberman, and Erika Amariglio survived the camp, but lost their families, friends, and acquaintances. They lost a considerable part of themselves there too: their individuality, their childhood, their innocence, and their faith in the world.

Reader 1:

Written in Pencil in the Sealed Freightcar / Dan Pagis

Here in this carload

I am Eve

With my son Abel

If you see my older boy

Cain son of Adam

Tell him that I...

Reader 2:

"May 30, 1944... We even know already that we can take along one knapsack for every two persons. It is forbidden to put in it more than one change of underwear; no bedding. Rumor has it that food is allowed, but who has any food left? …It is so quiet you can hear a fly buzz... Dear diary, I don't want to die; I want to live even if it means that I'll be the only person here allowed to stay. I would wait for the end of the war in some cellar, or on the roof, or in some secret cranny. I would even let the crossed-eyed gendarme, the one who took our flour away from us, kiss me, just as long as they didn't kill me, only that they should let me live. Now I see that the friendly gendarme has let Mariska come in. I can't write anymore, dear diary, the tears run from my eyes, I'm hurrying over to Mariska..."

Reader 3:

"It was pitch dark and huge spotlights pierced the darkness, blinding us. 'Steigt schnell aus!' ['Climb out at once!'], they were blinding us. 'Schnell! Schnell!' ['Faster! Faster!'] – but nobody understood. Stunned by the long journey, stiff, hungry, frightened, desperate, everyone tried to jump out of the railroad cars... The cold was terrible, it froze our faces, hands and feet. We were chilled to the bone. Mothers held their babies tightly in their arms, and the older children clung to their skirts. Father. Confused and frightened like the rest of us, pushed us to one side. 'Don't move from the spot,' he told us. The Germans shouted out orders: 'All the children, the elderly, the ill, and the women go to this side.' That side? There were trucks waiting there. They stopped my father, who was about to push us towards the crows going to the trucks. The SS-man asked him, 'Are you and your wife the ones who speak German?' 'Yes,' answered father and added, 'My children also speak very good German!' The SS-man sized us up and asked sullenly, 'How old are they?' This time father made us two or three years older, insisting, 'They are seventeen/eighteen.' 'Wait here until I come back,' the SS-man told us. People continued to get into the trucks, which, as soon as they were full, drove off. Where were they going? We had no idea! How many tragic scenes remain unforgettable in my mind. Mothers whose children were taken away – running after them so that they wouldn't be separated. Old people calling to a child who remained behind. They snatched a young woman's baby by force and pushed her to the other side. Screams, sobs, farewells. And the smartly dressed SS-men shouting and raging in their midst. Suddenly all was silent. Nearly all the people were gone, only a few men and women remained. The SS-men formed them into columns, five abreast, men and women separated. They ordered them to march: 'Vorwarts! Marsch! Schneller! Los!' ['Forward! March! Faster! Get moving!'] We heard them shouting until we lost sight of them. Only the four of us remained. Everything had happened so quickly! All the people who got off the train had disappeared with the trucks. None of our traveling companions were there anymore, there was just us and some SS-men. The silence was overwhelming in the dark night. The spotlights that had turned night into day were switched off."

Design Suggestions for the Conclusion of the Ceremony

While reading the final testimonies about the fate of the children and their families, it is very important that the end of the story/testimony be told tactfully and sensitively in order not to dull the emotions. How the ending is portrayed will determine how the students look upon the victims. Using softer language will create a sense of understanding and empathy. Minimalism could actually emphasize the loss more acutely.

For instance:

- Screen the photograph of the child and blur it until it disappears.

- Write on a slide (or on the photograph of the child that is being screened) what happened to the child and his family.

- Soft music can assist in creating the appropriate atmosphere.

- Read the child's fate aloud while the pupil who played the part lights a candle in his memory and in memory of his family.

Narrator 2:

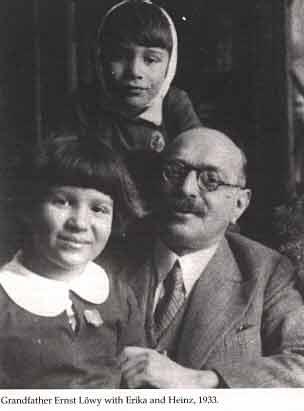

Erika and her mother survived various camps, and after the Holocaust they managed to find her brother and father, who had also survived.

Eva Heyman's parents managed to flee to Switzerland, but Eva was captured and sent to Auschwitz with her grandparents. They were murdered there.

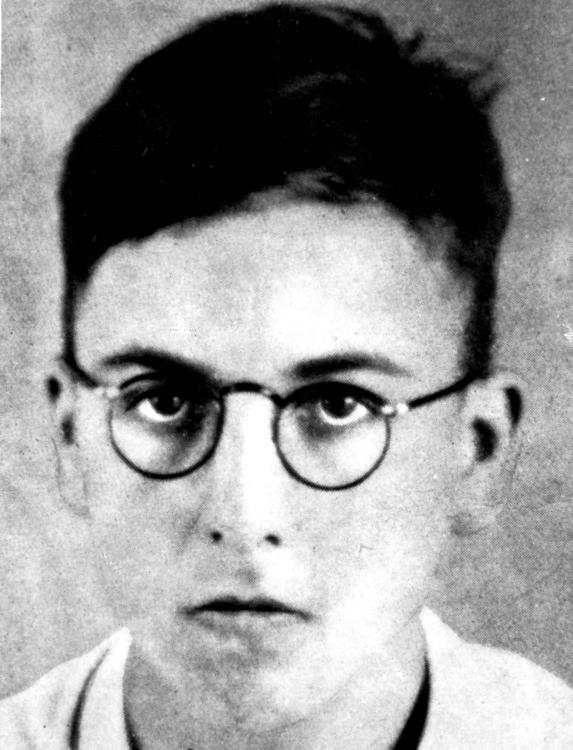

Moshe and his family were captured in Belgium and sent to Auschwitz, where Moshe was murdered.

Six million Jews were murdered on European soil between 1939 and 1945 in concentration camps and death camps, in forests, by starvation, hard labor, and disease.

The Legacy

Narrator 1:

We remember the legacy of those who survived as well as those who did not.

Reader 3:

"Today I have seven grandchildren: Lior, Iris, Tomer and Omri, Charles, Erika, and David. For my grandchildren and all the children of the world of any religion, I have written my testimony fifty years later so that they will be able to reply to anyone who dares to deny there was a Holocaust and so that they will always be on guard to make sure that there will never again be another Holocaust: NEVER AGAIN."

Narrator 2:

Donia Rosen was 12 when she hid in the forest after her family was murdered. Donia survived and immigrated to Israel. The following are words she wrote in her diary:

Reader 7:

"Words fail me, but I must write, I must. I ask you not to forget the deceased. I beg and implore you to avenge our blood, to take vengeance upon the ruthless criminals whose cruel hand has deprived us of our very lives. I ask you to build a memorial in our names, a monument reaching up to the heavens, that the entire world might see. Not a monument of marble or stone, but one of good deeds, for I believe with full and perfect faith that only such a monument can promise you and your children a better future."

Narrator 1:

We must remember so that it will not happen again.