Materials and Instructions

Materials needed for this ceremony: copies of passages to be read aloud (those below), distributed by the facilitator to the students. One student, or the teacher, may narrate. Eleven students are assigned reading parts: seven to the various quoted passages by children, and four to read the poems. We suggest adding appropriate music, such as classical compositions, in order to create a suitable atmosphere.

The Ceremony

Narrator:

This ceremony is designed to highlight human reactions of people trapped in the inhuman conditions that were forced on vast populations during World War II. A spotlight will be aimed specifically on the world of the ghettos, where hundreds of thousands of Jews were imprisoned before deportation to their deaths in extermination camps. Conditions in the ghettos created by the Nazis were extremely difficult and their impoverishment touched on every phase of their new reality.

The diary entries and testimonies will highlight the ways Jews in ghettos tried to maintain their humanity in the face of unprecedented inhumanity.

Through this, we can understand how the human spirit has the potential to be greater than anything that can be done to it.

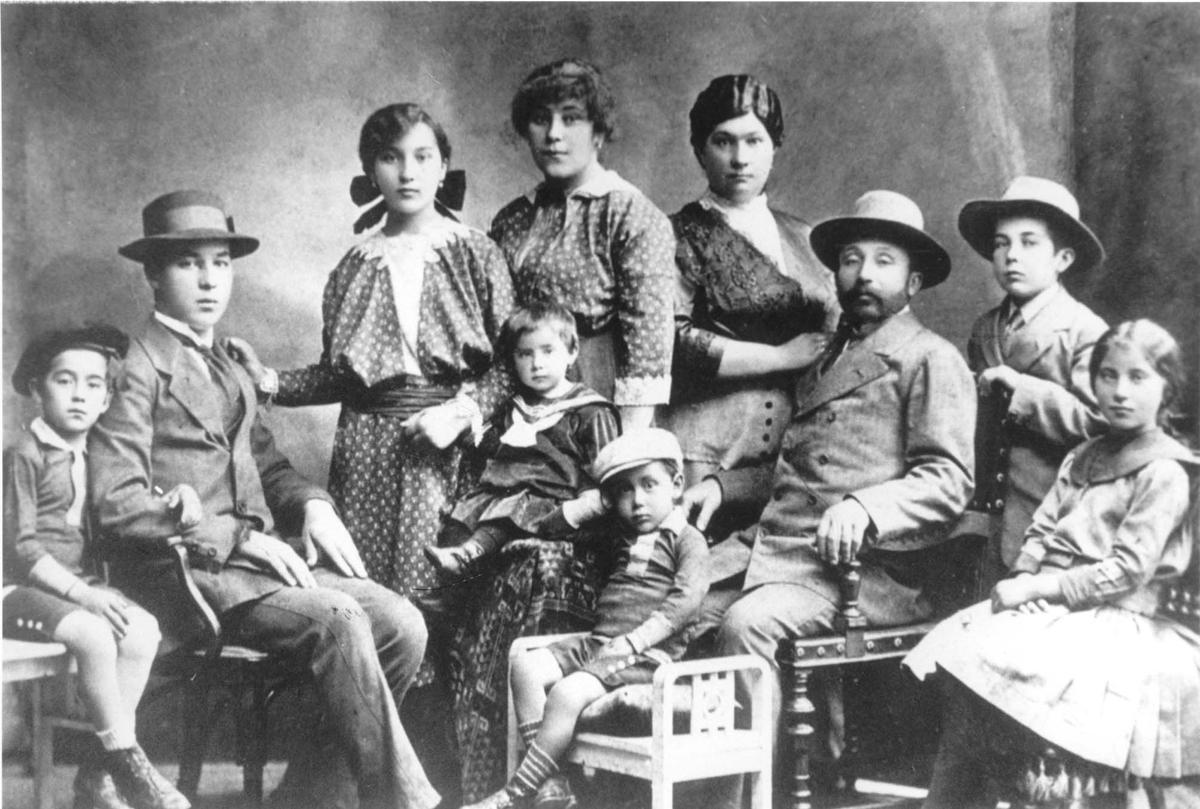

It is important to remember the normal life that these people led before the tragic events of the Holocaust unfolded.

We invite you to come back in time with us as we hear the voices of Polish Jewish children, who, 65 years ago, were around the same ages that you are today.

The following three diary entries of young Jewish girls in Poland, will give us a glimpse into their prewar lives.

Miriam, age 14:

"We were a warm family whose life followed a quiet, carefree routine. We were all born in Bialystok and our roots reached back generation upon generation, living there amidst friends, neighbors, and acquaintances. With this loving background, the years flowed peacefully during the childhood days of my sister Sonyaleh and myself."

Liliana, age 12:

"While the older folks were buying, we children tasted. The farmer's wife was always ready to give the children big slices of fresh wheat bread spread with the best-smelling butter and a little salt on top. If this was not enough to satisfy our enormous appetites, there were apples and pears on the trees nearby. 'Pick as many as you can eat,' said the lady farmer. 'The ones with the red cheeks are the ripe ones.'"

Hanna, age 14:

"Once my homework was done, I liked to play using dolls as models for dresses I designed and made. Reading was my favorite activity... I attended ballet classes, and in the winter, ice-skating was my favorite pastime. As I skated on icy ponds, I frequently imagined myself as a great ice skating dancer performing for large audiences."

Narrator:

All of this changed in 1939.

The German army invaded Poland, and normal everyday life for both the Polish population as well as for the Jewish people changed dramatically, as everyone in Poland began to suffer the effects of German occupation. The Germans established ghettos throughout the occupied countries, and forced Jews from smaller towns to move into the poorer areas of the larger towns. The ghettos were very overcrowded, some were sealed, which meant that freedom of movement had dramatically changed. Jews suffered terrible deprivations such as food shortages which led to starvation, disruption of family life, and, later on, the constant threat of deportations and death.

Yet, despite the hardships and difficulties of daily survival, there were those who found the time and strength to assist others. Eliezer Ayalon, who lives in Jerusalem today, was 13 years old when the war broke out; he speaks about his mother's ability to heal others in spite of the terrible conditions of the Radom ghetto.

Eliezer:

"My mother was known not as a professional nurse, but she healed people in her own way. She used to be called very often to deal with splinters, and she was known as the specialist on how to take these splinters out. She had a little box with needles and pins and she always used to be called and did it in such a professional way. She did it for nothing. She just helped the neighbors – she felt that she wanted to contribute and do something for them."

Narrator:

Miriam, from Bialystok, whose happy childhood we just heard about, continues the description of her family's living conditions after the Germans forced Jews into the constricted area of the Bialystok Ghetto.

Miriam:

"The Germans ordered the Jews to live 'closer' together, and so the Bialystok ghetto was set up. The limited ghetto area, extending over only a few streets, was too small to contain the town's Jewish population, and the overcrowding was terrible right from the beginning. Our family was allotted half a room in the apartment. Nine families crowded into the apartment. Thus we found ourselves together with the entire Jewish population of Bialystok."

Narrator:

In stark contrast to Liliana's happy description before the war, the reality of hunger and attempts to find more food in and out of the ghetto have been immortalized for the generations after the Holocaust by Henryka Lazawart. Henryka was a young Polish Jewish poet who was murdered in Treblinka in 1942.

In her poem "The Little Smuggler," she relates to the hardships and dangers that young children had to endure in order to obtain food for their families.

The following poem is formatted to be read aloud by two students ("A" and "B").

The Little Smuggler / Henryka Lazawart

A: Past walls, past guards

Through holes, ruins, wires, fences

Impudent, hungry, obstinate

I slip by, I run like a cat

At noon, at night, at dawn

In foul weather, a blizzard, the heat of the sun

A hundred times I risk my life

I risk my childish neck.

B: Under my arm a sack-cloth bag

On my back a torn rag

My young feet are nimble

In my heart constant fear

But all must be endured

All must be borne

So that you, ladies and gentlemen,

May have your fill of bread tomorrow.

A: Through walls, through holes, through brick

At night, at dawn, by day

Daring hungry, cunning

I move silently like a shade

If suddenly the hand of fate

Reaches me at this game

'Twill be the usual trap life sets.

B: You, Mother

Don't wait for me any longer

I won't come back to you

My voice won't reach that far

Dust of the street will cover

The lost child's fate.

Only one grim question

The still face asks –

Mummy, who will bring you bread tomorrow?

Narrator:

From the poem we are provided a window into the upside-down world of the ghetto in which children like the little smuggler were taking care of their parents. It becomes clear that in addition to parents being the providers for the children, sometimes Jewish children had to become providers for their parents and family.

Eliezer recounted how his mother sacrificed her own needs for those of her children. He also tells us how he was able to retain his dignity by helping his family using money he earned while working.

Eliezer:

"Living in the ghetto, Jews lived on rations. You were given half a loaf of bread for 5 people... I remember we were all sitting together and when my Dad divided this half load of bread among 5 people, cutting pieces of bread so that everyone would have more or less the same portion, my mother always took a part of her bread and gave it to me... 'I'm not hungry,' she used to say and gave it to me. This I will always remember. In every way, whenever she could give up on her own needs for me... I knew she was sacrificing a lot... I had a lot of optimism, a lot of belief and a lot of hope and maybe I took this from my mother. I also used a lot of imagination. I said to myself that there will still be good times for the Jews when everything will come to an end. But what inspired me most (that I have) to continue to live and believe, was when I got this job working outside the ghetto... we were paid some money and with this, I could buy some food and bring it back to my family by smuggling it into the ghetto. That was also some of the inspiration that kept me going on and on..."

Narrator:

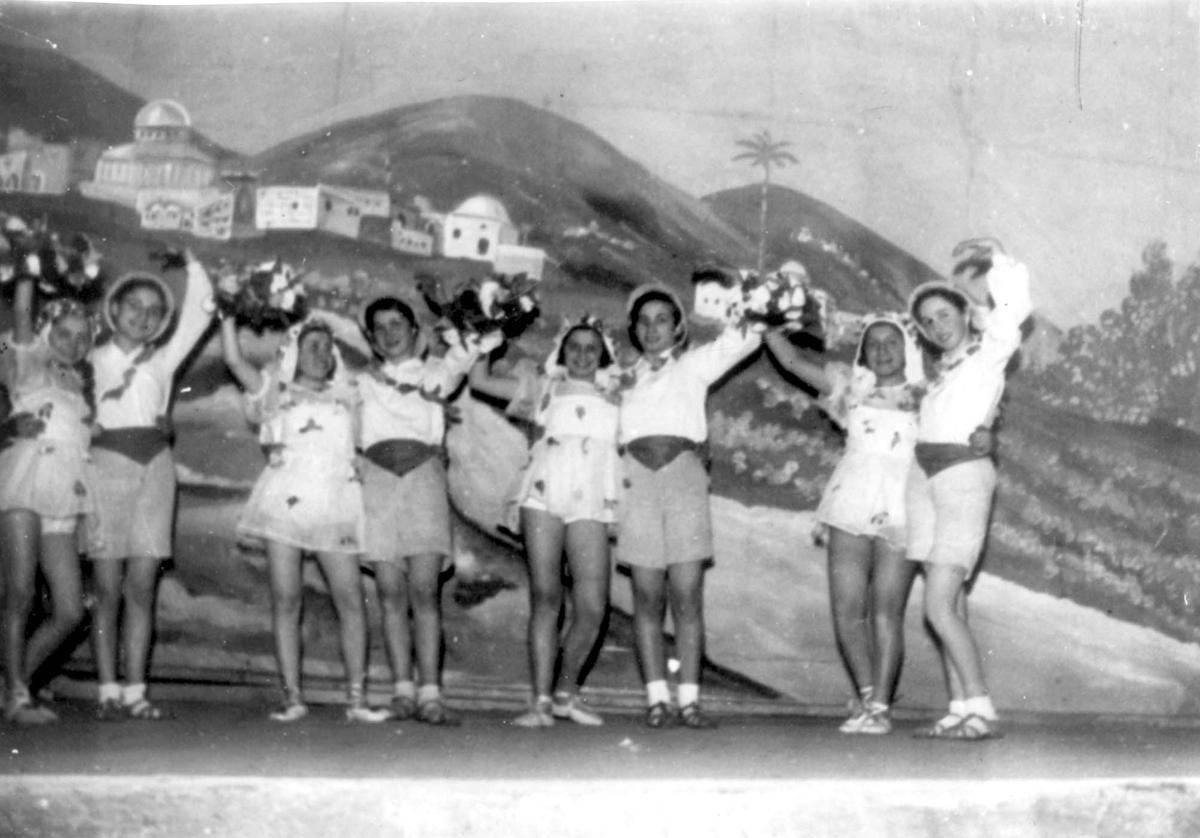

In order to maintain the feeling of normality in the ghetto, Jews worked tirelessly to organize schools, hospitals, religious gatherings, soup kitchens, and concerts, even though the Nazis had made all of these illegal.

The following testimonies, written by two Jewish girls, describe the spirit that prevailed despite being trapped within ghetto walls.

Sima, age 17:

"I remember the meetings of our youth club. In a broken old flat in a small street we met together... teachers, actors, singers, friends... for a couple of hours when we could. These meetings gave us the strength to go on. For a few hours we escaped from the terrible reality of our lives and found nourishment for our spirits. In the midst of terrible killings... not knowing if we would live another day... we tried to go on living... A choir was formed to sing Yiddish songs, and a drama circle performed plays. Contests were held for the best story... the best plays, the best song. Writers lectured for us. Poets read their poetry."

Mary Berg:

"From time to time we go to the theater. Last Sunday we attended a matinee concert... At her first concert, which Romek and I attended, the enormous hall of the Femina was packed full. She sang a group of songs. It was a pleasure to see her standing in the middle of the stage beside her father, who directed a twenty-man orchestra. The hall resounded with enthusiastic applause and she had to repeat several numbers. After the concert she was presented with three or four bouquets of magnificent flowers that had probably been smuggled in from the 'Aryan' side, because in the flower shops on Leszno Street roses and lilies are unobtainable."

Narrator:

Avraham Koplowicz, who suffered in the Lodz Ghetto, found his own way of escaping the harsh reality imposed by the Germans.

He dreamed. Through magical poetry, he was able to dream of escaping. One of his poems, 'A Dream,' describes a freedom that he never attained. Avraham Koplowicz was murdered in Auschwitz-Birkenau in September, 1944.

The following poem should be read aloud by a student.

A Dream / Avraham Koplowicz

When I grow up and reach the age of 20,

I'll set out to see the enchanting world

I'll take a seat in a bird with a motor.

I'll rise and soar into space

I'll fly, sail, hover,

Over the lovely faraway world,

I'll soar over rivers and oceans

Skyward shall I ascend and blossom,

A cloud my sister, the wind my brother.

(...)

I'll see the Pyramids and the Sphinx,

I'll fly over Niagra Falls,

I'll drift over the cloud strewn cliffs of Tibet,

By wind i'll cross the great kangaroo island

I'll fly slowly, hovering lazily,

And thus, basking in the enchantment of this world,

Skyward shall I soar and blossom,

A cloud my sister, the wind my brother.

Narrator:

Another aspect of survival was to have the love of a friend, when all else was lost. Many young Jews found themselves alone, without close family, brothers, sisters, parents, uncles, and aunts. They lacked companions of their own age to talk to about the happy lives that they had led before the Holocaust. Asher Ud, who lives in Jerusalem, spent the difficult years being moved like an object from ghetto to a work location, to a concentration camp, and finally, to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He describes himself as a simple solitary stone. He never enjoyed the advantages of a friendship like Eliezer Ayalon had with another boy his own age.

Eliezer:

"What I really missed was friends – you know, I was one of the youngest in the camp. There were not too many kids of my age. I was missing really a friend with whom I could speak and share a little bit of memories. Only later on in 1944 I met one of these friends of mine... Shlomo... The inspiration we got from one another helped us a lot... we used to encourage each other – the fact that we shared stories from the past – this was a great comfort. He was from Hungary and we spoke together in Yiddish. He was almost my age and it helped me a lot to be with a friend who could share things that I couldn't share with other friends – sort of family and friends – we shared everything..."

Narrator:

Masha Greenbaum, who grew up in Lithuania and now lives in Jerusalem, remembers her grandmother helping others in the ghetto.

Masha:

"My grandmother used to cook for people and she didn't even know them. They said to her, 'This family has just come in from somewhere in Germany and they have absolutely nothing.' And so she made for them a huge pot of soup. And I didn't understand so I asked her, Bobba Ettele, 'You are eating all this soup alone?' and she said, 'No my child, its for other people,' and she told me something else. She said, 'When they come in to eat don't stay there and look. It will shame them. Go away, go to another room.' And she told me, and I told my children... We have to think of not shaming people."

Narrator:

On May 8, 1945, the Germans surrendered to the Allies. It was only after that date that people began to understand what happened to nearly two million children in the camps.

Those who had been incarcerated in camps were barely alive when liberated.

After being in the ghetto, Eliezer Ayalon went through five camps. Once he became a number he was dehumanized and wondered how to restore his human image after so many years. He recollects:

Eliezer:

"Liberation to me was to bring back the image of humanity. The human image that was robbed – taken away. The moment I got this number I was dehumanized – I felt dehumanized but to bring back this human image was very difficult so what I was thinking when I was already satisfied and didn't need food was to search for a tooth brush, underwear, pair of socks, shoes – first of all I got rid of that uniform with the numbers and wanted to feel that I am back again to human life. This was a very long process. To take away the image of humanity was just like – well in a second, but to bring it back was very difficult – took some time – and eventually I returned to life..."

Narrator:

We conclude with the poem "Each of Us Has a Name," by the poetess Zelda.

The following poem should be read aloud by a student.

Each of Us Has a Name / Zelda

Each of us has a name

given by God

and given by our parents

Each of us has a name

given by our stature and our smile

and given by what we wear

Each of us has a name

given by the mountains

and given by our walls

Each of us has a name

given by the stars

and given by our neighbors

Each of us has a name

given by our sins

and given by our longing

Each of us has a name

given by our enemies

and given by our love

Each of us has a name

given by our celebrations

and given by our work

Each of us has a name

given by the seasons

and given by our blindness

Each of us has a name

given by the sea

and given by

our death.