Materials and Instructions

We suggest a student or teacher act as the narrator while several students take turns to read the various extracts of historical background and quotes from the two survivors. We recommend that a piece of music be chosen for one or two of the students to perform at the beginning of the ceremony, or for a song to be sung by the school choir. Relevant poems can also be read; for example, writings by Primo Levi, a survivor from Italy, may be added.

The Ceremony

Narrator:

Between 1939 and 1945, the Nazis and their collaborators murdered six million Jews, including one-and-a-half million children who were killed simply because they were Jewish.

In January, 1933, approximately five hundred thousand Jews lived in Germany. As a result of the rise of antisemitic persecution between 1933 and 1939, more than two hundred and fifty thousand German Jews left Germany for other countries. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 became the legal basis for the racist anti-Jewish policy in Germany. People with three or four Jewish grandparents were considered full-blooded Jews and persecuted.

Student:

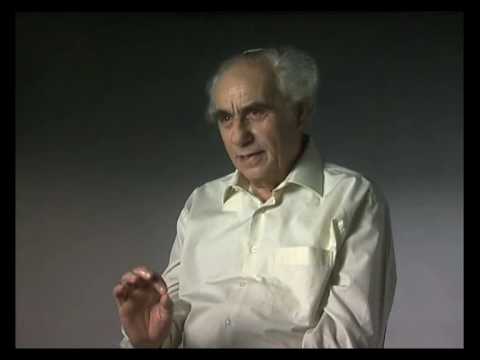

Professor Walter Zwi Bacharach was born in 1928 in Hanau, Germany.

Zwi, his mother, father, and brother, lived comfortably before Hitler came to power. They observed Jewish tradition but also felt proud to be German citizens. Zwi's mother enjoyed German poetry and songs, quoting often from Heinrich Heine and Johann von Goethe. His father had served in the German Army in World War I, and worked in banking and commerce. They felt both German and Jewish. He recalls:

"My family was not strictly religious but was traditional – we kept Shabbat and Jewish holidays. Until 1933 I don't remember having an abnormal childhood. At that time I had many German friends, until the Nazi times. My parents had many German friends, also. Some German Jews were well-to-do and assimilated. My mother was totally embedded in German culture – she felt German and Jewish as well, being aware of her Jewish identity and that we were Jews, but we were assimilated. My father fought as a soldier in World War I and received medals in recognition of his participation. We were a typically German-Jewish family – aware of our Jewishness, but thinking German."

Narrator:

On November 9-10, 1938 many Jewish homes, businesses, and synagogues were looted and burned in what was to become known as Kristallnacht ("Crystal Night" or "Night of the Broken Glass"). This was a pogrom (massacre or riot against Jews) carried out by the Nazis throughout Germany and Austria. Approximately thirty thousand Jews, many of them wealthy and prominent members of their communities, were arrested and deported to the concentration camps at Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald, where they were subjected to inhumane and brutal treatment resulting in many deaths. During the rioting itself, some 90 Jews were murdered. After Kristallnacht, many German Jews who had not already left, heeding the drastic changes and unpleasant atmosphere for German Jewry, decided to escape, but those remaining at the outbreak of war in September 1939 found it increasingly difficult to leave; daily life became intolerable and threatening.

Student:

Zwi remembers, "I attended elementary school in Hamburg and we stayed there until Kristallnacht which was in 1938. My parents, like many other people, didn't understand what was going on. My brother and I were attending a Jewish school in Hamburg, and when we went home every day we were beaten up by the Hitler Youth who came out of the non-Jewish school next to our school, and we came home wounded. Eventually, my parents, brother, and I succeeded to get out to Holland, where we lived until 1942, when the Nazis caught us."

Narrator:

As a child living in The Netherlands, Zwi was forced to wear a yellow star on his clothing. He describes his feelings as he wore this branding mark.

Student:

"I wouldn't even say it was insulting – it was embarrassing, because everyone would turn around and stare at you. I always compare this feeling to when I had my bar mitzvah and I had to wear a big hat to synagogue. When I wore the hat everyone stared, and it was the same with the star. I felt I was being isolated; you're being pointed at. It was an awful feeling, but couldn't be compared with what would come later."

Narrator:

Italian Jews were totally integrated in the life of the country and felt profoundly patriotic. Many of them belonged to the middle class. In September, 1938 Mussolini initiated anti-Jewish legislation that caused both material and emotional suffering to Jews in Italy. They were banned from the educational system and from their places of employment. Relationships with non-Jews were forbidden. They could no longer belong to any non-Jewish organization or association. They could not join the army nor participate in any non-Jewish social activities. Their property and assets were often confiscated.

Student:

Chana Weiss grew up in the beautiful port city of Fiume, Italy. She was a member of the Jewish community consisting of some two thousand, many of whom, like Chana's father were immigrants from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. Chana and her family were thoroughly integrated members of their community, both as Jewish and loyal Italians, and spoke several languages, including Hungarian, German, and Italian – reflecting the international flavor of the city.

Chana, her brother, and two sisters had a happy childhood until 1938 when anti-Jewish racial laws were introduced in Italy.

Chana remembers, "I was the only Jewish child in my class and I never felt uncomfortable. The only antisemitic episode I remember is when I was walking on the street with my Catholic nanny. A young boy from the poor part of the city approached us, and when he passed by he called me 'chifuti' – Jew. The Christian woman who was by my side said to him 'Do you know who Jesus was? Jesus was a Jew – so enough with the 'chifuti.' I was even in a fascist youth movement – until 1938 when I was thrown out."

Narrator:

After the anti-Jewish laws were passed in 1938, many citizens were forced to emigrate from the country. As Fiume only became part of Italy after World War I, this law had terrible consequences for many Jews living there, who suddenly lost their Italian citizenship and were considered alien residents.

Student:

Chana recalls, "The expulsions began. The Jews from Hungary received expulsion orders, and were forced to return to Hungary. I remember we were very close to our neighbors; I always played with their children, who were my good friends."

Narrator:

The fate of Jews under Nazi rule deteriorated dramatically in the following years and reached the Nazi decision to systematically murder all Jews. By November, 1941, extermination camps in Chelmno and Belzec were already being built with facilities for murder by poison. Zwi Bacharach's family, having fled from Germany to The Netherlands, was now forced into a transit camp, a ghetto, and finally an extermination camp. The nightmare of the Holocaust unfolded for them in its various cruel forms.

Student:

Zwi recalls, "January 29, 1942, the Gestapo was in our house. I remember this distinctly because I was lying sick at home with a high fever and the Gestapo gave us, and I remember this well, not 5, not 10, but 8 minutes to get out of the house and to the station."

Narrator:

Zwi and his family were sent to Westerbork, a transit camp through which most Dutch Jews passed on their way to Nazi extermination camps in Eastern Europe.

A year later, the family was sent to the Theresienstadt Ghetto, where even though life was very difficult they were at least housed together, but even this ended abruptly.

Zwi states, "...on Yom Kippur, 1943, my brother and I were on the street, and they picked us up. They put us in the back of a truck and we were taken to the wagons waiting to transport us. My father didn't see us, he was at work, and I saw my mother, but she didn't see us. It was the last time I saw her alive."

After the Germans invaded Italy, and after the establishment of the Fascist Salò Republic, the situation for Jews further deteriorated. Jews began to be deported to the death camps by both Nazi Germans and Fascist Italians. All Jewish property was systematically confiscated. Chana, her mother, two sisters, and grandparents tried to escape to Switzerland, but were caught and interned in the San Vittore prison. Later they were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, in Poland, the largest of the Nazi extermination camps.

Zwi and his brother were also deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Both Chana Weiss and Zwi Bacharach describe how the Nazis and their collaborators degraded them on the transports to the East.

Student:

Zwi remembers, "Westerbork and Theresienstadt were insulting and humiliating, but the dehumanizing began the moment we climbed into those cattle cars. We were treated like cattle. One hundred and fifty people were in one cattle car. Not being able even to sit down. We were two days and two nights in the wagon and this was my first confrontation with death – there were dead people in the wagon."

Chana notes, "We were put into a cattle car. The inside was huge and there was nothing in it, apart from a bucket, or container. People climbed up into the cattle car, first of all the elderly, who immediately sat with their backs leaning against the walls. There was hardly any room. 80 people were crammed into my car."

"There were four small openings, like windows, but we could only look out of one of them. The others had some kind of bars over them."

"I mainly remember great hunger and thirst, as there was no water to drink."

Narrator:

Upon arriving at Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp, Zwi and Chana recall the horrors they witnessed.

Student:

Chana: "The first thing I saw, as they opened the door of the cattle car on arrival in Birkenau, was a prisoner in striped clothes, shouting in German 'QUICKLY QUICKLY QUICKLY, everyone down!' He wasn't the only one shouting. One hundred men dressed like him were shouting at the same time, along the entire length of the platform. Added to this was the barking of the SS dogs... the noise was simply terrible."

"All we wanted to do was to get down, so they would stop the awful noise. We were confused, dirty, exhausted, and starving. Where were we? I didn't know. We just wanted to get out of the cattle cars. I was suddenly alone – I looked for my family, my family looked for me. So it was all one huge shout. It hurt our ears and it definitely didn't help the terrible mental or physical state we were in..."

Narrator:

The next stage that Chana describes was the final separation. Infamously known as "Selection," it was here that an SS officer with the small movement of a finger would decide who would be killed instantly and who was destined for slave labor.

Chana describes it thus.

Student:

"Suddenly I found myself in front of a German officer... he was big, fat, and elegant... I stood before him. He didn't speak. He looked at me, and raised his fist, and stuck his thumb upwards. I understood from this that I was to go to the right. I looked up and through the barbed wire, saw a few figures standing there. I understood that I should join them; as I went towards them I turned around and saw my elder sister behind me. I asked my elder sister, 'Where are Mama, Magda, and Grandma?'"

Narrator:

Upon arrival at the camp itself, Chana was taken to a small room, or office, where two women awaited her.

Student:

Chana: "I didn't feel the second girl taking my arm, and pricking me with a needle. She had tattooed perhaps two numbers when I noticed what was going on. I started shouting, 'What are you doing to me?'"

"She then explained to me that from this day forth, I had to memorize this number in German, and remember it even if I was wakened during the night. Also to learn the number to hear it called, and also to say it myself aloud... my name Chana, or whoever I once was, was now erased."

"She finished with me, and I was sent to another very small room, to sit on a chair. Someone took my hair, lifted it up, and within 2 minutes, I was bald. Then they took me to a third room, where a girl told me to 'get undressed'."

"I looked at her. What do you mean, get undressed? I'd never undressed in front of anyone in my life, except myself in the shower, and even then I would turn the key twice to lock the door."

"In the end I was sent out of the room, naked, bald, and numbered to join the other women like me sitting shocked in a big hall..."

Narrator:

Zwi also recalls his arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Student:

"We got off the train like cattle and the women were separated from the transport. One of the men helping us down off the cattle car told me to say I was eighteen. I was actually fifteen. We had to undress and were given the striped uniform and wooden clogs which hurt our feet. Everything was done in a rush. Our transport was destined to be sent to Germany for forced labor, which was our luck, so I wasn't tattooed with a number."

Narrator:

Zwi continues with a description of the day-to-day deprivation and the effect of accumulating suffering of the prisoners.

Student:

"Once a day we were given a dish of watery soup to share between five people. So I always say that the greatest pain, besides the longing for parents, was the pain of hunger. For youngsters you don't have a solution, only hunger. Hunger was on our minds the whole time. Sometimes we got a piece of bread to share between five people. There was always a fight for a piece of the bread, and we youngest always lost – we were not strong enough. I don't know how I survived. We only existed there, and many died. In the morning, in the cold, almost frozen to death, we stood for roll call. I don't know how or why but we continued to live. It was absolute torture."

Narrator:

Both Zwi and his brother, and Chana and her sister, managed to survive the Holocaust. Most of their family members, however, were not so lucky.

Chana's mother, sister, and grandparents were killed in the gas chambers within hours of their arrival.

Zwi's father was briefly interned with his two sons. He told them of their mother's death on the transport, and after that never uttered another word.

They were taken to a camp near Leipzig called Tolcha and worked eighteen hours a day in a munitions factory, under terrible conditions.

In March, 1945, as the Allies approached and the Nazis realized they were losing the war, the prisoners including Zwi, his brother, and their father, were sent on a death march. During the march, Zwi's father was shot and killed by the Nazis in front of his sons. Zwi and his brother survived the death march and were eventually liberated by a group of American soldiers.

After the war, Chana returned to Italy and was reunited with her father. She studied nursing and eventually moved to Israel. She married a Jewish-Hungarian survivor of the Holocaust and together they had three children.

Zwi made the decision to move to Israel. After completing his formal education, he became a history teacher and later an historian and university professor. He and his wife have three children and many grandchildren.

The private reminiscences of Zwi and Chana that we have just heard are part of a large collective bank of memory of the people who lived through the Holocaust. We are indebted to Zwi and to Chana and all those who have provided us with the painful recollection of their ordeals, so that the future telling of the Holocaust will be ensured for generations to come.