Materials and Instructions

Materials needed for this ceremony: copies of passages to be read aloud (those below), distributed by the facilitator to the students. We recommend choosing two narrators and eight readers. The narrators will read all explanatory texts, whereas the readers will give voice to pieces of certain women's testimonies. Appropriate music for the ceremony, such as classical compositions, can help create a suitable atmosphere.

The Ceremony

Reader 1:

Olga Lengyel, a survivor of Auschwitz and Birkenau, expressed her torment, "I am a woman who suffered, lost her husband, parents, children, and friends."

Narrator 1:

"And to them will I give in my house and within my walls a memorial... an everlasting name [a 'yad vashem'], that shall not be cut off."

Narrator 2:

Women and men had different experiences during the Holocaust. This ceremony focuses on the difficult situation of women in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

Narrator 1:

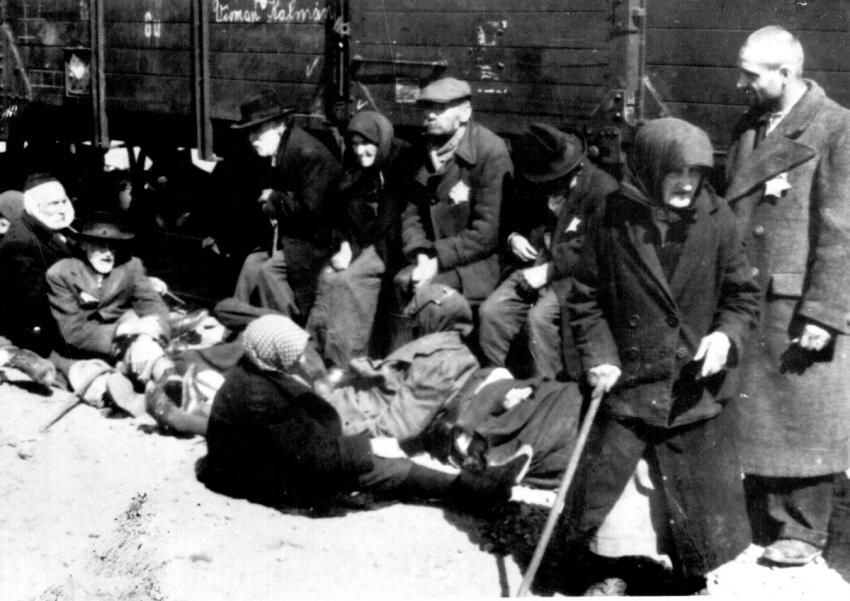

The journey to and arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau was, in most cases, the last stage when husbands and wives, parents and children, brothers and sisters were together. In her testimony given to Yad Vashem, Betty Perkal describes her arrival at Auschwitz.

Reader 2:

"Whoever tried to describe that didn't describe anything. I don't know who can. This is, it was the end of the world. It is unbelievable. The inferno of Dante, that's a pale description. It was hazy, very hazy. The trains arrived on a platform. It was drizzling. [...] Everybody was screaming. There was a noise which was unbelievable. [...] The Germans. They were saying, 'Schneller, Schneller, Schneller.' But kids were crying. People were crying. I heard noises. I got deaf. At some stage, I heard myself screaming. I didn't know what happened to myself. I screamed like... I don't know why, what. It came from you, like unconscious and everybody was screaming. Somebody was saying something because people were also calling names, trying to stay together. I didn't find anyone. I didn't see my mother nor my father, anyone. And we were kicked and kicked and we were running, just running."

Narrator 2:

Lea Kahana-Grunwald recounts:

Reader 3:

"No mother anymore. No mother with me. Mengele separated us. No mother, no little sister. The three of us from the family, the three sisters. When we looked there after the selection, we saw my brother. That's who came to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Not the father, not the little brother and not the little sister."

Narrator 1:

On their arrival at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, men and women were divided into two separate lines. As they stood there, the selection began.

In her testimony, Laura Varon, a Jewish woman from Salonika, Greece, describes the selection process, and the "choiceless choices" that she and her sister had to face.

Reader 4:

"They opened the doors, the squeaking doors... and a little bit of air came... When we arrived in Auschwitz, we were already numb: the bones, the legs were not moving anymore. Two men in striped uniforms, because they heard us speaking Ladino, they told us in Ladino, 'We are Greeks from Saloniki. Give the children to the old people,' they told us. Again, we didn't [understand] what this meant. How can you understand, 'Give the children to the old people?' And then they were afraid to talk to us and that's all, 'Give the children to the old people.'"

Narrator 2:

Feige Serl-Lax faced the same dilemma. Alone in the horrible chaos of Auschwitz, she and her sister had to decide what to do with her sister's young children.

Reader 5:

"...And then we were in Auschwitz and then they opened the door, the Polish Jewish boys come... They were there... a long time. And he sees my sister, [she] was a beauty. He said, 'You have children?' She said, 'Yes. Two children.' And in that manner he said, 'Let the children go left and you two go right.' I take out the child and my sister takes out [the other child] and we don't let him. We come in the line to Mengele. That Polish man that I didn't want to release the child to, then he comes and takes the child from me and pushes me to the right... and he wants to take from my sister, also the little boy... Mengele was angry and told my sister to go left. I never [saw] her again. That was the last time."

Narrator 1:

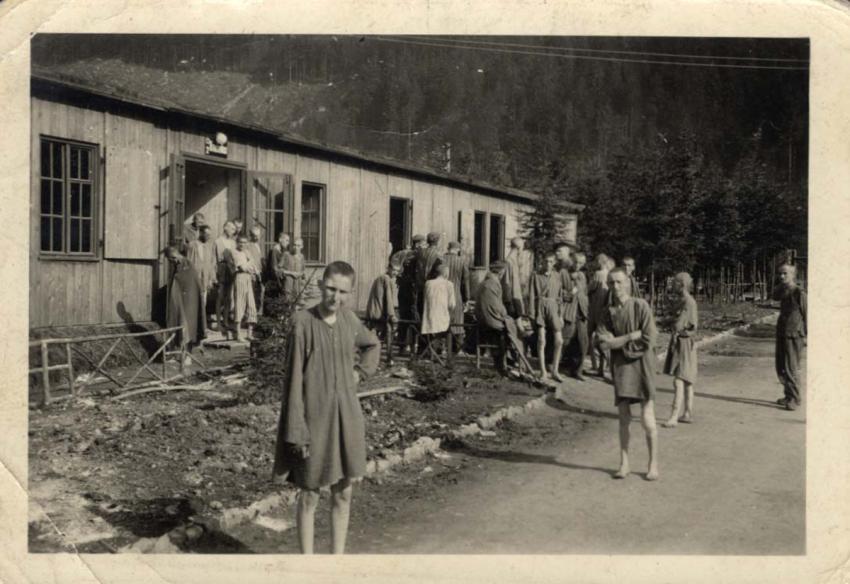

The "Sauna" was the first stage of the de-humanization period, where newcomers began the registration process. They were stripped of their clothes and made to feel like a number instead of a human being. They were showered, disinfected, shaved, tattooed, and given a prisoner uniform and wooden clogs.

In her testimony, Tova Berger talks about the humiliation and shame that she felt during her passage through the "Sauna."

Reader 6:

"...They told us to get undressed and they shaved us. They shaved my beautiful blonde hair and my two sisters' hair and we were standing naked before the soldiers and for me it was a shock because I was a religious girl. I never was undressed in front of a man and they made all kind[s] of dirty jokes about our bodies and they looked at us and I was standing there shivering, naked, without hair on my body, and I was exposed. I felt like an animal... and the way they treated us already there was so terrible, then I said, "Where is G-d? Where is G-d?..."

Narrator 1:

Yehudit Rubinstein shares her horrific experience.

Reader 7:

"...They sent us... to the bathhouse. So there the first order we got: Everything off. We just couldn't believe what [we heard]: to take off everything, take off clothes, everything, pins from your hair, everything out. We were uncomfortable, the first time in my life I was in public, undressing in front of men, coming in and out, then we understood that nothing will help us, so we had to undress, and they called 'Who is a hairdresser?' ...So one woman whom I knew as a young girl from my town, she was a hairdresser, so step by step with the scissors and with their machine started to cut the hair, other parts, everywhere, private parts, before we turned around under the shower, opened the water before we had a chance to wet ourselves: 'Raus' [Out], they gave us this gray uniform, and just our shoes – the lot of us were holding on to their shoes, put on their shoes, bare naked and nothing on them and out in the garden, out in front of the bathhouse."

Reader 1:

"The camp was no maternity ward. It was only the antechamber to hell."

Narrator 2:

What happened to women who arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau pregnant? Some women were able to hide their pregnancies when they entered the camp. Later, when they gave birth, they were faced with a terrible choice: either they could kill their newborn infant and ensure their own survival, or sentence both themselves and their child to death.

Lea Kahana-Grunwald recalled:

Reader 3:

"A girl came in. She came in with her mother. She was pregnant and he overlooked it, Mengele. He didn't notice. It was a young girl, a young person. The first child. She wasn't so big. She had [the] child on the "pritsche" [bunk], without any help. The mother was with her and I suppose the staff helped her through it... I don't know what they did with the child, whether they burned it or what. She gave birth and she had to stand next morning at 'Zaehlappel' [roll call]. She survived. The child was killed. How they killed it I don't know the details, but I knew the girl. She was from my town and she got married a few months earlier. That was her first pregnancy, her first child."

Narrator 1:

Judith (Yehudit) Rubinstein describes in her testimony how another woman planned to kill her baby by giving it aspirin, a drug not intended for such small babies.

Reader 7:

"...One woman gave birth to a baby overnight and she was running after us, she knew that we are going out to Brzezinka, begged us that we should bring her aspirin, she wants to give it to her baby, because if Mengele will find her with the baby... that's the end of her. A beautiful young woman. And she cried and begged us, and maybe her husband will make it, maybe she will survive, she can have another baby, but if they will kill her, that's the end of a whole generation. So we were the whole day tortured, a friend and myself, the two of us, what should we do. Should we bring the aspirin, should we... We brought the aspirin we gave it to her, but I could never look at her. I felt so guilty, but... circumstances were – I felt like I killed that baby, but there was no way."

Narrator 1:

After the war, survivors were in shock. They had lived through horrifying experiences and were left alone in the world. Many did not know for many years what happened to their families.

Reader 3:

"We wanted to look at what had happened, where we were. So first of all, we don't dare to speak, even those who were there already a longer time, like our 'Blockaelteste' or the 'Schreiberin' or the 'Stubeaelteste' who were in control. [...] We asked what happened to our mothers and to the ones not with us. 'We got them,' they said. 'The day you arrived to Auschwitz, whoever will remain alive should know that as your 'yahrzeit,' your 'yom zikaron' [memorial day]. After those who are not here, this is the date... We learned what happened, I don't need to tell you how we felt."

Narrator 2:

Betty Parkal expresses her complete loss after learning that she is all alone.

Reader 2:

"After these days, I probably got the message... [my parents] are gone. It was useless. We didn't look at people who were not there. There was no way my mother could have been [...] with us. I assumed my father was also gassed immediately because I didn't hear... I asked several people. Men, if I could talk to them and ask them if they met. But we knew. We knew because we were living that. My father was then 44 or 45 years old. This was old for Auschwitz condition[s]. Not a good strong man. A fearful man. A man who had been beaten. He didn't stand a chance to get into the camp. I accepted that immediately."

Narrator 2:

The Holocaust left an indelible mark on the survivors. The trauma experienced by those who were subjected to the Nazi regime was so great that it remained with them and continued to accompany them throughout their lives. In many cases, it was also passed on to the second and third generations. Despite the remarkable return of these survivors, who established new families and returned to life after the war, the pain of losing family members never left them, even after they managed to build new lives and a future generation.

Narrator 1:

Miriam Buki talks about life after Auschwitz.

Reader 8:

"Life doesn't have the meaning, the joy that life had when we were young. [...] Now, it comes more. I still have dreams. They still shoot me and it still hurts. What I meant to say, we survived. We are survivors but we didn't survive the pain. We didn't survive what we went through. We didn't survive the misery."

Narrator 1:

We conclude with the words of Yehudit Rubinstein, who speaks about the importance of education in trying to prevent events like this from ever occurring again.

Reader 7:

"...I feel very strongly that we should warn and educate our youth; they should be aware... what could happen to people who are innocent and so little informed as we were, because antisemitism is always somewhere and we have to be on guard and this is the only thing, is education."