The film we will discuss in this issue had its beginnings in France, when director Louis Malle was a young student at the Petit Collège des Carme, a Christian school in Avon (Seine-et-Marne). The principal of the school, Lucien Bunel, better known as “Father Jacques,” decided to accept persecuted Jewish students at the school. Father Jacques accepted three Jewish students: Jacques Halpern, Maurice Schlosser, and Hans Helmut Michel. The three boys lived and studied at the school under false identities and names given to them by Bunel. Bunel also employed Lucien Weil, a teacher of natural sciences who had been dismissed from his previous job following the Vichy regime’s restrictions on the employment of Jews. On 15 January 1944, after informers provided precise information about the Jewish students, Gestapo police arrived at the school gates and arrested the three Jewish students and Father Jacques; Lucien Weil and his family were arrested later the same day. The three Jewish students and Weil and his family were sent to Auschwitz, where they perished. The school was closed on the orders of the Germans, and Father Jacques was deported to Mauthausen. He managed to survive until the liberation but, exhausted by the inhuman conditions of his imprisonment, he succumbed several days later. His body was returned to France and buried in the cemetery of Avon.

Since Bunel’s Jewish protégés perished, the testimony about Father Jacques’ attempt to save them was given by Hans Helmut’s sister. She added that during the school vacations he arranged a meeting between her and her brother. She expressed her gratitude to Father Jacques and explained that she did not how and when she could pay the school tuition. Father Jacques replied that he expected nothing in return; on the contrary, he would be pleased to see her brother continue his studies, and since the boy had no parents, Bunel would gladly take their place. On January 17, 1985, Yad Vashem recognized Lucien Bunel, also known as Father Jacques, as a Righteous Among the Nations.

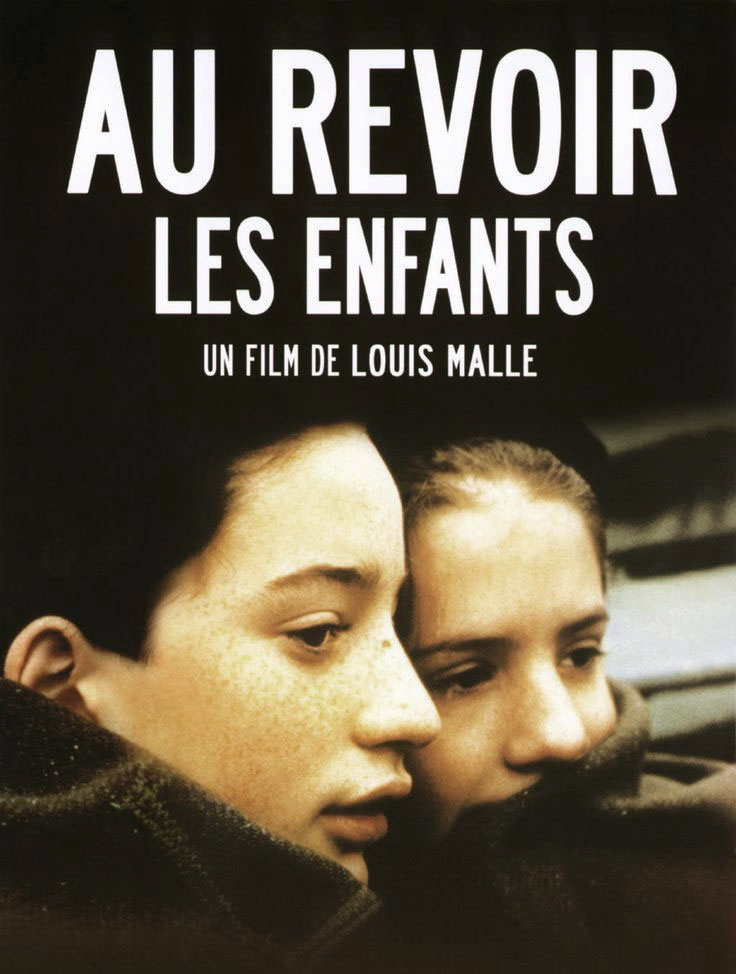

Louis Malle, who was a student at the school himself and witnessed the rescue story, wrote and directed the film Au revoir les enfants in 1987. The film was extremely successful and

won several prominent film awards. The film’s script was published in book form that same year. The plot of the film is based on authentic events from Louis Malle’s youth.

A new student arrives in the class of the film’s hero, Julien Quentin, a character who is possibly based on Malle himself. The new student, Jean Bonnet, turns out to be particularly gifted in mathematics, writing, and piano studies. Quentin had until then considered himself the most outstanding of his peers and became jealous. The two boys are suspicious of one another and occasionally hostile. However, the intimate family atmosphere at the school eventually turns the relationship between the two boys into a deep friendship.

Quentin is curious about the new student, who unlike his peers does not attend prayers or eat the pork served at lunch. This leads him to discover Jean’s secret. However, thanks to the friendship between the two, Quentin remains loyal to his friend and does not reveal the fact that he is Jewish. Quentin’s concern for Bonnet’s wellbeing ostensibly leads him to be seized by the Gestapo, although in reality the reason was clearly the precise information provided about the Jewish students attending the school.

“Au revoir les enfants” is a fascinating catalog featuring characters who shared similar experiences yet who made completely different choices. The film portrays the “free” France of the Vichy regime under Marshal Pétain, depicting the different sections of French society and their responses to the collaboration and the German presence in France. The students’ political discussions, which also reflect their parents’ positions, cast light on the attitude to the regime that collaborated with the Nazis – an attitude that ranged from support to suspicion to hatred and opposition to Nazism and collaboration.

It is interesting to study and contrast two characters: the rescuer Father Jacques and Joseph, who at the end of the film becomes a collaborator.

Father Jacques agrees to take in Jewish students at the school, perhaps driven by religious Christian motives of mercy and compassion for the persecuted. It is important to recognize that the effort to keep the identity of Bonnet and the other Jewish students a secret demanded that several members of the teaching staff share the secret. They also took the risk that the rescue attempt would be discovered and that they would be punished by the Germans. Many of the parents regarded Father Jacques’ holiday sermon to the children and parents as excessively hostile and critical. The speech struck at the soft underbelly of French bourgeois society, which Jacques believed accepted reality and abandoned the believers’ fundamental beliefs:

“My children, we are living in an age of strife and hatred. The lie is at full strength. Christians are killing each other, and those who are supposed to guide our way are betraying us. More than ever, we must beware of selfishness and apathy.

You all come from wealthy families, in some cases very wealthy. Since you have been given a lot, you will also be asked to give a lot […] Material wealth corrupts the souls and dries up the hearts. It makes people scornful, lacking in their sense of justice and merciless in their selfishness. I well understand the rage of those who have nothing while the rich arrogantly stuff themselves. […] Let us pray for all those in suffering, those who are hungry, those who are persecuted. Let us pray for the victims and also for the hangmen.”

The intermediate generation, between the priests and the young students, is represented by Joseph, a young lad who works in the kitchen at the school. The seventeen-year-old boy comes from the margins of society and is afflicted by a slight disability. He is unlikely to be drafted and does not appear to have completed school. Joseph is ostracized and mocked by most of the students. He deals with some of them on the local black market, selling the food items their parents send to them in return for stamps. Joseph’s nascent anti-Semitism is hinted at in an early scene during a commercial negotiation with Julien. When Julien proves to be a tough bargainer, Joseph hisses: “You’re a real Jew.

After the illegal trading is exposed, Joseph and the students involved are summoned to Father Jacques’ room. The priest always encourages the students to share the parcels they receive from their parents with their friends who do not receive them (including the Jewish students, whose parents have already been detained, imprisoned, and deported from France). He chastises them:

“For me, the true meaning of education is to properly use the freedom of choice you enjoy. And this is the outcome! You disgust me. There is nothing I find more repellent than the black market. Money, always money.”

Father Jacques cancels the students’ Easter vacation and dismisses Joseph. Malle hints that the priest regrets dismissing Joseph as he continues to observe him. His action turns out to have tragic consequences for the priest and his students. Joseph becomes a collaborator and provides the Gestapo with information about the rescue attempt. When the Gestapo raid the school, Jean Bonnet (Kippelstein), Dupre, Negus, and Father Jacques are arrested. The helpless Father Jacques turns to his students: “Au revoir les enfants.”

In his autobiography “Where Memory Leads," the historian and Holocaust researcher Shaul Friedlander describes his childhood in France during the Second World War. Friedlander’s family, who originally came from Czechoslovakia, migrated to France not long before it was also occupied by the Nazis. In an attempt to save their child, his parents decided to send him to a Christian residential school in the Vichy zone run by priests. The young boy was baptized and renamed Paul-Henri Marie Ferland. Friedlander was required to learn the Christian prayers quickly and become familiar with the Christian way of life in order to blend in with his surroundings without arousing the suspicion of the other students or staff members who were not party to the secret. The inherent duality of a false identity and the need to maneuver between different identities, or to erase any memory of the old self, is the foundation for the distress and tragedy experienced by those who were hidden or who lived under an assumed identity. Friedlander’s longing and concern for his parents during this period may help us understand what the character of Jean Bonnet and many other children hidden under false identity experienced. Friedlander described the process he was forced to undergo:

“The conversion of an adult may be a merely formal matter, and such cases were numerous during the war, or it may be the outcome of a spiritual development leading to a freely-made decision; nothing disappears, but everything changes shape. In this case, the new identity alters the previous existence, which is retrospectively regarded as a maturation or preparation. The denial of the past that was imposed on me was not merely formal – after all, my father had agreed not only to my conversion, but also to ensure that I would receive a Catholic education if life returned to its normal track. And it goes without saying that it was also not the outcome of a spiritual development. The first ten years of my life, my childhood memories, had to vanish since there could be no synthesis between what I was and what I had to be from this point forth.”

“In my own way, I totally denied my past: Although I was aware of my origins, I felt comfortable among those who felt nothing but scorn for the Jews, and I casually enflamed this scorn. I had the feeling – undefined yet clear – that I had moved over to the firm and invincible majority, and that I no longer belonged to the camp of the persecuted, but – at least potentially – to the camp of the persecutors. […] Paul Friedlander had vanished – Paul-Henri Ferland was a different person.”

Friedlander’s parents attempted to escape to Switzerland but were caught and deported to Auschwitz. After the war, as an orphan, he planned to continue with his church education. One of the priests who had been involved in educating him and who had a close relationship with him called him in for a conversation, reminding him of his Jewish past and of the fate of his perished parents. It is important to note that not all the clerics who helped to conceal Jewish children acted in this manner: some of them preferred that the children remain Christians rather than return them to Judaism.

“For the first time, I felt myself to be Jewish – this time not against my will or in secret, but through an impulse or full identification. Although I knew nothing about Judaism and I was still Catholic, something had changed, a connection had been recreated, an identity had emerged and arisen – certainly confused, perhaps contradictory, but from here on it connected to a central axis that could not be doubted: In some way or another, I am a Jew, whatever this concept might mean in my mind’s eye.

The priest’s attitude in itself influenced me profoundly: The excitement and respect as he spoke to me of the fate of the Jews certainly constituted an enormous encouragement. He did not push me to choose one way or the other – and he might perhaps have preferred me to remain a Catholic – but his sense of justice (or perhaps it was a profound fellowship) restored my right to judge for myself, by helping me to renew a connection with my past.”

The synthesis between “Au revoir les enfants” and the memoirs of Shaul Friedlander may cast light on the end of the film (when the children are handed over) and on the events that might have transpired had Father Jacques’ protégés survived. The two stories can perhaps serve as a foundation for an educational discussion on the issues they raise, including premature maturation, the relations between Jews and French people under Nazi occupation, local anti-Semitism, life with a double identity during the Holocaust, collaboration with the Nazis, and, of course, the rescue stories. We began our review with the true story of Lucien Bunel (Father Jacques) in order to anchor the film in its historical context; however, another possible message is that an attempted rescue should not be evaluated according to its outcome but according to its intentions. In other words, although it does not end with the survival of the persecuted, it still constitutes a human gesture of mercy, and sometimes even a personal and tragic act of sacrifice on the rescuer’s part.

Focus of Discussion

- What is Quentin’s initial attitude toward Bonnet? How does this attitude change over time?

- How does Quentin react when he discovers that his classmate is a Jew? Could we say that he has anti-Jewish prejudices?

- Bonnet says that he is afraid all the time. What difficulties did he face during his studies in a Christian school (discuss different aspects of his Jewish background, the uncertainty about his parents, and existential anxiety)?

- How would you describe the character of Father Jacques? Discuss different scenes (Quentin’s confession, the priest’s sermon in church, his capture by the Germans).

- Regarding the scene in which Quentin’s family sit in the restaurant with Bonnet, describe the different reactions when the militiamen come in and ‘expose’ the Jew.

- How would you describe Joseph’s character? Why do you think he collaborates with the Germans at the end of the film?

- Try to compare the characters of Father Jacques and Joseph. Discuss each one’s motives and behavior.