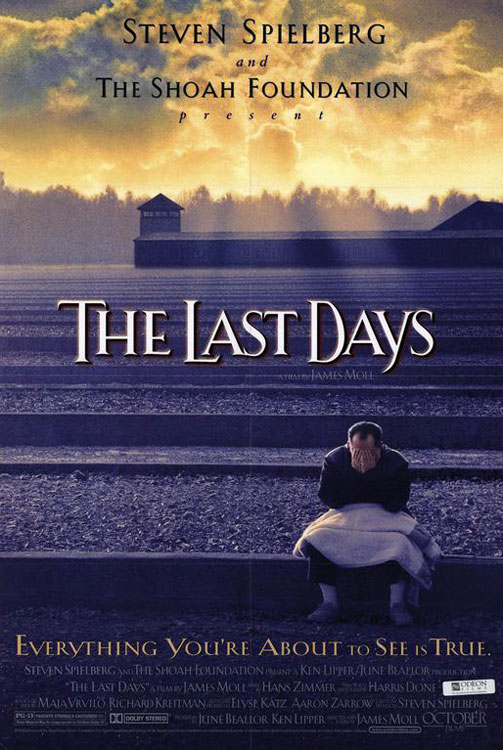

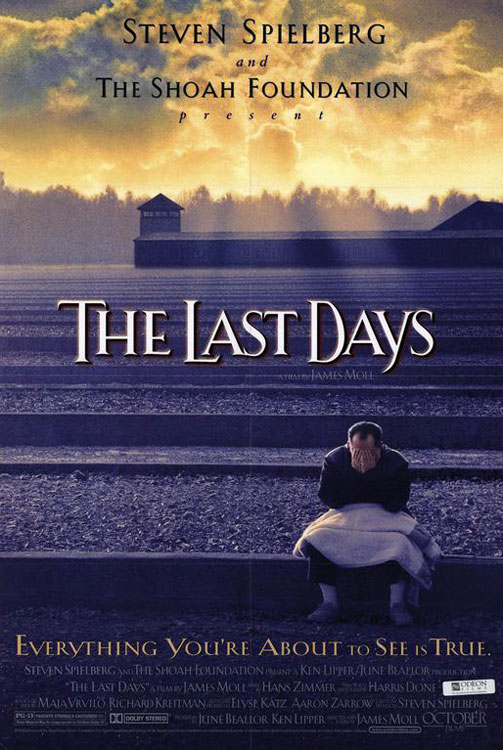

"The Last Days" - Movie Poster

Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

"The Last Days" - Movie Poster

"The Last Days"

Director: James Moll

USA, 1998/ English, German and Hungarian

87 minutes

Producers: Ken Lipper and June Beallor

Executive Producer: Steven Spielberg for the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation

Winner, Best Documentary Feature - 1998 Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

"There is one thing that has puzzled me and has puzzled the world: that the Germans dedicated manpower and trains and trucks and energy towards the destruction of the Jews to the last day. Had they stopped six months before the end of the war and dedicated that energy towards strengthening themselves, they may have carried on the war a little longer; but it was more important to them to kill the Jews than even winning the war."

These are the first words spoken in The Last Days, and they are spoken by Bill Basch, a Holocaust survivor from the town of Szaszovo, Hungary. That the movie begins this way reveals its focus. The film is not just another documentary about the Holocaust; it is a documentary about a specific period and a specific place during the Holocaust – a period of less than four months beginning in March, 1944 when the Nazis' genocidal fury was unleashed against the Jews of Hungary. Through the testimonies of five survivors of that last, intense period of the “Final Solution,” the uniqueness of the plight of the Hungarian Jews is brought into sharp focus. Additional testimonies add depth to the stories shared by these survivors. The movie presents an excellent synopsis of the Shoah in Hungary.

In addition to presenting the story of Hungary, though, the movie gives us a broader understanding of the Holocaust in general. As we know, the Holocaust happened across the length and breadth of Europe, and unfolded differently in different places. Yet there are many elements that were similar, if not identical, in each of these places. One of these elements is that wherever the Holocaust occurred, the Jews typically could not fathom that they were in a life-threatening situation, often until it was too late. At first, most Jews believed they would survive by working for the Germans. Speed, secrecy, and deception were purposely used by the Germans to carry out deportations and killings, and to impede Jewish knowledge of a new, murderous reality. Moreover, the Holocaust was a crime on such an unprecedented scale that common sense could not conceive of such a thing: genocide of the Jews did not make any sense; it was illogical. In addition, there was a need for hope, a need to believe that genocide could not happen here, "could not happen to me." All of these factors, and more, contributed to the Jews' inability to correctly interpret, understand and predict what was happening.

Another common element is the fact that Jewish life during the Holocaust was lived in the midst of chaos, in the shadow of death. How were people able to carry on in such circumstances? How did they react? What kept them alive?

The contradictory aims of the German leadership represent another facet common and present throughout the Holocaust: though the army was fighting a world war, the SS was dead set on fighting a war for the extermination of the Jews. There was constant tension between these two goals, though the conflict between them was resolved in different ways in different places and at different times. Mr. Basch's reflections present the backbone of the movie as this conflict was resolved in Hungary: the race of the Germans to annihilate the last great concentration of Jews left in Europe in 1944 before they lost World War II.

As such, the movie can be used as a teaching tool to bring these more general themes to the fore, while examining the specific situation of the tragedy of Hungarian Jewry during the Holocaust. It can also be used to teach a number of subsidiary subjects: the story of Raul Wallenberg, Righteous Among the Nations; the steps in the extermination process, including the deportation of the Jews to camps and their journeys across Europe in sealed cattle cars; and the horrors of Auschwitz, the extermination and labor camp that has most come to symbolize the Holocaust.

The movie's approach to the testimonies of the five survivors is novel: their reflections on given subjects are spliced together in such a way that they practically finish each others' sentences. This creates a very dynamic, yet cohesive, account that neither gets bogged down nor becomes monotonous. Captions that are added to the testimonies serve to provide historical facts.

In line with Yad Vashem's pedagogical philosophy, the movie does not start with the Holocaust, but introduces us to the five survivors whose stories are featured in the film during their childhoods and prewar lives. Each of Irene Zisblatt, Alice Lok Cahana, Bill Basch, Renee Firestone and Tom Lantos describe their lives in five different places in Hungary on the eve of the war, and as we go back to these places with them, we get a glimpse of prewar life in the small towns and big cities of Hungary. What seems to be a common thread running through the prewar lives of each of these survivors is that they and their families were a part of the fabric of Hungarian life; they felt Hungarian. Renee Firestone relates that she had non-Jewish friends, and dated non-Jewish boys. Tom Lantos (the only Holocaust survivor to have become a member of the U.S. Congress) says of his hometown of Budapest, that the bulk of the Jews there were utterly assimilated and deeply patriotic, but at the same time were enormously proud of their Jewish cultural heritage. As Alice Lok Cahana says, "Judaism was our religion, but we were Hungarian." It was possible to be both Hungarian and Jewish – in the days before the war they were not mutually exclusive.

Once the war began, however, each of our survivors began to hear stories of what was happening to the Jews in other places in Europe. Irene remembers that there were refugees who came to Hungary after running away from Poland. On Friday nights, her father and the other Jewish men in her tiny town of Polena would go to synagogue and would bring these refugees home with them for dinner. She remembers hearing stories of atrocities; of babies being literally torn apart limb from limb. Alice has similar memories. But, as Alice and Irene concur, no one could believe these stories. Renee articulates how most of the Hungarian Jews felt: Hitler was in Germany – it was very far away, it didn't have any bearing on Hungary. And as Tom states, there was a naïve, patriotic feeling that the Hungarians don’t do the type of things about which they were hearing.

In time, however, the Jews began to realize that their situation was dangerous. Renee cites the turning point as the passing of the restriction that forced Jews to wear the Yellow Star. As she says, the Hungarians became worried because they knew the Jews in Poland had had to wear the star. And Tom reflects that the dark side of the Hungarian national character became more and more obvious. Jews lost their jobs and their businesses. There was a Hungarian Nazi movement, the Arrow Cross, and this became the most hated and feared group. Irene remembers that when she and her Jewish neighbors and family were actually deported, Hungarians whom she had thought were their friends turned against them: their friends and neighbors stood watching the deportation from both sides of the road yelling, "It's about time!" It was traumatic: these were the people she had gone to school with, her neighbors, their children. She asks a question specific to the Jews of Hungary and yet not specific at all in the history of the Holocaust throughout Europe – why did they hate us all of a sudden?

The film then traces the route taken by each of the survivors once the Nazis began their vastly accelerated campaign to do away with Hungarian Jewry, despite the fact that they were losing World War II. As Dr. Randolph Braham, a Holocaust historian and a survivor himself, puts it, there were two wars: a military war and the war of the SS directed against the Jews. It is clear from the testimony what the priorities of the SS were.

There are many poignant and telling moments in the film. Irene betrays the utter naiveté of the Hungarian Jews as she discusses the deportations from the makeshift ghettos where thousands of people were packed together, patrolled by Germans with dogs. "One day," she remembers, "they announced that everyone who wanted to go to work…to the vineyards to make wine should come out. Everyone voluntarily, gladly came out and went on the train because this was hell and to go to work in a vineyard to make wine was heaven." The viewer is appalled by this – can it be that in the spring of 1944 the Hungarian Jews were still so ignorant of the fate of the Jews elsewhere in Europe? Ignorant of the cattle cars, ignorant of the camps? Yet as discussed above, the self-defense mechanism and the instinct for self-preservation – the need for hope – kicked in. When he saw the cattle cars, Irene's father had a natural and logical explanation: it was wartime – the Germans had clearly run out of passenger trains so they had to use whatever was on hand. Irene accepted his explanation. However, she began to suspect that the cattle cars were far from normal when she heard the metal-on-metal of the bolts closing and locking them in. During the awful journey in the crowded cattle car, her father found a crack between the wooden slats. He looked out and was finally forced to confront reality. He said, "I don't think we're going to a vineyard. We just crossed a border and we're going towards Poland." And Irene remembers that as soon as he said "Poland," she was reminded of the story about babies being torn apart and thrown into the Dniester River. She held onto her little brother, who was 2 1/2 years old, even more tightly and swore, "They'll never take him from me."

Of course, we will find out later that Irene's brother and sister were indeed taken from her, together with her mother, on the ramp at Auschwitz.

All three of the survivors who reached Auschwitz have recollections about the journey in the cattle car, the arrival on the ramp, and the selection process in which they lost their families. Adding another level and more intensity to the movie, the testimony of Dr. Hans Münch, a former Nazi doctor at Auschwitz, is included as well. Münch confirms that what the survivors are speaking about was "a very simple process", and a "very primitive" one. He describes the way selections were performed at Auschwitz, the long lines, the finger of the German pointing to the right or to the left, condemning some to death and others to life as slaves.

Another of the more poignant stories is told by Renee Firestone. She remembers a bathing suit that her father had brought her when he was away on one of his routine business trips before the war. Worried and depressed, she had put it on under her clothing when she heard the boots of Nazi soldiers on the stairs of her house in Uzhorod, because it reminded her of happier times. When she arrived at Auschwitz and was forced to shed the bathing suit while being processed as a prisoner, she remembers that she had a premonition: if she left the bathing suit behind, everything that meant anything in life to her would be left behind as well. One day, in a group of twenty men that was passing, she suddenly recognized her father. Her first thought was to hide. As Renee remembers, her father was the kindest human being and always used to help everyone. "It was terribly painful seeing him with his shaved head and his uniform like a prisoner." She wondered how he would feel if he saw her, with her shaved head, dressed in rags. She wanted to hide so he wouldn't be able to see her, but at that moment their eyes locked, and she saw the tears rolling down her father's cheek. That was the last time she saw him.

Alice, who was 15 when she arrived at Auschwitz, also reminisces about her father. She remembers that there were 1,000 people in every barrack in Birkenau. The bunks were so crowded that if one person turned, everyone had to turn. With one blanket for every ten women, she was always cold at night. During the time she was at the camp she had a recurring dream: her blanket had slipped off her while she slept, and her father had come to put the blanket back over her. Then she would wake up and it was dark and cold. As she says, the camp was "a madman's hell."

There are many other touching moments in the movie, and a number of very memorable stories. Bill Basch and Tom Lantos discuss Raoul Wallenberg. As Tom remembers, "You were a hunted animal 24 hours every day. Had it not been for Wallenberg, neither I nor the other tens of thousands of others would have survived."

Irene discusses medical experiments that were performed on her, and Dr. Münch states, "For all those who wanted to conduct experiments on human beings, [Auschwitz] was a thankful workplace."

There is a discussion of the Nazi frenzy to kill the Hungarian Jews, a frenzy that cannot be explained logically. The Nazis were in a race against time; they diverted manpower and precious means of transportation that could have been used to fight the war they knew was lost, in order to deport almost 440,000 Jews of Hungary to Auschwitz in 56 short days and murder most of them. During this period, the gas chambers and crematoria could not cope: the Nazis had to use special pits to burn the bodies outside. Here, again, Dr. Münch confirms that there were mass graves that were about 8X10 or 10X10 meters wide. Wood was piled on the bottom and set on fire, and then the bodies were thrown over it. It is particularly chilling to hear this testimony from the mouth of a German doctor: if the fat burned, then the grave was working. More and more bodies were thrown into it. Münch says, "[It was] that simple."

Alice Lok Cahane, confronted with the enormity of the camp and the atrocity of the murder process, reflects, "Somebody had to plan this. Somebody had to put it on a map." And there is additional testimony by Dario Gabbai, a Greek Jew who worked as a member of the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz – one of only four alive when the movie was made – who describes the actual murder process.

What kept our survivors alive? For Alice, it was her relationship with her sister Edith. For Irene, it was a realization: "They didn't even let us die when we wanted. So I thought of something: 'They took away my parents, they took away my identity, they took away my siblings, they took away my possessions. There is something that they want from me.' And then I thought of my soul. And I said, 'They're not going to take my soul.' And I decided right then and there: 'I'm going to get up from this mud and I'm going to fight, because I'm not going to become ashes.'"

The movie continues to follow the five survivors through the trauma of liberation. At this point, the testimonies of three U.S. army veterans who liberated the concentration camps are included. Each of these veterans, Warren Dunn, Dr. Paul Parks, and Katsugo Miho, tells of the horror they witnessed with their own eyes.

The survivors fought to put their lives back together. All agree that it was very difficult. As Alice, who symbolically buries her beloved sister Edith in the movie, states, "For us, liberation wasn't the last day." There is a particularly poignant scene when Renee returns to her childhood home, to a house that she remembers as manicured and well-taken care of, to find it neglected and overgrown with weeds. Trying to enter, she finds the gate locked. Choked with sobs, she can only repeat over and over, "It doesn't open, it doesn't open," as if she were talking about her family and her past that is locked and gone forever, instead of just the gate.

The importance of The Last Days is that it opens this gate for us into the world of Hungarian Jewry before the war, and into five individual stories of what became of Hungarian Jewry during and after the war. Yet, the movie also contains an overarching theme presented throughout that transcends the story of Hungarian Jewry: that the Holocaust must be taught as a chapter in the long history of man's inhumanity to man. It is perhaps the culmination of the kind of horror that can occur when man loses his integrity, his belief in the sanctity of human life. As Steven Spielberg says in the prologue to the film, "We have to recognize that people are not born with hatred; they acquire it. We have the responsibility to listen to the voices of history so that future generations never forget what so few lived to tell."

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue