Since the beginning of the twentieth century, film has evolved into the primary medium through which we learn about the world and through which we form our perceptions about personalities, places and events. The motion picture is a special and invaluable resource that conveys the impression of immediacy and authenticity for us. It takes the viewer inside a certain topic and creates the illusion of truth more than any other medium. It contains within it many other art forms. It carries over the image from photography, painting and other visual arts; it carries over the melody and harmony from music; it carries over words and metaphors from literature and poetry; it carries over performance from the stage and drama. Therefore, film creates an art form of high verisimilitude – it seems to create something close to life itself on the screen.

Films are thus an invaluable resource that give the audience a different sort of understanding of past events as well as a deeper insight into them.

Yet, precisely for this reason, films are also dangerous:

“Of all art forms, film is the one that gives the greatest illusion of authenticity, of truth. A motion picture takes a viewer inside, where real people are supposedly doing real things. We assume that there is a certain verisimilitude, a certain authenticity, but there is always some degree of manipulation; some degree of distortion.”1

The certain authenticity and illusion of truth has its advantages of bringing the memories of the Holocaust into viewers’ daily lives, making them witnesses and helping them to understand the complex past events and their various outcomes. On the other hand, film has the power to manipulate and to distort these memories and to use them for narrow individual interests. The filmmaker confronting the Holocaust has unique power to create a sensory experience for the viewer. She or he stands before the difficult task of finding an appropriate language and a representative image for that, which is mute or defies visualization.

The complex and sometimes contradictory ways in which the filmmakers deal with these aspects of the Holocaust shape our feelings towards the historical events, which may vary from compassion to indifference and ignorance, from the desire to forget to the need to understand.

On the other hand, it is impossible to portray the Holocaust in film. As Stephen Spielberg has said, “[t]he Holocaust is perhaps the most difficult story to put on film, and I think the reason Hollywood hasn’t made many Holocaust pictures is because it’s an ineffable experience only understood by those who survived the camps.”2

Regarding the use of visual material in films, it is evident that an iconography of certain pictures has developed. Many movies and documentaries use the same expressive pictures and images, like the pictures of the liberated camps for example. These pictures have turned into visual icons. They are used in documentaries and movies to gain the impression of authenticity. But not only are these icons of the Holocaust part of movies that depict the persecution and extermination of Jews like in Schindler’s List or The Pianist. They are also beginning to be part of films that have a different perspective on the Holocaust or sometimes do not actually refer to the Holocaust at all. These films use the icons to compare certain events to the Holocaust.

There is a chance that the Holocaust can be trivialized and even exploited by those who simply have access to the media and claim to present the “truth” of World War II. Nevertheless, it is primarily through motion pictures that the mass audience acquires knowledge and understanding about the Nazi era and its victims. Therefore, it is important to take a closer look not only at the content of the film but also at the filmmaker and his or her intentions, and to analyze the perspective as well as the audience’s reactions.

As for the authenticity, it is important to emphasize that any film – be it fiction, documentary, or even a survivor’s account based on his or her experience – can provide only a part of the “truth.” Each individual story is a vital piece of the puzzle – the reality of the Holocaust.

As long as there are Holocaust deniers who proclaim that the Holocaust did not happen, there must be active resistance by those who know that it did. The luxury of forgetting is not possible. Film is therefore an immensely powerful and important tool in determining contemporary awareness of the Holocaust, commemorating the dead, informing and teaching, and helping us to understand and to remember.

As the theme of this newsletter is Defiance and Rebellion during the Holocaust – Marking 70 Years since the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, this article will present two films that revolve around the topic of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising that left their mark on the way we remember and understand the Holocaust and Jewish resistance. These films can be used in classrooms as a means of teaching about Jewish uprisings and different forms of Jewish resistance.

The Pianist (2002) - Movie Poster

"The Pianist"

Roman Polanski

France-Poland-Germany-UK, 2002/ English, German and Russian/ 150 minutes

The Pianist, directed by Roman Polanski is the dramatized story of Holocaust survivor Wladyslaw Szpilman. It is also a story of war, despair, ghettoization and deportation, and ultimately, of survival. The Pianist tells the story of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a celebrated Polish-Jewish concert pianist (played by Adrien Brody) living with his family during the Nazi invasion in Warsaw, with everything that this entailed for the Jews. Thanks to an extraordinary combination of faith, courage, luck, the will to live, and the help of some non-Jewish friends, Szpilman manages to remain in Warsaw where he survives the German occupation by hiding in abandoned apartments and in the city ruins. From his hiding places, he witnesses the Jewish Warsaw Ghetto Uprising of 1943, and the Warsaw Polish Uprising of 1944.

In the beginning, Szpilman finds himself participating quite by chance in the preparations for the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. However, shortly before the uprising starts, he manages to escape from the ghetto and to find an apartment on the Polish side of Warsaw with the assistance of Polish helpers. He helplessly watches the uprising and its suppression from the window of his apartment.

Szpilman's struggle to stay alive against all odds and his rescue by a German soldier in the last part of the movie provides a dramatic climax for a film filled with drama. Szpilman's rescuer, Wilhelm Hosenfeld, was captured by the Soviets and eventually died in a prisoner-of-war camp. In 2008 he was awarded the title “Righteous Among the Nations.”

Unlike other movies about the Holocaust, The Pianist maintains its protagonist's point of view, allowing Polanski to create an intimate production of epic wartime dimension, drawing a direct parallel between Szpilman's determined, and often extremely precarious, existence, and the almost total destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto. Even the perspective of the heroic uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto is one of a passive eyewitness, which creates a visual distance to the events for the viewer.

The film can be used for educational purposes in order to enrich the students’ knowledge about the Holocaust and the historical circumstances surrounding Szpilman’s story.

Educators can discuss the Jewish fighters who struck back at the Nazis and fought against impossible odds. These fighters who were barely armed knew they could not win against an overwhelming German army. But they decided to fight against all odds for their honor. Students should recognize that these heroes served as inspiration for others and proved that the spirit of resistance could not be destroyed.

At the same time, students can discuss Szpilman’s decision to leave the ghetto as yet another form of resistance. Heroism can be found in the non-violent responses to the persecution and in the preservation of one’s own humanity in the midst of an inhuman situation. Szpilman decides to defy the Nazis by escaping them and by trying to survive at all costs without giving up against all odds, which makes him likewise an inspiration to others.

Educators can address the different types of resistance by adding more examples. In one scene, Szpilman’s siblings reject a Nazi offer to remain in the ghetto and instead join their parents and siblings at the “Umschlagplatz” from which they will be deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. The siblings choose against the separation, in favor of sharing their family’s fate, whatever it might be. This is also a form of resistance. The Nazis intended to destroy human values. The ghetto conditions of starvation, diseases, lack of medication, overcrowding, forced labor, abuse, humiliation, and death forced people to wage a day-to-day struggle to survive and eroded the stability of the family unit. The siblings resist the Nazi pressure to put self-preservation above everything, by choosing human values of family life.

Additionally, the film can serve to arouse discussion concerning several dilemmas Jews had to face in the Warsaw Ghetto. In one scene Szpilman and his brother Henryk are asked to join the Jewish police to help the German occupiers control the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto. They decide to reject the opportunity to create a better life for their family within the ghetto because they don’t want to help the Germans. Jews faced these or similar dilemmas every day and it is important to show students that the situation was one of “choiceless choices”.

The viewers have to keep in mind that the perpetrator pictures were taken with a specific intention. These photographs were taken to prove the suppression of the uprising as seen by the perpetrators. They bare the cynical title “Es gibt keinen jüdischen Wohnbezirk in Warschau mehr”. (There is no longer a Jewish quarter in Warsaw). Polanski reproduces the view of the perpetrators through Szpilman’s eyes. These filmic scenes can serve to take a closer look at icons of the Holocaust and can lead to a critical discussion about the power and disadvantages of images. They can also lead to research and a discussion of different images and the perspective and intentions of the specific photographers.

Regarding the director and the images chosen for the film, it is important to point out that Roman Polanski decided against using any archival footage taken by the German occupiers of the Warsaw Ghetto. However, he bases his filmic pictures of the ghetto on the German footage. Regarding the last days of the Jewish uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto, Polanski’s images of the suppression recall the icons from the German Stroop report (named after the SS commander Jürgen Stroop). The original photographs of the Stroop report >>>

Uprising (2001) - Movie Poster

"Uprising"

Jon Avnet

USA, 2001/ English/ 153 minutes

Another movie which dramatizes the story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising is the movie Uprising from 2001 which was directed by Jon Avnet.

As opposed to The Pianist, this film tells the story of the uprising from the point of view of a small group of courageous Jewish residents of in the Warsaw Ghetto who create the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB) in order to fight for human dignity against their German oppressors. It shows the preparations for the armed resistance until the destruction of the ghetto, and helps to dispel the myth of Jewish passivity.

Uprising is very accurate in delivering historical background and recreates the armed struggle by adding the detailed events of smuggling operations, building bunkers, arming the residents and the actual fighting. It brings the events to life by giving human faces to those who fought, as well as those who died in battle.

Among these are the resistance leader Mordecai Anielewicz (Hank Azaria), Marek Edelman (John Ales), Yitzhak "Antek" Zuckerman (David Schwimmer), Zivia Lubetkin (Sadie Frost), Tosia Altman (Leelee Sobieski) and Simcha "Kazik" Rotem (Stephen Moyer).

The events are screened in such a detailed fashion, including real events, names, and documents, that the viewers get the impression they are witnessing the actual events or watching a documentary.

The film additionally deals with the personal dramas and different moral dilemmas faced by the Judenrat (Jewish council), groups and individuals. The film further raises difficult questions about human behavior concerning actions of individuals, groups, nations and their decisions. By focusing on these decisions, students can gain insight into history and human nature.

One of the most tragic examples of the moral dilemmas that confronted the Jews is that of the Jewish policeman Kalel Wasser, who is considered a traitor among his people for serving in the Jewish ghetto police. He seems to have no mercy in carrying out German orders against Jews. He justifies his actions in terms of his desire to protect his own family, as the Jews who joined the ghetto police were promised legal immunity for themselves and for their relatives. However, in the end he rebels against his superiors, joins the underground, and proves to be as courageous as his comrades. His situation reflects similar stories of hundreds of Jews who needed to make a "choiceless choice" between being loyal to their families and being loyal to their people.

The film provides a context within which students can discuss the use and abuse of power, individual choices, roles and responsibilities of individuals, groups, organizations, and nations during the Holocaust (collaborators, perpetrators, bystanders, resisters).

The film also gives the viewers a detailed account of the complicated nature of resistance during the Holocaust. It provides an insight into different ways of resisting the Germans and dealing with the unbearable conditions that the Germans forced upon the Jews such as starvation, disease, lack of medication, overcrowding, forced labor, abuse, humiliation, and death. The non-violent Jewish resistance consisted of building underground soup kitchens, schools, hospitals, and even maintaining a community life to try to help the residents survive the harsh conditions. Another type of spiritual resistance the film mentions is the creation of the famous Ringelblum archives Oneg Shabbat to document daily life in the ghetto under German oppression. Students can research these different types of defiance.

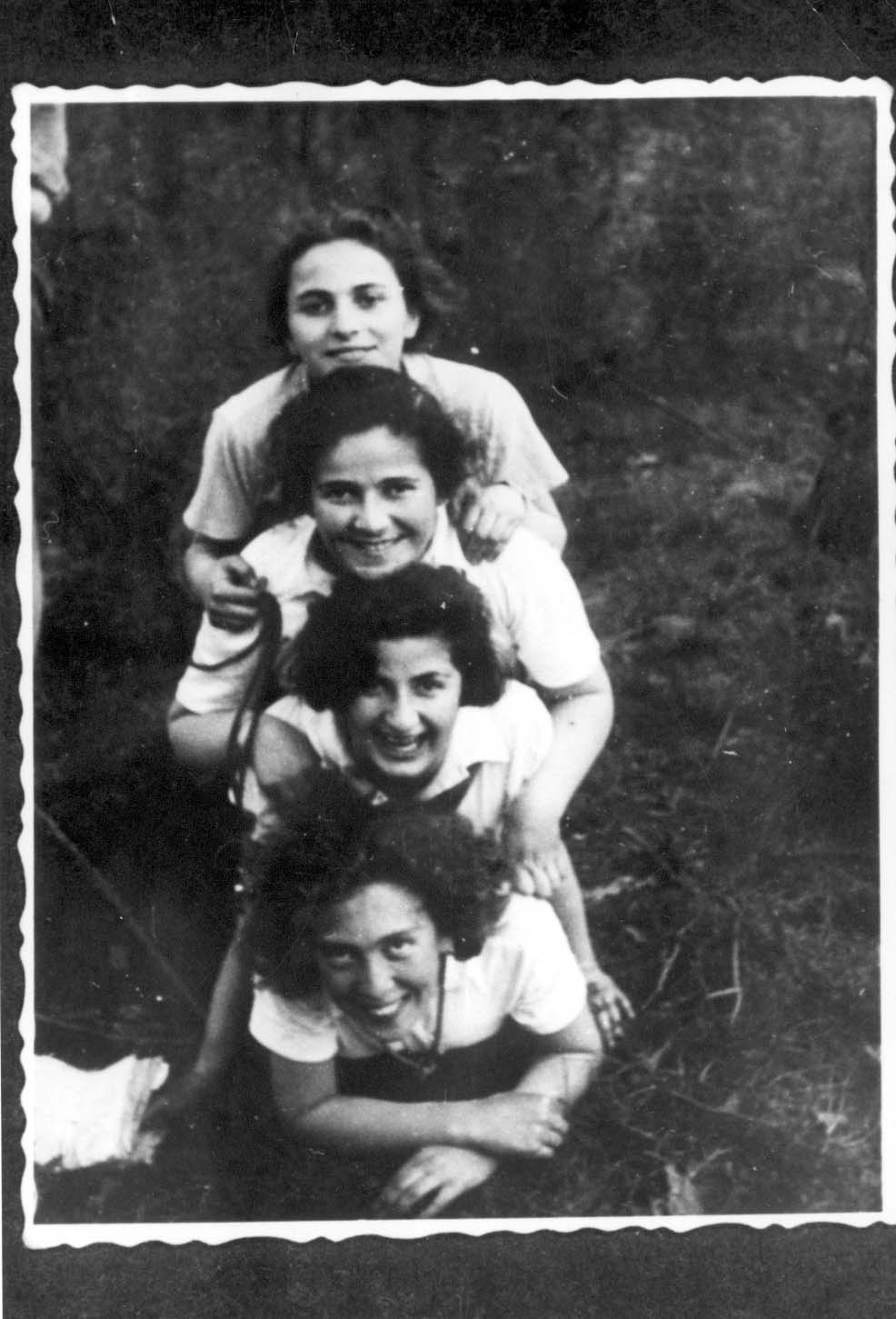

The film deals with the relatively unknown story of female couriers who traveled through Nazi-occupied Europe. These couriers were young and brave girls who risked their lives in order to serve as the lifeline between isolated Jewish communities. Disguised as non-Jews, they transported documents, papers, money and ultimately also ammunition and weapons across borders and into ghettos. They passed on messages between friends, family members and communities and later on warned Jews of the approaching danger. It was easier to rely on Jewish women for this difficult and dangerous task as Jewish men could be easily identified as Jewish (due to their circumcision) and as all men in occupied Europe were subject to forced labor for the German war economy.

In the film Tosia Altman agrees to become a courier and to smuggle weapons into the ghetto. In one scene she is given the assignment of smuggling a map of Treblinka to England. On her mission she is suddenly stopped by a German soldier and told to go into a shack where she is told to strip naked. Before she has to take of her shoes in which the map is hidden, the Jewish policeman Kalel comes to assist her and to get Tosia's interrogator out of the shack. This leaves her enough time to get dressed and escape.

The scene clarifies the difficulties connected with resistance activities such as smuggling documents or simply leaving the ghetto. These brave women became an inspiration and a spark of hope to the Jews and they prove that Jewish women were as involved in the resistance as Jewish men were.3

The film focuses especially on moral questions, human dignity, and the change of moral codes as the conditions in the ghetto worsen. Thus, asks Mordecai Anielewicz in the film, more than once: “Can a moral man maintain his moral code in an immoral world?”

The discussion questions and classroom activities can focus on moral choices under the horrific conditions in the ghetto. One such example is that of Dr. Janusz Korczak, the director of the orphanage in the Warsaw Ghetto, who shows dignity and keeps his moral codes until the very end. Even though he is able to leave the ghetto and save his life, he refuses to abandon the children. One of the most powerful scenes in the film is the procession of Korczak and the children from the orphanage to the train, which will deport them to their inevitable death in the Treblinka extermination camp.

The film also highlights Jewish honor and Jewish responsibility. During a meeting between the head of the Jewish council Adam Czerniakow, and the resistance fighters Mordecai Anielewicz and Yitzhak Zuckerman in which the two try to persuade him to support the armed resistance, Czerniakow says: “Jewish honor! A father who is hiding his son is not honorable? A rabbi who is teaching a child his lesson is not honorable? A mother who is taking care of her children and many more – she is not honorable, either. No! For you, honor – honor can only come out of the barrel of a gun. You talk about honor. I talk about Jewish responsibility.”

He criticizes their narrow view of honor and adds yet another perspective – of all of those who simply don’t have the strength or are unable to fight an armed struggle such as old people and children or who don’t believe in violence. He works with the Germans to try to minimize harm. In his opinion, any kind of armed resistance will be answered by severe retaliation by the Germans against innocent Jews. Thus, it is his responsibility to protect innocent Jews.

Czerniakow’s perspective stands in contrast to the view of the armed resisters, whose view is clearly emphasized in Mordecai Anielewicz’s last letter from his bunker in the ghetto to Yitzhak Zuckerman:

“April 23, 1943

It is impossible to put into words what we have been through. One thing is clear, what happened exceeded our boldest dreams. The Germans ran twice from the ghetto.

[…]

It is impossible to describe the conditions under which the Jews of the ghetto are now living. Only a few will be able to hold out. The remainder will die sooner or later. Their fate is decided. In almost all the hiding places in which thousands are concealing themselves it is not possible to light a candle for lack of air.

With the aid of our transmitter we heard the marvelous report on our fighting by the "Shavit" radio station. The fact that we are remembered beyond the ghetto walls encourages us in our struggle.

Peace go with you, my friend!

Perhaps we may still meet again! The dream of my life has risen to become fact. Self-defense in the ghetto will have been a reality. Jewish armed resistance and revenge are facts. I have been a witness to the magnificent, heroic fighting of Jewish men in battle.

M. Anielewicz”4

Uprising provides further insight into the twisted and sadistic instruments of the German Army and the Nazi propaganda machine. Uprising, as opposed to The Pianist, makes the German propaganda machinery itself a subject of discussion. The film enables the viewers to reflect about the nature and the construction of historical images. The preparations and the implementation of the uprising are consequently portrayed through the eyes of the Jewish fighters.

Another plot addresses the relationship between SS-man Stroop and the National Socialist film director Fritz Hippler. The scenes show the importance of propaganda for Nazi Germany and the origin and simulation of certain pictures. Uprising also uses pictures from the “Stroop album” but in comparison to The Pianist, all these pictures are clearly identified as products of Nazi propaganda by focusing on Hippler’s camera. This way, the historical origin is being disclosed.

Conclusion

Each time a filmmaker decides to recreate life during the Holocaust she or he will have to ask the question of how to portray it, how to avoid exploitation and whether there are events that should not be pictured, imagined and fictionalized. The films will always be reduced to his or her own knowledge.

That brings us back to the initial question of which story should be told, for which reasons, and how it should be told.

The use of film in the classroom is excellent as a teaching methodology, and using historical films in addition to studio-produced movies provides students with a different understanding of an historical time period. If teaching the Holocaust through films, the educator should consider what is age-appropriate, the nature of students’ preconceptions, biases, and emotional state of mind based upon cultural and national backgrounds. This requires appropriate student preparation in each situation.

The films depicted above are important ones because they can help overturn popular misconceptions about Jewish victimization and passivity during the Holocaust and serve as a source material for discussions about the difficulties of resistance, uprisings and ethics in inhuman times.

- 1.Annette Insdorf, professor of film studies, in an interview screened in the documentary: Imaginary Witness: Hollywood and the Holocaust, by Daniel Anker, 2004.

- 2.Steven Spielberg, producer and director, in an interview screened in the documentary: Imaginary Witness: Hollywood and the Holocaust, by Daniel Anker, 2004.

- 3.https://www.yadvashem.org/articles/general/couriers.html

- 4.[M. Kann], Na oczach swiata ("In the Eyes of the World"), Zamosc, 1932 [i.e., Warsaw, 1943], pp. 33-34. Written to Yitzhak Zuckerman. Source: Documents on the Holocaust, Selected Sources on the Destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland and the Soviet Union, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1981, Document no. 145.

.jpg)