- The “Bericha” was made up of veterans of the Palestine Brigade, a fighting unit consisting of Palestinian Jews, which Great Britain created to help it fight in its war effort.

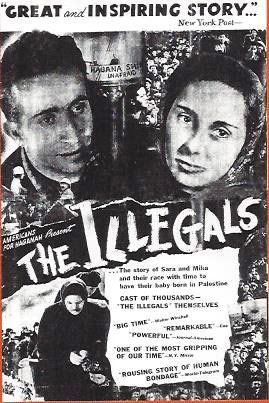

"The Illegals"

"The Illegals" (Hebrew: Lo Tafhidenu)

Director: Meyer Levin

Eretz Israel (British Mandatory Palestine), 1947

English, Hebrew, Yiddish / 72 minutes (B&W)

This 1947 film addresses illegal immigration into Palestine after the Holocaust when survivors tried to reach a new home. This review examines the film and its importance in using it in the classroom.

Introduction

Holocaust survivors’ testimony is an invaluable resource that not only gives the audience a degree of understanding as to the events the survivor endured many years before, but also puts a face to those experiences. It is difficult, however, for those who hear survivors recount their personal stories, to equate the elderly person they see before them with the younger person he or she was then. By using supplemental visual materials such as photographs, documents, and film, listeners can better comprehend the situations the survivor relates to them, and thus gain a deeper insight to their stories.

One such film is Meyer Levin's “The Illegals.” Filmed in 1947, this docudrama allows the viewer to see survivors in the actual historical context of their post-Holocaust lives and struggles.

Reeling from the enormous personal and collective losses they suffered during the holocaust , many of these young survivors wandered aimlessly across Europe, homeless and stateless, on a continent that in many places remained rampantly antisemitic. Europe , for them, had been transformed into an enormous cemetery haunted by traumatic memories of the loved ones they had lost. They yearned to rebuild their shattered lives in the Jewish national home, with a name familiar to every Jew, both religious and secular: Eretz Israel (pre-state Israel).

This was to be no easy undertaking. The biblical Eretz Israel was, in post-war actuality, controlled by the British Mandate, which curtailed Jewish immigration. For stateless Jews with no papers, Palestine would be an elusive goal at best.

However, before these Jewish Holocaust survivors could even attempt to enter Palestine, they had to first be in a geographic position to travel there. Guiding this she’erit hapleita (surviving remnant) of homeless Jews across hostile borders to safe gathering points in western Europe, and from there to Palestine, was a clandestine group of Palestinian Jews that called itself the “Bericha.”1 Upon reaching the relative safety of collection points in western Europe, these survivors were to be secretly helped by members of Aliyah Bet (the illegal immigration program) to continue their trek onwards to Palestine. The story of how this was accomplished - the mass exodus of 300,000 homeless people, first fleeing over land from eastern to western Europe, and then over the sea to attempt to run the British blockades into Palestine - is an amazing one, a story of great hardship and perseverance.

Film: The Illegals

In 1947, an intrepid American filmmaker named Meyer Levin captured this story in his film “The Illegals.” In Levin’s docudrama, the viewer is offered a fascinating window into the lives of the young men and women who partook in the illegal immigration into Palestine. It is not a series of interviews, but rather allows the viewer to bear witness to real events as they unfold, and is confronted by the unshakable drive and fortitude of these survivors as they make their resolute journey to Eretz Israel.

An American Jewish filmmaker, Meyer Levin was born in Chicago in 1905. In 1943, he worked with the American army in Europe as a war reporter. In April 1945, he and French photographer Eric Schwab were the first ones among the American liberating forces to enter the horrific concentration camp of Ohrdruf, a sub camp of Buchanwald.

Having seen first hand the catastrophic fate that had befallen the Jewish people during the Holocaust, the focus of Levin’s work and energy became their struggle to create new lives in Palestine.

To this end he filmed the docudrama “The Illegals” while accompanying groups of Jewish refugees as they made the difficult and perilous journey to Palestine. To contextualize the events he was filming Levin weaves into the story the subplot of a fictional young married couple, Sara and Mika Wilner, (played by the amateur actors Tereska Torres (Mrs. Levin) and Yankel Mikalwich,) two characters who serve to personify the unnamed thousands undertaking this mass exodus. At certain points in the film, Levin places these actors within the footage, and melds their story with the historical story that he is telling.

- 1. 1

The film, released in 1948 on behalf of “Americans for Hagganah,” is in Yiddish, with Levin himself providing the film’s terse narration. As the film opens, we are introduced to Mika and Sara, and are told nothing more about them than that they each survived unspecified concentration camps, met each other, and married. Against the background of the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, still existing relatively untouched in 1947, these two scramble, camera in hand, over towering mounds of debris to pose for pictures. The narrator tells us that Sara and Mika “loved to photograph each other, perhaps to make sure that that they really existed.” Levin’s use of symbolism here is powerful: these two lone survivors stand phoenix-like upon the ruins of their destroyed people, reconfirming their shaky triumph of life over death.

But this life cannot continue in Poland.

The pregnant Sara tells Mika that she cannot bear the thought of giving birth in Poland. “This is no place for a Jewish child to live,” she tells Mika. We must find a way to go to our own home.”

The couple agreed to find a way to leave the ruins of their former life behind in favor of a new life in Eretz Israel. Without proper papers, however, they will need to go by way of an underground railway, run by the “Bericha” organization. On the first leg of this journey, they join a group of actual refugees in Czechoslovakia and led by “Bericha” guides, make an attempt to cross the Polish border at night. Mika, along with one of the guides, is caught and put in a Polish prison, but since Sara does not know of his whereabouts, continues on to Vienna to the refugee gathering point of the Jewish Rothschild hospital. While groups begin the next part of the trip, Sara remains behind, hoping that Mika will soon join her. She finally realizes, however, that if she stays any longer “her baby will be born on a common bed of displaced persons in their enemy land” and is advised by the “Bericha” headquarters to continue. Mika will follow when he eventually gets released from prison. Levin accompanies Sara’s group with his camera, and some of the images we see of this scene are the weary people, lugging small suitcases, holding babies and toddlers, who cross forests by foot and travel at night in crowded trucks. They rest in tight quarters fully clothed and ready to start again in an instant. Levin focuses on them relishing bowls of simple soup and bread, eating with a hushed, intense urgency, and steadily spooning food into the mouths of their young children. He uses this image of eating again and again in the film, reminding the viewer of the unspoken deprivation and starvation these people suffered only recently.

Embarking on the next leg of their journey, now to France, the camera records the survivors climbing into the freight cars that will carry them there. This jolting image is painfully reminiscent of the Nazi footage taken a few years prior on the ramp at Westerbork, Holland, where Dutch Jews boarded the death trains to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The irony of this juxtaposition is not lost on Meyer Levin. In one of the most understated yet powerful parts of the film when we see the weary passengers huddled on the floor of the car, some of them eating, some engaged in quiet conversation, many lost in thought while confronting their own personal demons. One man searches the walls of the car with a flashlight.

“What are you looking for?” the woman next to him asks.

“My name. I wrote it on the walls on my way to Auschwitz.” He says.

“They must have cleaned them off, “ Sarah adds quietly.

“But this time, no one forced us to go,” the first woman tells them both.

Another woman bolts upright out of troubled sleep, and cries out, terrified “where is this train going?”

“To France, to France,” her husband murmurs soothingly, patting her arm.

These two exchanges are all the viewer is offered as to the terrible past endured by these survivors. Their brevity and simplicity typifies the way survivors relayed events in their early postwar testimony. Their experiences were still so raw, painful, and overwhelming, that going into painful details, might lead to the collapse of their tenuous coping mechanism. For many survivors, it would take years, even decades, until they could tell their stories and come to terms with their loss. On a cinematic note, Levin consciously uses symbolism here as we do not see the actual cattle car in which this man was transported a few years before. It is a relatively early use of this symbol of extermination.

As Sara’s group travels to Italy to meet up with the clandestine ship, which will attempt to carry them to Palestine, Mika is finally released from jail and sets off to try and find his wife. The actor accompanies the refugees on a harrowing trek though the Alps, and Levin captures the determination and an unwavering drive of this group to continue on their exodus out of Europe. Elderly people are pulled up steep inclines, the younger, sure-footed men holding the infants as all wade through thigh-high snow until finally arriving in Italy. Although they have come this far, the journey is far from over, as they now await a ship that will attempt to sneak past the vigilant British navy and into Palestine. Sometimes refugees waited weeks or months for these ships to become available. The British authorities, insistent that the Jewish immigration quotas be respected, blockade the territorial waters of Palestine, and send the hapless refugees they catch to internment camps. The lucky ones are interned in Palestine itself, and have the comfort of being on the soil of Eretz Israel, even if not free. Most of those caught, however, are sent to internment camps on Cyprus.

On the Aliyah Bet ship “The Unafraid,” the fictional Mika and Sarah are reunited. In actuality, Meyer Levin, his cameramen, and the actors, accompany 853 refugees, including 150 babies and toddlers on the small wooden freighter as she sets sail for Palestine on December 11, 1947.

The refugees endure extremely cramped, overcrowded, and stiflingly hot conditions. They are told that to prevent detection they must hide below deck until the ship reaches open seas, and only then will they be allowed up on deck to breathe the fresh sea air.

Levin again focus on the resilience of these survivors as they stoically endure seasickness and misery. The “Bericha” leader tells his gathered passengers “we would like to sail this ship straight into the harbor of Tel Aviv, with colors flying and bands playing ashore.”

The camera pans over the uplifted faces listening to these words.

“But,” the leader continues, “When we approach Palestine, you must hide during every alarm. It will be stifling below, but this must be done.”

On the 12th morning of the voyage, off of the coast of Egypt, an Egyptian plane spots the ship, as the passengers scramble to hide below deck and under tarpaulins. The captain raises a Turkish flag, hoping to be taken as a mere cargo ship, but a British warship soon stalks the “Unafraid.” Using loudspeakers, the British captain tells the refugee vessel, “I believe you are Jews. When you enter Palestine waters, I will use the overwhelming force of my powers to board you.” Realizing that masquerading as a cargo ship has failed, the “Bericha” commander tells everyone that they can now come up on deck. Meyer Levin captures the dismayed passengers as they climb out from the sweltering lower decks. They emerge dazed and apprehensive. A young woman, drenched in sweat, collapses into the arms of her young husband as others, splashing water on their faces, gaze with frustration at the British warship.

Not being able to physically resist the British because of the number of women and babies onboard, the passengers show their defiance by hoisting the Israeli flag, prepare a banner bearing the ship’s name and sing Hatikvah, which would become Israel’s national anthem.

To symbolize the imminent rebirth of all those aboard in their new land, Meyer Levin adds the cinematic touch of showing a baby being born at this moment below deck. The next morning, one of four British warships pulls up alongside the refugee vessel. In one of the most dramatic moments in the film, Levin captures the British soldiers leaping on to the decks of “The Unafraid,” almost onto the very feet of the silent, resentful passengers gathered on the decks to watch them. Their faces suffused with anger and disappointment, the Jews maintain their restraint, and do not lift a hand in resistance. From here, this group would be sent to detention camps in Cyprus.

“They see Haifa before them,” says the narrator, “when hostilities end, the Jews and British will become friend among the nations. But for now, this becomes the survivors’ glimpse of Eretz Israel.” Giving voice to the aspirations and hopes of all the actual passengers on board, Mika and Sara gaze with determination at Haifa, vowing to move there some day with their children. The film ends as Levin again pans the defiant and wistful faces of these refugees, couples, elderly, children, and breast-feeding babies looking shoreward.

Conclusion

After an in-depth exploration of Meyer Levin’s 1947 film “The Illegals,” which addresses the illegal immigration into Palestine after the Holocaust, it is clear that this aspect of post-Holocaust life is an important aspect when studying the period. In the classroom, the focus is usually on the Holocaust itself without much emphasis on the survivors’ “return to life” after the war. Showing this film in the classroom will bring this issue to the surface, and due to the visual element that film provides, will also allow students to view the period as it occurred and understand the benefits of historical film footage. The use of film in the classroom is excellent as a teaching mechanism, and using historical films in addition to studio produced movies gives students a different understanding of an historical time period.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Yehuda. Flight and Rescue. New York: Random House, 1970.

- Litvin, Martin. Audacious Pilgrim. The Story of Meyer Levin. Woodston: Western Books, 1999.

- Fritz Bauer Institute. Hanno Loewy, “Retracing a Journey through Europe”

- “Palyam and Aliya Bet”

- T.F.B. "How Displaced Jews Get to Palestine.” New York Times, July 15, 1948.