Educators often approach Holocaust study from a historical point of view, deepening their students’ knowledge and understanding through the use of survivor testimonies, classroom discussions, films, books, and other disciplines. However, teachers may find that the world of art offers their students another path to processing this difficult and complex subject matter.

This learning environment presents a way to use art from and about Auschwitz in teaching the subject to your students.

In order to use art as a tool to teach about Auschwitz, the teacher does not have to be an expert in the field. Exploring each painting, looking in detail at what's represented in it and appreciating its artistic elements, together with the study of the context in which it was created and the questions each artwork raises, deepen our understanding of the Holocaust in general, and enable us to view Auschwitz as the human experience that that it was.

Note to the teacher:

In preparation to using art as an educational tool in learning about Auschwitz, teachers and students should familiarize themselves with the subject of Auschwitz and Art in/from Auschwitz.

Some of the art from Auschwitz served another function after the war. It served as evidence that confirmed Nazi criminality during various trials. An example of this is Yehuda Bacon's work which was used together with his recollection of the gassings, beatings, selections and the Sonderkommando revolt as proof in both Eichmann's trial in Jerusalem in 1961 as in the Frankfurt Auschwitz trial that took place between December, 1963 and August, 1965.

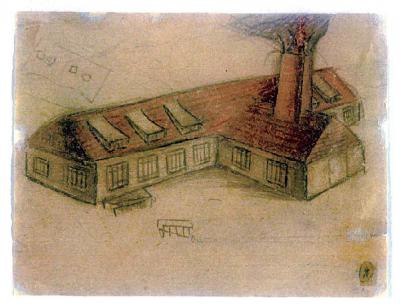

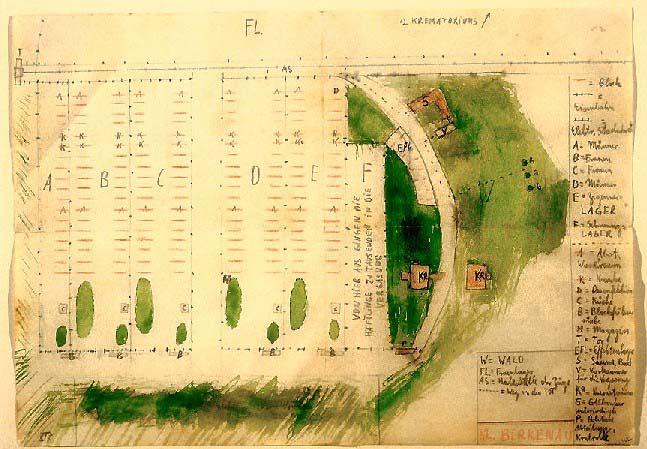

Yehuda Bacon had been transferred from Theresienstadt to Aushwitz-Birkenau with his family where upon arrival they were sent to the Theresienstadt Family Camp at Birkenau. Later on, after a Selektion performed by Josef Mengele, Bacon was sent to the men's camp. There, together with 20 other men, he had to carry wood and clothing from one side of the camp to another, including the crematoria. After liberation and after recovering from typhus, in June 1945 Yehuda Bacon made drawings from his memory of the gas chambers and crematoria in Birkenau.

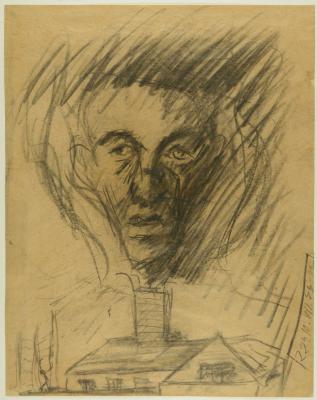

In the drawing In Memory of the Czech Transport to the Gas Chambers, we see the face of a man coming out of the crematoria, this man is his father. Bacon wrote the date of his death, in the gas chambers, in the lower part of his drawing as he knew exactly the date when his father, together with the thousands of Czechs who had arrived from Theresienstadt in December, 1943, had been killed in massive gassings that were carried out between July 10-12, 1943. Bacon portrayed him as coming out from the chimney of the crematoria, rendering testimony to the way in which he had died. Bacon painted it immediately after being liberated. He was afraid that if he didn't draw his father's face, he would soon forget it.

Yehuda Bacon's biography

Born in Moravská Ostrava in Czechoslovakia, in 1929. In 1942, he was deported with his family to Terezin, where he lived in the youth barracks and belonged to a group that produced the newspaper “Vedem” (We Are Leading). He studied with artists in the Ghetto. In 1943, Bacon and his family were deported to the “family camp” at Auschwitz. In 1944, he was transferred to the men’s camp and assigned to a labor group, which was assigned the task of gathering the murdered inmates’ belongings, and collecting the victims’ ashes for dispersal. The evacuation of Auschwitz being imminent, Bacon was sent on a death march to the Blechhammer camp, then by an arduous route to Mauthausen, and finally, to the Gunskirchen camp, where he was liberated.

Immediately following his release, he drew small sketches of the crematoria and gas chambers at Auschwitz, which would later serve as testimony in Eichmann’s trial. After immigrating to the Land of Israel, he studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art, where he eventually became a faculty member.

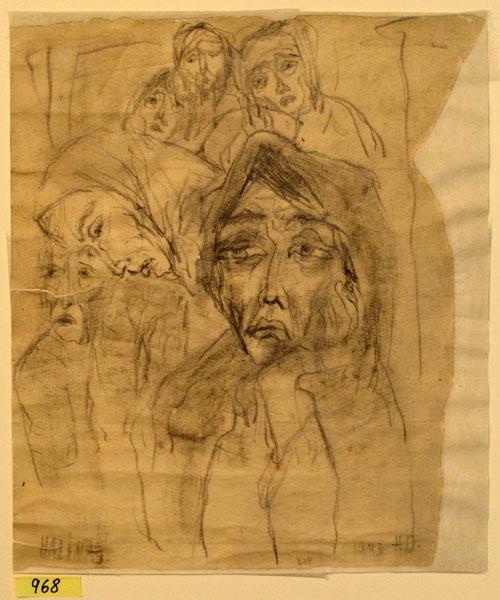

Although maybe most people wouldn't expect it, the most prominent form of art created during the Holocaust in Auschwitz and other camps and ghettos is portraiture. Portraits gave the subject a sense of permanence, it was a proof that they had been on this Earth and it gave them the hope that even if they wouldn't survive they would be remembered.

Halina Olomucki recalls that "While I was in Auschwitz-Birkenau someone told me, ‘if you live to leave this hell, make your drawings and tell the world about us. We want to remain among the living, at least on paper."

Their portrait also made them feel they were individual and unique human beings, in a place where all efforts were made to take their individuality and humanity away from them. Artists also made self-portraits claiming their own individuality.

Painting portraits was a means of psychological escape for some of the artists whilst painting them. Polish prisoner Franciszek Jazwiecki, who made around 114 portraits of fellow prisoners explained it further, "For a moment of happiness, or actually forgetting...I have been making pencil portraits in the camp. The portraits were made on the sly, in secret, and were a moment of forgetting for me. They took me to a different world, the world of art. I simply disregarded the fact that drawing was punished by death; I did that not because of courage. I just didn't pay any attention to the danger; it was so attractive to be and work in this world of mine..."

Halina Olomucki's biography

Born to the Olszewski family in Warsaw, Poland, in 1921. Died in Ashkelon, Israel, in 2007.

Olomucki's father died when she was a child. She grew up in Warsaw and received a Jewish, although not religious, education at a Yiddish-speaking school. With the German occupation in 1939, Olomucki and her family were deported to the Warsaw ghetto. She was conscripted to forced labor outside the ghetto walls. In May 1943, Olomucki and her mother Margarita were transported to Majdanek, where her mother was murdered. In May 1943, Olomucki was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. There, she was forced to work in the Union (Weichsel-Union-Metallwerke) ammunition factory. She was designated to paint signs for the barracks. With the approach of the Red Army in January 1945, she was evacuated on a death march to Ravensbrück, and from there to Neustadt-Glewe, where she was liberated on May 2, 1945. She returned to Warsaw in the hope of finding family members who survived, but to no avail. She moved to Łódź, where she married, and studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts until 1951. She was a student of the artist Władysław Strzemiński. In 1957, she moved to France and in 1972, immigrated to Israel, where she settled in Holon.

Olomucki portrayed daily life in the Warsaw Ghetto. After she was transported to the concentration camps, she continued to draw, using materials that she obtained through her assignments as a forced laborer. In Warsaw after the war, she found her drawings, which she had been able to smuggle out of the ghetto to a Polish friend, who had saved them. She also managed to find a few of the drawings she had hidden in Birkenau.

- Miriam Novitch, Lucy Dawidowicz andTom L. Freudenheim, Spiritual Resistance. Art from Concentration Camps, 1940-1945 (Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981), p. 17. As discussed in the online exhibition "The Last Portrait" http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/last_portrait/index.asp, accessed on November 5th, 2015.

- APMO: Franciszek Jazwieck; Wspamnienia (Dreams, written in the camp), vol.32, 84-85. Also cited in Szymanska, Portret, 95, In Sybil Milton, "Art in the Context of Auschwitz", in Art and Auschwitz, ed. by David Mickenberg, Corinne Granof and Peter Hayes, (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2003), p. 64.

Another purpose that art served was to record secret SS medical experiments and racial hierarchy in Birkenau. One artist whose work served this purpose was Dinah Gottliebova's. Gottliebova was forced to draw portraits of Sinti and Roma by Mengele, the senior SS physician in Birkenau, for a future publication about the racial hierarchy and the experiments that he would perform on them. Gottliebova's assignment in the Sinti and Roma camp continued until they were all murdered in the Birkenau gas chambers.

Gottliebova was taken daily to Mengele's office from the Theresienstadt Family Camp and, after March 1944, from the women's camp, where she and her mother had been moved to. She was given cardboard, brushes, watercolors, and two chairs to paint portraits of Sinti and Roma subjects used in Mengele's genetic and medical experiments. She later recalled that she had painted around ten portraits of the Sinti and Roma; in them, we can grab the humanity of her subjects, she portrayed them showing that they were human beings and not mere objects on whom cruel experimentations were performed.

Dina Gottliebova arrived at Auschwitz from Terezin and was assigned to the Theresienstadt Family Camp.

Freddy Hirsch, who ran the children's block asked her to paint a mural to cheer up the children in the children's bunker.

She recalls that she intended,

"to make it look like we are in a Swiss Chalet...with flowers and flower pots on it and we're looking out at the beautiful meadows and maybe some cows and sheep...and then I noted that all the kids were standing around me, behind me, so I turned around and I asked them if they have any special need what to put in that meadow and they said "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs" and that was a very surprising answer but since I had seen the picture seven times before, even while Jews were not allowed to go to the movies anymore with my star in my pocket, I had memorized everything down to the soft shoes, the way they moved and everything. So I made a painting... and the kids loved it. ..., I made almost all the dwarfs standing around some of them were clapping and that's what the kids like."

1

Gottliebova's wall paintings and the pictures she was making for SS members were seen by Franz Lucas, the SS physician for the Theresiendstadt Family Camp and the Sinti and Roma Camp in Birkenau.

"...and (Lucas) took me to Mengele. Mengele was trying to photograph Gypsies then and Lucas told him 'Here is the painter I told you about' and Mengele said 'Do you think you can paint as accurate as a photograph and get the colors right because in photography the colors come out to they are not correct' and I said 'I can try'."

2

Mengele claimed that photographs didn't capture the skin color of the Sinti and Roma (Gypsies) as it was. He wanted to prove by their skin tone that they were genetically inferior to the Aryan race. Before accepting the task, Dinah Gottliebova told Mengele that she would only do it if he would spare her mother from the gas chambers. She threatened suicide otherwise. She told him "I'm not staying here without my mother alive" Mengele said "What's her number?

In her interview made by USC Shoah Foundation she refers to one of the women from her Sinti and Roma portraits, whom she befriended,

"Then I went to get another girl and that was Celine, she was French, and we became friends, we started talking. She had this, not just sad but totally wistful empty look about her and I said 'Are you sick? Is something wrong?' and she said 'My baby died' I said 'How old was your baby?' She said 'Two months old. I couldn’t feed him. I didn't have any milk. It starved to death, it's gone.' We were hardly able to speak, she didn't speak much German and I didn't speak any French at that time but we did get things across. And then I asked her if I can do anything for her because she looked sick and she said 'Well I have terrible diarrhea I can't hold that black bread I can't eat it, everything that I ate so far just goes right out of me'. So the next time Mengele asked someone to bring some lunch for me, to bring some food, I said could I have white bread please, so I got white bread everyday which I gave to Celine and it helped her a little...I painted her, it occurred to me that she was so beautiful in a fine delicate way...she was like a porcelain doll and I thought with the blue scarf she wore I will make her look like a Madonna and I took the scarf and untied it and I draped it around her head and then Mengele came in and he said yeah but I want the ear, and he took the scarf and put it behind her ear so she had to tie it back again and that's why she's the Madonna with the ear...then there was a little (Sinti and Roma) boy that I also painted later...I remember (that I painted) about 11, so I would say 10... the entire Gipsy camp was gone and I found out that they were all gassed."

3

Dinah Gottliebova-Babbitt's biography

Annemarie Dinah Gottliebova was born in Brno, Czechoslovakia in 1923. She started studying art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague. When the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia she was forced to abandon her art classes. In January of 1942 she and her mother were sent to the ghetto and transit camp of Theresienstadt. In the fall of 1943 they were both transferred to Auschwitz with more than 4,000 other Jews.

On January 19th, 1945 she was sent in a Death March to Ravensbruck camp for women, from where she and her mother were liberated on May 5th, 1945.

In Paris, after the war in a job interview, she met an American cartoon animator, Art Babbitt who reluctantly had worked on Disney's "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs". They eventually got married and moved to Hollywood, California, where she worked as an assistant animator for different companies on films and cartoons.

After nearly thirty years since the end of the war, she got to know about the fact that some of the water-colors she had painted, of the Sinti and Roma by command of Josef Mengele, in Auschwitz, had not been destroyed. They had survived and had been bought by the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. The moment the Museum's staff was able to identify Mrs. Gottliebova as the same person who had signed the watercolors as "Dinah 1944" and they found her address, they made contact with her, informing her on the existence of the works she had created in the camp. In January 1973, she went to Poland to see them.

In the mid 90's she began a quest to have her paintings returned to her. The museum claimed that they were "...a unique document and piece of evidence, having the biggest meaning, significance and impact in the place of their creation."

She died in 2009, at the age of 86.

- From the testimony of Dina Gottliebova-Babbitt Jewish Survivor, USC Shoah Foundation

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum website http://auschwitz.org/en/ accessed on November 5th, 2015.

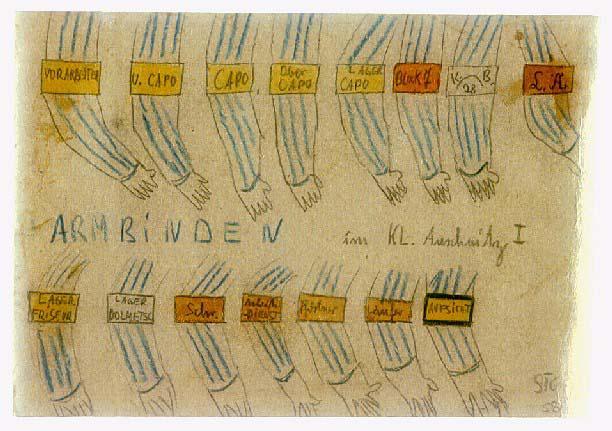

When he was liberated on April 11th, 1945 from Buchenwald concentration camp, Thomas Geve, who was fifteen years old at the time, found some scraps of paper the SS had left behind and asked for some colored pencils. He began to document the details of everyday life in the concentration camps he had been in, including Auscwhitz, with the seven colors he was given. His goal was to somehow explain to his father what he had been through. His father had fled Germany in 1939, and had gone to England with the intention of also bringing Thomas and his mother there. In the meantime, the Second World War began with the invasion of Poland, in September 1939 and Thomas and his mother weren't able to leave the country anymore.

Eventually they were both taken to Auschwitz where Geve's mother was murdered. In Auschwitz Thomas Geve was able to work as a bricklayer. He drew compulsively and produced a series of seventy nine drawings.

Thomas Geve's biography

Born in Züllchow as Stefan Cohn, in 1929. In 1939, he moved with his family to Berlin. His father immigrated to England but Stefan and his mother were unable to join him. After the closure of the Jewish schools, he was forced to work in the Jewish cemetery at Weissensee. His mother was put to work making alterations in German Army uniforms. In June 1943, he and his mother were transported to Auschwitz, where they were separated, and his mother was murdered. Stefan was assigned to a bricklaying commando. With the approach of the Red Army in January 1945, he was evacuated on a death march to Gross-Rosen and then to Buchenwald. In April he was liberated by the American Army. Upon his liberation, he drew 79 works depicting his personal annals during the war. He was transferred to an orphanage in Switzerland, and then to England, where he reunited with his father. He immigrated to Israel in 1950, and after army service as an engineer officer, studied and worked as a construction engineer. He published his memoirs in the book Youth in Chains.

These paintings are part of the series Stefan painted immediately upon liberation, in order to be able to relate his wartime annals to his father.

"On January 27th, 1945, Red Army soldiers liberated Auschwitz-Birkenau. As the Soviet Army was approaching the Auschwitz vicinity the Nazis started retreating quickly from the camp In Birkenau. Most of the remaining camp's prisoners; men, women and children, 58,000 in number, mainly Jews, were evacuated in brutal death marches in the direction of Germany and Austria.

In Birkenau the soldiers found the corpses of 600 prisoners who were murdered by the Nazis shortly before the evacuation. Some 7,650 prisoners, mostly sick and in a state of collapse, remained alive in the camp. In the storehouses, the Red Army soldiers found hundreds of thousands of sets of clothing, tens of thousands of pairs of shoes, and 7.7 tons of human hair in paper bags packed for transport.

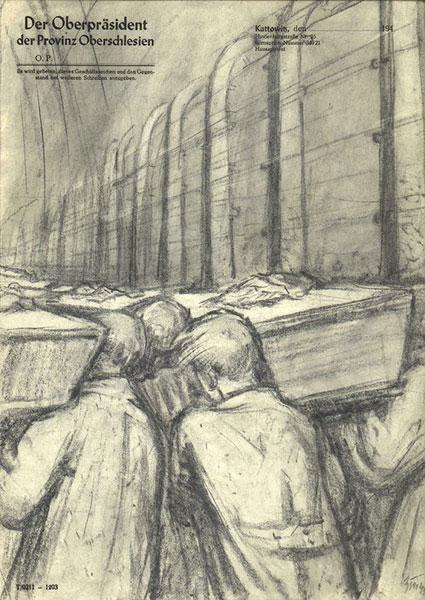

With the USSR entering the war in June 1941, the Jewish artist, Private Zinoviy Tolkatchev volunteered to join the front. In the autumn of 1944, he was sent to serve as an official artist of the Red Army in the Political Department at the First Ukrainian Front.

At the end of January 1945 he accompanied the Nazi Crimes Investigation Commission to Auschwitz, literally hours after the entrance of the Red Army into the camp. Tolkatchev, seized by the urge to capture the scenes and the voices, entered a spiritual whirlwind. In a frenzy and he immersed himself in painting the horrifying scenes he witnessed. In the absence of drawing paper he entered the camp's former headquarters and took stationary with bold black letters: Kommandatur Konzentrationslager Auschwitz; I.G. Farbenindustrie Aktiengesellschaft; Der Oberprasident der Provinz Oberschlesien. The typography becomes an integral part of the composition and the image of the Nazi oppressor. The fact that on these same pieces of paper were written, just a few days earlier, orders of extermination, endow them with a tragic power that causes one to shudder.

He obsessively drew sketches of what he saw. Next to the sketches he added densely written lines with the testimony of the few survivors able to utter words. And he jots repeatedly –'to remember, not to forget'."

In the words of artist Private Zinovii Tolkatchev who arrived at the gates of Hell in Red Army uniform,

"I did what I had to do; I couldn't refrain from doing it. My heart commanded, my conscience demanded, the hatred for fascism reigned."

Zinovii Tolkatchev's biography

(1903-1977)

Born in the town of Shchedrin in Belarus. He was active in the Communist youth movement and later in the party. In 1928, Tolkatchev studied art in Kiev and in 1929 held an exhibition on the death of Lenin. In the thirties, he illustrated books, including works by Gorky and Sholem Aleichem, and exhibited the series, “The Shtetl”. From 1941-1945, he served as an official artist in the Red Army. In the summer of 1944 he was attached to the Soviet forces at the front after the liberation of Majdanek, and afterwards to the forces liberating Auschwitz. In these camps he painted and drew series of artwork depicting the horrific scenes he witnessed in these camps. These series were exhibited throughout Poland at the close of the war. He died in Kiev in 1977.

- Yehudit Shendar, Senior Curator, Yad Vashem Art Museum, Private Tolkatchev at the Gates of Hell, Majdanek and Auschwitz Liberated: Testimony of an artist. Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, 2005.

- Ibid. p.5.

- Learning and Remembering about Auschwitz-Birkenau (Lesson Plan)

- Auschwitz album (Lesson Plan)

- The transport (Lesson Plan)

- Liberation and survival (Lesson Plan)

- Women in Auschwitz (Ceremony)

- Development of Auschwitz (Interactive Timeline)

- Archival data preservation in the State Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau in Oświęcim - How many people can we commemorate by name?

- The Auschwitz Album

- The Stories of Six Righteous Among the Nations in Auschwitz

- 19 km from Auschwitz - the Story of Trzebinia

- Private Tolkatchev at the Gates of Hell - Majdanek and Auschwitz Liberated: Testimony of an Artist

- And These are Their Names... - Identifying the Death March Victims Buried in a Mass Grave in Poland

- Child Survivors at the Liberation of Auschwitz – 27 January 1945

- Until The Last Jew... Until The Last Name