Grades: 5 - 6

Duration: 1 - 1.5 hours

This age-appropriate lesson plan is suitable for pupils in grades 5-6, and enables children to relate to an individual victim in a world of hardship and difficult dilemmas.

This lesson plan highlights the personal story of Uri Orlev, a Holocaust survivor, who became a writer and translator in Israel. The story, based on his book “The Sandgame,” is told from Uri’s viewpoint as a child. His dreams, hopes and ambitions are described, along with his experiences in ghettos, hiding, and the death of his mother.

Background Information

Uri Orlev was born Jerzy Henryk Orlowski in Warsaw, Poland in 1931. His nickname was Yurik. As a small child, he initially did not know he was Jewish. When the Second World War broke out with Nazi Germany in September 1939, his father was drafted into the Polish army. In November 1940, Yurik and his extended family were forced into the Warsaw Ghetto. After working for several years in a factory in the ghetto, his mother became ill and died in January 1943. After his mother’s death, his aunt, Stefa, looked after him and his brother Kazik.

In February 1943, Yurik and his brother were smuggled out of the Warsaw Ghetto and were hidden in the Polish section of Warsaw. At the time of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in April, Uri and Kazik had been in hiding for two months. Fearing the Nazi search patrols, the brothers were then moved to a solitary country house and hidden in a dark cellar for many weeks, which they were only allowed to leave at night. In the summer of 1943, together with their aunt, Yurik and Kazik were sent to Bergen-Belsen, a Nazi concentration camp, where they were incarcerated for about two years. After liberation, their aunt managed to provide them with entry permits to Israel. Eventually, the brothers settled at Kibbutz Ginegar.

It is suggested that excerpts from Orlev’s book be read with the students. Other sections of Orlev’s story are to be recommended at the discretion of the educator.

Childhood Before the War

Student/Teacher Reading:

“I was born in 1931. My father was a doctor. My first ambition was to be a streetcar driver. I wanted to lounge by the throttle and ring the tinkling bell by pressing an iron pedal with my foot to warn pedestrians, wagons, horse-drawn carriages, and automobiles of my approach. Until one day it struck me that the policeman who stopped and started traffic with a wave of his hand was even more powerful. From then on, I wanted to be a policeman [..]

A short while after my younger brother was born, we moved to a village in the suburbs because my mother wanted to get away from the dirt, germs, and brawling of the city. We now lived in half of a new two-family house, and my father traveled to his clinic in Warsaw every day and came home late a night. The only day he spent with us was on Sunday. In summer, he took me on the river in a rowboat or kayak and in winter we cross-country skied. I liked to get up early in the morning to see him doing his exercises...when my father was dressed I brought him his shoes, and then we sat down to breakfast.”1

Discussion Question

- How would you describe Yurik’s childhood before the war? Cite examples from the text.

Shortly after Yurik’s brother, Kazik, was born, Yurik’s parents moved from Warsaw to a village, hoping to get away from the city. Yurik’s father, Maximilian Orlowski, was a doctor, and his mother Zofia assisted him at his clinic in the city. Yurik enjoyed reading books and playing adventure games with his brother. When the two reached school age, the Orlowski family returned to their Warsaw home. In 1939, following the outbreak of World War II, the Nazis invaded Poland and conquered the capital.

"And Then the War Broke Out..”

Student/Teacher Reading:

“I had read a lot of books before the war. [..] My favorites were war and adventure books. I liked to read about heroic grown-ups or children who went through all kinds of ordeals until everything turned out all right. Books with sad endings left me feeling queasy long after I had finished reading them. [..] The more I read, the more I envied the heroes I read about. Why didn’t anything ever happen to me? And then the war broke out, although even then it took me a while to realize what was happening to me.”2

"Have you ever woken up in the morning and prayed for something, anything-a fever or not-too-bad storm, or even a little war - that would allow you to go back to sleep? It was as if my prayer had been answered.”3

“The one thing my mother didn’t think of was air raids, after a month of which we found ourselves fleeing a building that had gone up in flames. You've probably seen such films in the movies: fire shooting out of the windows, timbers cracking from the heat, walls crashing down, screaming people jumping from upper stories. We ran down the street, my mother holding our hands. The sparks flying though the air kept catching my brother’s jacket, and my Aunt Mela ran after him putting out the fires. [...]

Once the burning buildings were behind us, we wandered the dark streets knocking on the gates of houses. Nobody let us in, because no one wanted a flood of refugees camping out in their backyard or stairwell...”4

Discussion Questions

- How were wars portrayed in Yurik’s books? How did Yurik imagine them?

- How does Yurik remember the outbreak of the Second World War?

Using his imagination and after reading many adventure stories, Yurik tried creating a kind of safe haven that would protect him from the traumatic experience of war and the inevitable changes in his life. Point out the differences between fiction and reality. Yurik, who had read many war and adventure stories, had secretly wished for an adventure of his own. However, suddenly he faced the brutality of bombings and death around him.

Life in the Ghetto

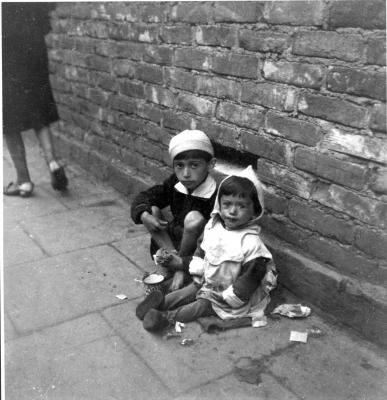

With the outbreak of the Second World War, Yurik’s father was drafted into the Polish army. At the end of 1940, the nine-year-old was forced into the ghetto along with his family. The Warsaw Ghetto was a cordoned-off area that housed some 450,000 Jews in extremely cramped conditions. The situation in the ghetto was extremely harsh: Many Jews succumbed to disease and illness, and children were particularly at risk. In an effort to cope with this difficult new reality, Yurik and his brother made up stories.

Student/Teacher Reading:

“The Germans crammed half a million Jews from Warsaw and the vicinity into the ghetto and built a wall around [it]. Hunger and disease spread there. [..] My mother gave me a sandwich everyday for my morning snack. [..] I always saw plenty of dead bodies that had been laid out on the sidewalk before dawn and covered with newspapers. You could tell from the length which were children. On my way back from Miss Landau's they were gone.

Some people were so hungry that they became known as “snatchers.” The snatchers snatched anything that looked like food and stuffed it in their mouths before you could grab it back. One day one snatched my sandwich.”5

“One day I made up a story that everything that had happened - the war, the ghetto, the Holocaust - was a dream. I was the son of the emperor of China, and my father, the emperor, had ordered my bed placed on a large platform and surrounded by twenty wise mandarins (they were called “mandarins” because each had a mandarin orange attached to the top of his hat.) My father had ordered them to put me to sleep and make me dream what I did so that when I became emperor myself one day, I would know how terrible wars were and never start any [sic]. My brother never tired of this story. Whenever anything scary or dangerous happened to us, he would ask for it.”6

Discussion Questions

- What role do imagination and role-playing serve in Yurik’s existence in the ghetto?

- What can we learn from these excerpts about Yurik’s relationship with his younger brother?

The day-to-day struggle and intolerable living conditions of the ghetto increased Yurik’s reliance on imagination, which helped him make his conditions more bearable. As the elder brother, Yurik shared this world of imagination with his brother, and in doing so attempted to protect him. Yurik was only eleven-years-old, and was already forced to take responsibility for his younger brother Kazik. It was common during the war for children to assume adult roles. In many cases, parents were either forced to work long hours or were deported and thus could not comfort youngsters. In view of these circumstances, children became adults almost overnight.

The following two excerpts focus on Yurik’s daily life in the ghetto:

Student/Teacher Reading:

“From my aunt’s, I went to my grandmother, who felt sorry for me and gave me a zloty to take a rickshaw home. I liked traveling by rickshaw, especially if it was an upholstered one, with little bells and ornaments, the kind my mother warned me not to take, since it might have typhus-carrying lice in the upholstery. Dozens of people died of typhus in the ghetto every day, and only the rickshaws with wooden seats were safe. The upholstered ones made me feel like a king, although I was careful to get off far enough away from my home to keep my mother from seeing.”

“One day I felt sorry for the skinny boy outside our house who kept crying “a piece of bread.. a shtikele broyt.. A piece of bread.” No one ever took pity on him. Maybe there were too many children like him. I stood a way off, held out my hand, and said in a loud voice: ‘Give something to a poor little boy… give something to a poor little boy.’

To my astonishment, I received lots of money. One man stopped and said to his wife: “And such a well-bred little fellow. Just look what we’ve come to!” Before long I had a large sum. I was sorely tempted to enter the toy store across the street and buy the jackknife my mother refused to get me because she was afraid I would hurt myself or my brother with it. In the end, though, I decided this would be cheating. It wasn’t what I had been given the money for. And so I handed it all to the beggar boy, went home, and proudly told my mother what I had done. She gave me a severe look and asked: “Did any of the neighbors see you? All I need is for them to think I’m sending you out to beg. Dr. Orlowski’s son, what a disgrace!” I promised her never to do it again, and from time to time she gave me a coin to give the boy.”7

Discussion Questions

- What can we learn from these excerpts about Yurik’s moral choices? Refer to the decisions he makes.

- How does Yurik’s mother respond after hearing about his actions?

In the first section, Yurik engages in typically childish behavior, riding a rickshaw in order to “feel like a king,” despite his mother’s warnings. In contrast, the second section describes a more mature Yurik, and a deeper understanding of the harsh reality surrounding him. He overcomes his urge to buy toys in favor of assisting a child in need.

Deportations from the Ghetto and Life in Hiding

In 1942, the Nazis began deporting Warsaw Jews to the camps, most of them to the Treblinka extermination camp. Many houses stood empty, a grim testament to their previous inhabitants. Meanwhile, the remaining Jews in the ghetto were employed in workshops and attempted to sustain themselves under worsening conditions. The few remaining children lived in constant fear of being deported, and were forced to hide to avoid capture. Each day, while their mother was working in a factory, Yurik and Kazik would hide until she returned. Eleven-year-old Yurik described the prevailing fear in hiding:

Student/Teacher Reading:

“I hated having to hide and listen to them search for us. It would scare me to death. It scared me even when we were together with the adults. We would sit sometimes all huddled together in an attic or a basement, locked in a closet or in a cove behind a stone wall. We couldn’t make a sound, and all we would hear was the sound of the people searching, their footsteps, their knocking on the walls. Will they find us? Or won’t they? We couldn’t cough or sneeze, and just then the throat would tingle or the nose would itch.”8

“..We had a game that we played. In it I was Tarzan, Commander of the World, and my brother was either my chief enemy, if we were at war, or the friendly head of the neighboring country, if we were at peace. Each of us had a large army, and during the six years of the real war, we fought our own imaginary one.

How we conducted it depended on the circumstances. If it was night or we were hiding in the dark, we fought by talking, each announcing his army’s moves and countering the other’s. If it was day and we could play on the floor, we fought with toy soldiers, chess pieces, and huge stacks of playing cards that I had brought back from various apartments.”9

Discussion Question

- What difficulties did Yurik and his brother face? How did they try to cope with them?

Allow students to discuss their impression of the brothers’ day-to-day existence. As Yurik focuses on the war games the two played, the greater context is of a life in hiding, with a constant fear of being discovered.

“What Will Happen to the Children..?”

At this stage, Yurik and Kazik’s life became especially difficult and dangerous. After a prolonged period of hard labor and intolerable living conditions in the ghetto, their mother Zofia fell ill. She was hospitalized in the ghetto hospital and eventually died.

Student/Teacher Reading:

“My Mother fell ill [..] She was taken to the Jewish hospital in the ghetto. We stayed with Aunt Stefa. The night before my mother lost consciousness she was lying in bed and her head was hurting her more than usual. They thought I was asleep and were talking between themselves. My mother said:

“What will happen to the children if I don’t pull through?” “Don’t worry, Zofia,” said Aunt Stefa, “I will take care of the children.” Then my mother said: “Stefa, keep them with you always, for better or worse.” Aunt Stefa made this promise to my mother and was as good as her word. [..] As long as my mother was alive, I thought or felt, that an invisible presence was watching over me. When she died I lost faith in it, but after a while she herself became the mysterious spirit hovering over my brother and me.”10

Discussion Question

- How did Yurik try to cope with his mother’s death?

Following the death of his mother, Stefa smuggled Yurik and Kazik to the Polish area of Warsaw, and they were later hidden in a dark cellar for several weeks. In 1944, Yurik and his brother were transferred to the Bergen Belsen concentration camp in Germany. Later, their aunt managed to obtain travel documents allowing them to emigrate to pre-state Israel. From that moment on, the brothers would be on their own. Yurik (Uri) recalls his aunt’s words before they parted.

Student/Teacher Reading:

“’Yurik,’ she said, ‘listen to me carefully. Tomorrow you’re not going to have an aunt any more to explain everything to you. In this bag I’m putting the food for the rest of your trip. All the clothes are in Kazik’s bag. [..] I’m putting the sandwiches for the first day of your trip right here; make sure you don’t sit on them. Where did you put your notebook? Whatever you do, don’t lose it. Yurik, you have to be an adult now, do you understand? [..] Do you promise? And wear your woolen sweaters [..]

And don’t you dare tell your true ages [..] You were born in ‘thirty five and you in ‘thirty three. Remember, or else they’ll send you off to work and won’t have any time for school. You’re not like other children, you know. You lost six years in the war.’ Kazik cuddled up to her wordlessly.”11

Discussion Question

- What instructions did Aunt Stefa give the children? What was she preparing them for?

Stress to the students that Yurik and Kazik are orphans. Until this point, their Aunt attempted to care for them as best as she could. Now, however, they would have to confront the difficulties of life without a parental figure. As the older brother, the instructions were aimed mostly at him, and he had to carry most of the responsibility, though he was only thirteen years old at the time.

Arrival at the Kibbutz

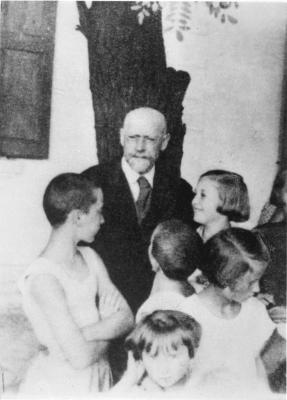

After a long journey, the Orlowski brothers reached Israel, settling in Kibbutz Ginegar (collective community). In the kibbutz, the boys were called by their new Hebrew names – Yurik became Uri, and Kazik became Yigal.

Student/Teacher Reading:

“The kibbutz was an odd place in which everything was shared by everyone. The night we arrived, my brother and I were brought to a lawn outside the dining hall and everyone who spoke Polish came to hear me tell about the war. I spoke for hours, and no one moved or said a word. All you could hear were the crickets, and sometimes the moo of a cow or the bark of a distant dog. [..] The kibbutz became my home, and the few years it took me to finish high school there were like a second childhood for me.”12

Discussion Question

- How can Yurik's arrival at the kibbutz be considered a turning point in his life?

It’s important to point out that despite Orlev’s many painful experiences after the war, he fondly describes the night he told his story to the kibbutz members.

Yurik Orlowski formally changed his name to Uri Orlev. He married, and today has four children and two grandchildren. He became a writer, and has written many books, including books for children.

Student/Teacher Reading:

“I don’t know if writing about the past helps me to get over it. What I do know is that there is no grown-up way to talk, tell or think about the things that happened to me. I have to remember them as if I were still a boy, with all the strange details, some funny, and some moving that childhood memories have and that children have no problem with.”13

Conclusion

Yurik’s childhood, full of imagination, freedom and leisure time, was suddenly cut short with the outbreak of the Second World War. Life in the ghettos was difficult - especially for children. They were forced to endure harsh conditions in the ghettos, and often suffered from the absence of adult figures to guide and protect them. In addition, children had to come to terms with being torn apart from family and loved ones. With the help of his rich imagination, Yurik tried and overall succeeded in overcoming these difficulties. The stories he created served an anchor for Yurik and Kazik during the Holocaust. This same imaginative spirit inspired Yurik/Uri, who later in life became a writer, and thus managed to impart his story, on future generations.

- 1.Uri Orlev, The Sandgame [English Edition], Ghetto Fighters House, 1995, p. 5, 7.

- 2.Ibid., pp. 18-19.

- 3.Ibid., p. 17.

- 4.Ibid., pp. 19-20.

- 5.Ibid., pp. 22-24.

- 6.Ibid., pp. 31-32.

- 7.Ibid., pp 24-26.

- 8.Uri Orlev, The Sandgame [Hebrew Edition], Keter 1996, p. 32.

- 9.Uri Orlev, The Sandgame [English], pp. 28-30.

- 10.Uri Orlev, The Lead Soldiers, Peter Own Limited, London 1979, pp. 215-216.

- 11.Uri Orlev, The Sandgame [English], pp. 55-56.

- 12.Translaed from the Hebrew text.

- 13.Uri Orlev, The Sandgame [English], pp. 55-56.