Testimonies and other primary source materials, highlighting the voices of those who lived during the Holocaust, augment the photographs in the Auschwitz Album. In viewing photos from the album, we can trace the path that Nazi victims were forced on from the moment they boarded the trains up to their registration as prisoners for forced labor, or their deaths.

Introduction

IntroductionIn this lesson we have chosen photographs that focus on the four stages that most victims endured at Auschwitz-Birkenau:

- Arrival

- Selection

- Transformation into a prisoner (for the minority of Jewish arrivals)

- On Their Way to Death in the Gas Chambers (for the majority of Jewish arrivals)

Opening Classroom Discussion Questions

- What was Auschwitz? What does it symbolize? What happened there?

Notes to the Teacher:

It is important to emphasize that Auschwitz was both a concentration and extermination camp. It has become the primary symbol of the Holocaust because of the large number of those murdered there, the fact that Jews were sent there from all over Europe, and because of the industrial character of the killing process.

- Has anyone visited the site? If so, what can you tell us about it?

Notes to the Teacher:

Today Auschwitz is a museum and a memorial, therefore when one enters the site today, one will not see the place as it was 60 years ago. Some buildings were preserved and others are gone; there is grass, and so on.

- What photographs of Auschwitz have you seen before? Describe them. How does it make you feel to look at these pictures?

- Do you think that people from different nationalities perceive these photographs in different ways? Explain your answer.

- Why is it important to differentiate between Auschwitz then and now?

The Story

Lili Jacob and her family arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on May 26, 1944. With them on the train were several thousand Jews from Lily’s town and from other towns. Look at the photos documenting their arrival. (See photographs 1-4 below)

This is Siddy Miller (Photgraph 3). She has just disembarked from the train. What do you think she knows about the place where she just arrived? What do Lili’s brothers know (Photgraph 2)? What do her grandparents understand (Photgraph 1)?

While we cannot know for certain what people felt simply by looking at a photograph, other sources can shed light on this and provide us with tangible responses.

Other sources include:

- Last letters and notes documenting the thoughts and feelings of Jews en route to the death camps. These letters, which were thrown from trains and found throughout Europe, help us expand our knowledge regarding the experience of Jewish victims. Some letters were donated, while others were preserved, by relatives, neighbors, and friends. Many of these last letters have been gathered into a collection and published by Yad Vashem.

- Testimonies of those who were among the deportees to the camp.

It is important to emphasize that victims usually did not realize that they were being taken to be murdered, and their whole experience is told from this prism.

The Journey

The JourneyThe Journey to Auschwitz-Birkenau

Last Letters:

The following note, thrown from a transport to the Auschwitz extermination camp, was written by an unidentified Jew to his family still living in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Plonsk, December 16, 1942

Please toss the note in the nearest mailbox. It is now morning. We are in the railroad car with the whole family. We are leaving with the last transport. Plonsk is cleansed [of Jews; German expression]. Please go to the Bam family, on 6 Niska and send them regards.

Yours truly,

This letter, thrown from a train that brought a group of Jews to Auschwitz, was written by a Jew named David to his family in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Legionowo, December 16, 1942

(Additional payment 18 groshen (Polish currency)

Warsaw)

Nalewki [street] 47/19

Please kindly toss this into a post box. Today we left Plonsk, our whole family, and all the Jews traveled. Be aware, that we are traveling to a wedding *

Majd találkozunk,

Dávid

*This means: to annihilation. In order to overcome German censorship, Jews used certain words or expressions, sometimes in Yiddish or Hebrew, to express their real thoughts and intentions.

Personal Testimonies

Cecilie Klein-Pollack

Born in 1925 in Jasina, Czechoslovakia (a region under Hungarian rule at the time), Cecilie was on the train with Lili Jacob. From Auschwitz she was taken to Holleischen camp in the Sudeten region and was liberated there by the British Army. She married in August 1945 and had 3 children. She now lives in the United States.

We, were about 80 at least in a box car. This was for cattle. It wasn’t a regular train. It was a cattle train, that we could almost suffocate. […] and we got — there were pails for, for bodily functions. And they would, they stopped a few times so what was, they, they told my brother in law.... My brother-in-law was with us, you know my sister, my brother-in-law and their little boy Danny and my mother and me. We were all together on the train because my sister was taken away from Jasina, so she was not with us together. […] And so finally when it stopped, when the train stopped, they, they opened up the door; and they told my brother-in-law to take out the pails, to throw out the pails and to bring water. In the same pails they brought water, and we had to drink this water. […] and they, they warned him if anybody escapes then we will all be shot. […] And my mother was, was — we, were trying just to be as close together and to hug and to and to tell our last — we didn’t know what that we are going we didn’t expect though that we are going to be killed because I knew, our mind could not comprehend that anybody is going to kill little children.”

Livia Lieberman

Born in Oradea, Transylvania in 1922. After months of torture by the Hungarian police in the ghetto where she was held, she was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau in May 1944.

They loaded 70–75 people into a small boxcar, in the intense heat without a drop of water. The windows were closed; the boxcars sealed. The trains made their way slowly; the journey went on forever. For those locked inside the death cages, it seemed as if the torture would never end. Not one of the Hungarian guards showed the slightest semblance of mercy or desire to help. On the contrary, whenever they could, they added to the suffering. Those who were suffocating from lack of air begged them to open the windows for a few minutes. Those antisemitic policemen would only do so after they had been given a bribe — a gold watch for 5 minutes of air to breathe. Screams announcing that people had died from suffocation and dehydration could be heard from other boxcars. Little infants were crying from hunger, thirst, and lack of air.

The horrible journey to the Land of the Death, to the crematorium in Auschwitz, lasted 4 days.

Eliasz Skoszylas

Born in Szemeisieza in 1916, Eliasz arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943 from the Będzin Ghetto. From there he was taken to the sub-camp Gintergrube. In the final months of the war he worked at digging defensive ditches in Grietenberg.

Words cannot convey the tragedy that took place then. There was indescribable chaos. They herded us like cattle while raining down curses and shouting. The groans of those who were trampled mixed with the cries of the children and the sobbing of the women. Yet, to our sorrow, the wailing made no impression on the consciences of those beasts in men’s clothing who were totally impervious as they carried out this murderous process. They threw us into the boxcars like bunches of rags. Without food, suffering the terrible stench and lack of air to breathe, we were dragged along, thirsty and hopeless. It seemed as if this journey was lasting forever.

Imre Kertesz

Born in 1922 in Budapest, Hungary. In 1944, he was deported to Auschwitz and, three days later, to Buchenwald. After the war he worked as a journalist and translator of German literature and philosophy. Kertesz received the Nobel Prize for literature in 2002.

Dawn outside was cool and fragrant. A gray mist hovered over the wide fields, and then unexpectedly, but just like the sound of a trumpet, a thin sharp red ray appeared from behind somewhere, and I understood that I was seeing the sunrise. It was beautiful and quite interesting: at home I usually slept during this hour. I also spotted a building, directly to my left, an abandoned station or perhaps the forerunner of a larger station. It was tiny, gray, and entirely deserted, with small, closed windows and with that ridiculously steep roof that I had been seeing ever since yesterday. Before my very eyes it solidified into a concrete outline in the misty dawn, changing from gray to lilac, and then all at once its windows glistened red as the first rays struck them. Others observed this too, and I recounted it all to the curious. They asked if I could see a name above it. I did: namely, I saw the words in the early light on the narrower side of the building facing in our direction under the roof. Auschwitz – Birkenau was what I read, written in the fancy ornate letters of the Germans, with the two words connected by a double-curved hyphen. I for one canvassed my geographic knowledge in vain; others proved no wiser that I about the place.

Primo Levi

Born in Torino, Italy in 1919. In January 1944, at the age of 24, he was captured by the Italian Fascist Militia and sent to Auschwitz. On January 27, 1945, after the liberation of the camp, he returned to Italy. Author of many books on Auschwitz, which became classics, among them, If this is a man. In 1987, he committed suicide.

The doors had been closed at once, but the train did not move until evening. We had learnt of our destination with relief. Auschwitz: a name without significance for us at that time, but at least implied some place on earth...

Through the slit, known and unknown names of Austrian cities, Salzburg, Vienna, then Czech, finally Polish names. On the evening of the fourth day the cold became intense: the train ran through interminable black pine forests, climbing perceptibly. The snow was high.... During the halts, no one tried anymore to communicate with the outside world: we felt ourselves by now “on the other side”....”

Primo Levi If This Is a Man, (New York, Orion Press 1958), 8–10. old.

- After examining the pictures and reading these testimonies, students should address the following questions, either in a class discussion or in small groups. Ask your students to answer the following four questions:

Notes to the Teacher:

- What are the conditions described in the testimonies?

- What are the smells and sounds?

- What do these testimonies reveal about the concept of time?

- Do the deportees know anything regarding their destination?

Terrible physical conditions included overcrowdness, lack of air, no privacy for toilets, the same pails for drinking and excrement. Therefore, the smell was horrible. The sounds were cries of people over their dead, and of children. Sometimes, people also heard the soldiers’ shouts. Regarding time, “it seems as if the journey was lasting forever.” There was no knowledge regarding their destination. It appears that only a few knew their destination. As Imre Kertesz and Primo Levi specified, the name “Auschwitz” had no meaning for them; moreover, the lack of meaning gave them a good, secure feeling.

The previous testimonies were from people who were on the trains. The following is a testimony from a different angle — that of a forced laborer who witnessed trains arriving. Tadeusz Borowski was a non-Jewish Polish prisoner, caught for being a resistance activist. He worked in “Kanada Kommando,”

“’The transport is coming,’ somebody says. We spring to our feet; all eyes turn in one direction. Around the bend, one after another, the cattle cars begin rolling in. The train backs in to the station, a conductor leans out, waves his hand, blows a whistle. The locomotive whistles back with a shrieking noise, puffs, the train rolls slowly alongside the ramp. In the tiny barred windows appear pale, wilted, exhausted human faces, terror-stricken women with tangled hair, unshaven men. They gaze at the station in silence. And then, suddenly, there is stir inside the cars and pounding against the wooden boards. “Water! Air!” — weary desperate cries.”

- Last Letters from the Shoah, edited by Zwi Bacharach (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem and Devora Publishing, 2004), pp. 92, 93.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Interview with Cecilie Klein-Pollack, May 7, 1990, RG-50.030*0107.

- Livia Lieberman, Yad Vashem Archives, M49 E/80.

- Eliasz Skoszylas, Yad Vashem Archives, M49E/227.

- Imre Kertesz, Fateless (Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1992, 1996), p. 56.

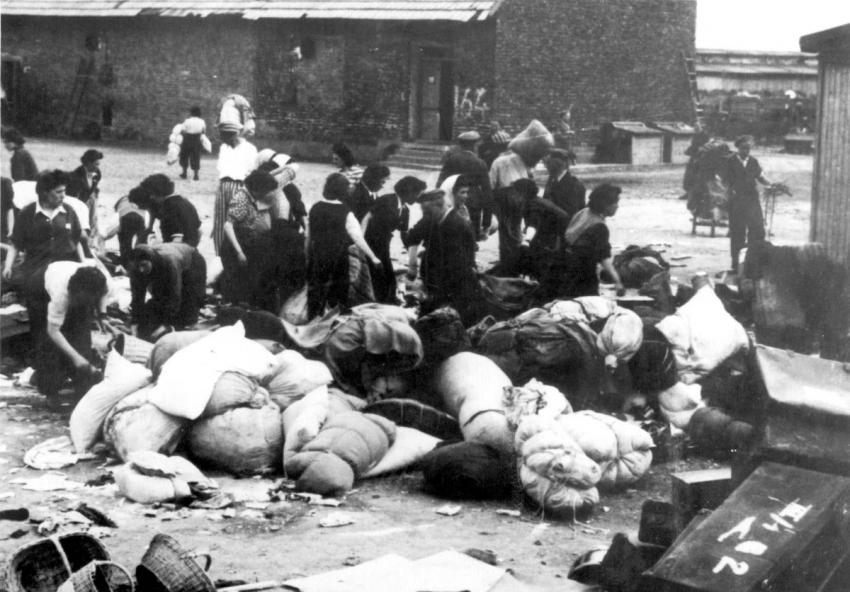

- When the trains arrived, the victims were ordered to leave their belongings on the ramp. The “Kanada Kommando” were forced laborers who gathered these possessions, sorted and stored them in special warehouses in a subcamp called “Kanada” because of the wealth associated with that country. From the Kanada sub-camp, the valuables were shipped to Germany to enrich the Third Reich. This forced labor unit was organized in the summer of 1942 in Auschwitz I. In January 1943, the men of “Kanada” were moved to Birkenau. The unit was expanded because of the increasing number of transports to the camp. At its peak, the Kanada Kommando consisted of approximately 1,000 men and women.

- Tadeusz Borowski, This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen, Penguin Books, London, 1976, p. 36.

The Arrival

The ArrivalArrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau

Cecilie Klein-Pollack:

“ […] we arrived to Auschwitz. As soon as they opened the doors, prisoners in striped uniforms came on to the train and they started to, to yell that we should all leave everything and go down — we all must go out, leave everything in the train. My brother-in-law by some miracle had still a watch. So he — you know, he asked them first, “tell me what’s going on here.” And downstairs we just heard a lot of screaming and, yelling in, in German. […] My sister — as soon as they opened the door, she ran down with her little boy; because Danny was crying and, and it was suffocating in, in that train it was terrible, terrible journey. People were fainting. We, we, were pulling out you know, that — smelling salts to revive people. It was unbelievable to describe just the journey itself, so we were already very glad when we arrived, at the arrival. We thought, “This is, this is — at least can’t be worse than, than what we experienced.

Helena Cytron (after the war, Ziporah Tahori)

Helena Cytron was born in 1922 in Czechoslovakia. In spring 1942, when she was twenty years old, she was deported to Auschwitz in one of the first transports from Slovakia. While in the camp, she worked in different labor groups, among them “Komando Kanada.” Because of this work she managed to save her sister, Shoshana, from death. In 1945, she participated in the death marches, and with liberation she and her sister immigrated to Israel. She had two children, and lived in Tel-Aviv until her death in 2006.

Just as we arrived at Auschwitz, the terrible shouting started: “Alles Raus!”’ “Everyone out!” “Hurry up!” Everything happened very fast, accompanied by shouting, and by the time we gathered ourselves up, and we could once again stand on our feet (for our feet had become paralyzed from sitting), the beatings began. From the minute we got to the door, anyone who could not jump quickly was whipped, and there were SS personnel and dogs. As soon as we got off the trains, they asked us to throw [the rest of] our jewelry onto the side of the road — whatever people still had: small earrings, a watch — for they had taken away our jewelry long before.

Batya Druckmacher

Batya was born in Lodz in 1914. Before the war, she was a housewife, and in the Lodz ghetto she worked as a nanny. She arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1944, and by the end of the war, had survived Auschwitz, Bergen-Belsen, forced labor camps in Germany, and Dachau.

On October 20, 1944, all Jews of the ghetto were sent to Auschwitz. We arrived there late at night, and sat in the boxcars until six o’clock in the morning. From far away we saw how they led men, barefoot and head-shaven, to work. These men begged us to throw them a piece of bread, because we, too, would someday be as they were. Then the panic started among the people. Some began to cry and the German Kapos, who were leading the men, hit them with sticks on the soles of their feet. We threw them bread without paying any attention to the Kapos who walked along accompanied by their dogs.

Feige Sauberman

Feige was born in Klementow in 1922. From a BMW factory for car production in Munich where she performed forced labor, she was sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. She was later sent to Bergen-Belsen, and was incarcerated in three other camps before she was liberated.

On May 18, 1944, we arrived in Auschwitz. It was night. Despite the tortures and the despair each one of us was curious about our fate. The only source we had for information was the SS men accompanying us to Auschwitz. They gave evasive answers to our questions. Upon looking at the huge flame, we asked them whether it’s a factory? They answered us with a cynical laugh, explaining that this was the kitchen where they make coffee for the workers. As we got closer to these flames, we immediately had the opportunity to understand what kind of a kitchen it was.

Imre Kertesz

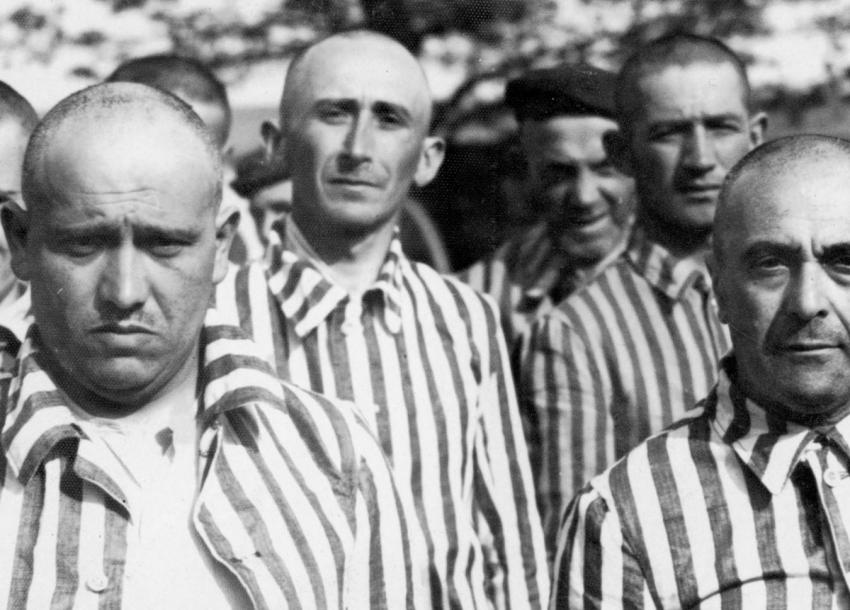

Then I was awakened by movements and excitement. Outside the sun shone in its full glory. The train was moving again. I asked the boys about our location, and they replied, “Still there. We just began moving.” So I must have been jolted awake. But without a doubt, they added, directly in front of us one could see factories and some kind of settlement. A minute later, those stationed in front of the window reported, and I also noticed by the alteration in light, that we must have slid through some sort of an arched gateway. After another minute the train stopped and than the viewers excitedly let us know that they could make out a station, soldiers, and people. Several persons immediately began gathering up their belongings and buttoning up; the women especially began cleaning up, prettying up, and combing themselves. Outside, however, I heard approaching knocks, the slamming of doors, and the jumbled noise of departing passengers, and I was now forced to realize that without a doubt we had indeed arrived at our destination. I was glad naturally, but I felt that I was glad differently from the way I would have been, let’s say, yesterday or, even more exactly, the day before yesterday. Then some tool banged against our car’s door, and someone, or rather several people, rolled aside the heavy door. First I heard their voices. They spoke German or some closely related language. It sounded as if they were all talking at once. From what I could gather, they wanted us to leave the cars. But instead, it seemed they squeezed themselves in among us; for a moment I could see nothing. But the news soon spread: suitcases and packages should stay there. Later they explained, as the words were translated and passed around, later everyone would be given back his belongings, of course. […] Then the natives approached me, and I finally caught my first glimpse of them. I was quite surprised, because, after all, this was the first time in my life that I had set eyes on — at least in such close proximity — real convicts, clad in the striped suits of criminals, with shaven heads and round caps.

- Looking at the photos, what can we learn about the people’s understanding regarding their destination?

Notes to the Teacher:

They brought luggage, toothbrushes, hairbrushes, clothes, dishes. They thought they were going to be resettled so they packed items that might prove useful, including valuables that could be used to bribe officials. - How did they describe the scenes, sounds, and smells they encountered upon arrival?

- The scenes that Helena Cytron and Batya Druckmacher describe in their testimonies are not entirely reflected in the photographs. We do not see SS officers in the photographs, nor dogs, nor complete chaos. The individuals photographed do not appear particularly ill or panicked.

Notes to the Teacher:

Consider the motivation of the photographer in taking these photos. There is often a gap between reality and its depiction. For this reason, it is important to use additional sources, especially testimonies from the victims’, in order to gain the best understanding of the situation. Students should be reminded that Nazis wanted to avoid chaos, even to the extent that they might act without violence in order maintain calm and order. - Why did the Nazi staff behave as they did? Why did they scream and conduct everything so fast?

Notes to the Teacher:

The rapid pace left no time to think but only to act according to orders. There was no time to comprehend what was going on, or try to resist. This was part of the dehumanizing process that made it easier for the perpetrators. - How and why did the Germans deceive the victims about what was happening there?

Notes to the Teacher:

The Germans tried to make the process appear as “normal” as possible. If people believed that they were being transported by train to labor camps, the order and pace of the murderous system would be preserved. It was also important to conceal the truth from the world at large. Thus, the victims were sometimes allowed to send postcards to their relatives suggesting a hopeful future. A truck with the Red Cross on it made them feel more secure, even though the truck really carried the poison gas Zyklon B. - Imre Kertesz describes the first moment of seeing “real convicts, clad in the striped suits of criminals, with shaven heads and round caps.” Are these people really criminals? What is their crime?

Notes to the Teacher:

It is important to emphasize that these people committed no crime. It is only because they were Jews that they were sentenced to forced labor and death. - For advanced groups: Research events occurring in the same month that these photos were taken. For example, what was happening to the Nazi war machine in May 1944?

Notes to the Teacher:

In May 1944, Germany was under intense pressure from the Soviet Red Army on the Eastern Front, and would soon face the decisive Allied invasion on D-Day of Normandy on the Western Front. In spite of these increasing threats, the Germans continued to use vast resources in its war against the Jewish people, even when this affected its military needs.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Interview with Cecilie Klein-Pollack, May 7, 1990, RG-50.030*0107.

- Helena Cytron, Yad Vashem Archives, O3/6766, VT 185.

- Batya Druckmacher, Yad Vashem Archives, MIE/555.

- Feige Sauberman, Yad Vashem Archives, M49E/2518.

- Imre Kertesz, Fateless, pp. 57-58.

The Selection

The SelectionThe Selection Process

Cecilie Klein-Pollack:

So my brother-in-law asked them, “What’s going on here” So he, of course, didn’t answer. So he had a watch, and he goes and he slips him the watch; and he tells him—and my sister was in the meantime downstairs, and I was always sticking next to my mother. So he said to her, “Listen, if you have, children, then give it away to, to either older people or, or the women with children, because women and children and anybody older is going to be killed. They are killing the same night, the same day. There is no chance for these people to survive. “I couldn’t even believe it. And my mother had the presence of mind to, as soon as she, heard that—she didn’t know, this was my mother—then this man said it, she ran down with me, and, and I ran after her; and she goes over to my sister, and she has the presence of mind to tell her, “Listen, Darling, I just found out that women and children will have it very easy. All they will, all they are going to do is take care—is take care of the children. But—and, and if I don’t have a child, then they will send me in hard labor. And you know I will never survive hard labor. But you are young, and you’ll be able to survive.” And before my sister has a chance, you know, to go not to give the child, my mother moved the child from her arms. And, and, and as soon as she removed—she had the child in her arms, she was pushed to this other side, you know, with all the women and children.

Livia Lieberman

They told us to leave the bundles in the boxcars. They put the elderly on one side and the younger people on the other side, men and women separately. They separated the children from their mothers, the wives from their husbands. We were forbidden to take leave of each other, so we were parted from our dear ones without a word. They hit us, they beat us mercilessly.

Batya Druckmacher

One of the bullies asked me whose child was standing next to me; my sister, who was standing close by, wanted to save me, and she said the child was hers. When I yelled out that the child was mine, I was beaten for lying. Then they took away my child, and my sister also went…

Regina Widawska

Regina was born in Lodz in 1913. Before the war, she worked as a nurse in the Jewish hospital in the city. She arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau in August 1944 from the Lodz ghetto. After the evacuation from Auschwitz she was in Freiburg and Mauthausen camps.

On the twenty-eighth of August, we were sent to Auschwitz. When they opened the boxcars, the “Canadians” appeared immediately. That is how the Jews who worked in the warehouses were called. We were ordered to leave everything in the boxcars, and to hand over our valuables. Then we understood that we were going to be killed. I immediately threw down my bundles, but my mother did not want to hand over her knapsack. They told us to line up single file. I stood next to my mother. One of the “Canadians” came up to me, and told me: “Move away from your mother, because two hours from now, she will no longer be alive.” My mother heard what he said. Before I could make sense of what was happening, an SS man pushed me towards one side, and my mother to the other side. They immediately organized the selection, and I never saw my mother again.

Eliasz Skoszylas

The Gestapo man who was running everything was so skillful that we did not manage to make sense of what was happening, and almost immediately some of the elderly and the children found themselves in cars taking them in the direction of the crematorium. I do not know what went on in those cars. I only felt that I had ceased to absorb impressions and that everything had died inside me.

Olga Elbogen

Well, with my sister, with the next to me younger sister, they put us to the right side, only the two of us, and we didn’t even say goodbye to Mother and the little ones. We just had some food yet from home and I gave it to my mother, “We’ll see you tonight.” And that was it and I never saw them again. It was such a commotion there in Auschwitz that we didn’t know.

After examining the photos and reading the attached testimonies, students should address the following questions in small groups.

- Read the following diary extract and answer the questions.

Rudolf Hoess (Commandant of Auschwitz)

During the whole period up until 1944, certain operations were carried out at irregular intervals in different countries […]. Each series of shipments lasted four to six weeks. During those four to six weeks, two to three trains, containing about two thousand persons each, arrived daily. These trains were first of all shunted to a siding in the Birkenau region and locomotives then went back. The guards who had accompanied the transport had to leave the area at once and the persons who had been brought in were taken over by the guards belonging to the camp.

They were there examined by two S.S. medical officers as to their ability to work. The detainees capable of work at once marched to Auschwitz or to the camp at Birkenau. And those incapable of work were at first taken to the provisional installations, then later to the newly constructed crematoria.

- What is a “selection”? Why did the Nazis make these selections?

Notes to the Teacher:

a. From the testimonies of the survivors we can learn of the horror, the pain and the trauma. But the question that isn’t answered from the their testimonies is, how was it humanly possible? Who was able to perform such murder? This is the importance of bringing the perpetrator’s point of view. It is stressed in the testimony the cold mechanism and description.

b. When using a primary source, a few points must be stressed, such as, who is the witness, what were the circumstances of surrounding its creation, what was its time period, etc. The testimony given by Hoess was recorded during his trial. A parallel testimony can be found in his diary, written during the months he was imprisoned in Poland, awaiting the verdict.

c. Auschwitz was a concentration camp as well as an extermination camp. Therefore, they selected the few who could work, while the rest were sent to their deaths. Those sent immediately to their deaths were deemed incapable of work, primarily the elderly, mothers and children. - What information do the testimonies add to what you notice in the photographs?

- According to the testimonies that you’ve read, how quickly were things moving during the “selection”? From the testimonies, how did it affect people?

Notes to the Teacher:

The rapid pace of events left people without time to bid farewell to loved ones, and confused about their whereabouts and their destination. This was part of the intentional camp system. - What are the dominant feelings witnesses describe during the “selection”?

- Many Holocaust survivors describe the “selection” as the most traumatic moment. Can you explain this?

Notes to the Teacher:

The separation of families, and inability to say goodbye was painful. Many survivors felt guilty that they remained alive while their families perished. It is incomprehensible to deal with a world of chaos. - What happened to Jewish families during the selections?

Notes to the Teacher:

Families were separated, but many times mothers tried to save their grown children by taking their babies from them, knowing that their child stood the only chance of survival. Not understanding this scenario, some decided to stay with their mothers, initially unaware that this sentenced them to death. - What was the fate of most victims after the selection?

Notes to the Teacher:

Answering this question can be done through the photos. Bear in mind that the majority of victims were sent to their deaths upon arrival, while the rest were sentenced to be exploited for forced labor until death. For further reading, see Handout 2. - How did prisoners try to help the new arrivals, if at all? What kinds of dilemmas did they face?

Notes to the Teacher:

Many times, prisoners tried to tell the new arrivals about their whereabouts, and what they should do to survive. The question was whether to tell them anything because, some were executed for revealing the truth. As Tadeusz Borowski said, “The camp’s law is that those going to their death should be deceived until the end.” Why?

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Interview with Cecilie Klein-Pollack, May 7, 1990, RG-50.030*0107.

- Livia Lieberman, Yad Vashem Archives, M4 9E/80.

- Batya Druckmacher, Yad Vashem Archives, MIE/555.

- Regina Widawska, Yad Vashem Archives, M49E/4123.

- Eliasz Skoszylas, Yas Vashem Archives, M49E/227.

- Olga Elbogen, Yad Vashem Archives, O3/10335.

- Rudolf Hoess (1900–1947), born in Baden-Baden, Germany, volunteered for the German army during World War I even though he was underage. In 1922, joined the Nazi Party, and in 1934, the SS. From 1934-1938, Hoess administered the concentration camp at Dachau. In May 1940, transferred to the site of Auschwitz, where he played a major role in organizing and setting up and camp, and was made commandant. In May 1941, Himmler ordered to establish a new camp near Auschwitz; this became Birkenau, or Auschwitz II. From summer 1941 to November 1943, Hoess presided over the murder of Jews from all over Europe. Responsible for the implementation of Zyklon B gas for that purpose. Left Auschwitz at the end of 1943, but returned to head the extermination of Hungarian Jewry. In all, responsible for the deaths of more than a million people. After the war, escaped and assumed a false identity, but was discovered and arrested in March 1946. The Supreme Court in Warsaw sentenced him to death; hanged in Auschwitz on April 16, 1947.

- From the Testimony of Rudolf Hoess The Trial of German Major War Criminals, Part 11, 4 April 1946–15 April 1946.

The Absorption

The Absorption

Photo 22: Jewish female prisoners who have been selected for forced labor are marched to a different section of the camp

Jewish female inmates marching in the women’s camp in prison clothes. Birkenau. May 27, 1944 (Photo 25)

Photo 28: The barracks in the “Kanada” section were insufficient and a large amount of stolen personal items filled the space between the barracks

Photo 29: Personal items that were stolen from the prisoners when they entered the camp. They will be sorted at “Kanada.”

Absorption Process: Dehumanization and Transformation into a Prisoner (Häftling)

Cecilie Klein-Pollack

This is where my mother and all the others were, in that gas chamber. And we were in another place that we had to undress and dress and they took everything away from us. And they shoved us into the showers, that we have to—but what they did is, they first opened the hot water so we got scalded and then they opened the cold water; so as we, were running out we, were all so—and first they shaved us. […] we were completely, you know, they shaved our hair and they shaved our, our private parts; […] and then they gave us—each one got some rag to put on. […] as if somebody could get a size six that needed a, a size 15, and somebody got a, a six—and vice versa. And so that when we, were lined up, we didn’t even recognize each other.”

Helena Cytron (Ziporah Tahori)

So they immediately led us to a place, to some building, on which was written “Sauna,” in other words, bathhouse. We stood in line for hours, still in our own clothes with long hair, with everything, and in truth, we huddled close to each other, because they were from all over Slovakia, not just us, so we stayed close to our friends from home, we felt safer when we were together. And thus, after we had stood for hours, we saw that behind this house, behind the wall, there were some strange figures wandering around, and we decided that there must be an insane asylum there. That they had opened some door there, and all kinds of crazy people had gotten out.

When we emerged from the other side, we understood that in reality those crazy people were us, and from every point of view, we had suddenly become animals, since we no longer could identify each other, and in that moment, we lost our spark of humanity, and we lost our friends. Even my best friend stood next to me, and I could not recognize her. Afterwards, after the bath, and after they had washed us—they inscribed us with numbers.

They took all our valuables from us. We were curious about what sort of work clothes they would give us. Finally, a Jewish woman came with a pile of rags that were meant to replace the dresses they had confiscated from us. I was given a worn out black skirt and a worn out crepe blouse. No one was given undergarments. The shoes were not intended for both feet. One woman could not even put on the shoes she had been given because they were too narrow. A German came over to her and asked why she was not wearing her shoes. When he heard her answer, he kicked her a few times, and she was not able to get up.”

Primo Levi

Häftling: "I have learnt that I am a Häftling. My number is 174517; we have been baptized, we will carry a tattoo on our left arm until we die.”

We Italians had decided to meet every Sunday evening in the corner of the Lager, but we stopped it at once, because it was too sad to count our numbers and find fewer each time, and to see each other ever more deformed and more squalid. And it was so tiring to walk those few steps and then, meeting each other, to remember and to think. It was better not to think.”

After examining the pictures and reading the testimonies, students should answer the following questions:

- What physically happened to the prisoners in the hours after they arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau?

Notes to the Teacher:

It is important to emphasize the rapid pace of stripping the newcomers from their identity and turning them uniformly into prisoners, a dehumanizing process. - What was the significance of this change from the Nazi perspective? How did the dehumanization serve the perpetrators?

- How do survivors describe the treatment of the Nazis and their collaborators in the camp?

Notes to the Teacher:

All testimonies emphasize the violence and abuse. Women stress the violation of the body. - What happened to the prisoners psychologically soon after they arrived at the camp?

Notes to the Teacher:

MThey describe a sense of no longer feeling human. Depression set in quickly, as people realized the amount of deaths in the camp, and feared that they would join the victims.

Show students photographs 27-32, and read the following testimony from the camp commander.

Rudolf Hoess

By 1942, Canada I could no longer keep up with the sorting. Although new huts and sheds were constantly being added and prisoners were sorting day and night, and although the number of persons employed was constantly stepped up and several trucks (often as many as twenty) were loaded daily with the items stored out, the piles of unstored luggage went on mounting up. So in 1942, the construction of Canada II warehouse was begun at the west end of building sector II at Birkenau. […]

When the storing-out process that followed each major operation had been completed, the valuables and money were packed into trunks and taken by lorry to the Economic Administration Head office in Berlin and thence to the Reichsbank, where a special department dealt exclusively with items taken during actions against the Jews.”

Notes to the Teacher:

At the beginning of the lesson we considered the belongings of the transported people in order to understand something of the state of mind of those who arrived at Auschwitz. Hoess’s testimony gives us the Nazi perspective. What did the Nazis do with all these belongings? They sorted and shipped them to Germany to be reused. As part of the system, the Nazis exploited anything possible—including hair, dental fillings, and even the ashes of the victims.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Interview with Cecilie Klein-Pollack, May 7, 1990, RG-50.030*0107.

- Helena Cytron, Yad Vashem Archives, O3/6766, VT185.

- Primo Levi, If This Is A Man? (New York: Orion Press, 1958), pp. 22, 34.

- Rudolf Hoess, Commandant of Auschwitz — The Authentic Confessions of a Mass Murderer; With an introduction by Lord Russell of Liverpool (London: Pan Books, 1961), pp. 219, 220.

The Murder

The MurderOn Their Way to Death in the Gas Chambers

Feiser Silberman

We saw a long window stretching the length of the monstrous structure that was hermetically closed with wide iron bars. Along the length of the window stood naked figures from groups that had earlier been taken off [the boxcars] with beatings and dogs.... These misfortunate people were apparently aware of the fate awaiting them. With shouts of despair and heart-wrenching cries they called to God and their relatives.... After we saw what happened here, we no longer doubted that the Auschwitz camp was Hell.

Haya Pomeranz

Haya was born in Kresnik in 1910. She arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau from Majdanek. From there she was sent to Bad-Achen, and Bergen-Belsen.

They took the children from their mothers, everyone was screaming, but the heavens did not open and God did not help them. The clouds wept small drops, but no one paid attention to the cries of the children. They led them to the gas chambers and from there to the crematorium. The flames licked the sky, but nothing happened, because God and the angels were asleep.

What is common to all those who appear in the photographs? According to Nazi ideology, all Jews were condemned to death. However in Auschwitz—a labor camp as well as a death camp—some of the Jews were first taken to forced labor. The people in these photos are all considered to be unable to work—elderly people, mothers with infants, and young children. Moreover, women were the ones who would give birth to the next generation, and along with children, represented the future.

- The deaths of the majority of Jews were not documented. There were no monuments or graves to visit as would normally be the case when a family member dies and is buried according to Jewish traditions. Thus we see the importance of the work of community memorial societies and Yad Vashem in gathering the names and documenting those who died and those who survived. For more information, check Yad Vashem’s website and the database of names.

Years after the Holocaust, the Israeli poet Meir Wieseltier wrote in his poem, Milim — Words:

Words

Two years before the destruction

They did not call ‘destruction’ ‘destruction’

Two years before the Holocaust

It did not have a name.

What was the word ‘destruction’

Two years before the destruction?

A word for something bad, that should never happen.

What was the word ‘Holocaust’

Two years before the Holocaust?

It was a word for a great upheaval

Something with a tremendous din.

Meir Wieseltier is an Israeli poet and translator. Born in Moscow in 1941, he came to Israel in 1949. He studied law, philosophy, and general history, and was awarded the Bialik Prize in 1995, and the Israel Prize for poetry and literature in 2000.

How do you interpret this poem?

- Feiser Silberman, Yad Vashem Archives M49E/2948.

- Haya Pomeranz, Yad Vashem Archives, MIE/1385, MIE/1339.

- Meir Wieseltier, “Words.” Translated by Gabriel Levin; Tel-Aviv Review, edited by Gabriel Moked, 4 (Fall 1989–Winter 1990): 191.

Lili Jacob

Lili JacobLili Jacob and the Auschwitz Album

In April 1945, Lili Jacob was liberated from the Dora-Mitelbau concentration camp by the American army. When she heard that the camp was liberated, she came out to greet the soldiers, but collapsed from weariness. Other inmates carried her to one of the deserted German barracks. When she regained consciousness, she was cold, and searched in a cabinet next to her bed for something warm to put on. There she discovered a photo album, and as she looked through it, she saw photos of people from her hometown Bilke, including her own brothers and grandparents (Photographs 41 and 42). Lili kept the album.

She returned to her hometown in July 1945, hoping to find her relatives. But of her whole extended family—parents, brothers and sisters, grandparents, aunts and uncles—only she survived. Friends and acquaintances learned about the existence of the album and came to look through it, to see their loved ones who had perished. Some asked to keep the photos of their families, and Lili agreed; this explains why some of the original photos are missing today.

Lili presented the album to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority, at a formal ceremony in Jerusalem on August 26, 1980. In her speech, she said that she felt great relief, believing that the album really belongs to the Jewish people. “A heavy weight has been removed from my heart knowing that the album will appear in a permanent exhibit at Yad Vashem.” At the end of the moving ceremony, Lili was awarded the Yad Vashem medal. Two days later, she was invited to meet with the then Israeli Prime Minister, Menachem Begin, who expressed a desire to see the album. On her way back to the United States, Lili went to Poland for the first time since the war and visited the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum.

The photographs Lili Jacob saw when she found the album in May 1945: