No monument stands over Babi Yar.

A droop sheer as a crude gravestone.

I am afraid.

Today I am as old in years

as all the Jewish people.

Now I seem to be

a Jew.

Here I plod through ancient Egypt.

Here I perish crucified, on the cross,

and to this day I bear the scars of nails.

I seem to be

Dreyfus.

The Philistine

is both informer and judge.

I am behind bars.

Beset on every side.

Hounded,

spat on,

slandered.

Squealing, dainty ladies in flounced Brussels lace

stick their parasols into my face...1

An estimated 70,000 to 100,000 people were murdered at Babi Yar during the German occupation of Kiev. In addition to Jews, who were the majority of the victims, the area served as the execution site of mentally and physically disabled persons, Soviet prisoners of war, partisans, members of the underground, communists, gypsies, Ukrainian nationalists and anti-Nazi activists. The frontline correspondent of the Pravda newspaper Boris Polevoy was one of the first people to visit Babi Yar after the liberation of Kiev in November 1943. He later shared his impressions of the horrors he had witnessed:

"We entered Kiev with the first Soviet troops. The city was still burning. But we, all the correspondents, were eager to visit Babi Yar. We had heard a lot about it over the years, but we had to see everything for ourselves… We came to Babi Yar and stood transfixed. Huge deep pits. The day before, the city had been bombed, and one of the bombs struck the slope of the ravine. The explosion severed a piece of the slope at the bottom. And we saw the unimaginable: a compressed monolith of human remains between layers of soil – like a geological deposit of death. Even in my worst nightmares I could not have imagined something like that… I could not believe this was possible. I did not see anything more horrible during the entire war.”2

The famous poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko Babi Yar, quoted above, was written in 1961, 16 years after the end of the war and 18 years after the liberation of Kiev. It starts with the words "No monument stands over Babi Yar", which describes the reality of the postwar official policy regarding commemoration of the victims of the war and the Holocaust – in Kiev in particular, and in the Soviet Union on the whole.

Babi Yar became both the symbol of extermination of Soviet Jews, and the symbol of the official Soviet campaign to suppress any public discussion of the Holocaust. However, at the same time, it must be stressed that the story of Babi Yar cannot serve as a general example of Holocaust memorialization in the Soviet Union. This is an important point, and we will return to it later on in the lesson.

For many decades it was commonly believed that commemoration efforts of the victims of the Holocaust in the USSR only began after the fall of the "Iron Curtain". Following the opening of previously sealed Soviet archives, the latest studies on Soviet Jewry have shown this belief to be false and unfounded. These studies proved that commemoration attempts had in fact begun at a much earlier stage – the days immediately following liberation. In the majority of cases, the initiators of these attempts were demobilized Jewish soldiers and survivors who had lost their families during the occupation. After returning home, these Soviet Jews thought it extremely important to commemorate the memory of their loved ones who had perished. The immense tragedy and pain, the memory of the murdered, the desire to preserve their names and to erect memorials at the sites of their executions, were shared the majority of the Soviet Jews.

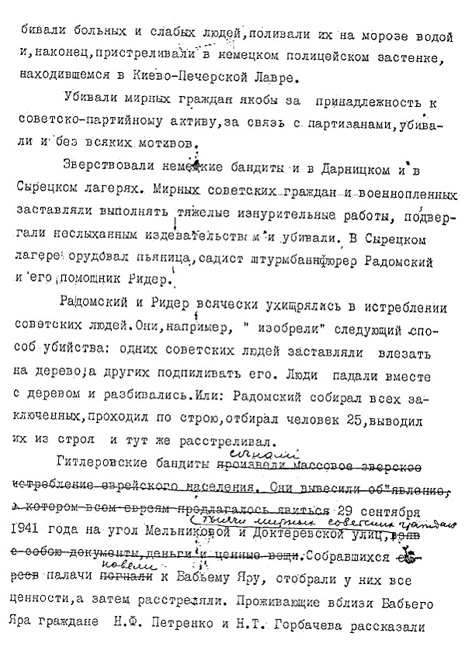

In Kiev, the attempts of the Jews who had returned from the front to commemorate the victims of Babi Yar began shortly after the liberation of the city on November 6, 1943. These attempts were met with opposition by the Soviet authorities, who adhered to the idea of a collective memory and did not want to divide the victims into separate categories. This trend dominated Soviet memorialization policy up until the Perestroika. It was molded as early as the beginning of 1944, when the reports of the State Extraordinary Commission for the Determination and Investigation of Nazi and their Collaborators' Atrocities in the USSR (ChGK) were published. In many cases, these reports deliberately ignored the victims' Jewish origin (this same trend can be observed in the inscriptions found on monuments erected at the sites of mass murders of the Jewish population throughout the former USSR. These monuments deliberately avoid mentioning the victims' ethnic and religious origin). Thus, in the ChGK report about the killing of the Jews in Babi Yar, published in February 1944, all mentions about the ethnic background of the victims were removed, and the word “Jews”, which was present in the December 1943 variant of the report, was replaced by the universal term “Soviet civilians”.

Yet during this time of silencing, opposing voices were being heard on the cultural and intellectual front. One such example is Ilya Ehrenburg’s poem Babi Yar, which was published in 1944. Referring to the horrors of the events and to the scar they had left in the collective and individual memory, this poem would become one of the elements shaping the place of Babi Yar in collective memory.

On March 13, 1945, the Council of People’s Commissars of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic decreed that a monument should be erected in Babi Yar. The plan was not destined to be carried into effect – it was suspended as a result of the Antisemitic campaign against “cosmopolitans”, which had begun in 1948-1949. After Stalin’s death in 1953, the subject of the Holocaust of the Soviet Jews continued to be repressed and the question of erecting a monument in Babi Yar remained unaddressed and for an extended period of time.

In the mid-1950s, Babi Yar was partially covered with soil, and two motorways were built through it. One of these divided the territory into northern and southern parts. In the southern part, a mini-park was created; later, garages were built on some of its territory. The grounds of the northern part were used to build a residential estate, a sports center and a park.

On March 13, 1961, the “Kurenivka mudslide" tragedy struck. Loam pulp that was pumped through pipelines to Babi Yar, broke through the protective dam and flooded the city district of Kurenivka. Hundreds of people died and a residential estate and a tramway depot were destroyed. Writer Anatoly Kuznetsov recalled that this tragedy gave rise to popular superstitions – many residents of the city believed that Babi Yar “was taking revenge” on those who had attempted to erase all memory of it.

Nevertheless, even during these years and despite the authorities' silencing policy, the subject of Babi Yar continued to resonate throughout the Soviet society. This was mainly thanks to the activities of cultural figures and members of the intelligentsia – both Jewish and non-Jewish. In 1959, responding to the official plan to build a stadium on the grounds of Babi Yar, writer Viktor Nekrasov wrote the following in the popular Literaturnaya gazeta newspaper:

"...I’ve just been told by the architectural administration of the city of Kiev that Babi Yar is intended to be “flooded”… in other words, filled with soil, levelled, and in its place a garden and a stadium will be built…

Is this possible? Who could have taken it into his head – to fill a ravine 30 meters deep and play football and run about at the site of the greatest tragedy?

No, this cannot be allowed to happen!” 3

In September 1961, in the same newspaper, the poem Babi Yar by Yevgeny Yevtushenko was published. It was written after Yevtushenko's visit to Babi Yar, where the poet was shocked by the fact that the burial site of tens of thousands of innocent victims was turned into a dump. The poem's publication caused an extreme public reaction, both in and outside the USSR. Yevtushenko was praised by many who recognized the injustice of the Soviet campaign to silence the history of Babi Yar. At the same time official Soviet discourse attacked Yevtushenko for his "insolence". He was accused of particularism, political immaturity, and historical ignorance. This however did not deter those who supported him. Composer Dmitriy Shostakovich expressed his support by putting Yevtushenko’s poem to music in his Symphony No. 13. In 1966, Yunost magazine had decided to publish Anatoly Kuznetsov’s documentary novel Babi Yar (the publication was censored, and the novel was published by the author in its full form only in 1970, after he defected to London).

From the mid-1960s, the Jews of Kiev and some representatives of the Soviet intelligentsia who shared their feelings, met annually in Babi Yar, in order to conduct unofficial memorial ceremonies. This of course was done under the threat of disapproval and persecution by the authorities. Emanuel Diamant, a Jewish scientist who resided in Kiev, recalled the memorial ceremony that took place at Babi Yar on September 29, 1966:

- 3. Viktor Nekrasov, "Why wasn’t it done? (About the monument to the perished in Babi Yar in Kiev)", "Literaturnaya gazeta", October 10, 1959.

"We announced to everyone with whom we were able to communicate that at the appointed hour we would be at the entrance to the old [i.e, former] Jewish cemetery and asked everyone to join us. And people came. By 5 p.m., as was set, about 50-60 people had gathered at the entrance to the cemetery… Our poster surprised everyone… On it was written (in large letters) in Russian and in Yiddish: "Babi Yar," below that in smaller script – "September 1941-1966," and above, in quite small letters – Yizkor (Hebrew for "Remember"…) the Six Million." People saw this for the first time...

But nothing else is happening. Time is passing but we don't know what to do further. We hadn't planned things out. But just to improvise on the spot was neither smart nor appropriate.

Then suddenly two cars drive up. People emerge with camera equipment and immediately move towards us with cameras! It became clear to all of us – that the [K]GB had arrived in order to film and record us!...

Faced with the cameras, people began to take off quickly. Very soon, there remained about 15 of us, no more. We stood there, huddled together like orphans…

And then some unfamiliar person suddenly is joining our group and, extending his hand to me, said: "I am [Viktor] Nekrasov…

Viktor Platonovich [Nekrasov] was very bothered by the sad experience of our silent standing there... "You have to come up with something. The actions need to have some focus."

Finally, he suggested: "We need to erect a monument. At least some kind of one. Whether a temporary one, one of wood or plywood, some kind of monument." 4

- 4. From the memoirs Babi Yar or Memory about How an Obstinate Tribe Became a People by Emmanuel (Amik) Diamant, September 14, 2011.

who had been murdered in Babi Yar, Viktor Nekrasov said: “That’s true, all kinds of people were killed in Babi Yar, but only Jews were murdered just because they were Jews… And don’t forget, this was the first case of mass extermination of the Jews. Auschwitz was later…”

The daring initiatives these activists took, the publications of Nekrasov and Yevtushenko in the USSR during the so-called “Thaw”, and the attention of the western press, attracted public attention to the on-goings in Kiev. This in turn forced the Soviet authorities to readdress the issue of erecting a monument in Babi Yar.

In 1976, under pressure from international organizations, a monument to the memory of "Soviet civilians and Red Army soldiers and officers - prisoners of war - who were shot at Babi Yar by the German occupiers" was erected. The monument was built in the Soviet monumental style and did not contain any mention of the victims' exact identity. In travel guides and reference books, the memorial was referred to as “the monument in the Syrets district”.

After the fall of the “Iron Curtain”, on September 29, 1991, a Menorah shaped monument was erected in Babi Yar, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the first mass shooting of the Jews of Kiev, (it was created by the sculptors Akim and Alexandr Levich, the architect Y. Paskevich, and the designer B. Giller). Leading to the Menorah is “The Road of Woe”, a path paved with tiles, located between the site of the former offices of the Jewish cemetery and the monument itself.

In later years, in independent Ukraine, other monuments were erected in Babi Yar. These commemorate both Jewish and non-Jewish victims. Among them is the monument to the murdered children, unveiled on September 30, 2001. It is located opposite the “Dorohozhychi” subway station, at the site where the Jews of Kiev were led to their place of execution in September 1941. The monument shows three figures of children, the dedication says: "To the children shot in Babi Yar. 1941".

We will mention some other Babi Yar monuments. In February 1992, a cross was erected in memory of the 621 members of the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) executed there. Another cross, in memory of the archimandrite Aleksandr Vishnyakov and the archpriest Pavel who urged people to resist the Germans and were consequently killed on November 6, 1941, was installed in 2000. In 2005, a stele was installed in memory of Ostarbeiters and concentration camp prisoners. In March 2006, a bell-shaped monument to the victims of the Kurenivka mudslide was unveiled. Another monument is dedicated to the patients and staff of the Pavlov psychiatric hospital who were shot here on September 27, 1941, thus becoming the first victims of mass murders at Babi Yar. A discussion is currently being held regarding the building a monument commemorating the Roma (gypsies) murdered at Babi Yar.

Since 1991, mourning rallies are held annually at Babi Yar on September 29. Ukrainian public officials, the Israeli ambassador to Ukraine, representatives of international Jewish organizations, delegations from various countries, and the Jews of Kiev all take part in these. On March 1, 2007, by the decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, the State Historical and Memorial Park of Babi Yar was created.

Over the years Babi Yar has become an international symbol of the Holocaust and of the plight of Soviet Jewry. At the same time, the history of this place, the diverse character of its victims – both ethnically, and in other aspects– the postwar struggle for commemoration, the number and variety of the monuments erected, the wide-spread representation of its history in art, literature, music and cinema – all give Babi Yar universal meaning, and make it the ultimate symbol of human tragedy. It forces humanity to confront global questions about basic human values, the nature of hatred, the risk of moral degradation, the value of human life, and the existence and necessity of learning the lessons of history.