The bericha [Hebrew] refers to the organized attempts, during 1944-1948, to collect Jewish survivors in Europe and bring them to pre-state Israel. This site features an animated exhibition, interactive map and educational discussion material on the subject.

Under the Ruins of Poland / Itzik Manger

Under the ruins of Poland

a golden head lies

both the head and the destruction

are very true.

The snow continues falling

over the ruins of Poland

the golden head of my beloved

in front of my aching eyes.

Pain is sitting at the desk

and writes the longest letter.

The deep tears in her eyes

are very true.

A large bird of mourning

flies above the ruins

carries in her wings

the song of grief

over the ruins of Poland.

Towards the end of the Second World War, in 1944-45, Soviet, British and American soldiers liberated the remnants of European Jewry from the Nazi extermination, concentration and labor camps. During the first weeks after liberation, the survivors suffered from various diseases, severe malnutrition and a depressed emotional state. After a period of time, many of them tried to return to their prewar homes and search for family members. In many cases, the hope of discovering someone alive was fast extinguished and the majority of Holocaust survivors, now displaced persons, found themselves without family, homes and communities. As a result, many believed that they had to leave Europe which had, to them, become “a vast cemetery of the Jewish people”. Up to 250,000 of the survivors

Holocaust survivors encountered antagonism in Eastern Europe after the war. Antisemitic incidents, such as the Kielce pogrom (massacre of Jews) on July 4, 1946, undermined any hope of continued Jewish existence in Eastern Europe. In addition, disappointment with the behavior of the local population during the war contributed to their pessimistic views of the future.

In the beginning, local organizations appeared in Vilna and Rovno and helped the first survivors to steal across the borders in a rather haphazard fashion. Time had to pass before a more organized system of Bericha (“escape”) evolved.

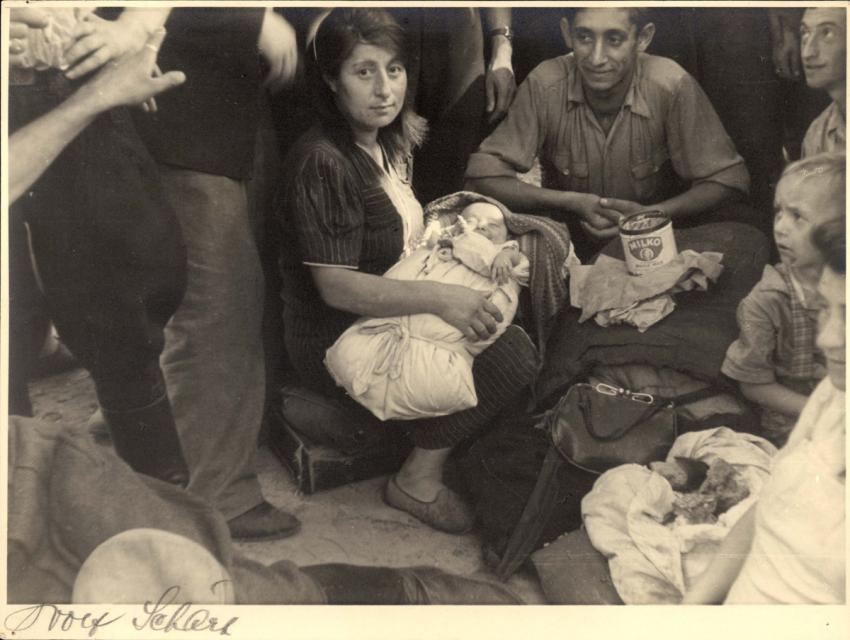

The survivors who were smuggled out by the Bericha Movement were often young, but there were also families with children who struggled to reach Palestine and start a new life. The activists working for the Bericha did not receive a salary. Necessary expenses were partially covered by the Joint (an American Jewish philanthropic organization) including transfer, food and basic living costs.

In mid-1944, the areas of Eastern Europe, Lithuania and Poland were gradually liberated. In July of that year, Lublin was liberated. Local partisan leaders and members of Zionist youth movements began organizing groups with the aim of immigrating to Palestine. These organizations encountered many difficulties, and were sometimes clandestine due to strict Soviet policies.

Many of the refugees had belonged to Zionist youth movements prior to the war, and their Zionist beliefs had been bolstered following their disillusionment with the Soviet regime; in their eyes, the natural option became Palestine. Some Jews had heard that the easiest route to reach her shores was through Romania, and thus each group attempted to reach Romania, independently of each other. Their efforts failed, and so these Zionist groups found themselves in Lublin, which had been liberated by the Red Army in July 1944. Abba Kovner headed the first organized framework of the “Bericha”, assisting 2,000 Jewish refugees to reach Romania in May 1945. When it became clear that immigration from there to pre-state Israel was not possible, they migrated to Italy, where units of the Jewish Fighting Brigade (known as the “Jewish Brigade”) were stationed. Brigade soldiers sought to bring Holocaust survivors together and send them to Palestine. The limitations and quotas placed on immigration to Palestine forced these refugees to move to DP camps in US-controlled territories within Germany. During September-October 1945, the first emissaries from Palestine, operating on behalf of the “Hagana” (Jewish pre-state paramilitary organization), arrived in Europe and began their involvement in “illegal” immigration to Palestine. Ephraim Dekel became the head of the Bericha movement throughout Europe.

Between August 1945 and the end of 1946, 41,106 Jewish refugees left Polish territory with the assistance of the Bericha, joined by many other thousands of refugees who had arrived without organized assistance (between 60,000-65,000 Jews). Following the Kielce pogrom, approximately 95,000 additional Jews fled Poland.

The stated aim of these organizations had been to reach beaches from where the survivors could set sail for pre-state Israel. After the establishment of the State of Israel, this immigration became legal, and thus the collection points of the Bericha were dismantled. However, in those countries which did not yet legally permit emigration, the Bericha movement continued to organizationally exist under Meir Sapir.

The Bericha organization represents a unique organization, and an important chapter in many Holocaust survivors’ attempts to return to a normal life, arrive in Palestine, and build the State of Israel.

- From: Leftwich Joseph (editor and translator), An Anthology of Modern Yiddish Literature, Mouton, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York, 1974, p. 282. Itzik Manger (1901-1969), prominent Yiddish writer and poet. Born in Cernauti, Bocovine, Ukraine. Published his first book of poetry in 1929. In 1939, he fled the Nazis to London and then New York. Manger published many works characterized by a rich and variegated dialog with Jewish culture. Several of his works were dramatized. Manger immigrated to Israel in 1966 and died in 1969.

- Of these, historians Yochanan Cohen estimates some 150,000 moved through organized Bericha routes, and Engel David puts the figures at around 120,000.

The roots of the Bericha movement go back to the wartime period. Zionist youth groups – Hashomer Hatzair, Hehalutz, Dror, Gordonia, Beitar, Bnei Akiva, Hano’ar Hatziyoni, Maccabi Ha’tzair and others – were involved in aiding Jews escape from German-occupied territories to Palestine. Many youth group members who had survived the Holocaust, some of whom had been involved in armed resistance inside the ghettos and in the ranks of various partisan units focused their efforts after the war, on safely transporting Jews to Europe’s borders. The stated aim was bringing Jews to Palestine, out of a sense of Zionism. Some also saw immigration to Palestine as a first step towards the survivors’ recuperation and return to normal life. The Zionist youth movements suffered heavy losses during the Holocaust, and it is against this background that their activity carries vital importance in the survivors return to life.

The following testimony focuses on the motivation behind attempts to organize the Bericha in the Vilna area.

Abba Kovner, one of the organizers and leaders of the “Hashomer Hatzair” youth group in Vilna, stated:

“If we had been thinking only about our own escape, we would not have had to do so much patrolling and scout work [to find escape routes – trans.], but foremost in our minds was how we could serve as an example and present the routes to the others [..] in order to motivate the surviving remnant to leave the land of ruin and set forth to Eretz Israel.”

Source: David Engel, Between Liberation and Flight: Holocaust Survivors in Poland and the Struggle for Leadership, 1944-1946 [Hebrew], Tel Aviv: Am Oved Publishers 1996, p. 66.

- Discuss the motivation of youth group members in organizing and carrying out the Bericha.

After the war, youth groups saw the transportation of Jews from Eastern Europe to Palestine as a top priority. Abba Kovner adds:

“I was determined that the exit from Poland was to begin immediately and without delay. The anger and pain that had accumulated in the hearts of the remnants [..] demands an outlet. Jews were longing for a fundamental change and Israel was stirring strong emotions within them, regardless of their previous Zionist background. This potential could not be wasted. Also, the political and military interim period, when permanent borders and governments had not yet been established, lent opportunity to this sort of action – we wouldn’t depend on official documents or wait until the situation had “settled”. The spontaneous action in crossing borders would only hasten political solutions. [..] [Therefore,] it was necessary to create a framework and an organization, but these would exist solely for the purposes of escaping [Europe] and reaching Palestine. Everything we would set up would be temporary and conditional on circumstance; organize only in order to gather as many Jews as possible, so they could board trucks and leave. That was my opinion”.

Source: Ibid., p. 75.

- What is the “potential” Abba Kovner mentions?

- Abba Kovner had survived the Vilna Ghetto and later fought as a partisan. How do you think his personal experiences may have influenced his decision not to wait?

During World War II, 30,000 Jews in Palestine volunteered for the British army. As part of this effort, a “Jewish Brigade” was established in September, 1944, as a separate unit within the British army. This unit was officially called the Jewish Infantry Brigade Group and numbered approximately 5,000 soldiers.

From March 1945, the Brigade fought in Italy. Two months after the Allied victory, in July, the Brigade was stationed in Belgium and The Netherlands. About 150 soldiers were secretly sent to help with the organizational and educational aspects of the Displaced Persons’ Camps, to organize the escape points in Austria and Germany and to help with the preparations for the illegal immigration to Palestine – Aliyah Bet. The Bericha activists were all volunteers and did not receive a salary. Necessary expenses were partially covered by the Joint organization as expenses incurred for transfer, food and basic living costs. The work of these people and the emissaries from Palestine was carried out in difficult circumstances and often in the face of danger. The organizational and direct help offered to the survivors enabled them to steal across borders as families and individuals and to reach Displaced Persons Camps in Germany, Austria and Italy.

Read the following survivors’ testimonies describing their meeting with soldiers of the Jewish Brigade and the related questions:

Levy Goldberg relates about his meeting with a Jewish Brigade soldier after his liberation:

“When I was liberated in 1945, I was 35 years old and I weighed 30 kilos, all skin and bones. The Americans put me in a hospital in Linz (Austria) where I remained for about a month until I returned. The first thing I saw when I got out of the hospital was a car with a Magen-David, a Star of David and I knew that they must be Jews. I reached the car and asked him who he was. He told me that he was from the Jewish Brigade and then he asked me: “Who are you?” I answered that I was one of them. We embraced each other and both cried. It’s hard for me to talk about these things but through our tears he told me that the Brigade was trying to help surviving Jews to reach Palestine.

Source: Yad Vashem archive 03/10122. (Hebrew)

- What do you think were the motives of the emissaries and the soldiers of the Jewish Brigade to reach the survivors in Europe?

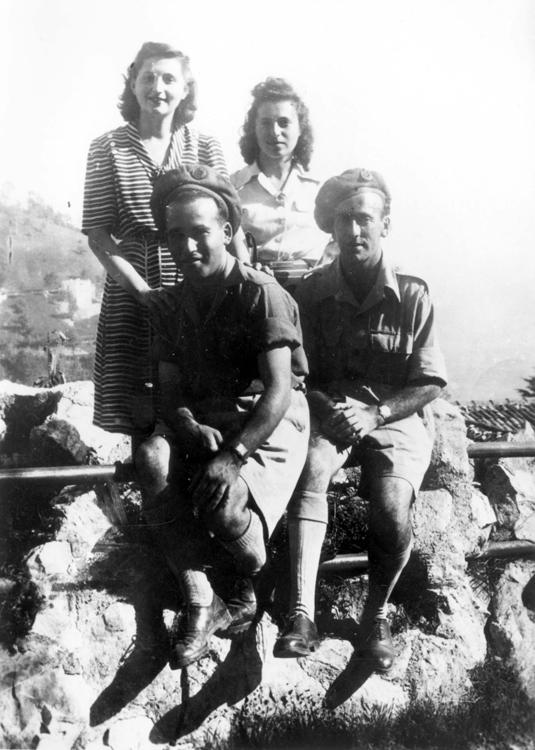

In this photograph, we see the Brigade activist, Meir Levine. Pay attention to the way in which he holds the woman’s hands, his future wife. Notice also the background in the picture and the interaction between the two.

The Decision To Immigrate To Palestine

The strong desire of the survivors to build new lives overcame the obstacles involved in emigrating from Europe. Rachel Ben-Chaim

“We crossed the borders using several stratagems, at least four or five borders. Twice we were given forged papers. We crossed the Austrian border and stayed in Graz for a day or two. We crossed one border on foot. I was carrying someone’s child. We crossed another border in a goods train. They put us in one or two wagons and closed us in. The empty goods train crossed the border to bring in goods, and we were in the wagons...

“... As far as I know, only soldiers from the Jewish Brigade did the work with us. There was a distant cousin of my husband’s there, and he came to people and said to them: ‘Come to Palestine!’. Some people broke down and turned back, because the journey was hard. The Brigade soldiers used British Army vehicles and gave us some of their rations. We had a camp hidden among the mountains. The Brigade soldiers ran it. There were also some refugees who helped to run it and other people worked there.

“Later we reached Villa Emma in Italy, and we were there for a long time without doing much. We left there later, and this is how it was: they loaded us onto lorries and tied down the tarpaulins over us. The Brigade soldiers, who belonged to the British Army, closed off the road, saying that only the army could go through, and we were the ‘army’. They took us to the harbor... they almost threw us [onto the ship], because it was all very urgent. We had to get into the ship’s hold very quickly, more than nine hundred of us. They just poured us into the ship...

“...When the ship anchored off the coast of Palestine the English discovered us. Warships surrounded us and then something happened that I shall never forget, even though 47 years have gone by since then. We dropped anchor in the middle of the sea, we hoisted the national flag to the top of the mast, and we felt that the entire Jewish people was standing on the Haifa shore, because the deck was full... you don’t forget something like that, it gave us the strength to endure many difficulties”.

Source: Yad Vashem Archive 03/6921, pp. 40-43 (Hebrew).

- What do you think motivated Rachel to endure this journey?

Shlomo Cohen was born in Greece in 1920. During the war, he was transported to Auschwitz and the British army eventually liberated him from Bergen- Belsen. He immigrated to Palestine in 1946. Shlomo relates:

“I was in that camp for about six months, but we were free, we could go wherever we wanted. Then they told us we could register either to return to Greece or go to Eretz Israel or to the United States. I registered for two places, Greece or Palestine, but what I really wanted was to go back to Greece and wait a few months to see if anyone from my family was still alive…”

Source: Y. Kleiman and N. Springer-Aharoni (Eds.), The Anguish of Liberation - Testimonies from 1945, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1995, pp. 54-55.

- What was the dilemma that Shlomo Cohen faced?

When Shlomo finally reached his birthplace of Salonica, Greece, his experiences after liberation influenced his decision to come to Israel:

“I was in Greece for about six months. From Athens I was transferred to Salonica, my birthplace, but I didn’t want to be there for even one day. Our houses were destroyed, we saw only pits instead of houses, because after we were deported the [locals] started to search for gold, they razed the houses and dug pits to look for gold. I met one Greek whom I had known before the war, and he asked me: ”Why did the Germans leave you alive?” Why didn’t they turn you into soap?” After hearing that, I understood that there was no longer place for me here…”

Source: Y. Kleiman and N. Springer-Aharoni (Eds.), The Anguish of Liberation - Testimonies from 1945, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1995, p. 54-55.

Shalom (Kaplan) Eilati was born in 1933 in Kovno, Lithuania. During the war, he was in the Kovno Ghetto, from where he was taken into hiding. He emigrated to Palestine in 1946. Eilati relates:

“In spite of it all, why Palestine? […] in my vicinity, the question never arose – it was clear that we were all on our way to Palestine. The clicking sounds of the wheels were clear and had one meaning for us – there is no-one to wait for anymore and there is nowhere for us to return to.”

Source: Shalom Eilati, Crossing the River, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1999, p. 297.

- The journey to Palestine was especially difficult and dangerous for the survivors. In light of the testimonies you have read, why do you think survivors nevertheless chose to go to Palestine?

Shlomo said: “I registered for two destinations; Greece and Palestine.” And later said: “It was clear that we were headed for Palestine.” Both survivors stated clearly that there was nothing left for them in their home countries and that they were bound for Palestine.

- These survivors made a decision to leave their previous world, which lay in ruins, for a new life. What were the difficulties in making these decisions? Do you think there was a choice in the matter?

- Rachel Ben-Chaim was born in Szaranc, Hungary in 1926. In the spring of 1944 she was deported to the ghetto in Satoraljaujhely, and from there to Auschwitz. She was imprisoned in the Stutthof camp, survived a death march in January 1945 and was liberated by the Russians. After returning home in March 1945, she left Hungary and reached Italy by August with the help of the Bericha movement. She immigrated to Palestine in January 1946.

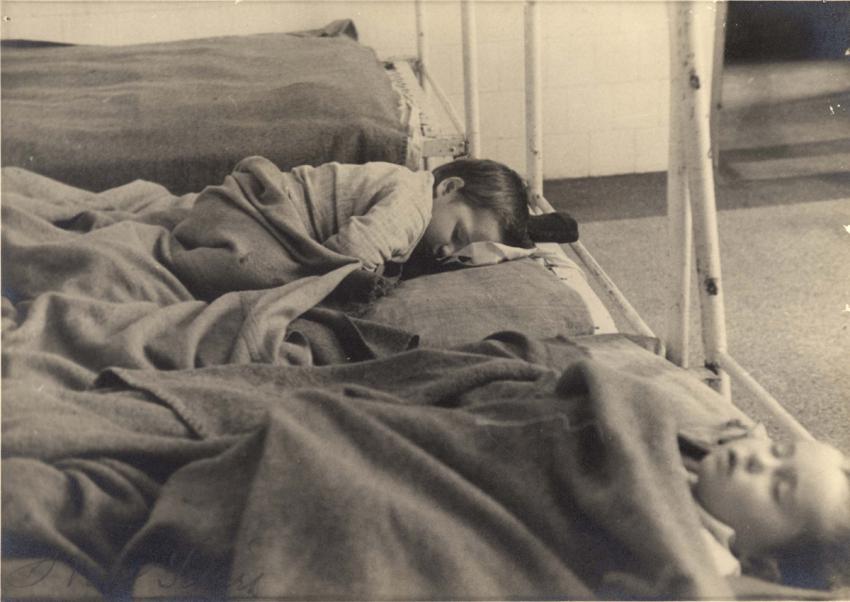

In this section we will focus on the reasons why Jewish children, who had been in the main traumatized by separation from their families and the hardships of the Holocaust, chose to identify with the Bericha movement. Did they know what Bericha was? Did they just follow everyone else, not knowing where they were going? How did the leaders of the Bericha approach them?

New Beginnings

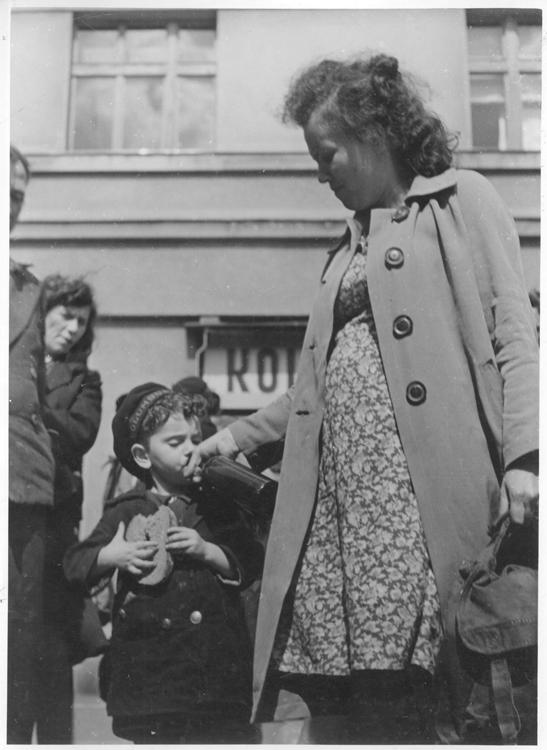

In liberated Poland, temporary orphanages and homes were set up for Jewish children in an attempt to restore some form of normalcy until they began their journey to Palestine, assisted by the Bericha movement.

Some children had become accustomed to their new lives, and did not wish to leave the families or homes they had been placed with, as they felt safe and secure. They wished to maintain their Christian identities and live in Poland. For example, when Marta Goren’s Grandfather Yitzhak found her, she growled, “get out of here. Why did you come? Go to where all the Jews went. We don’t want you here…”

Later, Marta, aged ten, was temporarily placed in a home for Jewish orphaned children in Poland, and slowly began to regain her Jewish identity. Marta recalls,

“..On a winter evening in 1946, the good woman woke us and instructed us to leave the house quietly. We were lifted onto a truck and ordered to be quiet. We drove all night and in the morning when the sun rose, the truck stopped in a forest. A young man stood in front of us. “We are on the way to Germany,” he explained. “But right now we are in Slovakia and we must cross another border. We took you out at night because the new regime in Poland limits the exit of Jews from the state. In Slovakia, the new regime also threatens the freedom of movement of Jewish people, and therefore we will wait here until evening, distribute food and when it is dark we will continue by truck. Do what you are told, and with G-d’s help, we will arrive safely.

At night we boarded the truck and drove in tense silence. Before dawn, and many hours later, the truck stopped. We immediately got off. The order circulated quietly – divide into pairs. The young people around us seemed to be in army uniform. Some spoke Polish and some spoke Yiddish. I realized that they had come to help us and I relaxed my guard. We marched in water in a river channel; the route was long and strenuous. I got wet, fell and hurt myself. When I was too exhausted to walk, one of the youths picked me up and carried me on his back. Towards morning, we were already in Germany. We boarded another truck and two hours later arrived at a children’s home in a Displaced Persons’ camp.”

Source: Naomi Morgenstern, The Daughter We Had Always Wanted – The Story of Marta, International School for Holocaust Studies, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 2007, pp. 84-85.

Some children accidentally encountered the Bericha movement as they wandered across Europe after the war, looking for family members or simply a place to live.

Eliezer Kristal, who was born in Poland in 1931, describes his feelings after liberation:

“We stayed in France for a certain period. We were housed in Paris in Rothschild’s house. It is a huge house. We were there for some time. During that period we learned the [Hebrew] language. Emissaries from Eretz Israel (pre-state Israel) came and told us about life there, we were going to live on a kibbutz. They told us about kibbutz life, we were drawn to it. But at that time there was a conflict in Palestine and we lived the conflict and felt the pain of loss of life. We wanted to get there as quickly as possible…”

Source: Y. Kleiman and N. Springer, The Anguish of Liberation - Testimonies from 1945, Aharoni (Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1995) pp. 42-43.

After liberation, 17-year-old Asher Oud walked to Hirsching where he found shelter in an abandoned house with 27 other Jewish children. The Jewish Brigade later took them to Santa Maria Di Bagne in Italy, where they learned Hebrew. In August 1945, they received certificates allowing them to immigrate to Palestine.

Turning Point

For many survivors, the turning point and decision to leave Europe came after the Kielce pogrom, in which 42 Jews were murdered by their former Polish neighbors in 1946. Survivors returning to their former homes felt estranged, unwelcome and in danger of their very lives.

Leon Faigenbam, a Holocaust survivor from Poland, relates his experiences:

“In Austria I registered with the Bericha for the illegal journey to Palestine. Through all my years of misery, I was convinced that a homeland would make it impossible for these things to happen again. The threats of the Polish AK (Armia Krayova) man justified my conviction, and my desire to fight for such a homeland became a burning one. I rejected an opportunity to go to the United States in favor of helping to win that corner of the world for ourselves.

At that time it was impossible to go directly from Austria to Palestine. Instead my wife and I with a small group, snuck out of camp each with a baby on our shoulders, and crawled over the mountains into Italy. From there we traveled by train to Genoa where we boarded a small fishing boat. The boat’s capacity was forty, but the Bericha loaded her up with two hundred man, women, and children…"

Source: Jacob Biber (Ed.), Studies in Judaica and the Holocaust, Nr. 9. “A Triumph of the Spirit”, The Borgo Press. p. 81.

In other instances, nuns in convents that had sheltered Jewish children during the war did not want to give them up, claiming the children were not Jewish. Too young to remember their real families, these children found the experience traumatic to say the least.

“On more than one occasion, government agencies and courts had to intervene in order to force nuns and adoptive parents to return children to their families. The story of the “convent children” who did not return to the Jewish fold is complicated and painful.

Suffice it to note that the difficulties that attended the matter in Poland were no different from those that surfaced in other European countries. The main difficulty was that the convents were not willing to return children to Jewish institutions that asked for them and refused to recognize them as the youngsters’ custodians.”

Source: N. Bogner, "The Convent Children”, in D. Silberklang (Ed.), Yad Vashem Studies XXVII, Jerusalem 1999, pp. 235-285. [Full article.]

Lost And Found

Ephraim Shtenkler was orphaned and spent time at the end of the Second World War in a children’s village in Poland. Shtenkler remembers:

“One day they asked which were the orphan children. I was among those children. Everyone wanted to know why they asked us this. Eventually we learned that we were going to be the first to go to Palestine. We were extremely glad. The children danced and sang. The next day all us orphan children got into a car and we rode to the railway station. We traveled in two groups to one of the places in Poland. Here something strange happened. We waited all night and the car didn’t turn up. Next day, everyone was in a state of confusion. The day after that, they fetched the group that had traveled with us and told us to wait another couple of days. At the end of these two days a car came and fetched us. We traveled for many hours; and meanwhile I slept.

Eventually we arrived. I heard shouts. There a small ship awaited us – I should rather say a large boat – and they put us all into it and we started off. The boat rocked on the surface of the quiet waves. All of a sudden the boat heeled over to one side. All the things on the top fell off but by a miracle we were saved. There was a certain soldier there from the Russian Army. He knew what to do in moments like this. And the day passed and it grew darker until night fell. We were sleeping and the soldier couldn’t sleep and went up on top and suddenly there was something shining in the water. He pulled out his revolver and took his torch and looked and saw and behold there were mines in an enormous line! In that instant he let out a yell. At the sound of that shout we all woke up. The pilot wanted to take the boat on a detour around Berlin and thus was about to run into the mines. But the man with his revolver in his hand leapt straight down into the engine room. He broke through the hatch and jumped on top of the pilot. The pilot started back and thought – bandits! He sat himself down in front of the soldier and steered the boat over many many kilometers to Berlin[..]

One fine day all of us orphans set out for Palestine. They told us many tales then – endlessly. They woke us up a midnight and the car came in the morning. Eventually we arrived at one of the camps. The next day we traveled and went on and on without end. But I remember that finally we came by train to France. I don’t remember the journey. It was for three days and three nights. From France we went on board a ship [..] how excited we were when at last we were assembled on parade and disembarked from the ship! And we came to Ahuza the children’s village on Mount Carmel and from there to the children’s village at Hadassim."

Source: L. Holliday, Children in the Holocaust and World War II, Pocket Books, New York 1995, pp. 28-30.

In spite of their personal loss, Eva and her husband were determined to get to Palestine.

A stray bullet had killed Eva Cherniak Biber’s young baby as she and her husband hid from a gang of Ukrainian militiamen in the forest. At the end of the war together with other survivors, they made their way from the Soviet Union back to their home town of Gliwice, Poland. Eva explains:

“The first day we were told of a “secret” Jewish agency, the Bericha, an organization which helped survivors to escape. We immediately got in contact with them and met the leader, a heroic young woman who had fought with her husband during the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. We began to make preparations for the illegal journey to Palestine. By then I was five months pregnant. I kept my pregnancy a secret from the Bericha, suspecting they would not let me make the dangerous journey in my condition. I was determined to escape from Europe if possible, and I knew Jake supported my decision.

We began our difficult trek by train through Czechoslovakia dressed as Greeks, then continued on foot, crossing a forest into West Germany. There we reached a camp for displaced persons, Camp Fohrenwald.”

Source: J. Biber (Ed.), Studies in Judaica and the Holocaust, Nr. 9. “A Triumph of the Spirit”, The Borgo Press, pp. 119-120.

During the three years following the Second World War, approximately 120,000-150,000 Jewish men, women and children left Eastern Europe with the aid of the Bericha movement.

Discussion Questions

- In your opinion, what gave the children the motivation to begin a new life in a new country? What do you think made Eliezer Kristal wish to leave Europe and immigrate to Palestine?

- Discuss a parent's dilemma when placing his/her child in a convent or with a family during the Holocaust period.