Grades: For high-school students, ages 17-18

In the following educational environment, we offer you a model of teaching a complex and morally difficult subject – that of the history of the Holocaust in the occupied Soviet territories. This subject is presented in more detail and in further depth on the "The Untold Stories" project website.

The environment will focus on the specific story of the city of Buczacz, Ukraine. Through the example of one city and one community, the key stages of the development of the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” in the former Soviet Union, as well as the striking phenomenon of a peaceful hometown becoming the mass-murder site of its own residents, are demonstrated. Materials from "The Untold Stories" site and from additional sources will be used.

Introduction

IntroductionMost people think of the Holocaust as an event of industrial killing, symbolized by Auschwitz: a vast undertaking of streamlined, anonymous mass murder. In fact, half of the total victims of what the Nazi called the “Final Solution of the Jewish question” did not die in extermination camps; they were killed in their own homes and streets, cemeteries and synagogues, in nearby hills, forests, and ravines. The killing was neither anonymous nor streamlined: the murderers often knew their victims by name and saw them face to face just before they shot them… The killers were not only German police and SS, or only German of any description, but also members of other ethnic groups from the victims’ own regions and towns, often people they had known for years as classmates and colleagues and neighbors. There was nothing secret about these events: they were public, routine spectacles in which everyone played one role or another.

1

In this apt description, Omer Bartov points to the unique characteristic of the Holocaust of the Jews in the Soviet Union (both on its original pre-war territories as well as on the territories annexed by it in 1939) – its local character. Indeed, the industrial, alienated, anonymous murder that occurred in the famous extermination camps led to the death of three million Jews. But for many of the victims, death was not detached from the structure of their normal life. It was not about being led systematically and abnormally to a place devoted specifically to taking lives. For many, death and life came to be intertwined and associated with the same places, landscapes and memories. The victims and many of the murderers – the collaborators with the Nazi regime – as well as those who came at times to the rescue of the Jews were not strangers: they knew each other from the local market, from the classroom, from the hospital or the railway station.

The story and destruction of the Buczacz community exemplify this uniqueness of the Holocaust in the USSR quite well. While some 4,000 local Jews were sent to the Belzec extermination camp comprising perhaps about one third of the Buczacz Jewish community at the time, the other two thirds were killed at various murder sites in the city's surroundings, i.e. near the cemetery where their ancestors were buried, and on the green hills where they used to wander and rest. The fabric of life and the relations between the Jews and their non-Jewish neighbors (some of Polish and some of Ukrainian national identity) surfaced in their full complexity during the war. The fact that the city passed from hand to hand several times during the war – from the Poles to the Soviets, from the Soviets to the Germans and eventually back to the Soviets undermined even further the interethnic relations in Buczacz. Through the story of one town, Buczacz, we hope to expose the learner to the broader phenomenon of murder sites in the former Soviet Union.

The Untold Stories Project

The invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany on June 22, 1941 (Operation Barbarossa), served as the beginning of the mass extermination of Jews in the occupied Soviet territories. The Nazi policy of destruction was motivated by two main ideological reasons – the colonialist character of the war (“Lebensraum” , or “Living Space”) and the fight against “Judeo-Bolshevism”.

During the war, many Jewish communities throughout the previously Soviet controlled areas were completely destroyed. The tragic end of many of the larger communities has been well documented and has consequently become well-known. However, the stories of hundreds of smaller communities who were murdered in killing sites across the former Soviet Union remained unaddressed and unknown.

"Untold Stories" project ("The Untold Stories: The Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR") is dedicated to the fate of these smaller communities. In this project run by the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem, researchers identify and scour through documents, photographs and testimonies with the aim of commemorating and sharing these untold stories.

In addition to providing background information on the communities themselves, "The Untold Stories" site also contains information on mass killing sites, where hundreds and thousands of Jews residing in these communities were murdered. This information includes testimonies – textual and video – of Jewish survivors, written accounts by local residents, reports of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission, and SS and Wehrmacht reports. A special place is given to descriptions of the local efforts to commemorate the murdered Jews.

- Omer Bartov, “The Voice of Your Brother’s Blood: Reconstructing Genocide on the Local Level,” in Jewish Histories of the Holocaust: New Transnational Approaches, ed. Norman J. W. Goda (New York: Berghahn Books, 2014), 104.

Buczacz until World War II

Buczacz until World War IIMy town lies on hills surrounded by and intertwined with rivers and lakes. Pleasant springs flow down to forests thick with trees and full of singing birds. Some of the birds are natives of the land; others are foreign and have chosen to stay, for only a fool would give up so blissful a paradise. Whoever can distinguish between the different bird songs can tell the native from the foreign birds.

The streets and avenues in the town lie in contrast to the hills. They are the work of both man and nature, each complimenting the other. This is one example where the makings of God and those of man join together peacefully in a complementary manner. One can imagine that those same streets and avenues go back to times when people’s hearts were pure and uncorrupted.

2

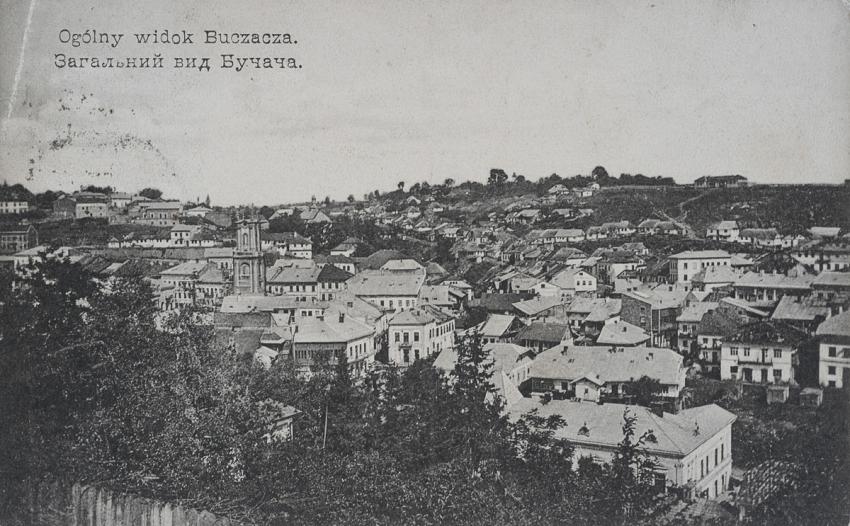

The town of Buczacz is situated on the banks of the Strypa River, a tributary of the Dniester, some 150 kilometers southeast of Lvov (today in Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine).

Human settlement in the area of Buczacz can be traced back to antiquity. In the late Middle Ages a typical fortress and a palace were built in Buczacz by the noble family of Buczaczki, and in the 16th century the urban settlement of Buczacz was established.

Evidence of a Jewish community in Buczacz can be found in documents from the beginning of the 16th century. In the middle of the 16th century, the Jewish population in the eastern regions of Poland (Volhynia, Podolia and the surrounding territories) where Buczacz is located experienced rapid growth. The Polish nobility encouraged the Jews to settle in the eastern regions of the Polish-Lithuanian state and to help further economic development in these regions. Thus, the Jewish community of Buczacz, whose legal and economic rights and obligations were regulated by the privileges granted them by the local noble landowners, grew and formed the basis of the urban middle class.

In 1648 Buczacz suffered from the raids of the Cossacks, although they were unable to actually conquer the town. A few years later, the town had to face the Tatar wars (1655-1667). However, life quickly returned to normal. Ulrich Werdum, who visited Buczacz in February 1672, wrote in his memoirs:

Buczacz is a large and amusing (“possierlich”) town spread over mountains and a valley with a lake to the West. The town is surrounded by a wall; its houses are well built. It has three Catholic churches and a Ukrainian monastery, now run by the Dominicans. The Armenians also have a church, and the Jews have a synagogue and a well-kept fence-encircled cemetery with beautiful large trees growing in it. The castle is made of stone, as are its fortresses. It lies on the top of the mountain where the Stripa River, originating from the village of Zlotnik 6 miles away, flows at its sides. The river supplies the power for 10 to 12 water-mills placed beside each other. The town of Buczacz is the estate of Lord Potocki. At the beginning of the raid, the Cossacks and the Muscals set fire to the whole town, which has now been rebuilt, especially by the Jews. They (the Jews) are numerous here, as in Poland and Belorussia.

3

However, soon enough Buczacz had to face a war with the Turks (1672-1675) who conquered substantial parts of Ukraine and laid siege to Buczacz. Most residents took shelter in the fortress but the town itself was destroyed and burned down. Those who hadn’t fled to the fortress were slaughtered.

In the following decades, we hear of the renewal of the Buczacz Jews’ privileges by the Potocki family with regards to trade, taxes and self-administration. Thanks to these, the Jewish settlement in Buczacz quickly recovered and developed economically.

In 1772, as a result of the first partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Buczacz was annexed to the Austro-Hungarian Empire as part of the larger region of eastern Galicia. According to the new regulations, the Jews who were not peasants were not allowed to live in the villages. The Jewish population of Buczacz increased as Jews from the nearby villages moved to the town.

Under the Austro-Hungarian rule, Buczacz underwent a number of processes that characterized to a large extent all of Galician Jewry and that affected the social and cultural fabric of the town. In 1787 the Jews were required to assume German family names, which marked the beginning of the Galician Jewry’s acculturation process. The Hasidic movement was on the rise in Buczacz and several Hasidic synagogues were established. At the same time there remained a strong nucleus of resistance (the mitnagdim) to the Hasidic movement with its cultural center in the Old Beit Midrash, located just by the Great Synagogue. In spite of some degree of animosity between these religious trends, we do not hear of outright confrontations between the Hasidim and the Mitnagdim. Nonetheless, as the Hasidic movement in Buczacz grew stronger in the mid-19th century there did occur a kind of conflict between the Hasidim and the Maskilim who were scornful of Hasidism. The conflict was reported to the local authorities.

The year 1848 was a turning point for the Jews. The Jews were granted full equality of rights with the non-Jews. This brought about changes in education and in the way the education process was conducted among the Jews. The ideas of the haskalahand cultural advancement became more and more popular.

Nonetheless, the traditional educational institution heder, in which the Torah and Judaism were studied, continued to function in Buczacz until its termination in WWII. The contents of these studies were quite diverse and adjusted to the different needs and to the parents’ preferences. In some of the Hadarim the students were required to study exclusively the traditional Judaic studies while in others the students could combine the Judaic and the secular studies in the appropriate institutions. There was a specific fund called the Talmud Torah fund to which the community members would make contributions which were used to finance the Judaic education of the needy.

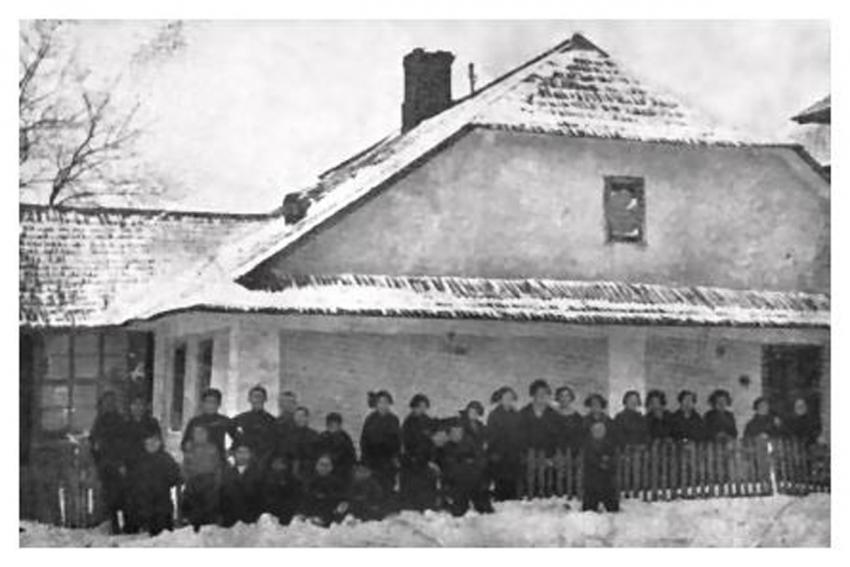

As time went by, most Jews began to combine the Judaic and the secular studies. Most Jews in Buczacz would send their children to the Baron Hirsch (Jewish) four-year general education elementary school established in 1892 while others would place their children in a local Polish school. After that some students would continue their education in batei midrash or the gymnasium while others would start working. In 1907 there were 180 students attending the Baron Hirsch School. In 1908 there were 216 Jewish students attending the gymnasium out of the total 696 students. The town’s maskilim also set up a general education library, the “beit midrash”, as well as a culture club that attracted many people and became a place of thriving intellectual and literary activity.

The rise of the Jewish national movement, the Zionism, since the 80s of the 19th century, played a central role in Buczacz. In 1893, the “Zion” association was founded in the town, and a general assembly meeting was held in April 1894, in which theoretical and practical ideas regarding the future of the Jewish people and its national revival were discussed. The Zionist ideas spread relatively widely among the Jews of Buczacz, and it became one of the most important Zionist centers in East Galicia.

With the outbreak of the First World War, peaceful and comfortable life in Buczacz came to an end. Many of the Jews, frightened at the approaching battles and the front line, had to flee away, and the economic situation deteriorated greatly. The peace was not restored immediately with the end of the World War I. The Jews of Buczacz suffered greatly during the calamities of the Soviet-Polish war (1920-1921), when for a short period the town came under the rule of Petliura's Ukrainian Army, which robbed, raped, and murdered Jews.

From 1921 Buczacz was part of the Second Polish Republic. During this period, life more or less returned to normal, although the Jewish community never recovered its pre-war status and prosperity.

Jewish religious, cultural and social activity continued in Buczacz until its destruction. As in other regions of the Second Polish Republic, there was turbulent political activity underway in Buczacz. Many parties, both religious and non-religious, Zionist and non-Zionist, took part in it.

Among the institutions in the Jewish community were an orphanage and an old-age home, a kosher slaughterhouse, a hospital (founded in the 17th century), religious and non-religious schools and youth organizations.

The Great Synagogue of Buczacz was inaugurated in 1728, after the previous synagogue was destroyed. It was a magnificent building designed by renowned Italian architects and with the support of the Potocki family. Having been burned down in the 19th century, it was subsequently rebuilt, renovated and served the Buczacz community until World War II. Besides the Great Synagogue, there were between twelve and fifteen other synagogues in Buczacz as well as more than thirty-five “Minyanim”(regular meetings/gathering for prayer in an unofficial synagogue building). Among these one can mention the “Old Beit Midrash”, a stronghold of the Mitnagdim and the synagogue of the Chortkiv Hassidim.

Buczacz is situated in a mountainous area on the banks of the Strypa. Many of the town's Jewish natives remember the beautiful natural sites that surrounded the town as well as leisure trips and activities in the green areas surrounding the town. Israel Cohen writes:

Buczacz – surrounded by mountains. One of these mountains is named Pedor. At its edge there was a forest. It was traditionally believed in town that the Frankists consulted secretly in the valleys and in this forest. This is where these zealots assembled prior to the famous public debate in Lvov. Under the shade of these trees they sharpened their blasphemous tongues, cursing the Jewish religion and libeling its leaders and their Torah. However, they were not the only ones who took refuge under the shady trees. Up on the plateau one could find innocent dreamers among the intellectuals, dreamers of new gods and reformers of the world. Throughout all the generations thinkers struggled with their thoughts in this forest. Hasidim, mitnagdim, intellectuals, anarchists, socialists and Zionists, including the youngsters of HaShomer HaTsair – the Zionist movement that was founded at the end of World War One. At dawn or at night, all would visit this forest, opening their hearts and roaring out the anguish of their troubled souls. Here merry and sad folksongs, songs of rebirth and hasidic songs were sung, planting seeds of joy in young Jewish souls. A net of legends and events spread before the hiker along the paths of the mountain and forest. Desires and dreams from the past, not yet extinguished, were secretly reincarnated within him. A sense of something not yet brought to completeness always filled the air of this pleasant place. The winds that blew there would grow sevenfold, rain stormed frequently and whoever walked alone there would, against his will and despite the spacious and colorful scenery around him, fall into deep sadness. However, during those wonderful sunny days when nature displayed a scented green landscape across the plateau and down its slopes, the music of the forest resounded everywhere and Jewish young men and young women strolled off to read Jean Cristophe [Romain Roland's romantic novel] and returned full of faith in man and his world.

4

Many notable and renowned figures were born or resided in Buczacz. Among the rabbinical figures one can mention Rabbi Meshulam Igra (1752-1801), a prominent Torah scholar who was born in Buczacz, and Rabbi David Avraham Wahrman (1771-1840), a famous scholar and writer, who was also a Hasidic Rebbe, and served as the rabbi of Buczacz from 1814 until 1840.

A famous Jewish historian Emmanuel Ringelblum known for the so-called Ringelblum's Archives of the Warsaw Ghetto who was born in Buczacz in 1900. The famous Nazi-hunter Simon Wiesenthal was also born in Buczacz in 1908.

Above all Buczacz became quite famous thanks to one of its most illustrious sons, Shmuel Yosef Agnon, a world renowned writer and a Nobel Prize laureate. Born in Buczacz in 1887, Agnon conveyed to his readers much of its scenery, colors, smells and atmosphere.

- S.Y. Agnon, ‘The picture of the Town’, translated by Adam Prager, in Yisrael Cohen (ed.) Buczacz Book (Translation of the Memorial (Yizkor) Book of the Jewish Community of Buczacz, Galicia), New York: JewishGen, 2013.

- Xawery Lisicki, Cudzoziemcy w Polsce. Lwow, 1876, p. 182.

- Israel Cohen, ‘The Buczacz Community’, translated by Adam Prager, in in Yisrael Cohen (ed.) Buczacz Book (Translation of the Memorial (Yizkor) Book of the Jewish Community of Buczacz, Galicia), New York: JewishGen, 2013.

During the War: The Murders

During the War: The MurdersWhat was the scope of the Holocaust in Buczacz and where did it take place?

On the eve of the war there were perhaps some 7,500-8,000 Jewish residents in Buczacz constituting slightly over half of the town’s population.

Chronology of the Holocaust in Buczacz:

Aug 25 or 26, 1941, The First “Registration” - 350-600 Jewish men shot

From Dec 1941 - Jews being sent to labor camps

Before Passover 1942 - 150 artisans deported never to return

Oct 17, 1942 1st Action - 1,600 sent to the Belzec death camp, 200 shot in Buczacz

After 1st Action- 80 Jews brought to Czortków, most died

Nov 27, 1942 2nd Action- 2,500 sent to Belzec, 250 killed in the town

Dec 1942 - ghetto set up in Buczacz

Dec 1942-Jan 1943 - continual individual killings of the Jews occur in Buczacz and many Jews are brought to Czortków to die of hunger and disease

Feb 2, 1943 3rd Action - 3,600 are captured; most shot at Fedor; 85 children killed in the town

Feb-March 1943 - individual killings occur

April 13, 1943 4th Action - 2,800-3,600 murdered in three days

June & July 1943 Jewish labor camps liquidated including the Czortków area

May 15, 1943 - Buczacz is declared free of Jews (Judenrei or Judenfrei), rest of the Jews are transferred or escaped

March 23, 24, 1944 First takeover of Buczacz by the Soviets - 800-1,000 Jewish survivors come out of hiding but get murdered as the Germans retake Buczacz.

July 21, 1944 Final liberation by the Soviet army

Estimated total number of victims: ca. 12,000, 4,000 killed in death camps, 8,000 killed locally

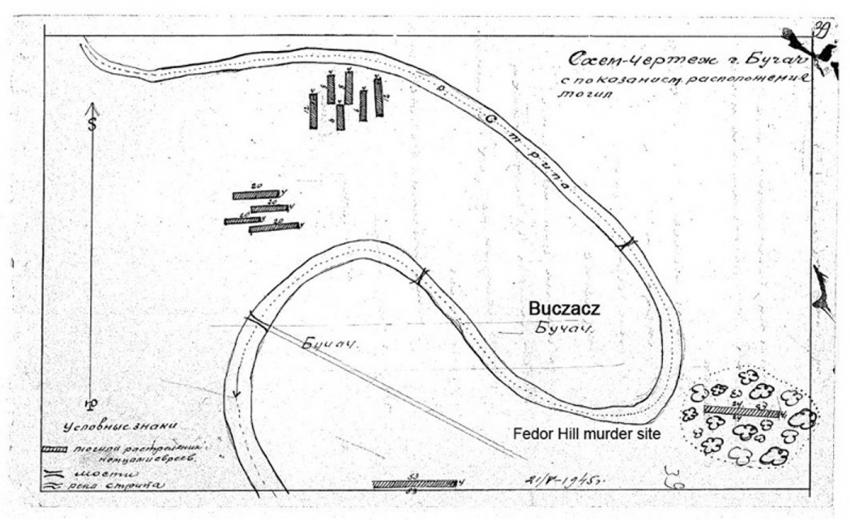

From the above figures we see that only about one third of the Buczacz Jews (and of the Jews transferred to Buczacz) were killed in the death camps whereas the other two thirds were shot in Buczacz itself or in its vicinity. During the investigation carried out by the Soviet authorities in Oct-Nov 1944, 7,000 corpses were excavated in the mass graves on Fedor and Bashty hills (see the map).

Another murder site is the Lesniczowska Forest located some three kilometers away from Buczacz. In it two German Gestapo officials and the Ukrainian militia executed 40 Jews and non-Jews collected from the city’s prison.

Ten to twelve thousand Buczacz Jews were killed in the period between August 1941 and May 1943 when Buczacz was declared "free of Jews" (Judenfrei). Thus the Holocaust of the Buczacz Jews was happening for almost two long years not only in concentration camps but also in their own familiar surroundings, their hometown, among their neighbors and people they had personally known for years. There was no possibility for anyone to stay out of it. Both children and adults, the Ukrainians and the Poles were all involved in one way or another to one extent or another in the tragedy that unfolded in Buczacz.

How did the Holocaust unfold in Buczacz?

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, some of the Jews left Buczacz with the Soviets as the Red Army retreated.

The town fell into the hands of Ukrainian ultra-nationalists after the Soviet army had left and before the Germans arrived. The Ukrainian self-formed militia committed robberies and murdered eighty five members of the cooperatives established by the Soviets. They levied a 200,000 ruble contribution on the Jewish community.

The Jews were marked and their freedom severely restricted. The possessions of the Jews were expropriated and heavy contributions were levied upon them. Plundering the Jews was an important element of the Nazis' wartime economy. To some extent it helped them keep inflation down.

By the end of July the Germans ordered that a Judenrat (Jewish council) be established through which the Nazis could communicate their orders to the Jewish community. A Jewish police force (Ordungsdiesnt) as well as a labor bureau (Arbeitsamt) were set up in accordance with the general pattern in occupied Poland.

The evaluation of the Judenrat's and OD's role in the events that ensued differs from witness to witness. Collaboration with the Nazis as well as assistance to the Jews and active and even heroic resistance to the Nazis are attested.

The First "Registration"

On August 11, 1941, all Jewish men were summoned up for "registration." No executions occurred this time for some uncertain reason. Perhaps the Nazis wanted to create an impression that there was no danger in showing up for a registration. The men were allowed to return home. However, two weeks later, on August 25 or 26, all the men aged 18-50 were gathered again and some 350-650 of them were selected and shot on Fedor Hill. The perpetrators were a German police unit and the Ukrainian militia.

Question:

- What principle do you think the perpetrators used in selecting the victims?

Unlike in the subsequent 'actions', the details of the first mass shooting of the Jews on Fedor, are cloaked in darkness. The family members of the victims were trying their best to find out what had happened to their family members but to no avail. Alicia Appleman-Jurman went searching for her father everywhere on Fedor Hill but couldn't find any traces of the victims.

Isaac Shikhor and other children's attempt to locate the whereabouts of their family members almost cost them their lives:

The next day I, and some other children, sneaked out of our homes. We climbed up to the 'Fedor,' where some of us looked for their father, some for their brother, and some for other relatives. This exploration almost cost us our lives. When we approached the forest, an armed Ukrainian policeman burst forth suddenly from behind one of the trees, and he asked us why we were walking about in the forest. We answered that we were searching for members of our families who had been taken away from us the day before. The policeman smiled and 'promised' to bring us to them. Who knows how this matter would have ended, had not the forest guard appeared suddenly and asked the policeman to let us go home. Obviously I did not tell anyone at home about this adventure in the forest.

21

Question:

- why do you think the first execution of the Jewish men on Fedor was secretive while all the subsequent “actions” more public?

First Action

Murders on a small scale occurred between the German occupation in the summer of 1941 and October 1942. On October 17, 1942, the Gestapo carried out an action in Buczacz sending some 1500-1600 Jews to the Belzec camp. Hundreds of Jews were simply executed in their houses in the course of the action. Babies were brutally murdered. The action included, of course, an economic element as well: the Jews' belongings were confiscated. Below is an excerpt from Samuel Rosenthal's testimony:

On the seventeenth of October 1942, the Gestapo (with the help of the Jewish militia) descended upon the houses of the Jews and brought more than 1500 Jews to the "May Third Plaza." From there they were put on railroad cars and sent to Belzec. After this actzia, four hundred bodies were found in the houses and they were buried in a mass grave in the Jewish cemetery. In Yaakov Margaliot's yard, they found eighty-five babies whose skulls have been crushed. Every day, the Hitlerite beasts stole babies from their mothers, crushed their skulls and threw them onto piles. They were brought to a mass grave in the Jewish cemetery in four wagons. At the same time, other Jews were forced to gather the belongings of the murdered and deported Jews, and bring them to the Germans' warehouses.

22

Question:

- Why do you think it took the Nazis and their collaborators over one year to restart their large-scale actions against the Jews in Buczacz?

Second & Third Actions in Nov, 1942 and Feb, 1943

Elyash Khalfan describes how people ran for life as another action was imminent and how the weak, the sick and the poor bore the brunt of the action. The sick were often abandoned while the poor and the Jews who arrived in Buczacz from other places could not hide effectively from the police that ransacked the houses and the buildings:

On the evening of November 24, 1942, a rumor made the rounds that an Aktion was about to begin. Almost everyone went to his hideout while some fled to nearby villages. Everyone worried about his own safety, without regard for that of others. The sick were left without help and the first shots heard the following morning signaled their death. The Aktion lasted all day. Some 1200 persons were arrested, mostly the poor people whose lot it had been to dwell in synagogues or house ruins upon coming to the Ghetto. None were able to escape from the train wagons carrying them to Belzec as they were searched while still in the station and any object of potential use in an escape was confiscated.

23

Other testimonies have higher figures of the Jews shipped to Belzec. It is possible that between 2,000 and 2,500 Jews were put on the train to the death camp while another 250 were shot in the town during the second action.

In the third action on Feb 2, 1943 between 1,400 and 3,600 Jews were shot at Fedor and buried in the pits dug there beforehand.

Gelbert testifies in his testimony that the behavior of the non-Jewish population with regards to the Jews changed depending on which way the wind was blowing in the fight between the Wehrmacht and the Allies. The Jews drew their hope from the news about the successes of the Allies at the front when the fourth Aktion occurred.

Fourth Action

At the beginning of April 1943, there was another Aktzia, in which several hundred Jews were killed. Several Jewish families were hiding in the home of a German in Naguzniki. Their presence was discovered and among those killed were Dr. Isidor Neuman, a Buchach lawyer, Sami Angelberg, and others. The surviving Jews drew hope from the news about Allied victories in North Africa and elsewhere. People speculated that there would be Allied advances from one side and Russian advances from the other and this gave them hope. The behavior of the non-Jewish population towards the Jews also varied with the news from the front.

28

Liquidation of the Ghetto in June 1943

The Ghetto was liquidated in June 1943 and Buczacz was pronounced Judenfrei (free of Jews). As the Red Army entered Buczacz on March 24, 1944 some 1,000 Jews came out of hiding or returned to the town. But the relief was temporary. The Soviets were driven out by the Germans and the nightmare visited the Buczacz Jews again. After four more months of the Nazi occupation the number of survivors dropped to some 100 Jews.

- Yehuda Bauer, "Buczacz and Krzemieniec: the story of two towns during the Holocaust." Yad Vashem Studies 33 (2005):245-306, at 248; Omer Bartov, See Bartov, "Genocide in a Multiethnic Town: Event, Origins, Aftermath." In: Baratieri, Daniela, Mark Edele, and Giuseppe Finaldi, eds. Totalitarian Dictatorship: New Histories. Routledge, 2014, 212-231, at 212. Precise figures are hard to determine. According to the 1931 census there were 7,000 Jews in Buczacz (Omer Bartov, “Interethnic Relations in the Holocaust as Seen Through Postwar Testimonies: Buczacz, East Galicia, 1941-1944.” Lessons and Legacies VIII (2008):101-124, at 111). The figure 8,000 is based on the census carried out by the Soviets just before their retreat in 1941. It is cited by the mayor of Buczacz Ivan Bobyk (see Bartov, 2008:122 fn. 13).

- Israel Gelbert, Buczacz Book,...; Horn Mates, Testimony of Horn Aharon Mates regarding his experiences in the Buczacz Ghetto and the Gleboczek labor camp, The Central Historical Commission of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the U.S. Zone, copy YVA M.1.E/3541236, p. 1.

- Bauer (2005:248).

- Ibid., 280-294.

- Report of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission (ChGK), Buczacz GARF 7021-75-371 copy YVA JM/19988, pp. 1-2.

- The Untold Stories: the Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former USSR. Yad Vashem.

- Bauer (2005:277).

- Ibid., 277; Yitzhak Borenstein, Buczacz Book, 300.

- Bauer (2005: 277).

- Ibid., 277-8.

- Ibid., 279.

- Ibid., 279.

- See Bartov (2014: 213-214).

- bid., 213.

- Bauer (2005:280); Bartov (2013: 212).

- Alicia Appleman-Jurman, Alicia: My Story, (Bantam Books 1990), 19-21.

- Isaac Shikhor, Buczacz Book, 239.

- Shmuel Rosenthal, Buczacz Book, 260 (Translated by Israel Pickholtz).

- Elyash Khalfan, Buczacz Book, 266 (Translated by Alejandro Landman and Norbert Porile).

- Bauer (2005:289).

- Ibid., 290. Testimonies differ as to the numbers of victims in this action.

- Ibid., 290.

- Elyash Khalfan, Buczacz Book, 266 (Translated by Alejandro Landman and Norbert Porile).

- Israel Gelbert, Buczacz Book, 280.

The War: Relations between the Jews and the Non-Jews

The War: Relations between the Jews and the Non-JewsWhat were the causes of interethnic tensions in Buczacz?

Buczacz was a shtetl: it was a town with a Jewish majority and substantial Polish and Ukrainian populations whereas in the surrounding villages as well in the east Galician region in general the Ukrainian population was predominant. Although residents of Buczacz testify to good neighborly relations between the Jews and the non-Jews, the multi-ethnic makeup of Buczacz "meant that the German genocide of the Jews took place within a complex and increasingly volatile web of ethnic, religious, political and national affiliations."

The nationalist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries played a major role in creating interethnic tensions in Buczacz and in eastern Galicia in general. Both the Poles and the Ukrainians claimed that they were the aboriginal population in the region. When, in the wake of WWI, eastern Galicia became part of the newly established Polish state, the Polish government was interested in populating the region with more ethnic Poles so as to counterbalance the Ukrainian majority.

The Ukrainians were provoked by the Poles' failure to grant them autonomy. The tension between the Poles and the Ukrainians grew and, as a result, the Ukrainian nationalist movement became extremely radicalized. The radical Ukrainian nationalist ideology sought to establish a Ukrainian state free of other ethnic groups, namely free of both the Jews and the Poles.

The Ukrainian nationalist movement was in conflict not only with the Polish nation building but also with the communist ideology of the Soviet state. When the Soviet Union and Germany divided the territory of Poland based on the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, the Soviets harshly persecuted the Ukrainian nationalists. As a result the Ukrainian nationalists chose to ally themselves with the Nazi Germany hoping to fulfil their nationalist aspirations by collaborating with the Nazis.

With the arrival of the Nazis the interethnic tensions built up prior to the war broke loose. As described in the previous section, the Ukrainian nationalist militia quickly filled the vacuum created by the withdrawal of the Soviets from Buczacz and started their anti-Jewish activity even before the German forces arrived.

The Nazi propaganda emphasized the leading role of the Jews in the Bolshevik communist movement. Some of the Jews indeed participated in the Soviet government and many were conscripted into the Red Army. This was true for Buczcaz as well as for other places. The Germans utilized the Ukrainian nationalists' resentment of the Soviet regime and channeled their rage against the Jewish population as being allegedly the leading force behind Judeo-Bolshevism.

Apart from the bigger ideological factors, sheer human selfishness, greed, envy, and self-preservation instinct constituted a major factor in the Holocaust in Buczacz as well as in other places.

There were surely instances of rescues as well as those of betrayal. However, that the instances of rescues were heavily outweighed by those of betrayals is clearly evidenced by the appallingly low numbers of the Jewish survivors in Buczcacz. Only some 100 out of 10,000-12,000 Jews in Buczacz survived the Holocaust. Only about one third of these Jews were killed in death camps. The others were murdered locally in Buczacz and its vicinity.

The Jewish and non-Jewish testimonies present somewhat different perspectives of what happened:

Gelbert testifies that prior to the war the relations between the Jews and the non-Jews in Buczacz were non-violent. This radically changed with the Nazi invasion:

The Jewish and non-Jewish populations had good, and even friendly, relations before the War (at least in comparison to other places in eastern Galicia).

The Ukrainians completely changed their relationship with the Jews and started to abuse them at every opportunity. If they happened to spot a prosperous Jewish home they broke into it at night and stole its contents. Often, the residents were taken to the Fedor and killed. Many Jews were murdered in this manner, under the eyes of the complicities Ukrainian leadership and “intelligentsia”. Among others, those killed included the tailor Kruh, Israel Landman, the wife of Dr. Foks, and the shopkeeper Polak.

32

Maria Khvostenko presents a different perspective of what happened between the Jews and Ukrainians:

From about the fall of 1942 to the end of 1943 they [the Germans] would hold akcja-shootings, always on Fridays…. On Tuesday evenings the Jewish militia would collect jewels and other valuable things…. On Thursday evening the [Germans] would come…. They would "act" or "work" all night, and the next morning as we were running to school we could see the results of their work: corpses of women, men, and children lying on the road. As for infants, they would throw them from balconies onto the paved road…. It was not hard to guess what was happening on Fedir Hill: we could hear machine-gun fire.

33

In her testimonies she refers consistently to the Germans and the Jewish police as the perpetrators and collaborators with the perpetrators. Yet she omits the decisive role played by the Ukrainian police and militia in the executions.

Non-Jewish witnesses interviewed 60 years after the war tended to obscure the role played in the murders by the local non-Jewish population. Responsibility is often placed exclusively with the "Germans" or the "Hitlerites":

"the Hitlerites committed crimes against the Jews . . . those people dug their own graves . . . they buried them alive . . . and … the ground was moving over the people who were still not dead.”

35

Julia Trembach who personally helped the Jews testifies that Ukrainians and Poles alike did their best to help the Jews survive:

"… our people – Ukrainians and Poles alike – tried to help them [the Jews] however they could. They made dugouts in the ground, and the Jews hid there. Secretly people would bring food to those dugouts. And God only knows how much food I myself brought."

36

Julia Trembach mentions a specific instance when she took in a young woman and breastfed her baby:

"[A young woman] was crying and exhausted. She whispered: 'Save us, hide us.' At my own risk I hid them in the loft of the cowshed. … I fed that little girl with my own breast, because I had a baby myself… and I shared my own food with that woman."

Shosh Kremer’s movie relating the story of her almost entire family’s extermination in the Holocaust in Buczacz includes a moving encounter between her father and his rescuer Karola Lekhka:

- Omer Bartov, "The Voice of Your Brother's Blood: Reconstructing Genocide on the Local Level." In: Jewish Histories of the Holocaust: New Transnational Approaches. Edited by Norman J.W. Goda (Berghahn, New York & Oxford 2014),104-134, at 107.

- Bartov, Omer. "On Eastern Galicia's Past & Present." Daedalus, Vol. 136, No. 4, On the Public Interest (Fall, 2007), 115-118, at 116.

- Omer Bartov, The Voice of Your Brother’s Blood, Brown University Jul 11, 2017, at 38:00-40:00.

- Gelbert, Buczacz Book, 272 (translated by Alejandro Landman and Norbert Porile).

- Cited in: Omer Bartov (2008:108).

- Ibid.

- Julija Mykhailivna Trembach, written on her behalf by her daughter, Roma Nestorivna Kryvenchuk, in 2003, collected by Mykola Kozak, translated from Ukrainian by Sofia Grachova. Cited in: Omer Bartov, "Communal Genocide: Personal Accounts of the Destruction of Buczacz, Eastern Galicia, 1941-1944." Shatterzone of empires: coexistence and violence in the German, Habsburg, Russian, and Ottoman borderlands. Edited by Omer Bartov and Eric D. Weitz. - Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013:399-420, at 404.

- Julia Mykhailivna Trembach's testimony cited in: Bartov (2008:101).

- Ibid., 102.

- Alicia Appleman-Jurman (1990:199).

- Omer Bartov (2013:406).

- Ibid., 219ff

- Bartov (2008: 109).

Post-War and Commemoration

Post-War and CommemorationWhat was the attitude of the Jews to the familiar environment of Buczacz?

The few Jews who returned to Buczacz following its recapture by the Soviets left soon thereafter. Some accounts have it that these Jews were all living in one building for fear of attacks. Places where the Jews as well as other residents of Buczacz used for recreation and leisure stirred up painful associations. A fourteen-year-old girl describes how the picturesque pastoral Fedor Hill, a former place of recreation and walks in the forest, has become a grave:

Grandmother was killed during the third massacre, and she is buried on Fedor in Buczacz. Where once people took walks, now there are 8000 murdered Jews. Together with Grandmother, we lost Devorah from Potok, and Aunt Esther with her husband and children. Not one of our relatives remains alive.

42

Shosh Kremer, who was born in Buczacz, lost many family members. She expresses her estrangement to her hometown which reminds her of the family that she lost and never had a chance to know:

I do not miss the town that I was born in; rather I miss my family, the grandfathers and the grandmothers, uncles and aunts - the family, my own family that I never got a chance to know.

43

Mina Rosner, a Holocaust survivor from Buczacz, returned to Buczacz when it was retaken by the Soviets but she felt that there was really nothing left in Buczacz to keep her there. Other Jews were leaving and Mina joined them.

The attitude of the Jewish survivors towards their non-Jewish friends even if those had not betrayed them was characterized by distrust since often one or more members of their friends' families collaborated with the Nazis as can be seen in Alicia Appleman-Jurman's relationship with her non-Jewish friend Slavka.

The Red Army entered Buczacz on March 23, 1944 but was forced out of the town by a German division passing through Buczacz as it retreated. In the short interval that the Red Army was in Buczacz some of the Jews felt free to leave their bunkers and hiding places and to show up in the town. Alicia Appleman-Jurman was among those returning to Buczacz. She met her Ukrainian friend Slavka and was invited over for dinner. The dinner was tense and overshadowed by Slavka's family's possible involvement with the Nazis:

If meeting Slavka had been difficult, it couldn't compare to dinner that night at her home. The family behaved as though they were afraid of me, especially Slavka's brother, Pavlo. He and my brother Herzl had gone to school together and had been friends, but he might have been the friend who betrayed Herzl. I could not bear this thought and forced myself to think of something else.

45

Commemoration

There are no traces of the great synagogue inaugurated in 1728 or the beit hamidrash torn down in 2001. No sign of the Jewish hospital is left. Very few traces of the once rich Jewish life can be seen. The only public recognition of the Jewish past of the town is the renaming of the street where Shmuel Yosef Agnon once lived after him. The commemorative plaque on Agnon’s house, however, does not mention that he was Jewish or that he won the Nobel Prize for Hebrew-language literature:

David Ashkenazi who survived the Holocaust and became a general in the Red Army is known in the town. Emanuel Ringelblum, creator of the Warsaw Ghetto archive and Simon Wiesenthal, a famous Nazi hunter, on the other hand, are completely unknown in Buczacz.

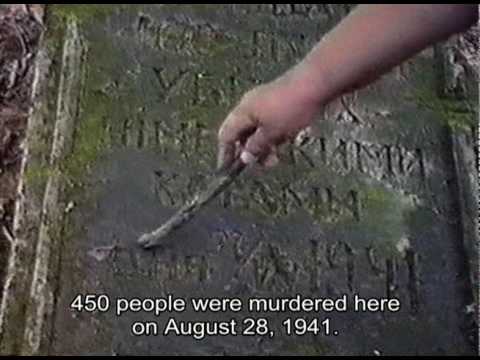

On Fedor hill where thousands were executed there is a small monument commemorating the murder of 400 "people." The monument was lying broken until 1990s when it was restored. It is located in the forest and is not visible to the public. The monument does not specify that these 400 victims were Jews:

Ironically, there is also a prominent monument commemorating the deaths of Ukrainian UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) and OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) members at Fedor.

The old Jewish cemetery is still found on the Bashty Hill albeit in a poor condition. Agnon's father's grave (Shalom Mordechai Czaczkes) can still be found among the graves. The slope of the Bashty Hill was the site where thousands of Jews were killed. The few remaining survivors put up a memorial after the liberation but the memorial has disappeared.

At the Holon cemetery, an annual memorial is conducted by the second and third generation descendants of the Buczacz Jews.

- Shoah Echoes in Buczacz, Buczacz Book, 297 (Translated by Jessica Cohen).

- Film produced by Shosh Kramer Tana: YV/ 3931 at 01:08-01:18.

- Mina Rosner, I am a Witness, (Hyperion Press Limited, Winnipeg, Manitoba 1990:104).

- Alicia Appleman-Jurman, Alicia: My Story, 211.

- See: Bartov (2008:103-106).

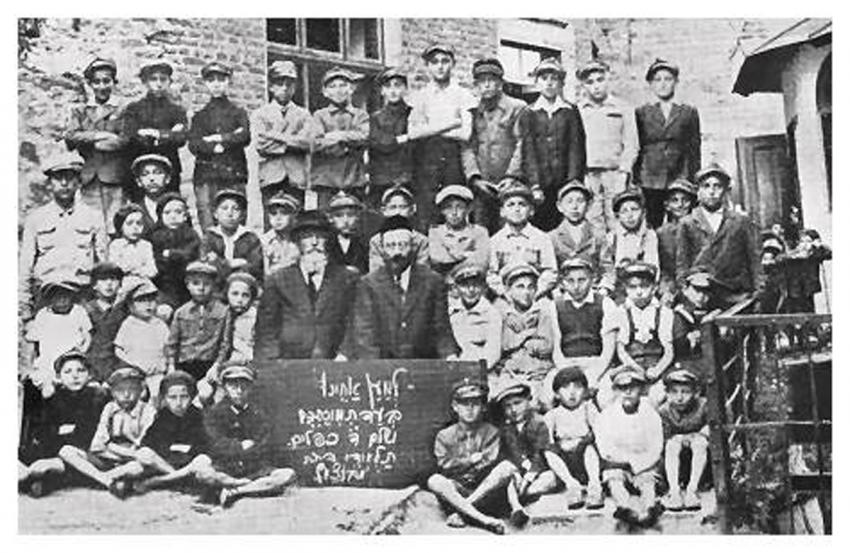

![The “Hechalutz” [the Pioneer] Organization in Buczacz in 1930 (source: Buczacz Yizkor Book) The “Hechalutz” [the Pioneer] Organization in Buczacz in 1930 (source: Buczacz Yizkor Book)](https://www.yadvashem.org/sites/default/files/styles/main_image/public/buczacz5b.jpg?itok=epg8sIxK)