Children and Their Diaries During the Holocaust

Between 1939 and 1945, six million Jews, including one-and-a-half-million children and teenagers, were murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. According to Nazi racial ideology, all Jews regardless of age were deemed unworthy of life.

The Holocaust was a period in which Jews were robbed of all liberties. They were starved, beaten, forced into hard labor, packed into closed ghettos, and murdered. Those still alive faced a daily struggle for survival. Despite and perhaps because of these hardships, we see a phenomenon of widespread diary writing, as well as personal and organized documentation efforts. The children, like all Jews, faced similar hardships, and many of them kept diaries as well. Due to the nature of war, only a very few of these personal accounts survived.

Overall, these children enjoyed a relatively normal, worry-free childhood before the Second World War. Whether from Poland, Germany, The Netherlands, Hungary or Lithuania, they were born into Jewish communities that had existed in Europe for thousands of years.

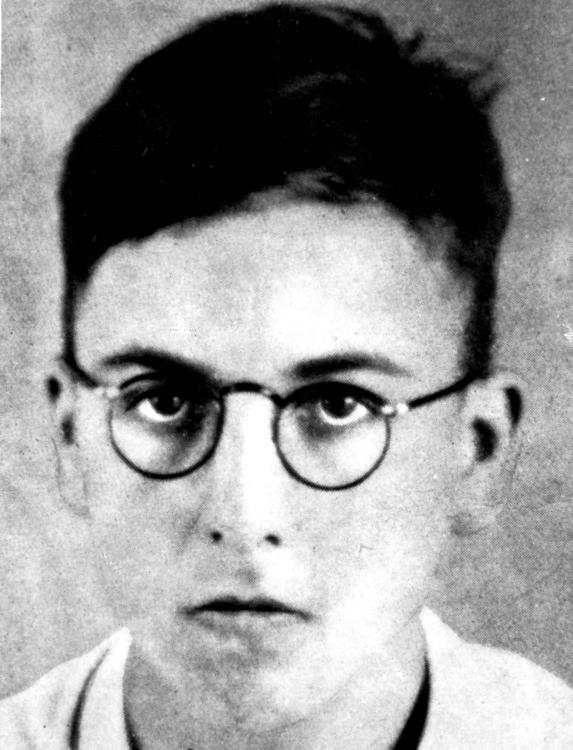

One these children was Moshe Flinker. Moshe Ze’ev Flinker was born in The Hague, The Netherlands, on October 9, 1926, and was eventually murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. In 1942, after the Germans and the Dutch police began rounding up Jews for deportation, he fled along with his family to Brussels, Belgium, where the 16-year-old Moshe kept his diary. He writes:

November 24, 1942

"For some time now I have wanted to note down every evening what I have been doing during the day. But, for various reasons, I have not got round to it until tonight. First, let me explain why I am doing this – and I must start by describing why I came here to Brussels.

I was born in The Hague, the Dutch Queen’s city, where I passed my early years peacefully. I went to elementary school and then to commercial school, where I studied for only two years .”

Discussion Questions

- We can estimate Moshe’s motives for writing the diary:

- Why does someone keep a diary?

- Do you think Moshe’s motives for keeping a diary were similar to those of children today?

Eva Heyman was born in 1931 in Nagyvárad, Hungary. She was murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in 1944. Early in her diary she describes her thirteenth birthday, and lists the presents she received:

February 13, 1944

“I’ve turned thirteen, I was born on Friday the thirteenth. [..] From Grandpa, [I received] phonograph records of the kind I like. My grandfather bought them so that I should learn French lyrics, which will make Ági [mother] happy, because she isn’t happy about my school record cards except when I get a good mark in French [..] I do a lot of athletics, swimming, skating, bicycle riding and exercise. [..] I’ve written enough today. You’re probably tired, dear diary.”

Discussion Questions

- What can we learn about Eva’s life and family from this excerpt? How would you describe her?

- How do you think Eva perceives herself?

To the teacher: This excerpt portrays Eva’s rich cultural and personal background – a thirteen-year-old girl with varied interests and hobbies. She has a supportive family, which encourages Eva in her activities.

The Onslaught of Nazi Occupation

The children’s daily routine was disrupted with the Nazi occupation. Although the Germans began to target Jews for persecution, the situation differed from country to country and region to region.

March 19, 1944

“Dear diary, you’re the luckiest one in the world, because you cannot feel, you cannot know what a terrible thing has happened to us. The Germans have come!”

Dawid Sierakowiak was born in Lodz, Poland in 1934. He perished in the Lodz ghetto, a victim of starvation and illness. In his diary, he describes hearing the Germans have entered Lodz:

September 8, 1939

“Lodz is occupied! The beginning of the day was calm, too calm. In the afternoon I sat in the park and drew a sketch of a girlfriend. Then all of a sudden the terrifying news: Lodz has been surrendered! German patrols on Piotrkowska street. Fear, surprise [..] Meanwhile, all conversation stops; the streets grow deserted; faces and hearts are covered with gloom, cold severity and hostility.”

Yitskhok Rudashevski was born in Vilna (now Lithuania) in 1927. He eventually perished in Ponary.

In 1941, the Nazi’s captured Vilna. Fourteen-year-old Yitskhok writes:

June 1941

“Monday was also an uneasy day. Red Army soldiers crowded into autos are continually riding to Lipovke. The residents are also running away. People say with despair that the Red Army is abandoning us. The Germans are marching on Vilna. The evening of that desperate day approaches. The autos with Red Army soldiers are fleeing. I understand that they are leaving us. I am certain, however, that resistance will come. I look at the fleeing army and I am certain that it will return victoriously.”

Discussion Questions

Read the following descriptions:

- How would you characterize the different reactions to the invasion?

- What do these reactions tell us about the children’s view of the situation?

To the teacher: with the outbreak of the war, many Jews hoped and believed it would end quickly.

First Decrees

Throughout Europe, persecution of the local Jewish population began swiftly after the entry of the Nazis. Jews were often stripped of their citizenship and barred from public institutions. Severe limitations were placed on their economic activity, and many became unemployed and destitute. For the children, school was disrupted and often halted altogether, and many Jewish pupils were forced to support their families by working or smuggling.

Eva Heyman, 13, Nagyvarad, Hungary:

April 7, 1944

“Today they came for my bicycle. I almost caused a big drama. You know, dear diary, I was awfully afraid just by the fact that the policemen came into the house. I know that policemen bring only trouble with them, wherever they go. [..] So, dear diary, I threw myself on the ground, held on to the back wheel of my bicycle, and shouted all sorts of things at the policemen: “Shame on you for taking away a bicycle from a girl! That’s robbery!” [..] One of the policemen was very annoyed and said: “All we need is for a Jewgirl to put on such a comedy when her bicycle is being taken away. No Jewkid is entitled to keep a bicycle anymore. The Jews aren’t entitled to bread, either; they shouldn’t guzzle everything, but leave the food for the soldiers.”

Moshe Flinker, 16, Belgium:

November 24, 1942

“During the year I attended, the number of restrictions on us rose greatly. [..] we had to turn in our bicycles to the police. From that time on, I rode to school by street-car, but a day or two before the vacations started, Jews were forbidden to ride on street-cars.”

Discussion Questions

Eva and Moshe are describing a process in which their daily life is becoming more constricted.

- What messages are these children receiving from their neighbors? How did the children experience the changes occurring in their environment?

To the teacher: In the students’ answers, direct them to Eva’s instinctive reaction towards the policemen, her protest when they take away her bicycle, and the response of the policemen to her resistance. Also allude to Flinker’s entry on the growing travel restrictions for Jews.

Flinker, November 24, 1942 (continued)

“I then had to walk to school, which took about an hour and a half. [..] At that time I still thought that I would be able to return to school after the vacations; but I was wrong.”

Hannah Hershkowitz was born in 1935 in Biala Ravska, Poland. She survived the war. In her memoir, Hannah recalls:

“I was six years old. It was the first day of school in September, 1941. [..] Marisha, my best friend, invited me to come with her to school. We met in the morning and walked together with a lot of other children. We reached the big high gates. The watchman of the school was standing by the gate. [..] Marisha went through the gate, and I followed her, as the watchmen greeted her.

“Where are you going?” he asked me.

“To school, to the first grade,” I said proudly, and continued walking. The watchman blocked my way. “No, not you.”

“But I am six already – I really am!”

“You are a Jew,” he said, “Jews have no right to learn. No Jews in our school. Go home!” [..] Marisha, with the other children, ran into the building.

[..] I did not cry. I thought: I’m Jewish. There is no place for me. I stood there until no one stood in front of the school. Only me. The new school year had begun. But not for me.”

Dawid Sierakowiak, 15, Lodz, Poland:

November 29, 1939

“School is falling apart like an old slipper. Yesterday two men from the Gestapo came to the school at four o’clock.

November 30

“The school has been taken away. The students help the hired porters. They give us until tomorrow evening to clear everything out. A deadly feeling; mass looting of the library.”

Discussion Questions

- What was the meaning of the first day of school for you? Were you escorted?

- In light of these excerpts, how do you think the Jewish children felt being barred from school?

Dawid Sierakowiak, 15, Lodz, Poland:

October 3, 1939

“My father doesn’t have a job and simply suffocates at home. We have no money. It’s all shot! Disaster!”

Discussion Questions

- Try to describe how Dawid felt after his father became unemployed. How do you think this affected day-to-day life in his family?

To the teacher: A family naturally provides a certain degree of security to a child. Dawid seemed to know full well the immediate consequences of his father’s dire financial situation. No doubt having the traditional provider “simply suffocate” at home added great stress to an already stressful situation.

The Yellow Badge

Jews were forced to wear an identifying badge in order to identify them. This humiliating racial mark segregated them from society, and it made them easy targets for brutality. In the streets, Jews would often be harassed, beaten and humiliated in public.

Yitskhok Rudashevski, 14, Vilna:

July 8, 1941

“The decree was issued that the Vilna Jewish population must put on badges front and back - a yellow circle and inside it the letter J. It is daybreak. I am looking through the window and see before me the first Vilna Jews with badges. It was painful to see how people were staring at them. The large piece of yellow material on their shoulders seemed to be burning me and for a long time I could not put on the badge. I felt a hump, as though I had two frogs on me. I was ashamed of our helplessness. […] It hurt me that I saw absolutely no way out.”

Eva Heyman, 13, Nagyvarad, Hungary:

March 31, 1944

“Today an order was issued that from now on Jews have to wear a yellow star-shaped patch. The order tells exactly how big the star patch must be, and that it must be sewn on every outer garment, jacket or coat.

April 5, 1944

“[..] On my way to Grandma Lujza, I met some yellow-starred people. They were so gloomy, walking with their heads lowered. [..] I noticed Pista Vadas [a friend]. He didn’t see me, so I said hello to him. I know it isn’t proper for a girl to be the first one to greet a boy, but it doesn’t matter whether a yellow-starred girl is proper or not. Pa, Eva, he said, don’t be angry, but I didn’t even see you. The star patch is bigger than you, he said without laughing, just looking so gloomy.”

Discussion Questions

Yitskhok and Eva portray a sense of helplessness in the Jews who are forced to wear the badge.

- What do you think the badge meant to those who were forced to wear it?

Entry into the Ghettos and Hiding

The next stage of anti-Jewish persecution was closure into ghettos. Most of the Jews of Eastern Europe were forced out of their homes, leaving most of their belongings behind, and into ghettos - areas within cities and towns specifically allocated for Jewish residence. They were essentially held there as prisoners. Entire families would be packed together in extremely cramped, inhuman conditions.

Eva Heyman, 13, Nagyvarad, Hungary:

May 1, 1944

“In the morning Mariska [the family’s maid] burst into the house and said: ‘Have you seen the notices?’ No, we hadn’t, we are not allowed to go outside, except between nine and ten! [..] because we’re being taken to the ghetto. Mariska started packing [..] Mariska read in the notice that we are allowed to take along one change of underwear, the clothes on our bodies and the shoes on our feet [..]

Dear diary, from now on I’m imagining everything as if it really is a dream. [..] I know it isn’t a dream, but I can’t believe a thing. [..] Nobody says a word. Dear diary, I’ve never been so afraid”

Yitskhok Rudashevski, 14, Vilna, describes the expulsion to the new closed ghetto:

”It is the 6th of September (1941)

A beautiful, sunny day has risen. The streets are closed off by Lithuanians. [..] A ghetto is being created for Vilna Jews.

People are packing in the house. [..] I look at the house in disarray, at the bundles, at the perplexed, desperate people. I see things scattered which were dear to me, which I was accustomed to use. [..] The small number of Jews of our courtyard begin to drag the bundles to the gate. Gentiles are standing and taking part in our sorrow. [..] Suddenly everything around me begins to weep. Everything weeps. [..] The street streamed with Jews carrying bundles. The first great tragedy. [..] Before me a woman bends under her bundle. From the bundle a thin string of rice keeps pouring over the street. I walk burdened and irritated. [..] I think of nothing: not what I am losing, not what I have just lost, not what is in store for me. [..] I only feel that I am terribly weary, I feel that an insult, a hurt is burning inside me. Here is the ghetto gate. I feel that I have been robbed, my freedom is being robbed from me, my home and the familiar Vilna streets I love so much. I have been cut off from all that is dear and precious to me.“

Discussion Questions

- How does Eva try to cope with the new reality?

- What do you think Yitskhok meant when he wrote “the first great tragedy”?

Nazi anti-Jewish measures in occupied areas in Western Europe differed from those in the East. For various reasons, Jews were not closed in ghettos. However, the Nazis did enact similar anti-Jewish legislation: their citizenship was revoked, and they were banished from economic and social life. The decree for wearing the Jewish badge was also enacted in these countries.

Everyday Life in the Ghettos

The Jewish population in the areas under Nazi control lived in constant fear of abuse, looting and of deportation to the camps, which meant almost certain death.

Sixteen-year-old Moshe Flinker, who was living in Brussels at the time, writes:

January 7, 1943

“Last night my parents and I were sitting around the table. It was almost midnight. Suddenly we heard the bell: we all shuddered. We thought that the moment had come for us to be deported. The fear arose mostly because a couple of days ago the inhabitants of Brussels were forbidden to go out after nine o'clock. The reason for this is that on December 31 three German soldiers were killed. Had it not been for this curfew it could have been some man who was lost and was ringing at our door. My mother had already put her shoes on to go to the door, but my father said to wait until the ring once more. But the bell did not ring again. Thank heaven it all passed quietly. Only the fear remained, and all day long my parents have been very nervous.”

Eva Heyman, 13, Nagyvarad, Hungary, describes her situation behind walls:

May 10, 1944

“Dear diary, we’re here five days, but, word of honor, it seems like five years. I don’t even know where to begin writing, because so many awful things have happened since I last wrote you. [..] the fence was finished, and nobody can go out or come in. The Aryans who used to live in the area of the Ghetto all left during these few days to make place for the Jews. From today on, dear diary, we’re not in a ghetto but in a ghetto-camp, and on every house they’ve pasted a notice which tells exactly what we’re not allowed to do [..] Actually, everything is forbidden, but the most awful thing of all is that the punishment for everything is death. There is no difference between things; no standing in the corner, no spankings, no taking away food, no writing down the declension of irregular verbs one hundred times the way it used to be in school. Not at all: the lightest and heaviest punishment – death. It doesn’t actually say that this punishment also applies to children, but I think it does apply to us, too.”

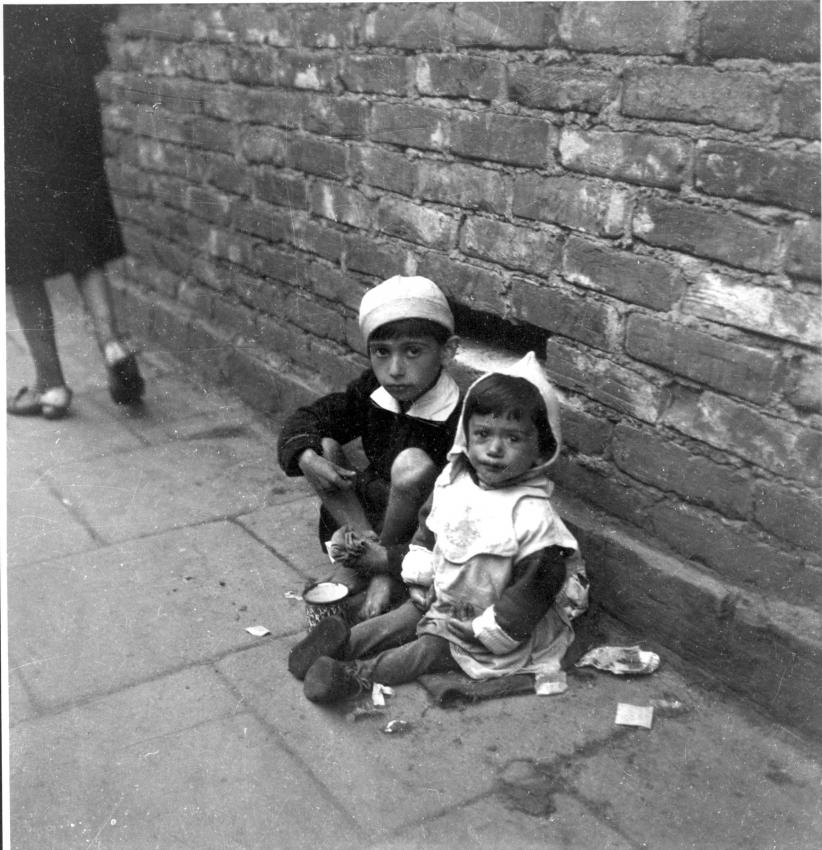

Food and medicine in the ghettos were strictly controlled by the Nazis. The food rations they allowed per person were inhuman; for example, in Poland, less than 10% of the minimum daily requirement. Many Jews died of disease, starvation and exhaustion, a condition that was grimly referred to as “Ghetto Disease”.

Dawid Sierakowiak, 17, Lodz, Poland:

May 24, 1941

“I’m damnably hungry because there isn’t even a trace left of the small loaf of bread that was supposed to feed me through Tuesday. I console myself that I’m not the only one in such a dire situation. When I receive my ration of bread, I can hardly control myself and sometimes suffer so much from exhaustion that I have to eat whatever food I have, and then my small loaf of bread disappears before the next ration is issued, and my torture grows. But what can I do? There’s no help. Our grave will apparently be here.”

The sight of the dead and the dying was a daily occurrence in many ghettos. This inevitably took its toll on the children.

Dawid Sierakowiak, 17, Lodz, Poland:

August 23, 1941

“I was staggered today when I hear about the death of our former neighbor in the building, Mr. Kamusiewicz. I think he is the first death in the ghetto that has left me so deeply depressed. This man, an absolute athlete before the war, died of hunger here. His iron body did not suffer from any disease; it just grew thinner and thinner every day, and finally he fell asleep, not to wake again.”

Life in the ghetto became a constant struggle for survival. The lack of goods quickly meant money had little real meaning. The impossible Nazi restrictions created a black market for all products necessary to live – food, medicine and energy sources to keep warm.

Yitskhok Rudashevski, Vilna:

“Father goes to work again in the munitions store houses. It is crowded and smoky in the house. Like many others I go hunting for firewood. We break doors, floors, and carry wood. One person tries to grab from the other, they quarrel over a piece of wood, the first effect of these conditions on the human being. People become petty, cruel to one another. […] I often go to work with father. I continue to go through the Vilna streets. The group goes to the munitions store houses […] In the evening I return with the group and fall back into the ghetto.”

Discussion Questions

- Eva, Dawid and Yitskhok describe different aspects of ghetto life. What picture arises from these excerpts?

To the teacher: Each of the children has a different observation on the new reality: Eva points out the disproportionate punishments that apply even towards children; Dawid talks of the hunger with great despair. His neighbor’s death affected him profoundly, and he fully expects to find his own death in the ghetto; Yitskhok notes how he’s forced to search for fuel, as his father works in the munitions store. He also points out the growing quarrelling and cruelty, brought on by the struggle for survival.

Hopes and Dreams

Despite the severe hardships Jewish children had to endure, many still harbored hopes and dreams for the future. These wishes were often expressed in the children’s diaries, drawings and poems.

Avraham Koplowicz was born in Lodz in 1930. He lived in Lodz during the war, and was eventually deported to the Auschwitz extermination camp and murdered. A notebook of his survived, containing drawings and poems.

A Dream

By Avraham Koplowicz

When I grow up and reach the age of 20,

I’ll set out to see the enchanting world.

I’ll take a seat in a bird with a motor;

I’ll rise and soar high into space.

I’ll fly, sail, hover

Over the lovely faraway world.

I’ll soar over rivers and oceans

Skyward shall I ascend and blossom,

A cloud my sister, the wind my brother.[…]

Discussion Questions

Many children expressed their hopes for the future during the war.

- Avraham wrote this poem while living in terrible conditions in the Lodz Ghetto. Yet this text presents a completely different reality – how do you think that can be? What is the role of imagination in survival?

Moshe Flinker, 16, Belgium:

December 8, 1942

”During the past few days when my mother raised the question of my future, my reaction was again one of laughter, but when I was alone, I too began to ponder this matter. What indeed is to become of me? It is obvious that the present situation will not last forever--perhaps another year or two--but what will happen then? One day I will have to earn my own living. [...] After much deliberation, I've decided to become...a statesman.”

Discussion Questions

- What can we learn from this excerpt about Moshe’s attitude towards the war?

- What influence, if any, do you think his situation had on Moshe’s decision to become a statesman?

On April 7, 1944, after being betrayed to the Gestapo, the entire Flinker family was arrested and eventually sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, where Moshe and his parents perished.

Eva Heyman, 13, Nagyvarad, Hungary:

May 30, 1944:

“[..] dear diary, I don’t want to die; I want to live even if it means that I’ll be the only person here allowed to stay. I would wait for the end of the war in some cellar, or on the roof, or in some secret cranny. [..] just as long as they didn’t kill me, only that they should let me live. [..] I can’t write anymore, dear diary, the tears run from my eyes, I’m hurrying over to Mariska… (End of diary)”

Éva was caught by the Nazis, along with her grandmother and grandfather, and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, where she was murdered. She was 13-years-old.