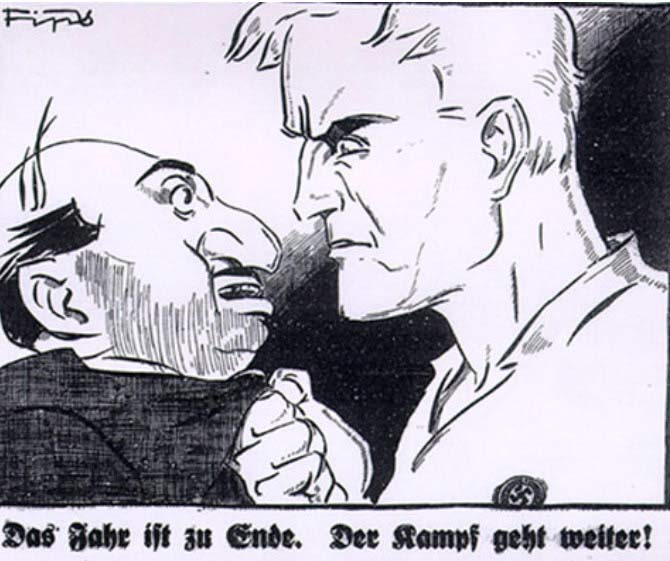

- The journal Kladderadatsch was a leading German satirical weekly that quickly adopted to National Socialism. It praised Adolf Hitler for his patriotic spirit after the failure of the 1923 Munich Putsch. In the early 1930s Kladderadatsch fully supported Hitler's policies and denounced the Social Democrats of trying to destroy Germany. Cartoons in the journal became increasingly anti-Jewish and expressed extreme right-wing views. The cartoon is partially reproduced in Eric Michaud, The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany. Trans. Janet Lloyd. Stanford University Press, 2004, illustration no. 2. where it appears without the caption underneath. It is correctly reproduced in Frederic Spotts, Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. Woodstock and New York: The Overlook Press, 2009, p. 97.

- Cit. Henry Grosshans, Hitler and the Artists. Holmes and Meier, 1983, p. 10.

- Correspondence between Wilhelm Furtwängler and Joseph Goebbels, April 1933. Source of English translation: Jeremy Noakes and Geoffrey Pridham, eds., Nazism, 1919-1945, Vol. 2: State, Economy and Society 1933-1939. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2000, pp. 213-15. Source of original German text: Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, April 11, 1933; reprinted in Paul Meier-Benneckenstein, ed., Dokumente der deutschen Politik, Volume 1: Die Nationalsozialistische Revolution 1933, edited by Axel Friedrichs. Berlin, 1935, pp. 255-58. Correspondence between Wilhelm Furtwängler and Joseph Goebbels about Art and the State (April 1933)

- Hitler’s Speech at the Opening of the House of German Art in Munich (July 18, 1937). This text (almost in its entirety) was reprinted in the Degenerate Art Exhibition Catalogue. English translation: Benjamin Sax and Dieter Kuntz eds. Inside Hitler’s Germany: A Documentary History of Life in the Third Reich. Lexington, MA and Toronto: D.C. Heath & Company, 1992, pp. 224-32.

- In chapter six of Mein Kampf (1924), Hitler reviewed the use of propaganda during World War I and commented on the function of propaganda in general. Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf, translated by Ralph Manheim. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1943.

- At the 1935 Party Assembly in Nuremberg (in which the Nuremberg laws were laid out), Hitler declared: “We must create the New Man so that our race will not succumb to the phenomenon of degeneration so typical of modern times.”

- Hitler’s Speech, Munich (July 18, 1937). Similarly, Hitler declared in his public address in Nuremberg in 1936 that: "Art is the only truly enduring investment of human labor." (cit. in Berthold Hinz, Art in the Third Reich. Pantheon, 1972. intro.)

- The Bauhaus was a school founded in 1919 by the architect Walter Gropius which sought to unify the decorative arts and crafts with the fine arts and technology with the idea of creating a 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in modernism; it encouraged experimentation and tended towards abstraction. As such, it came under attack when the Nazis came to power as cosmopolitan and tainted by foreign, Jewish influences. With its forced closure, many of its former staff and students emigrated.

- Adolf Ziegler was the foremost painter of the Third Reich and Hitler’s personal favorite. His painting The Four Elements hung in Hitler’s living room, and he was awarded the Gold Badge, the highest party member recognition, of the NSDAP. As President of the Reich Chamber of the Visual Arts, he was charged with organizing the Exhibition of Degenerate Art in Munich. He also expelled Expressionist artists such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and forebade him from any artistic activity "professional or amateur". See his letter to Schmitt-Rottluff in Addenda no. 2.

Grades: 9 - 12

Duration: 1 hour

This lesson provides an opportunity for students to examine how art and images were used as propaganda in Nazi Germany. Analyzing a cartoon published in Germany in 1933, students will explore a primary document which illustrates how the visual arts were forced into complete submission to censorship and National Socialist “coordination.” They will learn about the “aryanization” of art in Nazi Germany and look at examples of both the art the Nazis promoted in their exhibitions, parades and monumental sculpture as well as the “degenerate,” modern art they ridiculed and banned. Lastly, they will learn how to look at images critically – to interpret their implicit and explicit messages.

Didactic Objectives:

In this lesson, students will:

- analyze a political cartoon from Germany in the 1930s.

- define propaganda and learn to recognize some of its tactics and strategies of manipulation.

- discover how the Nazi regime used visual material as a powerful propagandistic tool in promoting their ideologies (advancing their platform of racial superiority) and furthering their political and social agenda.

- learn how to “read” and analyze images - for their efficacy, content and aesthetic value.

- debate important questions about the relationship between art and politics, state-sponsored censorship and free speech.

Step 1: Examine the cartoon. Pay close attention to the Note to Teacher.

Step 2: Read the handout “Historical Background: The Battle for Art in Nazi Germany.”

Step 3: Answer questions.

The Lesson

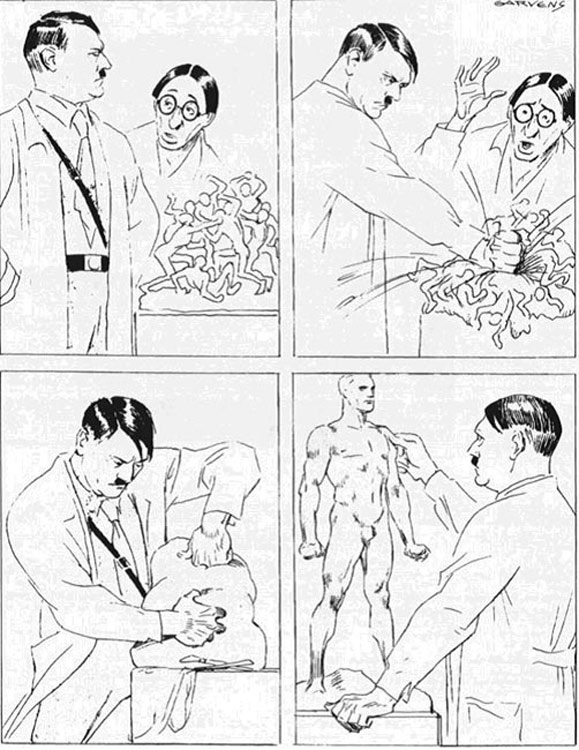

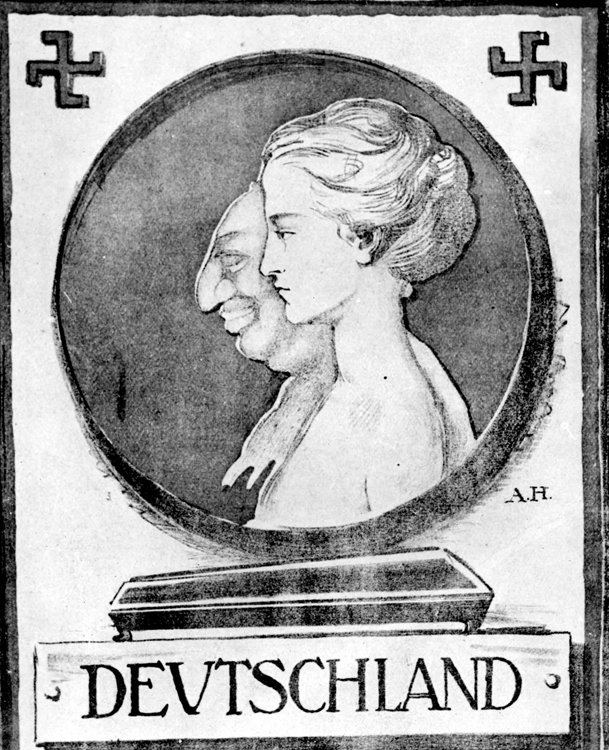

Look at the following image1 carefully. It is a cartoon composed of four frames with a caption beneath. Describe what is happening in each panel and then answer the questions that follow.

In 1933, the year Adolf Hitler assumed power, this cartoon was published in a satirical, right-wing German newspaper. The caption beneath it proclaims Hitler "Germany's Sculptor."

- 1. 1

Discussion Questions

- A story is being told with this cartoon. What is the storyline?

- There are two artists shown. How would you characterize each artist? What differences (in terms of clothing, facial expression, direction of the eyes, stance, pose, body language) do you see?

- How is the “modern artist” represented in the cartoon?

- What is a caricature? How is it used here and to what effect?

- How does the author of the cartoon use Antisemitic stereotypes? Why do you think he uses such stereotypes? Do you think his use of Antisemitic stereotypes is effective?

- How would you describe the differences between the two kinds of art/sculpture showcased?

- How is the cartoon laid out? Why does the artist organize these four frames in this order, with two panels over two panels? What does this composition accentuate? How does this layout create a study in contrasts which facilitates the viewer’s comparison of the two artists and their artistic visions?

- Hitler is one of the “artists” shown. In the caption beneath the cartoon, he is described as “Germany’s Sculptor.” What does the cartoon suggest is the role for art in Nazi Germany? What does it suggest is the relationship between art and power? What message is being communicated?

- The Nazis used many types of propaganda to disseminate their messages to the masses. What are some of the advantages of using visual images (such as this cartoon) as propaganda? How are visual images used as propaganda today?

- One way to describe what is going on in this cartoon is “censorship.” What can this cartoon tell us about Nazi attitudes towards freedom of expression? What does this image suggest about the role of the individual? About debate and dissension within National Socialism?

Research Topics

- The cartoon was made and published in 1933. Research other events which took place in 1933 at “Chronology of the Holocaust,” and “Nazi Germany and the Jews 1933-1939.” Report your findings about the context in which this cartoon was made to the class.

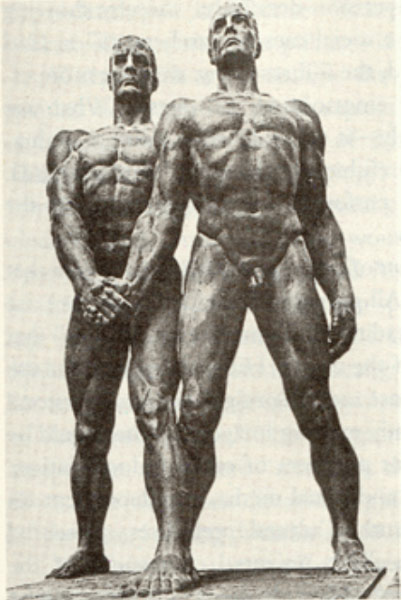

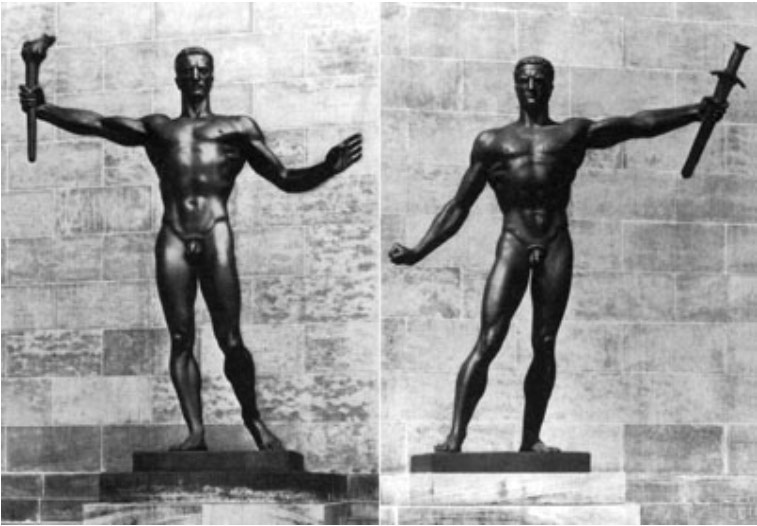

- The sculpture Hitler creates looks a lot like Greco-Roman classical statuary from antiquity. Why would this be important? Research Nazi art and present your findings to the class.

Note to the Teacher:

Created by O. Garvens in 1933, this cartoon strip in four frames shows an artist with stereotypically Jewish features (small and meek, with glasses and large nose) presenting a sculpture to Hitler in which a mass of small figures are shown chaotically intertwined. In the second frame, Hitler, dressed in a sculptor’s smock over his corporal’s uniform, delivers his verdict: he vehemently pounds on and crushes the artist’s sculpture with his closed fist, to the shock and surprise of the artist. By the third frame, Hitler has completely usurped the artist’s place. The “Jewish” modern artist is eliminated; his alternative “vision” or voice is silenced. The violence of the artist-Führer and the disappearance of the Jewish artist foretells the fate the Nazis had in store for the Jews and their art. It is now Hitler himself who reshapes the raw material left behind into one single, monumental figure of idealized muscularity and heroic proportions - effectively replacing the disparate, teeming, convoluted mass of the Jewish artist’s sculpture with one, unified, national body and one singular, national purpose (Ein Reich, ein Volk, ein Führer). In the final panel, Hitler surveys his own handiwork, literally looking up to his authoritarian creation. His colossus is the embodiment of the German nation. The sculpture Hitler creates in the cartoon exemplifies Nazi art: figurative, highly idealized works of monumental scale executed in traditional materials such as marble and oil painting derived from classical precedents, which were seen as uncontaminated by Jewish influences. (See Addendum no. 1 on Josef Thorak and Arno Breker for examples of Nazi sculpture.)

Nazi propaganda experts cast Hitler in many roles: as a military leader, politician, savior, and as a benevolent, nurturing father figure. This cartoon presents another persona Hitler himself cultivated: Hitler the artist and patron of the arts. Hitler promoted himself as both political and cultural leader of the German volk. He personally selected works to be included in the annual German Art Exhibitions. He delivered six speeches (which were printed as separate pamphlets) devoted entirely to the arts with titles such as “Art and Politics” and “German Art as the Proudest Justification of the German People.” He commissioned and supervised the building and operation of art museums. He had his own works declared “works of national importance.”2 Indeed, the National Socialist newspaper, Hakenkreuzbanner, declared in June 10, 1938: "Divine destiny has given the German people everything in the person of one man. Not only does he possess strong and ingenious statesmanship, not only is he ingenious as a soldier, not only is he the first worker and the first economist among his people but, and this is perhaps his greatest strength, he is an artist. He came from art, he devoted himself to art, especially the art of architecture, this powerful creator of great buildings. And now he has also become the Reich's builder."

Garvens’ cartoon presents Hitler as an artist-sculptor, literally molding a new nation, a new Aryan ideal. In April 1933, Goebbels would make the same analogy:

“Politics, too, is an art . . . and we who shape modern German policy feel ourselves in this to be artists who have been given the responsible task of forming, out of the raw material of the mass, the firm concrete structure of a people…. it is [the artists’] task to form, to give shape, to remove the diseased and create freedom for the healthy.3

The cartoon foregrounds the centrality of the arts in the Third Reich. It also anticipates the extreme measures which would be taken in the campaign against modern art, illustrating how the promotion of “Aryan” culture went hand in hand with the suppression of all other forms of artistic production. As Hitler announced at the opening of the House of German Art in the summer of 1937: “I declare here and now that . . . I am going to make a clean sweep of the artistic life in Germany.”4

For some ideas, see Addendum no. 1.

Historical Background: The Battle for Art in Nazi Germany

Propaganda is biased information designed to shape the opinions and behavior of mass audiences. Nazi propaganda is often associated with Hitler’s oratory and speeches or with well-known Nazi films such as Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (1934). However, propaganda can take many forms. Art, sculpture and visual mass media were employed by Nazi officials to sell ideas, control information, and shape public opinion.

Images carry enormous impact and are particularly effective tools of propaganda because they stand out from the printed page and attract attention; communicate information quickly; are memorable; appeal to our emotions; can be reproduced easily and circulated widely in mass media. Hitler understood the power and appeal of art as a kind of propagandistic “short-cut.” In Mein Kampf, he declared: “Propaganda is a truly terrible weapon in the hands of an expert… All propaganda must be popular and its intellectual level must be adjusted to the most limited intelligence among those it is addressed to.”5 Like the cartoon by Garvens, images can synthesize complex, highly abstract ideas and make them more specific and concrete.

- 5. 5

Cartoons-such as the one featured in this lesson-were an important vehicle for Nazi propaganda. Portraying the world as divided between pure and impure, the perfect and the degraded, they circulated symbols and stereotypes of difference. Garvens’ cartoon juxtaposes the impure, distorted Jewish body of the modern, “degenerate” artist with the pure, healthy Aryan physique of Hitler’s sculpture which exemplifies the Nazi concept of the “New Man.”6 Deployed extensively, Nazi visual propaganda played a key role in shaping the mindset which made the Holocaust possible: promoting national pride and solidarity but also playing on and fostering deep feelings of antisemitism.

- 6. 6

Nazi policy makers perceived art to be one of most important elements in building the Third Reich. High social value was placed on the visual arts in all their forms: they were promoted by the state and disseminated widely in leaflets and books, through postcards and stamps. They held a prominent place in public ceremony. As Hitler declared at the opening of the House of German Art in the summer of 1937: “we were the ones who created this state and have since then provided vast sums for the encouragement of art. We have given art great new tasks.”7 The aesthetic enterprise was at the heart of Nazi ideology, enlisted in the dream of creating a more beautiful, purified, hygienic world.

Control of the arts was central to Nazi totalitarian rule. In 1933, as soon as the Nazis came to power, Hitler established a ministry of propaganda under the direction of Joseph Goebbels. As Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Goebbels began the “synchronization” (Gleichschaltung) of culture, bringing all the arts in line with Nazi goals. Under his control, the Reich Chamber of Culture monitored all aspects of German culture - the press, education, music, film, theater and the visual arts. To ensure racial homogeneity and ideological conformity, membership was required of all professionals in the arts. No independent organizations were permitted.

- 7. 7

The National Socialists rejected and attacked just about everything that had existed on the art scene before 1933 (as a means of discrediting the culture of the Weimar Republic). Identified with internationalism and progressive politics, the Nazi regime criticized modern art as intellectual and elitist, foreign and Jewish, and symbolic of the forces which had humiliated Germany. Jewish, foreign and modern artists were labelled “degenerates.” Placed on black lists and branded enemies of the state, they were considered a threat to the health of the German nation. Systematic and institutionalized attacks on modern art were initiated. Within the first year, a large number of artists were banned from working (see Addendum no. 2); professors were dismissed from their posts in the Academy; art critics were censored or fired; museum directors and curators were replaced by Party members. The modern wing of the National Gallery in Berlin was shut down and the Bauhaus was closed.8 On May 10, 1933, members of the National Socialist German Students’ Association organized nationwide book burning ceremonies in which the works of “un-German” and Jewish writers were burnt. Artists suffered persecution, exile, incarceration and even death because of the content or style of their work, their political beliefs or religious affiliation.

- 8. 8

In the summer of 1937, Goebbels issued a decree giving Adolf Ziegler9 and a five man commission the authority to comb through German museums and public collections and confiscate any work they deemed “degenerate.” In all, the Aktion Entartete Kunst[5] confiscated over 16,000 works of art from over 32 German museums and public collections. Six hundred and fifty of these (by 112 artists) were earmarked for a special state-sponsored, “educational” exhibition entitled Entartete Kunst. Opening in the Hofgarten arcades of Munich’s Residenz on July 18, 1937, the exhibition traveled to eleven sites throughout Germany and Austria over a four year period and was seen by a record-breaking 3 million viewers. The goal of the blockbuster exhibition was to increase public revulsion for modern art and to enlist the public in the campaign to purify German culture from contaminating influences.

- 9. 9

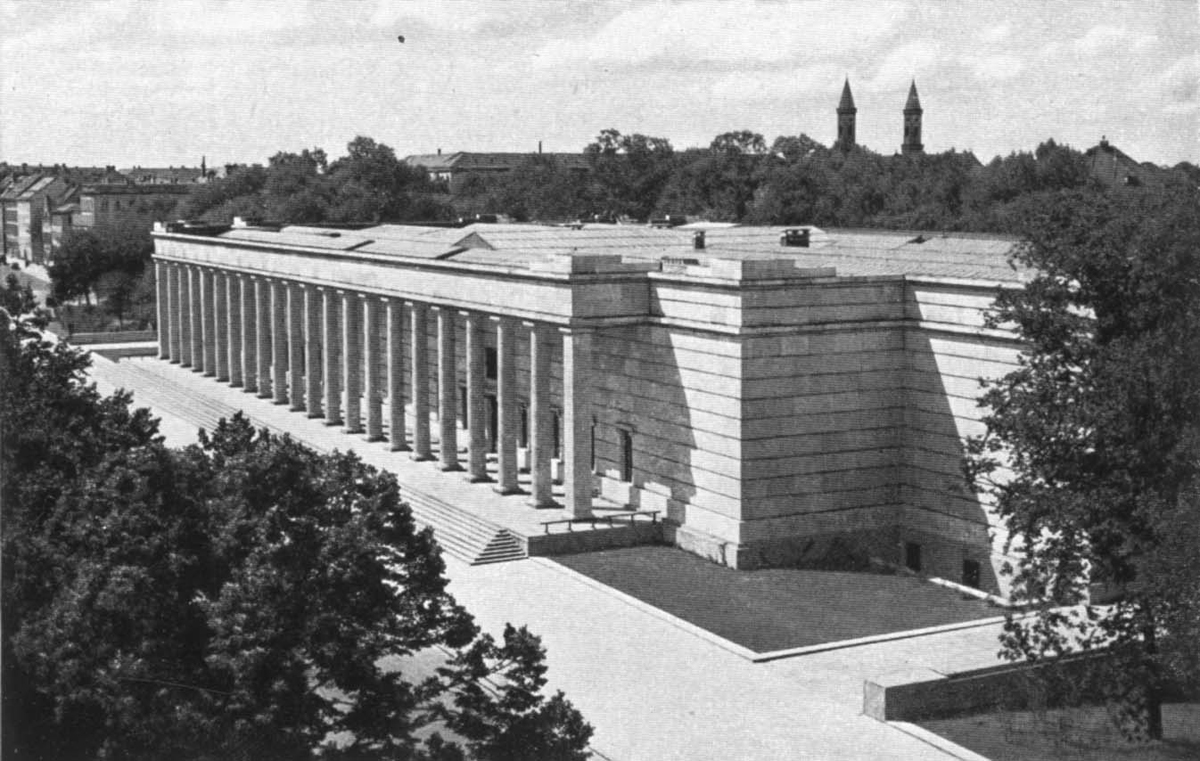

Strategically, the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung (The Great German Art Exhibition) opened the day before and across the street from the Degenerate Art Exhibition and functioned as its counter-image. Mounted in the recently completed Haus der deutschen Kunst (House of German Art), it was the first of eight annual exhibitions which showcased what the Third Reich regarded as Germany's finest art. A monumental, colonnaded, neo-classical building, the House of German Art was the first significant building commissioned by the new Nazi regime. At the ground breaking ceremony in October 1933, Hitler declared it a "temple [to] house a new German art.” For three days preceding the opening of the annual exhibition of the Great German Art Exhibition, Munich, draped in banners and flags, celebrated German Art Day with extravagant choreographed pageantry. The state spared no expense for these spectacular ceremonies. Consisting of monumental, gilded paper-mache heads of classical statuary, costumed Rhine maidens and warriors of the Teutoburg forest, the parade--which culminated in a finale of thousands of marching soldiers—proclaimed “Two Thousand Years of German Culture.”