During the Holocaust, every Jew in Europe was marked for death. Options for survival were few. Those who could hide had a better chance of staying alive, but who would have the courage to help?

Student Reflection Handout

Transcript Refuge in the Circus - Adolf Althoff

Hello and welcome to "The Human Spirit in the Holocaust", an Echoes & Reflections podcast, in which we shine a light on remarkable stories of courage, perseverance and hope during one of the darkest periods in human history. Echoes & Reflections is a partnership of the ADL, USC Shoah Foundation and Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Our podcast is produced by Yad Vashem.

I'm your host, Sheryl Ochayon.

What do you think of when you think of the circus? Trapeze artists flying through the air, performers in dazzling costumes, clowns who make the audience roar with laughter, the ringmaster in his red jacket and black top hat! Once upon a time there were also animal acts where lions jumped through hoops of fire, and huge elephants balanced on tiny balls. For centuries, the music, colors and thrills of the circus have brought excitement and wonder to millions of people around the world.

This is the amazing story of not one, but two circuses and their families. When the Nazis threatened one of these families, the other undertook a daring rescue mission to save them, more dangerous than any stunt performed on the high wire!

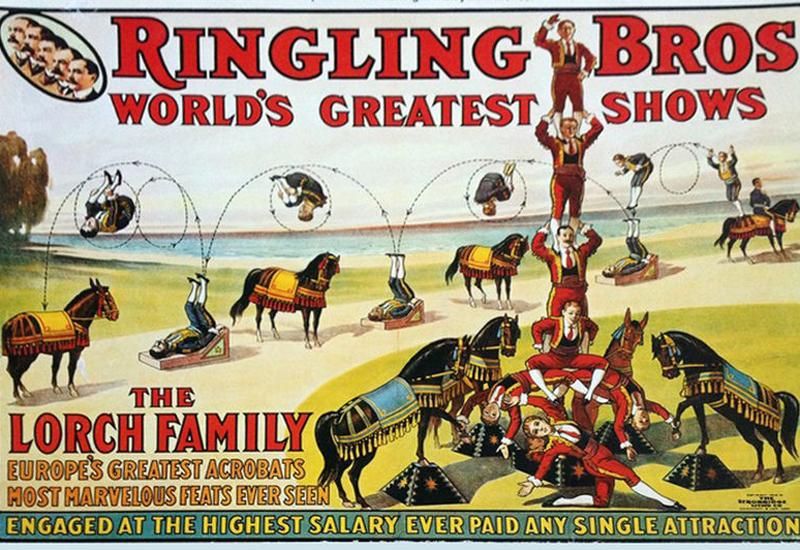

The first was called the Lorch circus. It was known for its amazing artistic horsemanship and acrobatic stunts. People came to see one performer juggling another with his feet – a feat that required incredible strength and agility. Based near Darmstadt, in Germany, the circus had real star power.

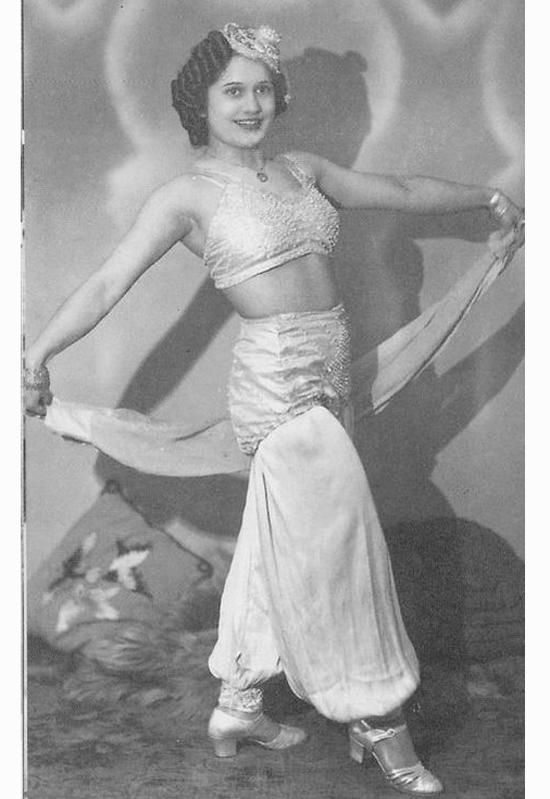

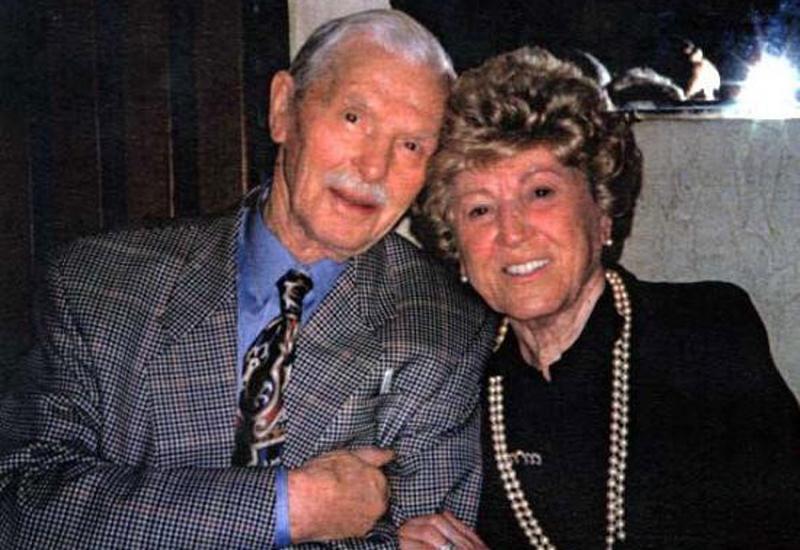

Irene Danner was born into this exciting circus life – her grandfather, Julius, was an acrobat who could spin other flyers into consecutive somersaults in the air with his feet. In fact, he had toured Europe, the United States and South America, even performing at Madison Square Garden in New York City! He taught Irene acrobatics when she was a little girl. She became fascinated by circus life.

[Irene Danner]

" I wanted to become a circus artist since I was 6 years old. After school I quickly did my homework, then ran outside to our backyard and turned cartwheels and handstands, probably a hundred back flips quick as lightning."

Irene’s parents were the circus performers Hans and Alice Danner. In those days, circuses traveled across Europe, setting up their tents in towns and villages. So while her parents and grandfather were on the road working with the circus, Irene and her younger sister, Gerda, were raised by their grandmother, Sessy. Sessy would tell them stories while Irene sat on a low stool near a cozy hearth with her head on her grandma’s lap. When Julius returned from touring, he taught the girls Jewish traditions, like observing the Sabbath, the Jewish day of rest. The girls upheld these traditions, even though they were only half-Jewish.

The rise of the Nazi party in Germany in the early 1930’s cast a dark and frightening shadow over Germany. Nazism promoted racist antisemitism. The Nazis blamed the Jews for Germany's defeat in WWI, and for its economic and other problems. Anti-Jewish propaganda increased. Jewish businesses had a harder and harder time, as clients began to stay away. In 1930 the Lorch Circus lost many performers and much of its audience. It was forced into bankruptcy. Irene's parents had to find work elsewhere.

Once Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party came to power in 1933, more and more anti-Jewish policies were implemented. Jews were removed from their places of work, their businesses were taken away and their German citizenship was revoked.

At this time, Irene was a top student at the local elementary school. She remembers how she felt when the Nazis came to power.

[Irene]

"There was no change at the beginning. I was only sad because they wouldn't let me join the youth movement. But then they began with the inflammatory songs, such as 'Germany awaken, Judah perish.' As they were singing 'Judah perish' the kids would point their fingers at me. The teacher Hubert was the worst. He incited my schoolmates against me. Then I was excluded from physical education. All of a sudden my friends didn't want to play with me any longer…

At school the children ridiculed me – 'stinking kike.' At home I took off all my clothes and washed them. I soaped my body, brushed my teeth, continuously chewed mint, but to no avail. I was a stinker and I was ashamed to be such a 'kike.'"

Her classmates' insults scared Irene. In the summer of 1936 when Irene was only 13 years old, her grandmother pulled her out of school due to the growing antisemitism.

[Irene]

"One day the forester of the town knocked at our door. He barked at us: 'Jews are not allowed to have dogs.' He grabbed our two pets who were standing next to my grandmother, wagging their tails and took them away. He shot them…"

At the time, Irene’s parents were working for the Caroli family, an Italian horse-riding troupe. They trained Irene, and she learned to jump from one horse to another as they galloped, flying through the air. She became a great sensation. Irene stayed on until an official order came that forbade the Carolis to employ her. She was fired.

[Francesco Caroli]

"[She] was like a sister to us. She belonged to us. Irene was a really good person who took her work very seriously and put her heart into it. …Suddenly not only was she forbidden to work but she was forbidden from entering the circus at all. And, of course, we all complained but we also saw that nothing could be done against the order. It was of course very sad and she wasn't allowed to be with us anymore. For everyone it was like a farewell."

That's how Francesco Caroli remembered it.

The November pogrom, also known as Kristallnacht, in 1938 reached the area of Darmstadt. The local synagogue was looted. The prayer leader was thrown violently off the roof. He and 18 members of the congregation were sent away. When WWII began in 1939, Germany's policies against the Jews became more extreme and finally, murderous.

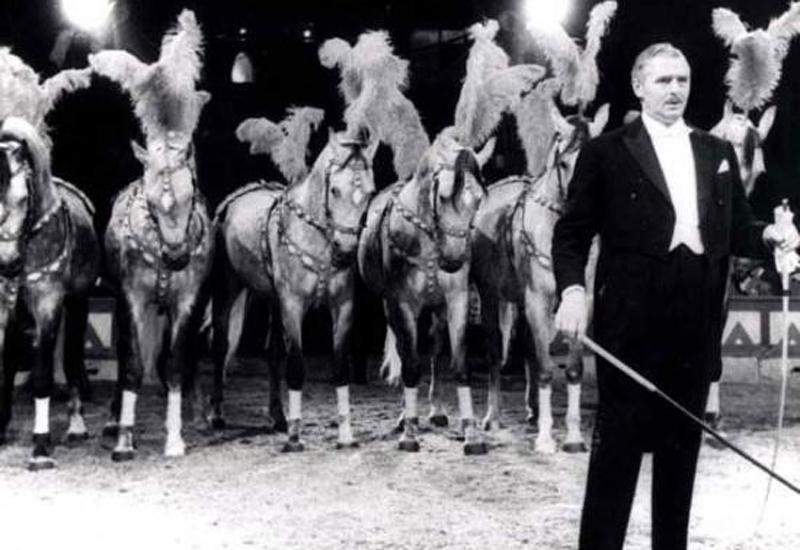

It sounds strange now, but even during the war years there were still circuses touring all over Europe, which is how we meet the second circus in our story. It was called the Adolf Althoff Circus, and it dated back to the 18th century, Germany’s oldest circus dynasty. It was a big one, with 90 artists and their families. In 1941 they set up their wagons, of all places, near Irene's home in Darmstadt.

You would think Irene would have run to see the circus – she loved it so much. But she was so frightened and nervous due to the changing atmosphere and rising antisemitism, that her grandmother, Sessy, had to convince her to go. Finally she went. Petite and beautiful, she caught the eye of a performer named Peter Bento, who was one of a family of musical clowns from Belgium. He walked her home that night. She couldn’t believe she had found someone who could be a friend.

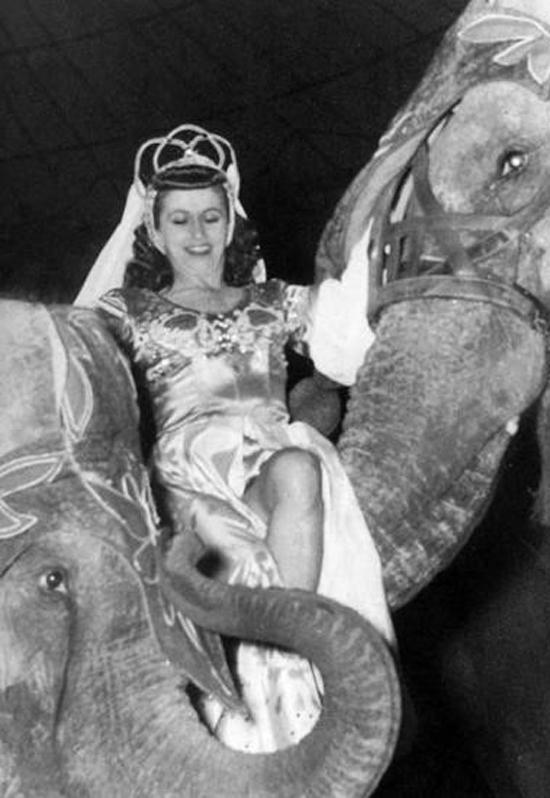

By that time, Irene was 19. As a Jew in Nazi Germany she was forbidden to work. The German Ministry of Culture had imposed severe restrictions on employing Jews. But Irene was desperate – she decided to take a chance. She asked Adolf Althoff, the director of the circus, to take her on as a performer. He knew she was Jewish and he knew that employing her was dangerous. In spite of this, he agreed to engage her in his circus under an assumed name. He made her part of an elephant act, together with Adolf's wife and another young woman. The women, in their sequined costumes, were boosted up in the air on the elephants’ curling trunks and hoisted onto their broad, gray backs. Irene and Peter fell in love, but they were forbidden to marry by German racial laws.

As persecution of the Jews reached a terrifying climax, Irene's family was torn apart. Her grandfather Julius, who was invited to perform in Belgium, was trapped there when the German army invaded; his family never saw him again. In Darmstadt, the Jews were forcibly taken from their homes and deported to concentration and death camps. In March 1943, Irene's beloved grandmother, Sessy, was taken. Irene was heartbroken; her grandma was everything to her. Sessy was murdered at Auschwitz.

Their neighbors watched what was happening to the well-respected Lorch family and other Jewish people they had known for generations. They shrugged their shoulders. What could they do about it?

There was one man who felt differently. Adolf Althoff remembers:

[Adolf Althoff]

"I knew what danger these people were in. What was I to do? I couldn't deliver them to the Nazis. If I did, it was 100% certain that they would be taken away."

By this time, every Jew in Germany was in mortal danger. And every non-Jew who helped them was in danger as well.

Irene's Jewish mother, Alice, and her younger sister, Gerda, were desperate to find shelter. Irene’s father Hans needed to hide as well, even though he was not Jewish, because he had refused to divorce Alice, who was. Irene turned once again to Adolf Althoff to provide a safe shelter at his circus – this time for her entire family.

Years later, Adolf recalled:

[Adolf Althoff]

"And then she [Irene] asked me whether her mother and her sister could also join. And she told me the reason …. I had to help them. I couldn't leave them to the Nazis. To be honest, I have no idea how I could have done this. But I was glad to have done it."

For almost three years, until the end of the war, Althoff let all four Danners - Irene, Gerda, Alice and Hans - work in the circus. He got them forged papers using Italian names. It was dangerous to harbor Jews. Traveling from place to place made things somewhat easier, but at every new stop on their tours, the circus was searched by the Nazis.

Althoff was a very brave, principled man who refused to join the Nazi party. He was helped by his wife Maria, who played a big part in hiding and looking after the Danners, and by Mohammed Saharaoui, a Muslim acrobat from Morocco who was Peter's best friend. They were able to warn the family when a search was underway with the cue “Go Fishing,” signaling them to run and hide. Adolf would then distract the Nazi officials.

[Adolf Althoff]

"When the Nazi gentlemen came to check on us, I usually knew about it in advance… I was especially kind, gave them free tickets for the extended family, generously poured cognac, told them stories from my past – for example how I used to perform in Kiev with the bears… When they wanted to check the premises, I usually was able to divert them. I told them that I had a meeting with one of their superiors, but that my wife Maria would take care of them. By that time she had set the table in our wagon, and offered them coffee. She never forgot the bottle of cognac. Our hospitality became famous."

The Althoffs were in danger every minute of every day that the Danners stayed with them. Yet, as Althoff explained after the war:

[Adolf Althoff]

"There was no question in our minds that we would let them stay. I couldn't simply permit them to fall into the hands of the murderers. That would have made me a murderer."

The Althoffs’ choice to do something when everyone else felt they could do nothing enabled the Danners to survive the Holocaust. Irene and Peter had two children during the war and three more after it.

In appreciation of their remarkable courage in standing up against the Nazis and saving the Danners' lives, the State of Israel recognized Adolf and Maria Althoff as Righteous Among the Nations. This title is awarded to non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust by actively trying to save Jews from the threat of death, and did so without seeking any payment or other reward. During the very dark time of the Holocaust, when compassion was rare and most people looked away indifferently, the Righteous were the few who cared and took action.

In his speech when receiving this honor in 1995, Adolf Althoff said,

[Adolf Althoff]

"We circus people see no difference between races or religions."

***

Thanks for listening. For more podcasts about the human spirit in the Holocaust, please see the Echoes & Reflections website, at EchoesandReflections.org. Our thanks to Birte Hewera, as the voice of Irene Danner, to Moshe Cohen, as the voice of Adolf Althoff, and to Rocco Giansante, as the voice of Francesco Caroli. Special thanks to Sarah Levy and to Stav Meishar for her expertise.