When the Germans condemned the Jews to live in ghettos, they cut them off from the world. To have any chance of surviving, it was vital to resist in any way possible. To have any chance of fighting back, it was crucial to smuggle in secret information and weapons.

Listen to Vladka's story on Spotify | Apple | Google

Transcript One Fierce Female - Vladka Meed

Hello and welcome to "The Human Spirit in the Holocaust", an Echoes & Reflections podcast, in which we shine a light on remarkable stories of courage, perseverance and hope during one of the darkest periods in human history. Echoes & Reflections is a partnership of the ADL, USC Shoah Foundation and Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Our podcast is produced by Yad Vashem.

I'm your host, Sheryl Ochayon.

Imagine this. It is spring 1943 in Warsaw. The scent of flowers is in the air. Local Polish people are strolling under a brilliant blue sky, an Easter fair with a carousel that plays music is being assembled in the center of the city. But World War II is raging in Europe, and not far away in the Warsaw ghetto, cut off by high brick walls, the atmosphere is tense. A few hundred young Jews, most in their teens and twenties, have decided to fight against the German army, the most powerful army in the world. They have never held guns in their lives and have almost no weapons or ammunition, but this doesn't stop them – together they have created the Jewish Fighting Organization. They have been pleading with the world for rifles, explosives - anything to help them fight. These

young people, together with a parallel fighting force called the Jewish Military Union, are about to launch the first, largest and most famous civilian uprising in the history of WWII against the German army. This uprising will be known as the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising – an unequal fight that shattered the limits of the imagination.

It is dawn. A young woman sneaks into an alley near the ghetto wall known to be a smuggling area, where the police and factory foreman can be bribed. Barely out of her teens, she is dressed like a shopkeeper to evade suspicion. She approaches the ladder that has been propped up against the wall for the smugglers. She is carrying a parcel that looks like a package of food. But it is actually something else.

[VLADKA]:

"These were packages of 5 kilo dynamite put in in greasy paper to look like I am smuggling butter. Usually the smugglers paid a certain amount of money [to] the foreman and he was staying near the ladder and they gave him the money, went up the ladder on the other side and jumped on the other side of the wall into the ghetto. And the smuggle was going on and it was [me] next and I gave also the money [to] the foreman and I went up with [my] package. It was not suspicious for them. And while I was on top of the wall, shooting started. And I was on top and shooting started to come closer. The foreman snatched away the ladder and I was not able, not to go back to the Polish side and I didn't see anybody on the Jewish side. And I was afraid to jump, not knowing too much about dynamite, that maybe this can explode. So, I was on top and the shooting came closer and I was sure that I am done. But suddenly the two people who were waiting for me saw me there on top, and they made a human ladder from the ghetto side and brought me down, and we ran away just in time."

This sounds like a scene from an action movie. But it's a true story. The name of our heroine is Vladka Meed.

Vladka was born Feigele Peltel in Warsaw on Dec. 29, 1921, the oldest of three children. Her family was lower middle class, close-knit and traditional - they observed the Sabbath and Jewish customs but were not very religious.

When she was 17 years old, the Germans invaded Poland. Vladka, who had fair hair and blue eyes, and spoke fluent Polish, quickly realized that this worked to her advantage. Jews in Poland were subjected to humiliation and abuse in the streets by the brutal German occupiers. Vladka's father was beaten up for being Jewish. But Vladka could convincingly pretend to be Polish. She went to rich neighborhoods of Warsaw to trade household items for food. In December 1939 when the Jews were forced to wear armbands with a Jewish star, she dared to take hers off.

Warsaw was then home to the largest Jewish population in Europe, with over 375,000 Jews. In the fall of 1940 the Germans created a walled ghetto, imprisoning them. Though they constituted 10% of the population, the Jews were confined to 2.4% of the city's area. This resulted in horrific overcrowding especially since tens of thousands more Jews were brought in from neighboring areas. At its peak, some 440,000 people were forced to live, isolated, behind the ghetto walls, seven to each room on average. Disease quickly spread. Food and heat were limited by the Germans. The Warsaw ghetto, like others of the over one thousand ghettos created during the Holocaust,

became a death trap. Jewish life became desperate. Vladka's father contracted pneumonia and died, aged 47.

Vladka had been involved in youth movements even before the war, but now they took on greater significance. After Jewish schools were closed by the Germans, young people defiantly continued their education, gathering secretly to listen to lectures, read literature, and hold seminars. They created "children's corners" and gave lectures to the adults. Vladka, too, participated in this cultural resistance.

[VLADKA]:

"But I still remember the atmosphere, the uplift, that in the ghetto with so much

starvation, and the typhoid epidemic which started and the hunger and misery,

we were talking about literature. And a young girl was talking to older people

and they were listening, and somehow it was, they thought, the hope that this

will pass, it is a time that will not remain forever. And this kind of hope was

constantly in the life of the ghetto."

Vladka drew inspiration from her mother, who sacrificed much to enable her family to survive. She ate less so her children could have more, and sold household items for food. It was important to her that her son, Chaim, had a Bar Mitzvah, a Jewish rite of passage for 13-year old boys where they read a portion from the Torah. With no money to pay for a teacher, she traded part of her bread to pay him, though she herself was starving. She was a model of resistance.

Vladka greatly admired the inner strength of her mother and women like her, whose subtle yet persistent determination enabled them to resist the Germans in their own quiet way.

In the fall of 1941, rumors reached Warsaw of Jews further east being murdered by the Germans en masse. At first, no one understood that the entire Jewish population of towns and villages was being deported to their deaths. They didn't believe this could occur in Warsaw – after all, it was the capital of Poland and a thriving metropolis. But in the summer of 1942 when they witnessed how almost 300,000 Jews were forced into cattle cars, the rumors were proven true. They later learned that these Jews had been taken to the Treblinka death camp, never to be seen again.

Youth movements decided to fight.

Vladka's mother, sister and little brother were swept away in this tidal wave. Vladka was devastated. Having lost her entire family, she channeled her depression into fighting the Nazis. This gave her life meaning. She already knew how to exploit her looks and fluent Polish; now she did this in the service of the underground youth movements that coalesced into a fighting force.

Vladka was one of a small group of women called "couriers". These were incredibly brave young women, some still in their teens, who often looked Christian and so could move around freely without arousing suspicion. They risked their lives to travel from place to place; they snuck in and out of ghettos. They smuggled guns, ammunition,

explosives, money and information. Were it not for these strong women, armed

resistance in the ghettos would not have been possible. The women relied on their looks and their instincts to cope with danger. They camouflaged their Jewishness better than men, who could be identified because they were circumcised.

Vladka smuggled arms and dynamite into the Warsaw ghetto. She also smuggled precious things out of the ghetto, including Jewish children to be hidden outside the ghetto by non-Jews. One mission was particularly risky. Vladka mixed with hundreds of Jewish workers who were leaving the ghetto for forced labor outside it. A group leader,

Named Ben, allowed her to join his battalion, but Vladka was stopped by a German guard. Ben later remembered:

[Ben]:

"Usually it's much easier for me to take out men than women. Because the slave workers mostly were men. I walked over with her to the gate of the ghetto. She was in the middle of our group. We passed the gate and from all the people, he picked out her for a search. Would I have known what she was carrying I would probably never take her because I would have been responsible for this. Because she was carrying the map of Treblinka - a prepared map with the gas chambers, with all these things, that supposedly came to London, and I was very scared. She didn't tell me what she has. She went through with us and she immediately disappeared as we are starting to march."

It was a close call – Vladka had hidden the map in her shoe. When the guard ordered her to remove her clothes, and her shoes, Vladka was sure she was about to die, but she was saved miraculously by a distraction. Ben later became her husband.

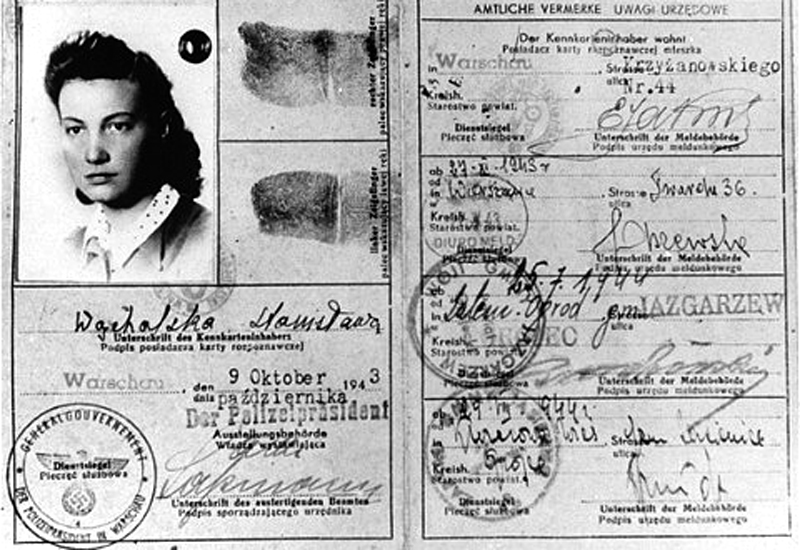

In her role as courier, Vladka lived outside the ghetto, using a false name and ID, pretending to be a good Polish Christian girl, smiling and keeping a poker face while her heart bled for the Jews of the ghetto.

On April 19, 1943, a large force of German soldiers with machine guns, tanks and armored carriers surrounded the Warsaw ghetto. Several hundred Jews with primitive homemade bombs, a few smuggled guns and no military training fought back.

The fight was completely uneven, but in an astounding display of strength and courage, the starved and oppressed Jewish fighters of the Warsaw ghetto succeeded in holding off over 2,000 German soldiers for an entire month. The Germans finally suppressed the uprising by burning the buildings of the ghetto one by one.

From outside the ghetto, Vladka watched black smoke rise and heard the gunfire.

[VLADKA]:

"And I saw how the ghetto was in flames, how the Jewish houses were burning and people were jumping from balconies. And I remember staying at the window and seeing the flames, and Mrs. Dubiel constantly telling me 'Get away from the window, they will see you, they will see you.' But how could I get away when the world which I was born and connected get up in flame?"

Vladka survived the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and carried out more missions for the Jewish underground to rescue Jews from labor camps. She also fought together with the Poles against the Germans in the Warsaw Uprising of 1944.

Vladka always believed that the resistance and courage of the fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising arose from the culture of preservation of human values that existed in this and other ghettos. This included the quiet acts of the mothers, the illegal educational activity, soup kitchens, theaters and orchestras, and many more acts that sustained the

Jews' sense of self despite the Germans' dehumanizing treatment. There could have been no armed uprising without this.

[VLADKA]:

"The armed resistance was possible because it was an ethical, moral resistance going on in the ghetto before deportation. It is a chain. It didn't come suddenly. The young people came from the houses of the parents who were transported to the gas chambers, but the houses were full of beliefs, of hope, of belief in humanity, of justice. And this was a chain leading to active resistance. And this is why I cannot separate the Uprising or active resistance or the partisan resistance from the resistance which took place in the quiet so-called times in the ghetto. This was the base, the foundation. And the foundation goes even before the war, the outbreak of the war. "

Vladka's story is a story of incredible bravery and courage. She left us with a message:

[VLADKA]:

"I would like also to say to people not to take for granted – not freedom, not justice. You have to stand up for it. You have to defend this. To be your brother's keeper. To remember that the other needs, too, your help. Not to be passive when things are going on around you. Not to be indifferent. To be a participant in life, and to defend the rights of humanity."

***

Thank you for listening. For more podcasts on the Human Spirit in the Holocaust, please visit the Echoes & Reflections website, at echoesandreflections.org. To learn more about the stories of Vladka and Ben Meed, you can find their complete testimonies on the USC Shoah Foundation website. Special thanks to Sarah Levy.

.jpg)