For Middle School Pupils

The following is a unit on Janusz Korzcak and his Deputy in the Warsaw Orphanage and right hand, Stefania Wilczynska (Stefa).

The unit comprises four parts:

The first two are short biographical depictions of Korzcak and Stefa's lives.

The third part presents central values in Korzcak's educational ideas and the way he and Stefa implemented them in the lives of their young wards.

The final part is a suggested lesson plan for teachers using two poems about Korzcak, presented together with a monument dedicated to him and located on the site of Yad Vashem.

"My life has been difficult but interesting. In my younger days I asked God for precisely that."1

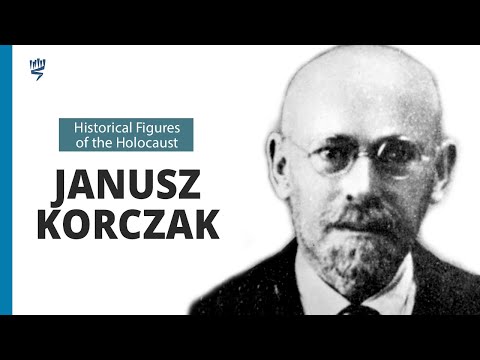

Janusz Korczak was born Henryk Goldszmit on July 22nd, 1878 to an assimilated Jewish family in Warsaw, Poland. He was an author, a pediatrician and a pedagogue.

When Korczak's father, a prominent lawyer and the sole source of income of the household, died after illness in 1896, the family was left without a source of income and Korczak became the sole breadwinner for his mother, sister, and grandmother. The family environment in which he grew up undoubtedly influenced his personal development and his awareness and sensitivity toward social problems.

In 1898 in a literary contest, he used for the first time the pseudonym Janusz Korczak, a name he took from the book Janasz Korczak and the Pretty Sword Sweeper Lady written by the Polish writer Józef Ignacy Kraszewski.

Between 1898–1904 Korczak studied medicine at the University of Warsaw and also wrote for several Polish newspapers. He specialized as a pediatrician and worked at the Children’s Hospital.

In 1905-1906 he served as a military doctor in the Russo-Japanese War. During the war he came to the conclusion that it was as an educator rather than as a doctor that he could really make a lasting impression and contribution to the world.

In 1908 Korczak joined the Orphans Aid Society. There, in 1910, he met Stefania Wilczyńska (Stefa), who would become his closest associate.

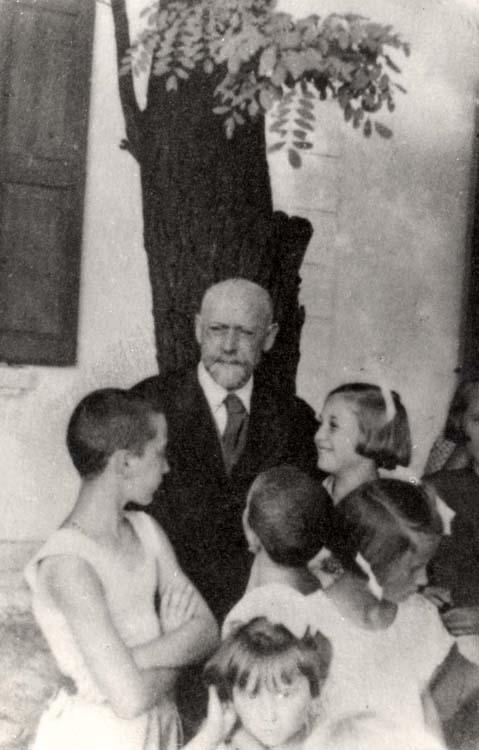

In 1911–1912 he became the director of Dom Sierot, the orphanage of his own design for Jewish children in Warsaw. He appointed Stefa to work with him as his Deputy Director and house mother. About one hundred children lived in the orphanage. He established a 'republic for children' with its own small parliament, law-court and newspaper and reduced his other duties as a doctor.

During World War I Korczak served as a military doctor in the Russian Army. And then during the Polish-Soviet War in 1919-1920 he served again as a military doctor, this time with the rank of major.

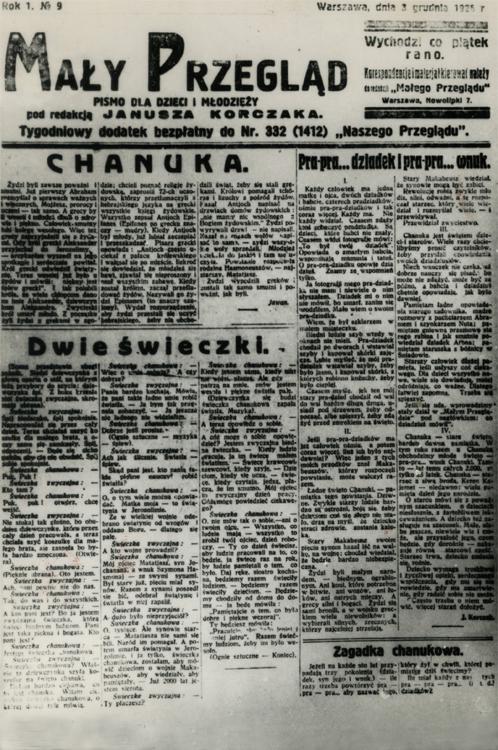

In 1926 Korczak started a newspaper for Jewish children, the Mały Przegląd (The Small Review) which was written in Polish. At the same time some of his books for children such as “King Matt the First” or “How to Love a Child” for adults, gained him literary recognition and a wide popularity and readership.

During the 1930s he had his own radio program which was widely broadcasted throughout Poland until it was closed down due to growing antisemitism in Poland.

In 1934 and in 1936 Korczak traveled to Palestine under the British Mandate, stayed in kibbutz Ein Harod and observed the educational system in the kibbutz. When the situation worsened in Poland, Korczak decided to immigrate to Palestine, and in 1939 met with Yitzhak Gruenbaum, a member of the Jewish Agency, to consult with him about plans for immigration.

In 1939, when World War II erupted, Korczak was going to volunteer for duty in the Polish Army but due to his age he stayed with the children in Warsaw. At the end of November 1939, the German authorities forced every Jew to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David. Korczak refused to wear the armband or remove his Polish officer uniform even though he was putting himself in danger by not doing so.

When the Germans created the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, his orphanage was forced to move to the ghetto. Korczak went with the children even though he had repeatedly been offered shelter on the “Aryan side”. He always refused these offers saying that he could not abandon his children. During the ghetto period, Korczak and Stefa's highest concern was the children's food. Korczak went from door to door and begged for food, warm clothes and medicines for the children. Despite his frail health and personal problems he coped with the reality of the ghetto and did everything to better the life of the children in the orphanage. In the ghetto, Korczak wrote a diary with notes, memories and observations; in it he portrayed his inner world and personal view on life in the ghetto. This diary was published in Poland in 1958.

On the 5th of August 1942, he boarded the train with the children to Treblinka where together with Stefa, about 12 members of his orphanage's staff and around 200 children, all went to their deaths in the gas chambers.

Janusz Korczak's work with children allowed him to put in practice his educational views, but it was as a writer that Korczak had the greatest effect during his lifetime and in generations to come. He wished, and succeeded, to reach both adults and children and to make a deep and lasting impression on them. He wrote over twenty books, many of them about children's rights and child's life experience in the adult world. Among his most influential works we find: "How to Love the Child" (1921), "King Matt the Reformer" (1928), "The Child's Right to Respect" (1929) and, "Rules for Living" (1930).

In the Ghetto

In 1939, when World War II erupted, Korczak was going to volunteer for duty in the Polish Army but due to his age he stayed with the children in Warsaw. During the first months of the occupation, the number of children in the orphanage increased because it was necessary to receive children who lost their families during the bombing. At the beginning of 1940 there were about 150 children in the orphanage. At the end of November 1939, the German authorities forced every Jew to wear a white armband with a blue Star of David. Korczak refused to wear the armband or remove his Polish officer uniform even though he had been imprisoned for some time.

When the Germans created the Warsaw Ghetto in 1940, his orphanage was forced to move to the ghetto. Korczak went with the children even though he had repeatedly been offered shelter on the “Aryan side”. He always refused these offers saying that he could not abandon his children. During the ghetto period, Korczak and Stefa's highest concern was the children's food. Korczak went from door to door and begged for food, warm clothes and medicines for the children. Despite his frail health and personal problems he coped with the reality of the ghetto and did everything to better the life of the children in the orphanage.

With all the difficulty and background of changing orders, Korczak stuck to his educational path. The orphanage continued to operate according to the arrangements that characterized it in the pre-war period, and the children continued to take part in the administration of the institution and in conducting public trials. At the orphanage there were plays and concerts that attracted the public and every Saturday after the educator's meeting at the orphanage, Korczak would tell a story to the children they had chosen for themselves. In addition, in view of the harsh reality and sometimes the loss of values outside, Korczak tried his best to educate the children to honesty and truth. In the ghetto, Korczak wrote a diary with notes, memories and observations; in it he portrayed his inner world and personal view on life in the ghetto. This diary was published in Poland in 1958.

On the 5th of August 1942, he boarded the train with the children to Treblinka where together with Stefa, about 12 members of his orphanage's staff and around 200 children, all went to their deaths in the gas chambers.

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

It is important to emphasize that even after transferring to the ghetto, against the background of multiple hardships -hunger, cold, uncertainty for the future- Korczak still engages his energies to continue with his educational endeavors, his beliefs in equality and respect for the child in directing the orphanage. Discuss this with the pupils.

Stefania was born in Warsaw in an assimilated bourgeoisie home in 1886. She took a course to become a kindergarten teacher and studied natural sciences at Liege University in Belgium, she was always drawn to the field of education. After her studies, she volunteered at the Jewish orphanage that had opened at Franciszka 2 Street, and shortly thereafter, at the young age of 26, she became the house manager. Stefa believed in the Maria Montessori educational system as a natural process sparked by curiosity.

When Korczak was appointed director of the new orphanage on Krochmalna Street, he appointed Stefa as his assistant and house mother.

At the orphanage, Korczak and Stefa complemented one another. In testimonies from their students we can read that Korczak was the intellectual and the philosopher and Stefa the woman of action. She showed devotion and concern for the children whilst at the same time being strict and demanding. It was important for her to make them feel at home.

Stefa visited Palestine three times between 1931 and 1938. She stayed at Kibbutz Ein Harod. After the Nazi's occupied Poland, the people of Ein Harod managed to arrange papers for Stefania to leave Poland, but she refused to do so and moved with Korczak and the children into the ghetto. In the ghetto, Stefa was especially active with sick children, setting up a special room for them and sitting for hours besides them and comforting them. On August 5th, 1942, she marched with Korczak, the children of the orphanage, and the rest of the staff to the point of deportation from where they were transported to Treblinka and murdered. As she had done throughout her life, here, too, Stefa devoted her life to others in endless self-sacrifice.

For an expanded biography, see: (pdf file)

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

"Stefa was with us 24 hours a day. We felt her presence even as we slept. We were also aware of how she worried about our every need."(Extract from Yitzchak Belfer's testimony, Yad Vashem, 1992.)

In light of these words what importance do you ascribe to Stefa as Korczak's right hand and long-time assistant in the orphanage?

Educational Values from the Korczak Legacy

1. Respect for the Child

At the center of Korczak's thought was respect for the child. He believed that in any educational setting, the adult-child relationship should be based on mutual respect and dialogue and not imposed from above. Korczak believed that each child is his own person and that every human being has a rich and complete inner world of his own. He believed that childhood is not a period to prepare you for life but it is an integral part of life itself. Everyone deserves to be treated with honor and respect with the inalienable right to develop his own interests.

Every child would develop according to his own interests and abilities and teachers should consistently show respect for the child's hard work. The goal of education is a dialogue and the child has his place in it. The adult should help the child be himself. The laws that the children should respect and obey need to be simple and clearly designed. And adults need to relate seriously to the child's private property. Korczak objected to the use of anything that was not based on dialogue. Many of the values included in his Child's Right to Respect were based on his experience of life in the orphanage. In his book King Matt the First from 1923 and King Matt in the Island from 1931 he tells of a child called Matt, a young prince who lost his father and became a king. The book follows him and what happened to him with his desire to establish a children's kingdom. Korczak based the rights of the children on this. He wrote them in 1929: the right for love and respect, the right to live in the present, the right to be loyal to yourself and the right to make mistakes, among others. UNESCO based its Rights of the Child, published in 1989 based on Korczak's ideas, which provide the essential rights for children of the world.

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

Identify the main points in Korczak's emphasis on respect for the child. How do you relate to his ideas as expressed here?

2. Independence

For Korczak, the heart of the educational effort was to facilitate an independent learner with an active sense of responsibility through the child's own active role in the process.

In the orphanage everybody had obligations and they would take turns in the house keeping. The children, the educators and Korczak himself took part in the different chores such as cleaning and peeling potatoes. There was a rotation of roles with everyone doing all the tasks in turn... When a child finished doing his job he would get a postcard. The picture on the cards would be related to the task. For example, for peeling 200 pounds of potatoes they would get a "flower card"; for looking after small children and new arrivals a "good care card", and more. (From Korczak's, How to Love a Child, p. 353.) The children valued these postcards and took care of them .For every half an hour of work the children would get a postcard. Five hundred postcards of different kinds (there were simpler ones and ones regarded as more valuable) would be worth one postcard of flowers and whoever had 12 flower postcards got a crown. The worker who held a crown had special privileges and was also rewarded with a monetary prize. The postcards gave significance to their daily work and contributed to a positive work ethic.

"My aim is that in the Children’s Home there should be no soft work or crude work, no clever or stupid work, no clean or dirty work. No work for nice young ladies or for the mob. In the Children’s Home, there should be no purely physical and no purely mental workers."1

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

- For Korczak it was important to teach the children to tie their shoelaces, to polish their shoes and to brush their teeth. Why do you think these prosaic daily activities were so important in Korczak's educational approach.

- How do the postcards encourage children to become independent? Why do you think the children so valued these postcards?

3. Democracy and Self –Government

Korczak believed that in progressive education there should be an emphasis on democracy and equality. He asked the children to participate in the management of the orphanage and in this way he implemented equality and self- government. He also established a children's court in the orphanage. Korczak dreamed of releasing the child from dependency on the adults. With regards to the court, he maintained that proximity in age between the accused and the judge would engender justice which is why he attached special importance to the children's court in the orphanage. The court had 5 judges chosen from among the children in a lottery. One of the educators held the position of the court's secretary, but he could not vote. His task was to gather all the testimonies from the children. Children and adults were brought to court for their faults and everyone was committed to stand by the ruling handed down. The rulings were given according to a set of laws and whoever didn’t agree with the ruling, could ask for a review after a month. Informing on other children or bullying and laughing at another child were instances dealt with by the court. Setting new rules for offenses such as being late, making noise or not obeying the teachers and people in charge (also if they were children filling one of their working roles), was an additional function of the court. Korczak accused himself six times for different infractions during the first six months of the orphanage.

"If I am devoting a disproportionate amount of space to the Court, it is because I believe that it may become the nucleus of emancipation, pave the way to a constitution, make unavoidable the promulgation of the Declaration of Children's Rights. The child is entitled to be taken seriously, that his affairs be considered fairly. Thus far, everything has depended on the teacher's goodwill or his good or bad mood. The child has been given no right to protest. We must end despotism."2

Korczak was also innovative with new arrivals. Each new child would receive an older student as a guardian tutor for 3 months. He would explain the rules of the institution to the new child and would defend him from children that might bully him. He would keep a diary where he would write what happened to the new child and his thoughts on the child's absorption.

Korczak and Stefa read them and wrote comments about everything. A year after a new child came to the institution there was a survey among the children to see if he could stay in the orphanage.

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

- How did the child benefit from the children's court?

- Why was it important for Korczak to put himself on the accused bench in the court? What did he want to impart to the children in this unusual step?

4. Freedom to Create

In 1926 Korczak started a newspaper, (The Little Review), as a weekly supplement to the daily Polish-Jewish Newspaper Nasz Przegląd (Our Review) which was one of its kind – it was written for children by children.

Korczak was the editor of the newspaper's supplement for around two and a half years. In it, he published only things written by children. It was important for him because it was "for children, by children". His aim was to create a place for self- expression, a place that would answer their questions and give them further independence. The young writers wrote about subjects that interested them like problems they had with their parents and teachers. There was also a writing competition. The children that wrote in the newspaper got a postcard of recognition for doing so. Korczak said that, "I fully believe that there is a need for magazines for children and written by children..." The Little Review, first edition, 1926. The newspaper existed until the start of the war in 1939.

There was also a children's newspaper in Korczak's orphanage. It covered the court, the judgments and the week's activities.

The children also performed plays. The last play that was performed was "The Post Office" by the Bengali playwright Rabindranath Tagore. The play was staged in the orphanage by the theater class of 1942 during the big deportation taking place in the ghetto. On the 15th of July 1942, Korczak sent out invitations for the performance. The Post Office is a play in two acts. Its story is about a young Indian boy called Amal whose role was played by a child called Abrasha and whose performance left everyone impressed.

Amal had a terminal illness. A post office opened next to his house and Amal waits in his bed for a letter from the king wishing he will fall asleep forever with a smile.

The children in the orphanage identified with Amal and with bated breath they awaited, together with Amal for the king’s letter that would spell redemption.

Korczak wanted his children to learn how to welcome the Angel of Death calmly and this was

his way of conveying this message.

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

- What in your opinion is so special about the children writing their own newspaper?

- Why did he choose to stage "The Post Office"?

5. Games and Play

Korczak recognized the importance of games and play in the lives of children. In the orphanage he organized specific times for play, for excursions and for sport. Group games engendered group solidarity and allowed for expression of the individual. Korczak himself took part in the games and played with the children. Korczak thought that for the child, play is a very serious thing in which he/she invests effort and this was to be noted and not disregarded.

"A game is not so much the child's medium as the only sphere in which he is allowed to display more or less initiative. When participating in a game, the child feels to some degree independent. Everything else is a transient favor, a temporary concession, whereas to play is the child's right." From Janusz Korczak, How to Love a Child, p.158

Points for Discussion in the Classroom:

Think about your group games- what values do they teach?

An Appreciation of Janusz Korczak through Two Poems and One Monument - A Lesson Plan for Teachers

This unit is an interdisciplinary resource to assist educators in teaching the Holocaust. It consists of two poems, presented together with a monument dedicated to Janusz Korczak. The poems and the monument, permit a freer, more varied approach to the subject matter presented in them and enable pupils to be drawn in on different levels. This interdisciplinary aspect creates alternative routes by which different learners can employ different learning skills to deal with the materials presented. The aims of this unit are to:

- Analyze two poems and a monument by exploring the connections between literary and artistic interpretation

- Probe the question of Jewish bravery during the Holocaust

- Discuss universal lessons to be learned from the Holocaust

- Delve deeper into the study of the Holocaust through poetry

- Raise the point of how poetry and art can describe hardship and highlight human experience.

- After the following activities, each child will prepare a poster with a picture, poem or collage where each will express his/her understanding of the fact that Korczak, together with the children, went to their joint deaths.

Suggested Presentation in a Classroom

Rationale

The suggestion to use poetry in the study of the Holocaust is based on the belief that a personal statement, as most Holocaust poetry is, will sometimes trigger initial interest in the subject at hand as well as the historical treatment of the same subject. Poems allow a personal inside view in contrast to the more distanced historian’s account. The human dimension, which is often the focus in poetry will more easily generate attention than the impersonal of the historical portrayal.

Common points of reference between the two poems and the monument can be developed for deeper study.

These two poems about Korczak afford us an additional path of appreciating human behavior in extreme circumstances.

The first poem, entitled simply with the date of Korczak's death, 5.8.1942 with the subtitle, 'In Memory of Janusz Korczak' was written by the Polish poet, Jerzy Ficowski, and it describes only the last hours of the lives of Korczak and the children of the orphanage he accompanied to their common deaths in Treblinka.

First Poem by Ficowski - 5.8.1942

5.8.1942

In Memory of Janusz Korczak

Jerzy Ficowski (1924-2006)

(Translated by Keith Bosley)

What did the Old Doctor do

in the cattle wagon

bound for Treblinka on the fifth of August

over the few hours of the bloodstream

over the dirty river of time

I do not know

what did Charon* of his own free will

the ferryman without an oar do

did he give out to the children

what remained of gasping breath

and leave for himself

only frost down the spine

I do not know

did he lie to them for instance

in small

numbing doses

groom the sweaty little heads

for the scurrying lice of fear

I do not know

yet for all that yet later yet there

in Treblinka

all their terror all the tears

were against him

oh it was only now

just so many minutes say a lifetime

whether a little or a lot

I was not there I do not know

suddenly the Old Doctor saw

the children had grown

as old as he was

older and older

that was how fast they had to go grey as ash

Points for elaboration:

- The phrase, “I do not know” repeats 4 times in the poem. Why do you think the poet did this? Can this be understood as our inability to understand what they were going through?

- What does the poem say about Korczak in the 2nd and 4th verses? What did he give the children from himself? What is he going through as a human being?

- How does the poet portray the problem with the dimension of time in the 5th verse?

- How is the phrase, "death is an equalizer" portrayed in the last verse?

- In your opinion, what is the message the poet is trying to convey in this poem?

- Pupils could choose various phrases from the poem and explain their poetic power in describing the hard reality and the hardship Korczak was coping with, for example:

- gasping breath

- numbing doses

- older and older

- In your opinion, what is the message the poet is trying to convey in this poem?

In the conclusion of the activity, Korzcak’s heroism has to be elucidated with the fact that he chose not to save himself through his connections but decided to go with his orphan wards to their joint deaths in the gas-chambers.

*The figure from Greek mythology, Charon was responsible for ferrying the dead souls across the river Styx into the netherworld.

The teacher should ensure pupil comprehension of Korczak leading orphans to their death, whereas Charon is leading the (already) dead to a final repose.

Second Poem by Szlengel - A Page from a Deportation Report

The second poem was written by Wladislaw Szlengel in the Warsaw ghetto. It describes in detail the last procession of Korczak with the 200 orphans through the ghetto streets to the point of deportation. Szlengel was very well known in the ghetto and public readings of his poems helped bolster morale in a very difficult reality for the ghetto inhabitants. He died in the ghetto during the uprising in 1943.

It is a very long poem and we present below a few verses translated into English.

1. Today, I saw Janusz Korczak

As he and the children took their last walk.

Dressed in clean clothes

As if on a garden stroll to enjoy the Shabbat.

……

2. The face of the city turned anxious

Like a torn and defenceless giant.

Empty windows searching the streets

As in eye-sockets vacant and lifeless.

…..

3. And the children lined up in orderly fives,

Not one pulled out from his line.

Orphans, these – with no chance

Of a bribe and reprieve.

…..

4. Janusz Korczak marched forward with no hesitation

Bare-headed, eyes focused, gaze firm.

A little child clutched his one pocket

With two more held safe in his arms

…..

5. Someone approached at a run,

Document in hand, he proclaimed:

Sir, Herr Brandt* here has signed your release!

At which Korczak simply marched on in disdain.

……

6. All his life he had spent

Creating some warmth in their world,

How now could he leave them to go

The last road in their lives all alone.

The following is a list of themes that Szlengel presents in these verses from the poem and one suggested activity is for the pupils to identify the theme in the verses, indicate the verse number and explain in his words how the theme is reflected in the verse chosen. Possible subjects are: Adult responsibility and love, Inequality of opportunity in a ghetto, The anxiety of impending doom, The ultimate heroic response.

The table below is one way of collating this exercise. The teacher could employ group work on the table thus enabling pupil discussion on the two poems and the monument appearing below.

| THEME | VERSE NO |

| Adult responsibility and love | 4,6 |

| Inequality of opportunity in a ghetto | 3 |

| The anxiety of impending doom | 2 |

| The ultimate heroic response | 5 |

- In your opinion, what is the message the poet is trying to convey in this poem?

* Karl Brandt (1904-1948), high ranking SS officer responsible for the area of Warsaw.

The Monument of Korczak at Yad Vashem

A class discussion on the different elements in the monument could be held with the pupils. Suggestions of elements to focus on are: the children's gaze, Korczak's gaze, Korczak embracing the orphans and a joined fate. In addition, the children can now compare the two poems with the monument. A table might help the pupils organize the elements more clearly and compare aspects of the monument and the poems.

For example:

Suggested connections to be made by pupils

| The Monument | Ficowski's poem | Szlengel's poem |

| Korczak embracing the orphans | Verse 3: the fact that he is taking care of them by cleaning their heads of lice | Verse 4: the physical closeness of children clinging to an authority and protective fatherly figure |

In your opinion do the poems and the monument present the same picture of Korczak on his path with the children to their joint deaths?

Now the students can proceed to prepare a poster with a picture, poem or collage where each will express his/her understanding of fact that Korczak, together with the children, went to their joint deaths.

![A postcard from the youth and children's weekly "Maly Przeglad" [The Little Review], given as a memento to Edwin Markuze. Dated May 1927 A postcard from the youth and children's weekly "Maly Przeglad" [The Little Review], given as a memento to Edwin Markuze. Dated May 1927](https://www.yadvashem.org/sites/default/files/styles/main_image/public/picc.jpg?itok=fsepUJHw)