Grades: 7 - 9

Duration: 1 - 2 hours

Didactic Objectives

- Examine primary resources including testimonies and photographs relating to liberation and survival.

- Think about the meaning of “liberation” after the Holocaust: the saga of liberation was not a happy ending to a sad story, but a tragedy in and of itself.

- Gain insight into how Jews who had survived tried to put the pieces of their broken lives back together, and some of the difficulties they encountered in doing so.

Introduction

World War II ended in May 1945, after six years of bitter fighting. There were victory celebrations throughout the streets of Europe. The first of the Nazi camps to be liberated was Majdanek, in July of 1944, and the rest of the camps were liberated by the spring of 1945. At first glance one might assume that after all the suffering, liberation would be a moment of great joy. However, the immense difficulties and pain of the Jewish survivors presented a different reality.

The story of how those who survived the Holocaust managed to return to life after liberation is not a happy ending to a tragic story; it is actually the final chapter of the tragedy. After years of terror, physical and mental abuse, and constant fear, the survivors finally came face to face with the fact that the world they had once lived in, along with their families, friends and communities, had been irretrievably lost. Somehow, they had to manage to pick up the pieces and begin new lives.

What Was Liberation?

During World War II, Jews who lived in Germany or in countries that had been occupied by Germany were imprisoned in labor camps, concentration camps, and death camps. They were liberated from these camps by Soviet, British and American soldiers in 1944 and 1945.

The first concentration camp to be liberated was Majdanek. The prisoners in Majdanek were liberated by Soviet troops in July 1944. Soon thereafter Soviet troops reached other Nazi camps, and freed their inmates. British and American troops reached Nazi camps in the spring of 1945, liberating tens of thousands of prisoners.

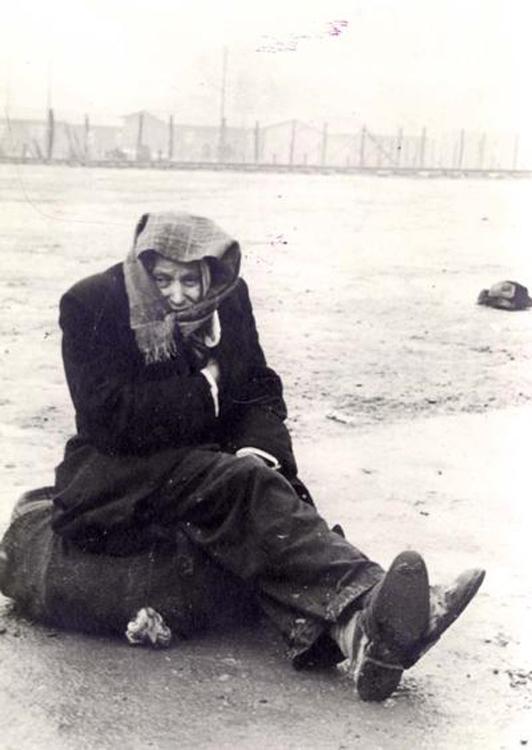

These prisoners had been living under extremely harsh conditions. Many were starving and others were very sick. Many of the people who had been liberated had survived "death marches," forced to march over long distances. The death marches occurred towards the end of the war as the Allies advanced on the German army and the Nazis tried to move prisoners further west into Germany. The German leadership believed that the Third Reich would survive the war. They therefore attempted to move concentration camp prisoners within Germany's borders, so that they could still be exploited for slave labor. Upon entering Auschwitz-Birkenau, Soviet soldiers found only 7,650 prisoners. Most of the 58,000 remaining camp prisoners had been sent on death marches at the end of 1944. Prisoners were abused and sometimes killed by the guards accompanying them on these marches. Approximately 250,000 concentration camp prisoners died on death marches.

Other than survivors of the camps, some of those liberated had been hidden during the war or had masqueraded as Christians with false identity papers. Still others were surviving ghetto fighters, partisans and those who had fled to the forests.

Colonel Lewis Weinstein, a member of the US Army, liberated Jews who were in Nazi camps. He recalls:

"… We had heard all kinds of rumors and stories, but they were so horrible that they were indescribable; we just couldn't believe them. I had a great guilt feeling when I actually found out about what happened in these camps. I had talked in terms of possibly a few thousand having been murdered, but thinking in terms of six million... murdered - I was obviously very much taken aback."

Father Edward P. Doyle, a chaplain in the US Army during WWII, participated in the liberation of Nordhausen. He recalls:

"I was there. I was present. I saw the sights. I will never forget. You have heard the story many times before. On the night of April 11, 1945, my division, of which I was the Catholic chaplain, took the town of Nordhausen. The following morning, with the dawn, we discovered a concentration camp. Immediately the call went out for all medical personnel that could be spared, to be present. […] On that morning in Nordhausen, I knew why I was there. I found the reason for it - man's inhumanity to man. What has happened to that beautiful commandment of the Decalogue, the commandment of God to love one another?"

Eva Goldberg was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and Horneburg camps, and was liberated at Salzwedel, Germany, by American soldiers. She recalls:

"And what I remember most is the convoys of Americans who were standing on both sides of the road and looking at us. They did not believe what they were looking at!"

Classroom Discussion:

- How do Colonel Weinstein and Father Doyle describe their experiences of liberation?

- What does Eva's testimony add to your understanding of Colonel Weinstein's and Father Doyle's testimonies?

Notes for the teacher:

Note the palpable shock of Colonel Weinstein, even after the event. Recall this is a man who has seen combat. Liberator testimony is another angle in describing this moment of liberation. The question of how these liberators would see - literally and figuratively - as well as treat the survivors was crucial, as this was a tremendous junction for the survivors, who had just endured the Holocaust. That they were suddenly receiving initiated treatment - on this, see below - was a novelty in and of itself. Note the ethical angle that arises in both accounts.

What Did Liberation Mean for Jewish Survivors?

Liberation should have been a happy day for the survivors. Finally they were free of the constant fear of death they had lived with for so many years. For the Jewish survivors, however, liberation had come too late. Entire communities in Eastern Europe, especially, had been wiped out and all their Jews exterminated. Over 90% of the Jewish community in Poland, the largest in Europe, had perished.

In Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the Balkan States, the outcome was nearly the same. The Jews of Western and Southern Europe also suffered terribly, though the proportion of those exterminated was lower. In many cases, whole families had been slaughtered, and only single members were left. A survey taken by the Organization for Jewish Refugees in Italy, for example, found that 76% of the Jewish refugees had lost all of their immediate families and all of their relatives, and were the sole survivors from their families.

More than anything else, however, with liberation the survivors were struck suddenly by the immensity of their losses. Up until liberation, survivors had expended all their efforts on the struggle to survive: they scavenged for food, they tried to protect themselves, they lived from minute to minute. This struggle to survive didn’t leave room to focus on the world they had lost: their family and friends, their occupations and habits, their neighborhoods and their possessions. Suddenly they were confronted with a new reality. Their families were gone, and their lives would never be the same. An almost superhuman effort was needed to pick up the pieces of their broken lives and to start over again. While the rest of the world was counting the dead, the Jews were counting the living.

Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman, a member of the underground who fought, among other battles, in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, testified:

“That day, 17 January, was the saddest day of my life. I wanted to cry, not from joy but from grief. [..] How could we be happy? I was completely broken! You'd kept yourself going all the terrible and bitter years, and now... we were overcome by weakness. Now we could suddenly allow ourselves to be weak [..] Ultimately there is an end to war. We had lived all that time with a certain sense of mission, but now? It was over! What for? What for? [..] I had never cried; they had never seen me depressed, not once; I had to live strongly, but on 17 January… it’s not easy to be the last of the Mohicans."

Yosef Govrin was born in 1930 in Romania. He was deported to various ghettos and camps in Transnistria. Yosef was liberated by Soviet soldiers in December 1944. He recalls:

"The devastation caused by the war and the fact that I was an orphan came to me very forcefully on Victory Day. I saw the destruction that the war had wrought much more realistically, I suppose, than I had before. The destruction had been all around me day and night, but only on Victory Day did I notice it on the street where I was walking…It was then, as a boy, that I grasped the full scale of the destruction…and really, Victory Day is engraved in my memory to this day as a day of…not as a day of celebration!"

Eva Braun was born in 1927 in Slovakia. During WWII she was imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau, and liberated by US soldiers. Eva recalls:

"You were praying all those months to be liberated and then it hits you all of a sudden - here you are free. But after it sank in, the freedom - I am speaking for myself - I realized that I was hoping the whole time that I would see my father and maybe, hope beyond hope, my mother, although I knew that this was not a realistic hope. But my father, I was sure I would meet him. I was positive. But still there were doubts, and I realized that I had to start thinking about the fact of what would happen if I would not... Freedom is relative. Very much so. The thought of the future weighed very heavily on me. Obviously we knew that it was no longer our problem but still we have to make a future for ourselves and how would we make that future?"

Miriam Steiner testified:

"[..] The great crisis had not yet hit us. It began when my cousin came home a few days later. I barely recognized him, because that kid, that big slob, had two big ears, a big nose and two cavities for eyes. He began to recover from his "Musselman" condition. For the first time I cried, I fell on him and I cried at how he looked, because then I suddenly woke up. He was the start of my crisis, of the crisis of ours as a whole... He embraced me and said only this: "You should know one thing, don't wait for your father and your brother." He repeated that many times [..] "Now we began to realize the enormity of the loss, we began to understand that Grandfather and Grandmother and hardly any of our relatives had returned, only that one cousin, and his father also returned later on. People said we shouldn't wait for them, but the truth is that we waited all the time for my father. And I only want to say that I often look around, as though I am still searching... not for Father, it is my brother for whom I am still looking all the time. I know it is completely unrealistic, because formally I am not searching, I.. I cast about with my eyes..."

Classroom Discussion:

- Why do you think Yitzhak Zuckerman, Yosef Govrin, Eva Braun and Miriam Steiner did not feel that liberation day was a day of celebration?

- Many prisoners survived the Nazi camps by focusing only on their most immediate daily needs, and thinking about almost nothing else. How do you think this situation affected their experience of liberation?

- One of the greatest difficulties that liberated survivors faced was intense loneliness. Prof. Hanna Yablonka, a Holocaust historian and the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, describes her mother's sentiments upon graduating from nursing school, a few years after the Holocaust. According to Hanna, her mother was elated that she had finished her degree, and yet plagued with an overwhelming sense of loneliness - she truly had no one with whom to share her news. What do you think is the difference between the loneliness that we all sometimes experience and the loneliness that Holocaust survivors felt after liberation?

The Allied soldiers cared for the survivors they had liberated. They fed the survivors and gave them the medical attention that they so desperately needed.

Ephraim Poremba was born in Poland. Ephraim was deported to several Nazi camps, and he was liberated by the US Army at the age of twenty. He recalls:

"The Americans organized a hospital, they started doing tests, they set up tents with water and showers. We washed, they gave us soap. When did I last wash? I couldn't remember…First of all hot water; whoever saw hot water? It was a dream. As much hot water as you want, to wash with soap, with soap! You could even wash your head, your body, it was heaven, it was heaven on earth!"

What Did the Survivors Do Following Liberation?

By the end of 1945, those Jews who had managed to survive forced labor camps, concentration camps, extermination camps, and death marches, or who had survived in hiding, in forests, or with the help of local individuals (later to become Righteous Among the Nations), wanted only to go “home.” Some found that they had no homes or families left. Others found that going home involved a dangerous journey through chaotic, post-war Europe. Those who succeeded in reaching their old homes had to confront a new reality: the local populations in their homes, particularly in Eastern Europe, were antisemitic and hostile toward Jews, and saw their return as unwelcome.

Shoshana Stark testified:

“I went home. I didn’t have anywhere I could stay... The gatekeeper was living in the house and wouldn’t let me go in... I also had aunts and family. I went to see all their apartments. There were non-Jews living in every one. They wouldn’t let me in. In one place, one of them said, ‘What did you come back for? They took you away to kill you, so why did you have to come back?’ I decided: I’m not staying here, I’m going.”

Avraham Dobo (Dabri) wrote:

“After some initial difficulties, I got what I needed and set out on the one thousand kilometer journey, which took three weeks or more. I arrived in my town, and just as I got off the train I met a man, a Christian acquaintance, whom I had gone to school with. I asked, “How are you?” He said, “Your sister arrived a week ago.” I knew where she lived. I went on foot. My clothes were half military and half civilian. I didn’t have any other clothes but one shirt – just my rumpled pants and an army jacket. This is how I came home. I walked into my sister’s house. I met her there, and she asked, “Who are you looking for?” Two years before, we said goodbye – now she doesn’t know me. I was skin and bones, with no hair. I looked like I could be ten years old and I could be eighty. I spoke with her a few minutes – I wanted to know what was new. Then, we burst out crying.”

Shmuel Shulman Shilo was born in Poland in 1928. He lived in the Lutsk Ghetto, and immigrated to Israel in 1946. He testified:

“Suddenly I’m standing in the middle of the city [..] and I ask myself, “So what? Home – gone, family – gone, children – gone, my friends are gone, Jews – gone. Here and there would be a Jew I hardly knew. This is what I fought for? This is what I stayed alive for? Suddenly I realized that my whole struggle had been pointless, and I didn’t feel like living.”

Classroom Discussion:

Note for the teacher:

Note the difference between not knowing whether you have a home, and/or a family left, and finding out that you don’t. In Shoshana Stark, testimony, the rejection by locals in coming back to what had been the survivors’ homes, was a different, external, blow. Shmuel Shulman’s testimony conveys the loss not just of family but of community, of some kind of anchoring to a “normal” life, and what the realization that it’s no longer there - implies.

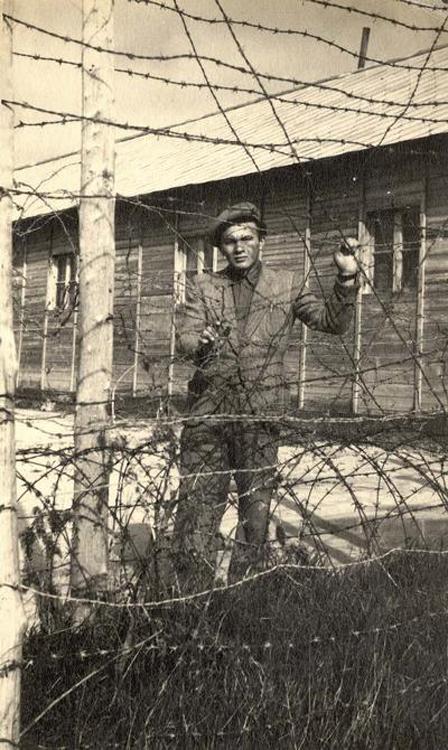

The Displaced Persons (DP) Camps

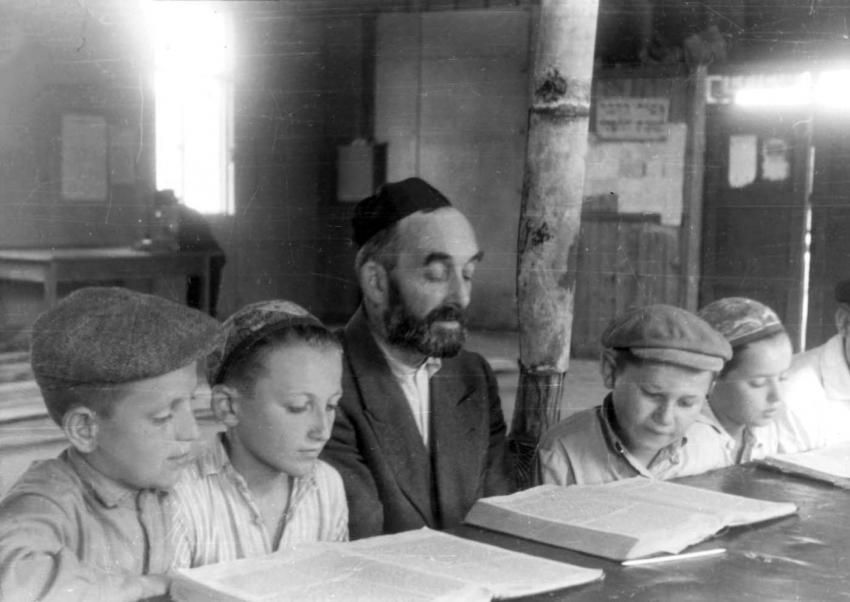

Understanding that the Jewish survivors could not, in most cases, be repatriated to their homes, Allied forces and the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), an organization created in anticipation of a great refugee crisis when World War II ended, cared for them in improvised shelters throughout camps in central Europe known as Displaced Persons' (DP) camps. Conditions in these camps, especially at the beginning, were very difficult. Many of the camps were former concentration camps and German army camps. Survivors found themselves still living behind barbed wire, still subsisting on inadequate amounts of food and still suffering from shortages of clothing, medicine and supplies. Death rates remained high. Yet, despite the wretched physical conditions, the survivors in the DP camps transformed them into a flurry of cultural and social activities. More than 70 Jewish newspapers were published. Theaters and orchestras were established.

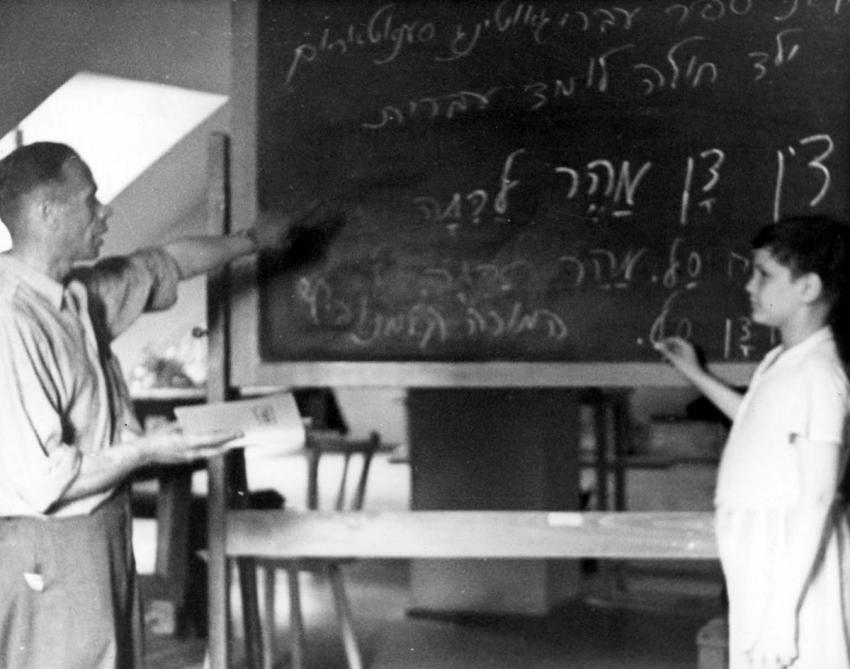

Educational institutions were set up. Commemoration projects were initiated. The survivors had a strong drive that led them to try to find new meaning in their lives.

An emissary from Palestine described the DP camps as follows:

"There are always people out in the narrow street, usually young men, wandering around and looking for something. I feel that they are looking for some meaning in their lives. They get up in the morning and don't know why. The day passes and night falls, and another day and another night passes by. And if you should once look into the eyes of one of these young men, and knew how to read his soul -- you would understand that his soul is still wandering in his past, he is remembering the past and yearning for tomorrow. The present is unnecessary, serving only to bridge the gulf between the old life and the future. The sense of impermanence is tangible in every step. There is no stability -- neither material nor spiritual. Yesterday was spent in hell on earth, tomorrow will be in a heavenly paradise -- and in between there is nothing but emptiness and inaction.

The camp is full of posters -- here a wall newspaper and there an announcement board. Endless posters, flags and slogans. To the stranger who enters, life here seems active and full of culture and spirit. But on closer inspection, you will shudder at the terrible abyss opening at your feet. There is something special in the sounds of music, the dances and the cafe life, a sort of frightened and irritable undertone.

Everything is seen in too sharp a light and is heard too loudly. Everything is beyond the human scale; and if you have breathed that air, you will understand that here live people who have already experienced their deaths long ago. Camp eyes are still saturated with the visions of suffering, camp lips smile a cynical smile, and the survivors' voices cry, 'We have not yet perished'."

More than anything else, though, the Jewish survivors had a deep desire for human relationships in order to banish their despair and loneliness. Many of the survivors were young men and women between twenty and thirty years of age, who were all alone in the world. They formed couples and married quickly. One DP who had lost his family proposed to another DP with these words, “I am alone. I have no one, I have lost everything. You are alone. You have no one. You have lost everything. Let us be alone together.”

The survivors were in a rush to have children and to raise new families as the symbol of the future – their own future and that of the Jewish people. In the DP Camp at Bergen Belsen alone, 555 babies were born in 1946. The birth rate in the camps was among the highest in the world. Eliezer Adler was born in 1923 in Belz, Poland. He spent most of WWII in a forced labor camp in the Soviet Union. After the war Eliezer spent three years in DP camps. He recalled:

"...This issue of the rehabilitation of She'arit Hapleta ("surviving remnant"), the Jews' desire to live, is unbelievable. People got married; they would take a hut and divide it into ten tiny rooms for ten couples. The desire for life overcame everything - in spite of everything I am alive, and even living with intensity.

When I look back today on those three years in Germany I am amazed. We took children and turned them into human beings, we published a newspaper; we breathed life into those bones. The great reckoning with the Holocaust? Who bothered about that... you knew the reality, you knew you had no family, that you were alone, that you had to do something. You were busy doing things. I remember that I used to tell the young people: Forgetfulness is a great thing. A person can forget, because if they couldn't forget they couldn't build a new life. After such a destruction to build a new life, to get married, to bring children into the world? In forgetfulness lay the ability to create a new life... somehow, the desire for life was so strong that it kept us alive…"

In this quotation, Abba Kovner, a leader of the Jewish underground and partisan movements in Lithuania, reflects on the activities of survivors after the liberation:

"Nor would I have found it surprising if they had turned into a band of robbers, thieves, and murderers […]. They had come forth hungry, dressed in tattered rages, broken and defeated, and the first thing they wanted was to seek the basic things: bread, shelter, and work. All of this could have deteriorated into the misery of their so-called rehabilitated lives."

Classroom Discussion:

-

In the camp, despair at what the survivors had just gone through reside side by side with a flurry of social and cultural activity. Why do you think that is?

-

Abba Kovner notes how he would not have been surprised had the survivors turned into criminals, in attempting to survive. Can you speculate why you think this did not happen?

Note to the Teacher:

One can see the flurry of activity as a response to a need created by the very same loss. The loss of one’s previous life, and the realization thereof, did not in all cases mean the extinction of those needs - for community, for cultural life, for something to strive for - that are natural to most of us. One can only speculate on the second question, but we may consider that the care, however bare-boned and threadbare, that the survivors received in DP camps, played a role. At this point they were not, as it were, completely abandoned - in stark contrast to how many had felt during the Holocaust.

The Bericha: Emigration from Europe

The survivors in the DP camps in Europe focused their efforts on emigration from Europe to build new and productive lives elsewhere. Though they may have hoped to return to their homes, the rampant antisemitism and attitude of the local populations forced them to reach the conclusion that there was no longer any place in Europe for the Jews. Many of the DP camp residents strongly declared their intention to move to Palestine. The movement of the Jewish survivors out of Europe and towards then-Palestine was called the “bericha”, Hebrew for “escape.” At this time, however, Palestine was under the British Mandate. Highly restrictive immigration policies remained in effect until May 1948, when Israel became a state. Many of the survivors were forced to try to reach Palestine illegally. Some were intercepted by the British, as described in the testimony of Rachel Ben-Chaim. Rachel Ben-Chaim was born in Hungary in 1926. During WWII she was imprisoned in Auschwitz-Birkenau and the Stutthof camp. Rachel survived a death march, and in January 1945 she was liberated by Russian soldiers. Rachel immigrated to Palestine in January 1946. She recalls:

"We crossed the borders using several strategies, at least four or five borders. Twice we were given forged papers... We crossed one border on foot. I was carrying someone's child. We crossed another border in a goods train. They put us in one or two wagons and closed us in. The empty goods train crossed the border to bring in goods, and we were in the wagons...Later we reached Villa Emma in Italy, and we were there for a long time without doing much. We left there later, and this is how it was: they loaded us onto lorries and tied down the tarpaulins over us. The Brigade soldiers [Jewish soldiers from Palestine, who technically belonged to the British Army but tried to help the Jewish survivors reach Palestine] closed off the road, saying that only the army could go through, and we were the 'army'. They took us to the harbor... they almost threw us [onto the ship], because it was all very urgent. We had to get into the ship's hold very quickly, more than nine hundred of us. They just poured us into the ship...

...When the ship anchored off the coast of Palestine the English discovered us. Warships surrounded us and then something happened that I shall never forget, even though 47 years have gone by since then. We dropped anchor in the middle of the sea, we hoisted the national flag [the blue and white flag with the Star of David, later adopted as the flag of Israel] to the top of the mast, and we felt that the entire Jewish people was standing on the Haifa shore, because the deck was full... you don't forget something like that, it gave us the strength to endure many difficulties".

One third of the liberated survivors chose to emigrate to countries other than Israel. They moved, by and large, to the United States, Canada and other Western countries.

Conclusion

The stories of liberation, and the events that followed in the lives of Holocaust survivors, do not have a simple, happy ending. The trauma experienced by those who were subjected to the Nazi regime was so great that it remained with them, and continues to accompany them in one form or another, throughout their lives.