Rationale

RationaleArtworks offer another viewpoint for understanding history. Art goes beyond analysis of historical perspectives as it offers unique, personal insights into the human conditions and experiences, communicating emotional states and thoughts to viewers through forms, colors, sounds, and words.

Art can be used as a vehicle for examining historical events and gaining new perspectives on various historical subjects. This teacher's guide is designed to show educators how to use art to teach history.

Most artworks are records of the past and can be used as education complements to traditional written sources as part of the history curriculum.

In some cases, art was created with the express purpose of documenting. Educators can encourage students to create their own works of art to communicate the themes and content they learn about a particular historical era, event, or individual.

Art offers a different approach to Holocaust studies, with a potential to deepen our knowledge and understanding of this dark chapter in modern history. Art is an effective and captivating tool that educators can use when teaching about World War II, the Holocaust and its aftermath in all its dimensions and ramifications.

Educators may find that the world of art offers their students a richer and more accessible path to processing this complex subject matter, keeping in mind that artworks that are used when teaching Holocaust-related subjects need to be placed and viewed within their historical context.

Artworks Created during the Holocaust and its Aftermath

Artworks Created during the Holocaust and its AftermathArtists created artworks during the Holocaust in various ghettos, camps, and hiding places. In each one of those places the circumstances were different. In some cases artists were commissioned by the ghetto Jewish leadership, in others, by the Nazi authorities in concentration camps, while some artists created secretly to fulfil their need to document events but also to express their deepest feelings and fears.

Artists would document atrocities and events, everyday scenes in ghettos and camps, portray their fellow inmates, paint landscapes in and around the places where they were stationed or encamped, etc. However, they also created works for a variety of personal reasons, sometimes in order to confirm their own existence as individuals or to escape the harsh reality around them.

Works of art created in the aftermath of World War II can also serve as powerful tools in learning about the Holocaust through the eyes of those who survived its horrors. These works reveal the sense of bewilderment and shock, and not only joy, at liberation. They also express the confusion of survival and the survivors' hopelessness, despair, and alienation – both within themselves and the outside world.

Liberation

Although new life began with the liberation for survivors of the Holocaust, the physical and psychological traumas did not disappear once the war ended. The feelings of loss, grief, and emotional muteness expanded, in some cases completely taking over the survivors' mind, leaving little room for other sentiments. It was more than a personal anguish, as many survivors were sole representatives who remained from destroyed communities and large families. For the majority, only after the liberation could they convey the tragedy, loss, and the scale of the Holocaust.

The wartime was characterized by an absolute absence of everything that had been a part of the lives of European Jewry prior to the war. The period turned into a constant fight for survival, causing emotional, physical, social, and material suffering. After the liberation, without families, homes, and for the most part, without work and incomes, the survivors faced utter destitution.

In this section we will try to grasp the complexity of the survivors' experience of the liberation through fine arts.

As the reactions of the survivors to the recounting of the liberation differed, the artworks that we will present are very different in nature. On the one end are works that convey a sense of pointlessness, and on the other end are those that feature hope of new life. In examining the various aspects of liberation and its aftermath expressed through art, we propose a different insight to understanding this historical event and its broader context from a personal angle.

We hope to provide inspiration for actively engaging educators and learners with selected examples and through suggested discussions.

Artists’ Response to Liberation

We will explore works by three artists of Jewish descent: a survivor of a concentration camp, a survivor of a ghetto and a liberator-soldier of the Red Army, who in their works addressed some of the aforementioned issues and existential dilemmas that appear in artworks following the liberation.

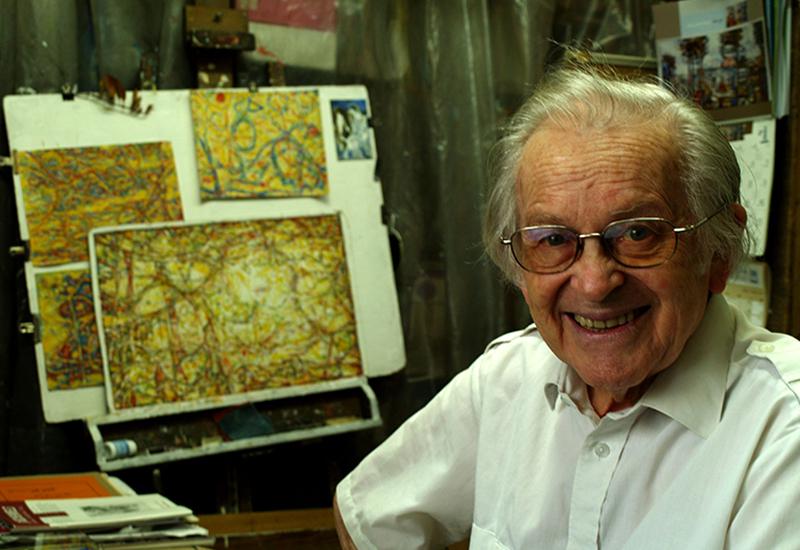

Yehuda Bacon

Yehuda BaconYehuda Bacon (1929–) was born in Moravská Ostrava in Czechoslovakia. In September 1942 he was deported with his family to Theresienstadt. While there he lived in Jugendheim (youth home) and was a member of a group of boys who published a secret magazine called Vedem (We Are Leading). In the camp he studied art with the imprisoned artists Leo Haas, Otto Ungar, and Karl Fleischmann. In 1943 Bacon and his family were deported to the “family camp” at Auschwitz. In 1944 he was transferred to the men’s camp and assigned to a labor group that was gathering the murdered inmates’ belongings, and collecting the victims’ ashes for dispersal. Prior to the evacuation of Auschwitz, Bacon was sent on a death march to the Blechhammer, then to the Mauthausen, and finally, to the Gunskirchen camp, from which he was liberated. Following the liberation, he drew sketches of the crematoria and gas chambers at Auschwitz, which would later serve as testimony in Eichmann’s trial. After immigrating to pre-state Israel, he studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art, where he eventually became a faculty member.

Most of Bacon's paintings depict events he witnessed as a boy in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. The artwork we choose to present is dedicated to Pitter Přemysl, a Czech pedagogue, social worker and evangelical preacher, who rescued a number of Jewish families during the Holocaust. After the liberation, as a member of the Committee for Christian Aid to Jewish Children, Přemysl took upon himself to transfer Jewish children survivors from German concentration camps as well as those from Czech internment camps to rehabilitation centers where he provided them with health and social care. Yehuda Bacon arrived at one of these centers, the Štiřín Castle near Prague, in the summer of 1945 and remained there until spring 1946. Pitter Přemysl was proclaimed Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem in 1964.

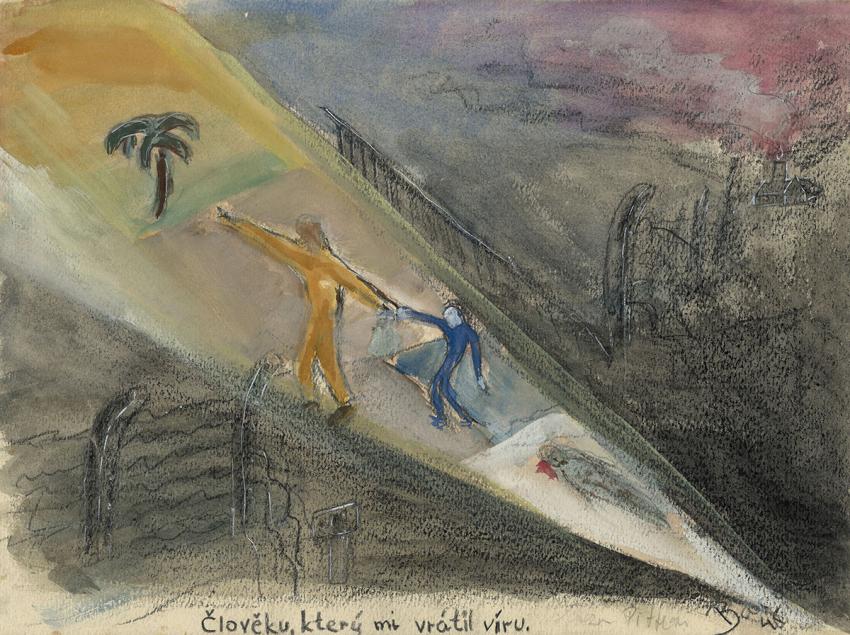

A drawing entitled "To the Man who Restored my Belief in Humanity" features two figures placed in a landscape divided diagonally by barbed wire into two sections. A bent small figure colored in blue is Bacon, who is being led through a ray of light by a straight-standing tall yellow figure that represents Přemysl. He is pulling Bacon from the darkness of a death camp, represented in the bottom section, towards a captivating landscape in hues of yellow and green in the upper section of the picture. The color-scheme and the motif of a palm-tree, create a strong reference that a new life awaits young Bacon in the Land of Israel. Bacon in this work refers to the psychological and physical rehabilitation he underwent as a survivor after the liberation. From a young man who had lost trust and faith in humanity, through a healing process led by Přemysl, he gained a sense of hope and the belief that a better world is possible.

Discussion questions:

- Analyze elements of the painting. What in your opinion may they mean in terms of Yehuda Bacon's "state of mind"?

- What is happening to the boy in this picture? How does he react to what is happening to and around him and why in your opinion is he reacting this way?

- Who or what do you think is the figure behind the boy? Does it look like a real person? What feeling does this figure evoke in you?

- What is the symbolism of light and dark, bright and light colors, and the division of the background into two sections (lower and upper) in this drawing?

Note to the Teacher: Bacon created a powerful iconography that includes a number of motifs that can lead to a discussion about the artist’s state of mind when creating this work. Some possible topics to discuss: what the ray of light may tell us about how Bacon sees his liberation; what is the meaning of the strong direction of the light? Perhaps it tells us that his rescuer is helping him focus on moving away from thoughts of his past, and focusing - like the light - on what is here now and what will be in the future. What is the meaning of the bloodied character behind the boy? Does its proximity to him convey a feeling that it is constantly "right behind his back?" What is the symbolism of leaving the place, when the place essentially stays there - it does not disappear. Analyze a contrast in colors and motifs: black/grey/blue vs yellow/green, barbed wire as a symbol of suffering, imprisonment, and repression vs palm tree, symbol of peace, normalcy, and hope.

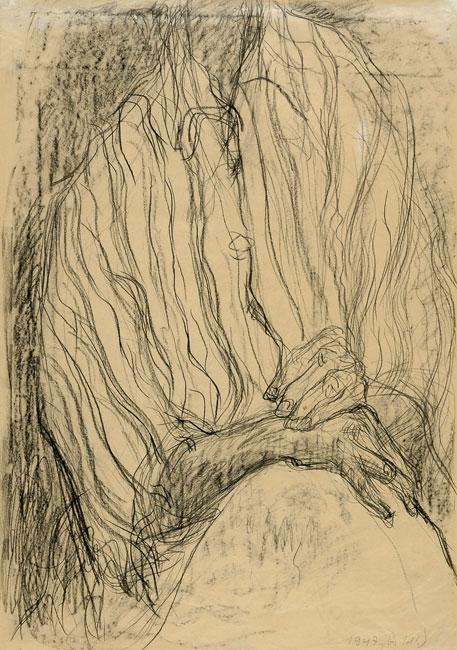

Ilka Gedő

Ilka GedőIlka Gedő (1921-1985) was born in Budapest. She became interested in art from an early age. However, when she reached the age to start her art studies at the Hungarian Academy of Arts, the numerus clausus law, limiting the enrollment of Jewish students in Hungarian universities, prevented her from doing so. She thus studied art with three private teachers of Jewish descent, Tibor Gallé, Viktor Erdei, and István Örkényi-Strasser. The first exhibition of her artworks was organized by the National Hungarian Jewish Cultural Association (OMIKE) in 1940. Following the German occupation of Hungary, Gedő was sent in June 1944 to a compulsory residence in one of the 1,944 yellow-star houses in Budapest. She was moved into the 7th district ghetto in November 1944. When she was summoned for deportation, one of the elderly in the community reported in her place. She managed to find a hiding place in the ghetto where she stayed until the liberation of Budapest on January 18, 1945. After the war, she studied art at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts. She lived in Budapest and exhibited her works world-wide.

A couple of years after the liberation, Gedő creates this powerful "Self-portrait" in which she features herself headless. The focus of the drawing is actually on the artist's upper body and her gnarled hands resting on her knees. She is dressed in a shirt resembling those worn by prisoners at Nazi death camps. However, it seems that underneath this uniform garment there is no body, and the fragile, weightless figure does not seem to reveal its age or gender. In this work, the artist explores her own identity, as a Jew, as a woman, as a restrained human being. This fragmented self-portrait reveals to us the artist's inner collapse and disintegration and her anguish in returning to life.

Discussion Questions:

- The figure is headless. What does this work say about Gedő’s personality/state of mind and sense of self-worth?

- The artwork is titled “Self-portrait”. Why do you think the artist chose to present herself this way? What does it mean to you?

- What do the motifs such as slumped posture, baggy clothes, and cramped fingers, convey about the state of mind of the artist?

Note for the Teacher: Analyze with your students types of line strokes in the drawing: the concrete and the ephemeral, the outer and the inner, and a strong shadow on the left-hand side. What kind of influence do these lines and surfaces have on you and what effect do they have on the overall emotional atmosphere of the drawing? Does the fragmentation of the figure (hands, shirt, lower body, no head) compel you to disclose the drawing section-by-section? If a self-portrait is an attempt to communicate the internal dialogue of the artist, what do these layers of lines tell us? What are the feelings that the work conveys - perhaps of weakness, feeling of being “not up to the task”, resignation, vulnerability? Does a headless self-portrait deliver us a message of dehumanization of the Holocaust victims?

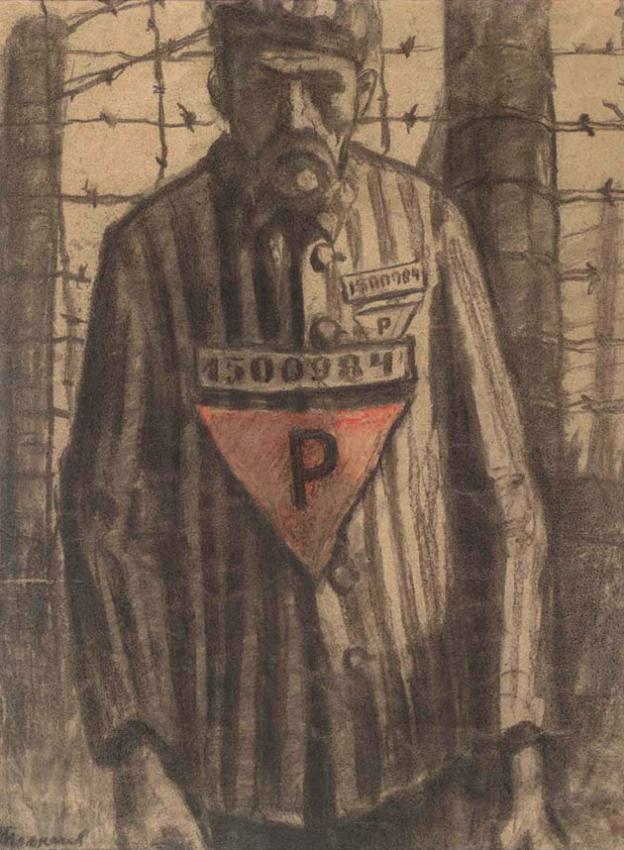

Zinovii Tolkatchev

Zinovii TolkatchevZinovii Shenderovich Tolkatchev (1903–1977) was born in Shchedrin, a small Jewish agricultural settlement in Belarus. He received artistic training first in Kyiv and later in Moscow. As a member of the Young Communist League, Tolkatchev studied at the Communist Institute in Kharkiv. Between the two world wars he was primarily creating official propaganda art. From the outbreak of World War II until 1945, he served as an official artist in the Red Army. He entered Majdanek and Auschwitz with the Soviet army in the summer of 1944 and documented their liberation with a series of artworks depicting the horrific scenes he witnessed in these camps. However, after the War the Soviet authorities denounced him and his art was declared defective.

The drawing entitled "One of the Nameless” was created in the days following the liberation of the Lublin-Majdanek concentration camp by the Red Army on July 23, 1944. They found fewer than 500 prisoners left in the camp, most of them in very poor physical condition, due to the fact that the SS evacuated most of the prisoners to concentration camps further west during the spring of 1944. This work is one of many depictions of survivors that Tolkatchev made in Majdanek. The drawing features a man wearing a prisoner’s striped garb, the red triangle with a letter P and the individual prison number, standing against the barbed wire fence. The face shows distinctive features, which could not possibly be seen without direct observation by the artist. The man’s gaze is ambiguous and the shadows on his face partially conceal an expression which could be downtrodden or aggrieved, or could possibly display anger and readiness to fight.

Discussion Questions:

- Research to find out what type of prisoners wore a red triangle with the letter P on their uniforms. What does this tell us about this particular prisoner?

- The portrayed man is looking directly into our eyes. What internal feelings and thoughts are expressed in his gaze? What does his gaze reveal to us about the prisoner’s state of mind?

- What kind of feeling does the barbed wire behind the figure evoke in you?

- What effect does the red accent on the triangle with the letter P create?

Note for the Teacher: Analyze with your students types of concentration camp badges and what each of them meant. In concentration camps human beings were dehumanized, becoming merely numbers. The man in the picture has distinctive features and is recognizable as an individual human being. That transition from "one of the numbers" to a dignified human being is one of the subjects the artist tries to render in his work. This could be a subject for discussion; about reclaiming a sense of identity after the Holocaust. The vertical composition, and strong and clean lines convey a sense of sombre dignity. By exaggerating the verticality of the composition and focusing on both the figure and barbed wire, the artist forces viewers to look at the prisoner and his surroundings and imagine life inside the camp.