The subject matter of an educational unit on the perpetrators of the Holocaust is fraught with difficulty. The mystery of how some human beings become the mass murderers of others – men, women and children – makes such a unit unnervingly difficult to approach. This holds true for both subject matter and the issues that the educator might seek to convey. Teaching about the perpetrators necessarily forces the educator to walk a fine line between two obligations.

First, it is important to understand the human dimension of mass murder. The victims must be granted the human image and dignity that their executors attempted to deny them. The inherent danger in teaching about the perpetrators’ views and responses alone is that the face of the victim will be lost – albeit unintentionally. The victims’ perspective also needs to be heard and felt.

The second obligation is to understand that the murderers themselves were human beings and that it was human choice and man-made circumstances that led to the murder of six million Jews and millions of others. This must be understood as part of both the historical discipline and moral concern. The study of history is at all times a study of human actions and of the human spirit, even when that spirit has been subverted and has become ineffably corrupt. Moreover, the moral warning signs that the Holocaust must raise for us oblige us to attempt to understand how it is that human beings can reach such a point.

Yet, there is a profound danger in such an effort to understand the darkest recesses of the human spirit. It should be stressed at all times that understanding is by no means equivalent to acceptance, empathy or forgiveness. Rather, it is precisely the moral obligation to reject and to revolt against such conduct that reasserts the historical burden of understanding how it was possible.

Some of the materials here seek to address the choices made by the individuals involved and the ramifications that those choices had for those who fell into their hands. Focusing on the perpetrators’ background and the circumstances that turned them into murderers may at times create the impression that this was a deterministic process in which everything led towards this ultimate end, that the individuals involved had no room for choice and no alternative but to become murderers. The attempt to gain some insight into their conduct does not mean that that conduct was inevitable, or that no other avenues were open to them.

The focus on choices and alternatives means an attempt to explore the wide spectrum of behaviour, beginning with the ideologically committed murderers, through shades of acquiescence and indifference, to those few who took action to oppose the murder. There is an important educational message in pointing out the blurred lines dividing one supposed category from another, and to the choices involved in crossing those invisible lines.

The questions raised by the subject matter cannot provide definitive or clear-cut answers. Faced with the scale of the suffering inflicted by one group of human beings on another, answers fall short of exhaustive explanation. This exploration should both be the beginning of an ongoing process and aim at providing some initial insights into the complexities of human behaviour during the Holocaust.

This unit is part of a series of online educational units on select topics within Holocaust education. In these unique educational environments, we present a variety of teaching aids and auxiliary materials to assist the educator in teaching the subject, offering educators not only the historical information they need, but also the pedagogical tools to facilitate the lesson. The format allows educators to choose from the range of materials offered: lesson plans, presentations, archival materials, filmed testimonies, historical clips, Pages of Testimony and primary source materials (documents, photographs, diaries, maps, etc.), as well as video lectures.

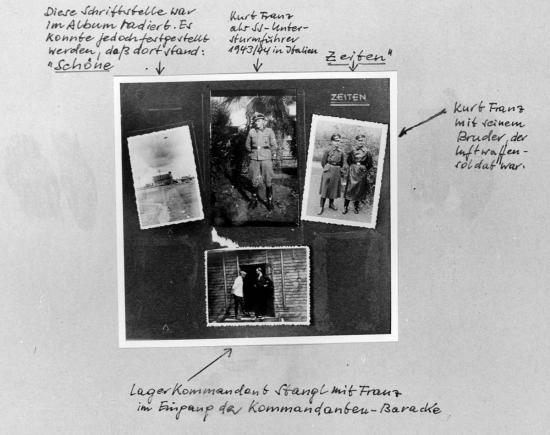

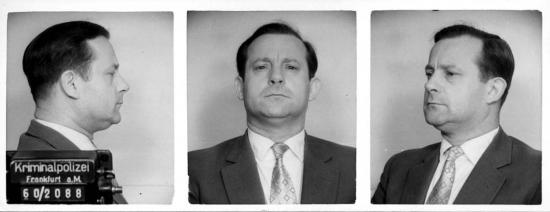

Franz Stangl was born in Austria in 1908. In 1940, he was appointed to the “euthanasia” programme, where he served as head of security at Hartheim, Austria, one of the six killing centres for the mentally and physically disabled. In March, 1942, he was transferred with a group of “euthanasia” personnel to the extermination camps in the East to participate in the destruction of the Jews. Stangl was commander of the Sobibor extermination camp until September of that year. He was then brought to reorganize the camp at Treblinka, which was in a state of total disarray – a task he performed with great efficiency. He remained commander of that camp until it was dismantled following an inmate revolt in August, 1943.

After the war, Stangl escaped from American detention and fled to Brazil. He was extradited to Germany in 1967 and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1970. He died in prison in 1971. While in prison, he was interviewed by Gitta Sereny, a British journalist. The interviews and related materials were published in a book entitled Into That Darkness, a dramatized section of which can be listened to below.

The interview medium, centering around questions and answers between the journalist and a person, adds meanings to the question "how was it humanly possible?" The presentation of the interview with the perpetrator provides us with a wider perspective about the operation of the final solution and the way the perpetrators perceived their victims. In the following recording, the reading of the roles are intentionally reversed, with a woman reading the answers of Stangl, and a man reading the questions of the Sereny. This is intentional, so as to draw attention away from theatrics and towards the words actually being said.

Please listen to the recording, and discuss the questions below.

- How would you describe Stangl’s ability to see human beings as cargo or cattle?

- How do you account for his inability to make a connection between the children who arrive on transports and his own children? Do you think there should be a connection?

- Stangl presents himself as one who was controlled by circumstances and by his superiors. On the other hand, as Gitta Sereny points out, he clearly had choices along the way – something which he himself does not deny. How does he reconcile these two aspects of his account?

For more discussion material, see our unit with teaching guide "How Was it Humanly Possible?".

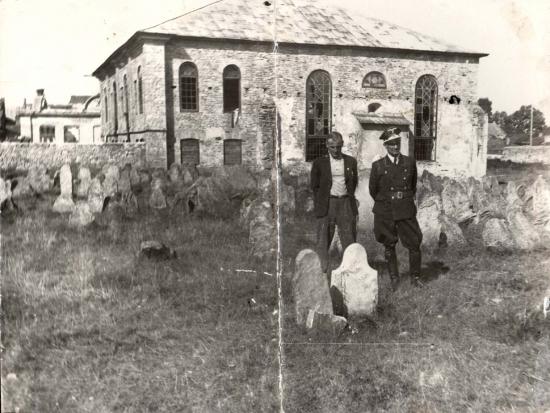

Yad Vashem Photo Archive, 1465

Photographed by an anonymous German photographer in late 1942 or early 1943.

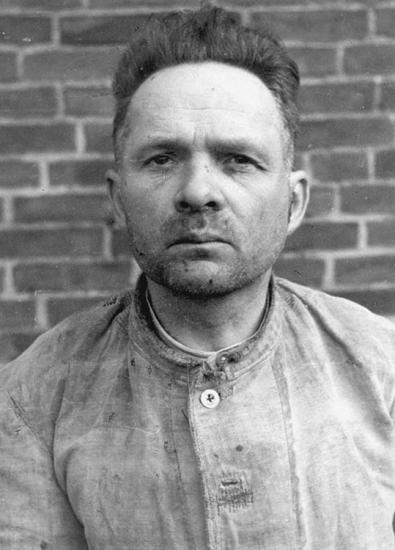

Yad Vashem Photo Archives FA76/103

Photographed by an anonymous German photographer and the end of 1942 or the beginning of 1943.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives FA76/68

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 3380/91

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 149EO3

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 149EO2

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 1893/15

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 1602/457

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 3731/1

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 2572/33

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 1817

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 92AO6

.jpg?itok=68cm7qhE)

7261/399 (Budesarchiv)

.jpg?itok=qKo-r6kq)

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 2791/7

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 39BO2

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 14DO9

The people in the background are on their way to Crematorium II, whose building is just visible on the top center of the photo.

Yad Vashem Photo Archive FA-268/25.

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4522

.jpg?itok=lTe4hPP9)

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4522

.jpg?itok=1AFxeHc3)

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 3179/2

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4613/381

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 5318/260

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 4577/115

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 1448

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 1584/102

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 3678

Yad Vashem Photo Archives, 5318/171

General Keywords

Local Murder

Additional materials:

- The Beginning of the Final Solution

- The Wehrmacht and the Einsatzgruppen Aktionen, 1941

- Instructions by Reinhard Heydrich on Policy and Operations Concerning Jews in the Occupied Territories, September 21, 1939

- Exchange Of Letters Between Reichskommissar Lohse and the Ministry For The Eastern Territories, Concerning The "Final Solution"

- Extract From a Report by Karl Jaeger, Commander Of Einsatzkommando 3, on the Extermination Of Lithuanian Jews, 1941

- Aktion 1005 (Keyword)

- Babi Yar (Keyword)

- Einsatzgruppen (Keyword)

- Jodl, Alfred (Keyword)

- Kaltenbrunner, Ernst (Keyword)

- Keitel, Wilhelm (Keyword)

- Killing Sites (Keyword)

- Ponar (Ponary) (Keyword)

- Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) (Keyword)

- Wehrmacht (Keyword)

The Camp Murderers

Additional materials:

- Signed Obligation by SS Men Taking Part In an Extermination Operation To Observe Secrecy July 18, 1942

- From the Notes of Kurt Gerstein, Engineer Working for the SS, on the Extermination Camp at Belzec

- Kurt Gerstein

- The Eichmann Trial (Online Exhibition)

- Majdanek and Auschwitz Liberated - Testimony of An Artist (Online Exhibition)

- Adolf Eichmann Trial in 1961 (Keyword)

- The Auschwitz Trials (Keyword)

- Frank, Kurt (Keyword)

- Globocnik, Odilo (Keyword)

- Goeth, Amon Leopold (Keyword)

- Greiser, Arthur (Keyword)

- Hess, Rudolph (Keyword)

- I.G. Farben (Keyword)

- Stangl, Franz (Keyword)

- Wirth, Christian (Keyword)