Grades: 12

Duration: 1 - 2 hours

This unit is a new interdisciplinary resource to assist educators in teaching the Holocaust. It consists of seven poems, presented together with original artwork especially created for the unit.

Each poem, together with its relevant painting, permits a freer, more varied approach to the subject matter presented in the poem and enables pupils to be drawn in on different levels. The drawings were created by one particular artist who presents her personal impressions of the poems. This interdisciplinary aspect creates alternative routes by which different learners can employ different learning skills to deal with the materials presented. The aims of this unit are to:

- Analyze poems and paintings by exploring the connections between literary and artistic interpretation

- Probe the question of Jewish identity after the Holocaust

- Discuss universal lessons to be learned from the Holocaust

- Delve deeper into the study of the Holocaust through poetry

- Engage pupils in creating their own art

The suggestion to use poetry in the study of the Holocaust is based on the belief that a personal statement, as most Holocaust poetry is, will more effectively trigger initial interest in the subject at hand than the historical treatment of the same subject. Poems allow a personal inside view in contrast to the more distanced historian’s account. The human dimension, which is often the focus in poetry will more easily generate attention than the impersonal of the historical portrayal.

The choice of poems in this unit covers the whole period – preceding, during and after the Holocaust but the seven poems do not form a composite picture of the Holocaust. They are rather like different colored stones in an intricate mosaic that depict, very personally, different angles of the whole. They are not interlinked or interdependent although of course common points of reference between some of them can be developed for deeper study. A variety of subjects is presented by the poems in this unit. They are outlined in the table below.

| Poet | Poem | Subject |

|---|---|---|

| Primo Levi | Shema | The importance of telling future generations |

| Hayim Gouri | Heritage | Jewish identity |

| Paul Celan | Psalm | God and man |

| Pavel Friedman | The Butterfly | A ghetto poem |

| Wisława Szymborska | Could Have | Fate and empathy |

| Dan Pagis | Written in Pencil in the Sealed Freightcar | Multiple themes |

| Martin Niemöller | First They Came for the Jews | Bystanders |

On the buttom of every poem you will find biographical details of each poet.

To view/print a PDF containing the biographical information of all seven authors.

You who live secure

In your warm houses,

Who return at evening to find

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider whether this is a man,

Who labors in the mud

Who knows no peace

Who fights for a crust of bread

Who dies at a yes or a no.

Consider whether this is a woman,

Without hair or name

With no more strength to remember

Eyes empty and womb cold

As a frog in winter.

Consider that this has been:

I commend these words to you.

Engrave them on your hearts

When you are in your house, when you walk on your way,

When you go to bed, when you rise.

Repeat them to your children.

Or may your house crumble,

Disease render you powerless,

Your offspring avert their faces from you.

Primo Levi: a Jewish-Italian poet and writer, was born in Turin in 1919. Before the Second World War he was an industrial chemist. In 1943 he was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where he survived due to his “usefulness” to the Nazis as a chemist. His most famous prose work is “If This is a Man” in which he wrote about his experiences in Auschwitz. Haunted by his Holocaust experiences, he committed suicide in 1987.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- Note the format of the poem. It has three sections with the ‘Holocaust’ description wedged between the comfort of a post-war description in the first verse and the severe admonition of the last verse.

- The last verse invokes a part of the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy (lines 3-6) and hence the title of the poem, Shema, which is also the first word of the prayer (translates as ‘listen’). Levi’s paraphrase of these 4 lines from the prayer are the background for his powerful admonition and warning to future generations to educate their children in the lessons to be learnt from the Holocaust. To see the prayer format in English and in Hebrew,

- The extremity of the threat in the concluding three lines written within a year of the poet’s liberation from Auschwitz-Birkenau, is some measure of the powerful emotions at play here - perhaps an expression of their need to transform their terrible experiences into something positive for future generations.

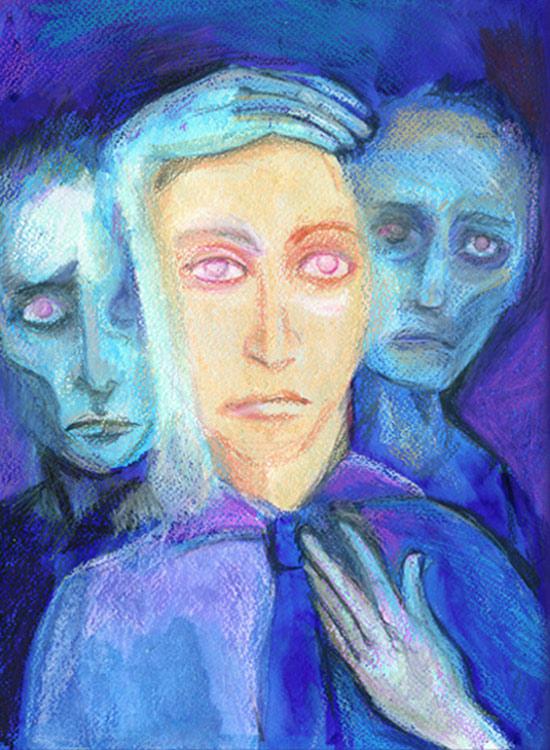

- The painting is filled with three images, two victims in the background and the generation after the Holocaust in the foreground. The future generations to whom the Holocaust has to be conveyed are not represented in the picture. The following points could be addressed:

- The quality of the victims’ eyes – sunken, pleading or admonishing as is Levi’s tone in the poem

- The figure up front receiving the victims ‘message’ has their hands on his heart and head and he demands full eye-contact with the viewer, thus fulfilling the generational contract at the heart of the poem

- The well-dressed figure in the foreground could correspond to those ‘living securely in their warm houses’ and the victims’ figures recall the second verse which depicts suffering of the Holocaust.

The ram came last of all. And Abraham

did not know that it came to answer the

boy's question- first of his strength

when his day was on the wane.

The old man raised his head.

Seeing that it was no dream and that the angel

stood there - the knife slipped from his hand.

The boy, released from his bonds,

saw his father's back.

Isaac, as the story goes, was not

sacrificed. He lived for many years,

saw what pleasure had to offer

until his eyesight dimmed.

But he bequeathed that hour to his offspring.

They are born with a knife in their hearts.

Hayim Gouri: a Hebrew poet, was born in Israel in 1923. He served in the Palmach, Haganah and Israeli Defense Forces, and after the Second World War was sent to Europe where he visited Displaced Persons’ Camps. His poetry covers a broad range of subjects, some intensely personal, reflecting his experiences during the Second World War and the Israeli War of Independence.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- This poem invokes the story of the sacrifice of Isaac from the Bible, Genesis, Chapter 22.

- The crux of the poem is arrived at in the last two lines of the poem. The question it raises for discussion is the legacy or ‘heritage’ handed down from this story to future generations. Are the offspring of Isaac encumbered forever with the scar of a perpetual wound (the knife) and /or is there a change in this perception in the Jewish world of today?

- The discussion should focus on the essence of Jewish identity in the present century after two millennia of Jewish history marked and scarred by the repeated pogroms and culminating in the Holocaust. The establishment of Israel in 1948 will naturally carry weight in the ensuing discussion.

- A parallel discussion can be generated on the universal application of the “Heritage” or the ‘perpetual wound’ (the knife) in terms of genocides around the world since the end of the Second World War.

- An additional theme that could be touched on is that of parental guilt in relationship to their children. This can be linked to the lines:

“The boy, released from his bonds,

saw his father’s back.”

The theme of guilt can be connected to accounts of Holocaust survivors who as parents, were powerless to protect their children. - The theme of parental guilt as seen in the line, “saw his father’s back” could be expanded to the ‘back’ or ‘silence’ of the surrounding bystanders who by allowing events to unfold were complicit in the tragedy of the Holocaust. The positive mirror image juxtaposed to the bystanders’ silent complicity is the bravery of the Righteous among the Nations who endangered themselves to save Jews.

- The artist’s conception of Gouri’s knife becomes a heavy globe borne on the back of the victim, grounds for further discussion in the classroom.

- Is persecution built into the human condition?

- Is ethnic violence endemic?

- Does the ‘globe’ represent a permanent weight to be borne by the majority of mankind?

- Is the painting an optimistic, pessimistic or realistic portrayal of Gouri’s main message?

- What is the artist portraying in the body-language of the victim?

Summary of possible points for discussion raised above:

- Jewish Identity after the Holocaust with the sacrifice of Isaac as a metaphor of the perpetual wound.

- Parental guilt.

- Genocides around the world since 1945 as universal scarring connected to the sacrifice of Isaac.

- Complicity of the silent majority –the bystanders.

- The moral alternative chosen by The Righteous among the Nations The last three points are tangential to the poem itself and are suggested here for teachers who wish to widen the historical canvass for their students.

Noone kneads us again from earth and loam,

noone evokes our dust.

Noone.

Praised be you, noone.

Because of you we wish

to bloom.

Against

you.

A nothing

were we, are we, will

we be, blossoming:

the nothing's-, the noonesrose.

With

its pistil soulbright,

its stamen heavencrazed,

its crown red

from the purpleword that we sang

over, o over

its thorn.

Paul Celan: Celan was born in Czernowitz, Bukovina in 1920. In 1942 Celan saw his parents deported to Auschwitz. He survived the Shoah in other camps but never recovered from his ordeal and in 1970 committed suicide. Celan’s highly acclaimed work is powerful, highly original, often ambiguous and deeply tragic.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- This poem was published in the last decade of Celan’s life when his poetry was becoming sparer and harder to penetrate. However the themes of the relative places of God and humankind and the relationship between them are clearly discernable.

- The title of the poem creates a further tension with the negations of God and humankind in the body of the poem. Psalms are normally paeans of praise. The opposite effect is created here and ample examples of the themes found in the text permit an interesting discussion.

- The negatives in the poem are paralleled in the last verse, which describes the rose and yet it concludes not with its beauty but with its exterior armor, “the thorn.”

- The artist’s portrayal of this poem is literal and confined to the rose and its thorns. The following are possible points for discussion:

- The relative place of the rose and its guardian thorns

- The shape of the rose – does it reflect the ambiguity of Celan’s “no one’s rose.”

- Consider the division of the painting created by the location of the rose in the corner and the thorns lying diagonally across the center.

The last, the very last,

So richly, brightly, dazzlingly yellow.

Perhaps if the sun's tears would sing

against a white stone. . . .

Such, such a yellow

Is carried lightly 'way up high.

It went away I'm sure because it wished to

kiss the world good-bye.

For seven weeks I've lived in here,

Penned up inside this ghetto.

But I have found what I love here.

The dandelions call to me

And the white chestnut branches in the court.

Only I never saw another butterfly.

That butterfly was the last one.

Butterflies don't live in here,

in the ghetto.

Pavel Friedman: Friedman was a young poet, who lived in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Little is know of the author, but he is presumed to have been 17 years old when he wrote “The Butterfly”. It was found amongst a hidden cache of children’s work recovered at the end of the Second World War. He was eventually deported to Auschwitz where he died on September 29, 1944.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- This poem was written in the Theresienstadt Ghetto and dated June 4, 1942. It was found together with other work done by children in the Ghetto all of which had been hidden from the eyes of the German perpetrators to be retrieved after the war.

- The poem alternates between positive and negative poles, between optimism and pessimism. Pavel was in his late teens when he wrote The Butterfly. Students his age can list the positive and negative descriptions in the poem.

- The young poet’s focus on the butterfly could be addressed in terms of its symbolic power in the context of life in the closed ghetto.

- The artist’s portrayal of this poem is very color-oriented. The contrast of dark and bright parallels the flights of optimism and pessimism in the poem.

- The following points could be discussed:

- The relative size of the butterfly

- The position of the butterfly at the edge of the page

In: Wislawa Szymborska, Poems: New and Collected, Harcourt, Orlando 1998, p. 111.

Wisława Szymborska: Szymborska was born in Poland in 1923, and lives in Krakow. Between the years 1945-1948 she studied Polish Literature and Sociology at the Jagiellonian University. Szymborska made her début in March 1945 with a poem "Szukam slowa" (I am Looking for a Word) in the daily "Dziennik Polski". She has worked as a poetry editor, a columnist and a translator. In 1996 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- Wisława Szymborska was one of the leading Polish poets after WWII and received the Nobel Prize in 1996. Sixteen years old at the outbreak of war, she internalizes the pain of the Nazis’ victims. The last two lines of the poem express her empathy.

- The poem is also an expression of the randomness of peoples’ fate in the Holocaust. The line in the second verse; ‘on the right. The left’, might be a reference to the randomness of the Selektion process carried out on the train-ramps outside of Auschwitz and Majdanek.

- The last verse also hints at the proportions of survivors and victims and the phrase… “one hole in the net…” points to the fact of a minority of survivors, like the one to whom the poem is addressed.

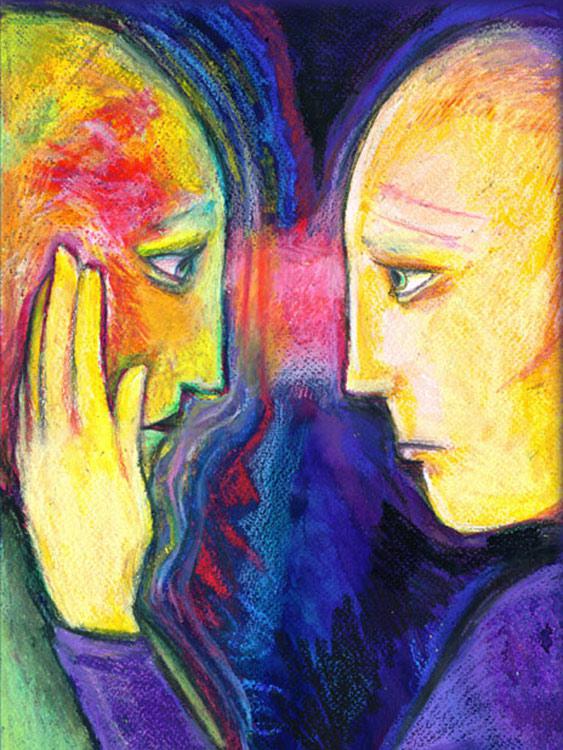

- The artwork linked to this poem invokes ‘The Other’ or the bystander in a graphic portrayal and begs to be discussed in terms of empathy and other emotions.

- Additional points to be noted:

- The intensity of the eye-contact

- The physical contact through an extended hand

- The sharing of suffering

Here in this carload

I am Eve

With my son Abel

If you see my older boy

Cain son of Adam

Tell him that I...

Dan Pagis: Pagis was Hebrew writer, born in Bukovina in 1930. His early years were spent in a concentration camp in the Ukraine from where he escaped. He settled in Israel in 1946 and taught medieval Hebrew literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He became one of the most vibrant voices in modern Israeli poetry. His references to the Holocaust are sometimes oblique and filtered through his use of biblical or mystical images. He died in 1986.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- In a very concise, concentrated poem of six short lines, Pagis succeeds in conveying much of the pain and terror of the Holocaust. The framework of the poem is the first universal family on earth and the heart of the poem is the request of the mother to convey a message to her one son that is left unformulated.

- Several themes emerge from the short lines of the poem; the case of the first murder in the history of mankind, the need to leave testimony, the place and role of mothers in the two tragedies of the first family and the Holocaust itself.

- Pagis only touches tangentially on Cain’s murder of his brother Abel and likewise, the context of the Holocaust appears only obliquely in the title. These ‘light’ touches serve to magnify the potential of the themes so elusively hinted at in the short poem.

- Pagis also creates a linear connection of man’s evil potential from the first murder to the multiple murder of the Holocaust by linking the story of Cain and Abel to the Holocaust through the title of the poem, which is in fact the only place where the Holocaust is alluded to.

- Pupils can consider if any one theme of the poem (see no. 2 above) was uppermost in the artist’s mind or perhaps they see expression of more than one theme in her painting.

- The artwork linked to this poem raises the question which “family” is being portrayed, Eve and Abel from the Bible or perhaps the mother and child in the Holocaust context.

First they came for the Jews

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for the Communists

and I did not speak out

because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the trade unionists

and I did not speak out

because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for me

and there was no one left

to speak out for me.

Martin Niemöller: Niemöller was a German pastor and theologian, born in Germany in 1892. Originally a supporter of Hitler’s policies, he eventually opposed them. He was arrested and eventually confined in the concentration Sachsenhausen and Dachau camps. He was liberated by the allies in 1945 and continued his career in Germany as a clergyman and as a noted pacifist.

Suggestions to the Teacher

- This poem, together with Szymborska’s Could Have, represents the bystanders in the human context of the Holocaust. Unlike Could Have, which highlights a bystander’s response after the Holocaust, Niemöller expresses contrition for his silence in the face of Nazi aggression when it applied in real time to other groupings.

- The message of the poem is that the perpetrators were permitted a free hand in their plans and faced no opposition when they arrested the different political and religious opponents of the regime.

- Historically, selected groups were not persecuted in the order presented in the poem. The weight of the war against Jews carried special moral significance for some clergymen and this is reflected in the order of the groups Niemöller presents.

- The painting linked to this poem invokes a timeless depiction of persecution.

The amorphous nature of violence and the dread of the threat are present in the painting. It is important to note that the focus of the painter gives prominence to the perpetrators and the viewer could feel himself as a potential victim. This angle is invaluable for creating an appreciation of the underdog.

- Primo Levi, Shema: Primo Levi, Collected Poems, Faber & Faber, p.9.

- Hayim Gouri, Heritage: Hilda Schiff (Ed.), Holocaust Poetry, St. Martin's Griffin, New York 1995, p. 5.

- Paul Celan, Psalm: Paul Celan, Selections, University of California Press, Berkeley/Los Angeles 2005, p. 78.

- Pavel Friedman, The Butterfly: I Never Saw Another Butterfly, Schocken Books Inc., 1994, p. 33.

- Wisława Szymborska, Could Have: Wislawa Szymborska, Poems: New and Collected, Harcourt, Orlando 1998, p. 111.

- Dan Pagis, Written in Pencil in the Sealed Freightcar [Translated by Stephen Mitchell]: Hilda Schiff (Ed.), Holocaust Poetry, St. Martin's Griffin, New York 1995, p. 180.

- Martin Niemöller, First They Came For The Jews: Hilda Schiff (Ed.), Holocaust Poetry, St. Martin's Griffin, New York 1995, p. 9.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders, but this has not been possible in all cases. If notified, Yad Vashem will rectify any omissions at the earliest opportunity.