A Teacher's Guide

Target Group: Students aged 15 and up

Suggested Time: Two class periods (90 minutes)

Rationale:

Rationale:The educational concept of Yad Vashem places a focus on the victims. Students should be encouraged to learn more about European Jews and how they lived before Nazi Germany and their accomplices persecuted, humiliated, dehumanized and ultimately killed them. In order to foster the students’ empathy for the victims, it is important take a closer look at Jewish individuals, presenting them as living human beings with hopes, traditions, and dilemmas.

This lesson plan aims to introduce the lives of Polish Jews in the interwar period. It presents Poland's Jews through their dreams, politics, religious beliefs, education, youth movements, sports and leisure activities in order to dismantle stereotypes and to deepen the students' acquaintance with the tapestry of Jewish-Polish life. The Jews in Poland, who constituted approximately 10% of the general interwar Polish population, participated in all fields of life and left an imprint on Poland in a way that remains until today.

Materials for preparation:

Materials for preparation:Worksheets with short biographies of selected Jewish characters, to be printed (and preferably laminated)

Photos, to be printed and affixed to the wall throughout the classroom, in a maximal size (at least A4)

Glossary, copied to be distributed to the students

Procedures:

Note to the teacher:

Make sure that this is not the students’ first encounter with the topics of Judaism and Jewish people; otherwise, the unfamiliar terminology and concepts may overwhelm them.

I. Introduction: Facets of Jewish Life in Poland between the World Wars

I. Introduction: Facets of Jewish Life in Poland between the World WarsSuggested time: approximately 20 minutes

Start the lesson by letting the students walk through the room, examine the photos affixed to the wall, and gather impressions:

Imagine that you are walking in Poland ninety years back in time. What do you see in the Jewish-Polish streets? What catches your eye? What surprises you? How can you characterize Jewish life (you may relate to religion, politics, languages, and leisure activities)?

Note to the teacher:

This stage serves as a preparation for the next one. It is very important to ask each question separately, give sufficient time for the students to answer the questions, and add more information where necessary. A wide range of information may be obtained:

Religion:

Approximately more than a third of Polish Jews were religious in the interwar period. Those who identified clearly as Jews were Orthodox Jewish people. They observed Halacha (Jewish law) and were less interested in integrating into the local population.

There were also modern Orthodox Jews. They stood out less, since they were religiously observant but dressed like the non-Jewish majority. There were also traditional Jews, meaning they kept traditions of Judaism like Friday evening Sabbath rituals, gathering the whole family together, or attending the High Holidays.

There was no Reform Judaism in Poland in the interwar period, but there were Jews who were more liberal: they kept the rules for observing the Sabbath less strictly, sermons in synagogue would be delivered in Polish, but they didn't change the fundamental concept of observance like the German-rooted Reform Movement did. An example of that is the Tłomackie Synagogue in Warsaw

Language:

Languages can often reveal aspects about the sense of belonging and the (felt) national, and even political, identity of people. In a Jewish-Polish Street several languages could be heard: Yiddish, Polish and Hebrew. According to data collected in Poland in 1931 regarding mother tongue, 80% stated Yiddish as their mother tongue, 12% Polish and only 8% stated Hebrew

Politics:

By discussing the wide spectrum of Jewish political parties, students can learn about the great diversity in Jewish society. Their platforms and viewpoints also reflect how Jews related to Poles. From this prism, one can see the change the Jewish society underwent during the 20th century. It shifted from a traditional society to modernity, confronting its changes.

Polish Jews during the interwar period can be divided into three political blocs:

- Approximately 40% voted for the Bund (General Jewish Workers' Union in Lithuania, Poland and Russia), a secular, socialist Jewish party that was established in 1897. The majority of Polish Jews were workers, even if they were religious. Overall, their daily concerns and struggle to earn a living were the most important issues to them, and so they tended to vote for those who would safeguard their rights. The Bund focused on the struggle of the proletariat, ensuring the rights of Jewish laborers, seeking to protect Jews from pogroms, and organizing political strikes against antisemitic policies. The Bund was a secular movement that struggled against the Jewish religion. It also vigorously opposed Zionism, as well as the Hebrew language and its culture, calling for Yiddish to be the national language of Jewish people in Eastern Europe. The Bund aspired to secure equal rights for Jews in a democratic socialist state in which the Jewish people could enjoy cultural autonomy. Before the war, the Bund was active in all areas of Jewish public life, including politics, education and culture, and was known for its resolute fight against antisemitism in Poland in the late 1930s.

- Around 30% identified with the Zionist parties (the whole spectrum - from right-wing revisionists to the most left-wing socialist Zionists). This bloc emphasized the future of Europe's Jews in Zion, in Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel)

3 . Jewish nationality, the Hebrew language and Jewish history were very important to them. Since the majority of Polish Jews were poor and did not have the financial means to immigrate to the Land of Israel, they felt the need to invest practically in their present lives in Poland to ensure a stable living standard until their dream of a life in Eretz Yisrael became feasible. - Around 30% supported Agudat Yisrael. This was a worldwide association of Haredi (strictly Orthodox) Jews, founded in Katowice in 1912. Agudat Yisrael regarded the Torah and Jewish tradition as the basis for the eternal existence of the Jewish people. The organization tried to form a united front against the penetration of secular ideas into Jewish life. Agudat Yisrael was highly successful in the educational and social realms and became the political entity representing Orthodox Jewry vis-à-vis the authorities.

One of the great achievements of Agudat Yisrael was the establishment of Beit Yaakov, a Haredi girls' school founded in Poland in 1917, which developed into an educational network with schools all over the world. Until Beit Yaakov was established, girls from strictly religious families either studied at home or attended general Polish schools. As the secularization process intensified and the demand for general education increased, it became clearer that an educational establishment suitable for Orthodox Jews in Poland was needed. The first school was founded in Krakow by Sarah Schenirer with the support of the leaders of Agudat Yisrael. Within a few years it became a widespread educational network with a teachers' college and over fifty schools.

Leisure:

Like people today, Jews went out to coffeehouses, performances, youth movements, sporting events etc. More than half a million people visited the Jewish theater in Warsaw in 1935. However, the theater was not equally accepted by all. For example, those who tended to an assimilated life style opposed it since there was a Polish theater. After all, why should the Jews have a separate one? Likewise, the Orthodox opposed it since in their view, it was non-Jewish culture.

For detailed information about the history of Poland's Jews before the Holocaust, it is recommended to consult the YIVO Institute's website

- Tłomackie Synagogue: The Great Synagogue was built by the Jewish community of Warsaw between 1875-1878 at Tłomackie Street, in the south-eastern tip of the district in which Jews were allowed to settle by the Russian imperial authorities. After the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, on 16 May 1943, the SS blew up the building. It was not rebuilt after the war.

- Cf. Mendelsohn, Ezra (1987). The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars. Indiana University Press. pp. 30–31.

- The term Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel) refers to the biblical homeland of the Jewish people and is not defined by clear-cut borders. It should not be confused with the modern State of Israel in its contemporary borders.

- Józef Klemens Piłsudski (1867–1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (1918–22). He was considered the de facto leader (1926–35) of the Second Polish Republic. Piłsudski believed in a multi-ethnic Poland, "a home of nations", including ethnic and religious minorities that he hoped would establish a robust union with the independent states of Lithuania and Ukraine.

- Hasidism is a sub-group within Haredi Judaism. Its members closely follow both Orthodox Jewish practice – with the movement's own unique emphases – and the traditions of Eastern European Jews.

II. Focusing on the Individual

II. Focusing on the IndividualSuggested time: approximately 25 minutes

Hand out the biographical sheets (depending on the number of students, hand out one biography to one or two students), as well as the glossary to every student/pair. Distribute nametags to the students and invite them to write their character's name on it and wear it.

Ask them to read the biography and invite them to assume, for the duration of this exercise, the identity of the narrator in this text. Ask them to study the everyday life of their character: Which languages did he/she know? Did he/she attend synagogue? Where did he/she study? What was his/her profession? What did he/she do for leisure? How did he/she feel about Poland? About Eretz Yisrael? Where did he/she see their future?

Note to the teacher:

Role-playing is problematic in Holocaust education, since it demands from students to a certain degree to identify with "their" character. We thereby suggest to avoid simulations that encourage students to identify with perpetrators or victims. However, since this activity focuses on pre-war life, role-playing is used in an effort to revive the Polish-Jewish world in an inspiring, hands-on learning activity. It is recommended to ask the students to remove their nametags at the end of this activity.

Before the concluding discussion, we suggest presenting the later fate of the individuals as they lived through the years of persecution.

III. Composing the Full Picture: The Individual as Part of a Multi-Faceted Society

III. Composing the Full Picture: The Individual as Part of a Multi-Faceted SocietySuggested time: approximately 25 minutes

During the following moderated discussion, the students will analyze the individual biographies. With the help of specific questions, the students examine the way of life of each character: his/her political affiliation, religious beliefs and social activities, attitudes and positions. The student should answer the questions in the first person, assuming temporarily the identity of his/her protagonist. In order to trigger a dynamic and vibrant discussion, it is important for the teacher to be familiar with the uniqueness of each character and his/her background.

Sample questions:

- Who here speaks fluent Hebrew?

- Who speaks fluent Polish?

- Do you attend the synagogue on a daily basis?

- The opera is in town. Will you go?

- Maccabi (a Jewish team) and Krakowia (a Polish team) are scheduled to play a football match. Will you go? Whom will you support?

- Piłsudski

4 passed away. Will you attend his funeral? - It is 1936 and a pogrom has taken place in Przytyk. What is your response? How and where do you foresee your future?

- Your cousin has sent you a visa to the USA. Will you go?

Summary of the biographies:

- Roman Frister: His father served in Piłsudski's regiments in World War I. Frister was ten years old at the outbreak of World War II. He went to the Hebrew School (mostly in Polish).

- Rabbi Dovid Bornsztain of Sochaczew: Chasidic

5 Rebbe. He bought land in Eretz Yisrael for a religious settlement. - Ester: Studied and later taught at Beit Yaakov. Very interested in Polish literature and culture. Won first place in an essay contest on behalf of Piłsudski.

- Ciwja Lubetkin: A Zionist from a traditional family, but she herself did not practice traditional Judaism. When the World Jewish Congress was founded in Geneva (Switzerland) in 1936, she served as a representative from Poland.

- Julian Tuwim: The famous pianist Artur Rubinstein was his uncle, so he had free entrance to the opera.

- Urke Nachalnik: He was the head of the Jewish Mafia, a thief.

- Yurek: He had three names: Israel-Chaim, given to him by his parents; Aryeh (Lion), by the socialist-Zionist youth movement Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa‘ir; and Yurek, a Polish name.

- Ludwik Hirszfeld: He converted to Catholicism. Since the Nazis defined a person biologically as Jewish when three out of four grandparents were Jewish, they did not accept conversion of Jews as an act that would change their racial definition. Although he is included in this workshop, he would not have perceived himself as Jewish.

- Abrasha (Abraham) Blum: He was raised in a traditional home and studied in a religious boy school (Cheder). Became politically active and joined the youth movement of the Bund (Tsukunft). Later he became a leader of the Bund Jewish-Socialist Party.

- Marek Edelman: He grew up in a secular, socialist home, both parents being active Bund members. As a teenager, he joined the Bund's youth movement (Tsukunft).

IV. Conclusion

IV. ConclusionSuggested time: approximately 10 minutes

Following this discussion, it is recommended to summarize the different streams of Jewish life in Poland before World War II, and the fact that the identity of a person can never be defined solely through external attributions or memberships. It is rather important to take into account the way how people perceive themselves.

Formally conclude the discussion by removing the names tags that the students attached to themselves at the beginning.

The workshop ends with some information about the fate of each of the discussed characters during and after the war:

- Roman Frister: Survived Krakow ghetto, Płaszów, Auschwitz-Birkenau and other camps. Was sixteen years old at liberation and became a journalist. He immigrated to Israel in 1957, following an outbreak of antisemitism. A journalist in Israel, he established the prestigious Koteret school for journalism. Wrote for the newspaper Haaretz and had a weekly column in Polityka. Passed away in 2015.

- Rabbi Dovid Bornsztain of Sochaczew: Even though he owned land in Eretz Yisrael, he remained with his congregation. He died in the Warsaw ghetto.

- Ester: All of the information about this person is based on the essay contest in the interwar period where she took part.

- Ciwja Lubetkin: Took part in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. She escaped from the ghetto through the sewers to reach the Polish side. Participated also in the Warsaw Uprising of the Polish underground in 1944. Immigrated to Eretz Yisrael in 1946, married Antek Cukerman and was among the founders of the Ghetto Fighters' Kibbutz. Her granddaughter was the first female pilot in the Israel Defense Forces.

- Julian Tuwim: Escaped in 1940 to the USA. Wrote in 1944 the essay "We are the Polish Jews." Returned to Poland after the war and died there in 1953.

- Urke Nachalnik: Served time in prison, was pardoned and changed his ways. Wrote and published his life’s story. Perished in the Otwock ghetto.

- Yurek: Became a courier of the Jewish underground movement during the war, including information about the “Final Solution” to Warsaw. He was caught while acquiring weapons for the underground and tortured by the Gestapo. The underground managed to pay a bribe for his release. During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, he was exposed at the main bunker in Mila Street 18 and committed suicide in order to avoid falling into the Germans’ hands.

- Ludwik Hirszfeld: Confined in the Warsaw ghetto with his wife and daughter, he tried to aid the residents there. Survived in hiding, and later immigrated to the USA.

- Abrasha (Abraham) Blum: He was confined in the Warsaw Ghetto, where he continued engaging in social and political activities. He became a member of the Jewish underground movement and fought in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Blum then managed to escape the ghetto through the city's sewers and hid in the forest for several days; he then returned to Warsaw and went into hiding. When he was discovered, he tried to escape from the fourth floor of a building by tying sheets together and sliding down. However, the sheets tore, and Blum was injured and captured by the Germans. He was taken to the Gestapo, and was never heard from again.

- Marek Edelman: When the Nazis occupied Poland, he was confined in the Warsaw Ghetto. He joined the ghetto's Jewish Fighting Organization and became one of the commanders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. He survived and chose to stay in Poland after the war. He became a cardiologist. During the early 1980s, he was active in Lech Walesa's Solidarity Trade Union Movement.

Glossary

GlossaryAGUDAT ISRAEL:

A worldwide association of haredi (strictly orthodox) Jews, founded in Kattowitz, in 1912. Agudat Israel regarded the Torah and Jewish tradition as the basis for the eternal existence of the Jewish people. The initiative to found the organization came from the Freie Vereinigung fuer die Interessen des orthodoxen Judentums (Free Union for the Affairs of Orthodox Jewry), which for years had attempted to unify Orthodox Jewry and for a united front against the penetration of secular ideas into Jewish life. Agudat Israel was highly successful in the educational and social realms and became the political entity representing Orthodox Jewry vis-à-vis the authorities. Until World War II, Agudat Israel was opposed to Zionism, but the changes in the situation of the Jewish people- mainly due to World War II and the Holocaust- caused it to modify its path. Today it is a haredi political party in Israel.

BEIT YA’AKOV:

Haredi (strictly orthodox) girls’ school founded in Poland in 1917, which developed into an educational network with schools all over the world. Until Beit Ya’akov was established, girls from haredi homes either studied at home or attended general Polish schools. As the secularization process intensified and the demand for general education increased, it became clearer that an educational establishment suitable for the support of the leaders of Agudat Israel; within a few years it became a widespread educational network with a teachers’ college (established 1922) and over fifty schools.

BETAR:

Hebrew acronym for Berit Yosef Trumpeldor (Joseph Trumpeldor Alliance), a youth movement founded in Riga in 1923 by Aharon Propes. Conceived as a small-scale local organization, during its early years Betar’s ideological platform was somewhat vague, concerned chiefly with reviving the idea of the Jewish legions that had operated during World War I. After a few years, Betar developed a more concise ideology, becoming the official youth movement of Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Union of Zionist Revisionists, which itself only came into being in 1925. Betar was confined mainly to Eastern Europe, with branches in Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, and other countries, first and foremost Poland, which, in 1928, succeeded Latvia as host to the organization’s headquarters. From Poland, Betar spread to other countries and opened its first branches in Palestine.

BUND:

Shortened for of Algemeyner Yidisher Arbeter Bund in Lite, Poyln un Rusland (in Yiddish) General Jewish Worker’s Union in Lithuania, Poland and Russia. A secular socialist Jewish national movement founded in Vilnius in the late nineteenth century. On the eve of World War II it was the largest Jewish political party in Poland. The Bund devoted most of its time to economic struggle and to ensuring the rights of Jewish laborers, as well as working energetically to protect Jews from pogroms and organizing political strikes against anti-Semitic policies, the Bund was a secular movement that struggled against the Jewish religion. It also vigorously opposed Zionism, as well as the Hebrew language and its culture, calling for Yiddish to be the national language of the Jewish people in Eastern Europe. The Bund aspired to secure equal rights for Jews in a democratic socialist state in which the Jewish people could enjoy education, and culture, and was known for its determined fight against antisemitism in Poland in the late 1930s. During the war, the Bund was one of the mainstays of Jewish underground activity.

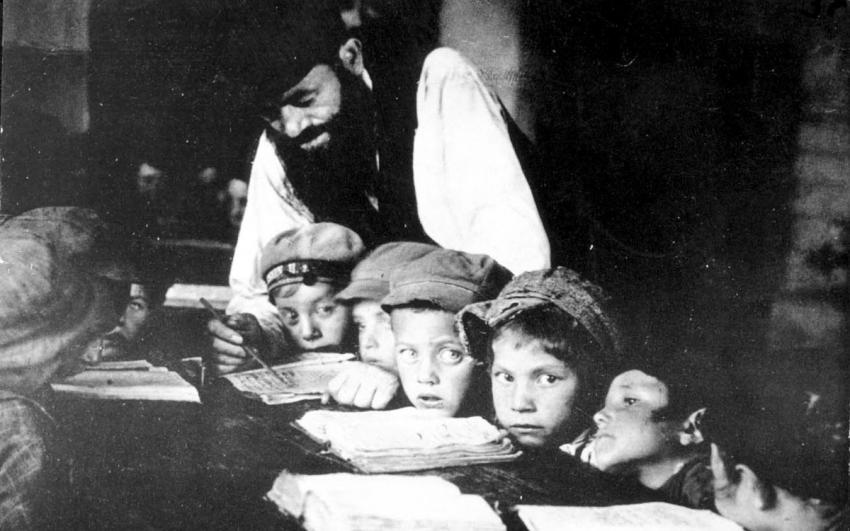

CHEDER:

(Heb. cḥeder; lit. “room”), the most widely accepted and widespread elementary educational framework among East European Jewry since the Middle Ages. Study in a cheder was considered an integral part of the process of raising and socializing a Jewish child, including the inculcation of Jewish religious and cultural values through imparting basic knowledge of the canonical sources (Torah, Mishnah, Talmud) and of the liturgy. Pupils spent the entire day in cheder, beginning with morning prayers, followed by study of various subjects, and ending with evening prayers. (In certain areas it was customary to give pupils a midday break of one or two hours.) Both boys and girls studied in many cheders, either together or separately. There were no criteria for acceptance to cheder, and no consideration was given to disparities in the intellectual and cognitive abilities of the students.

TSUKUNFT:

Founded in 1913, Yugnt-Bund Tsukunft (the Future) was the main Bundist youth organization in interwar Poland.

DROR:

The name of two different youth organizations, disconnected geographically, but related to each other ideologically and politically. The term dror means “freedom.” The Zionist Socialist Federation “Dror” originated in Kiev, where a group of Jewish youth began to evolve into an organization on the eve of World War I. While trying to preserve its unified organizational structure in a new environment, Dror actually followed two paths: a group led by David Lifshits acted as a political party, one that failed in every aspect of its endeavors. Dror’s other focus was on education, and the arena of its efforts in this facet was the He-Ḥaluts organization. The Polish He-Ḥaluts was an administrative institution that organized immigration of Jewish youth to Palestine. It had neither a particular ideology nor educational or preparatory institutions in Poland. Dror’s members, led by Aharon Berdichevski, held national and regional posts and cast He-Ḥaluts according to their vision, implementing an educational system with a clear-cut outlook.

FRAYHAYT:

The youth organization Frayhayt (Freedom) was founded in the summer of 1926; it had an eclectic socialist Zionist ideology that focused primarily on political and professional activities in the Jewish communities and on the socialist education of its members. It differed from other Zionist youth movements in its social composition: 85 percent of its members were working youth. For this reason, perhaps, Frayhayt supported the Yiddish school system. Although Frayhayt viewed itself as a movement of adolescents, the pressure of younger age groups compelled it to change its structure and to build an educational stratum of scouts. Internal ideological developments, along with severe unemployment, shifted the focus of Frayhayt’s activities to preparing its members for the pioneering kibbutzim. At the second conference of the movement in May 1931, it declared itself an integral part of He-Ḥaluts, with the goal of preparing its members to join the kibbutzim of Ha-Kibuts ha-Me’uḥad.

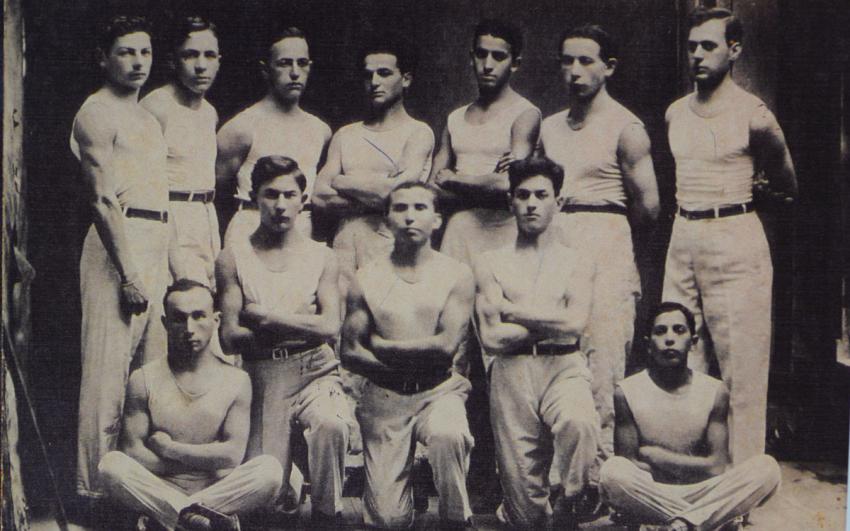

HA-POEL:

The Jewish Socialist Zionist Workers Sports Federation. Ha-Po‘el (“the Worker”) sports clubs were established at a conference in Tel Aviv on 15 May 1926, under the aegis of the Histadrut labor union. The Ha-Po‘el federation considered itself part of the organized socialist workers’ movement and, by 1927, had joined the Socialist Workers Sports International (SWSI). The federation soon set up Ha-Po‘el organizations in Eastern Europe.

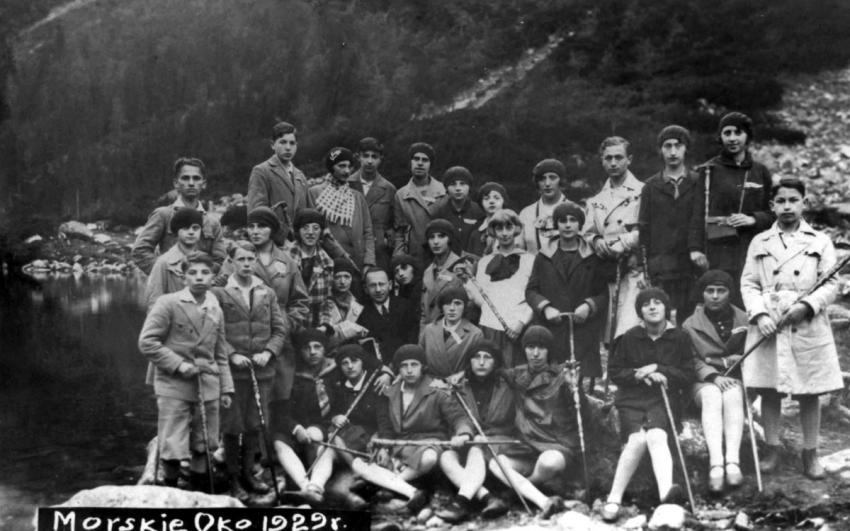

HA-SHOMER HA-TS’AIR:

Zionist socialist youth movement. Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa‘ir (The Young Guard) educated and trained its members for immigration to a kibbutz in Palestine. The movement originated in Galicia—at that time a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—a result of the merger of Tse‘ire Agudat Tsiyon, which was involved in the teaching of Hebrew, Judaism, and Jewish history, with Ha-Shomer, an amalgamation of scouting organizations that considered the distinct Palestine Ha-Shomer organization a worthy model to emulate. In 1916, at a meeting of Galician refugees from World War I in Vienna, the two groups officially united to form Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa‘ir.

HE-HALUTS:

Zionist pioneering movement. Local pioneering groups had been founded from the earliest days of Zionist settlement activity during the First and Second Aliyahs (1882–1903; 1904–1914). However, larger regional and national frameworks appeared only from 1917 onward, the year of the Balfour Declaration, the Russian Revolution, and the emergence of newly established states in Eastern Europe. The founders of He-Ḥaluts believed that no political or propaganda accomplishment would benefit Zionism in the long run unless it were complemented by deeds of personal fulfillment, which became a primary objective in the organization’s overall ideology. In other words, to actually implement the principles of He-Ḥaluts, the individual was expected both to identify with the Histadrut (Labor Federation) and to live on a cooperative kibbutz in Palestine.

YESHIVA:

The yeshiva in Eastern Europe in the early modern period trained young men to study formative texts and traditions, especially the Babylonian Talmud, the commentaries on it, and the legal decisions that depended on it. By the nineteenth century, the term yeshiva describes a traditional East European Jewish locale for full-time advanced study of Talmud by youths and young men.

MACCABI:

Zionist gymnastics and sports organization. The establishment at the end of the nineteenth century of a national Jewish gymnastic society in Europe can be explained as a reaction to mounting nationalism across the continent, with concomitant exclusion of minorities and heightened antisemitism. The Maccabi federation of Poland was the strongest pillar of the World Union. In the 1930s, its membership included 30,000 Jewish athletes in 250 clubs. The Polish model demonstrated perfectly the Zionist orientation of the Maccabi movement and the competitive sporting dimension of “muscular Jewry.” Ideologically and financially, Maccabi societies in Poland encouraged emigration and the promotion of the Jewish community in Palestine. Maccabi athletes competed in Polish national championships in all of the classic disciplines. Jewish athletes set records in boxing, wrestling, and weightlifting—disciplines that held particular symbolic value for developing “muscular Jewry,” and contradicted the stereotype, once deplored by Nordau, of Jews as weaklings.

MIZRAHI:

Orthodox Zionist movement whose name was derived from the words “the Land of Israel for the People of Israel according to the Torah of Israel.” The movement advocated the realization of the Zionist vision and incorporated some of its modern and revolutionary characteristics.

PO’ALE TSIYON:

In the early twentieth century, the Labor Zionist Po‘ale Tsiyon (Workers of Zion) organization evolved from various groups in Eastern Europe. Seeking to base Zionism on the Jewish proletariat, the Po‘ale Tsiyon rejected territorialism, Bundism, and assimilationist Marxism as solutions to the Jewish Question. Straddling the boundaries of revolutionary socialism and Jewish nationalism, the movement then experienced a large number of splits and disagreements over such issues as Palestine versus the Diaspora, Hebrew versus Yiddish, cooperation with non-proletarian Zionists, support for the USSR, and others.

TALMUD-TORAH:

Orphans, or children of poor families who were unable to pay the normal tuition fees, studied in a Talmud Torah, and most communities had a Talmud Torah society that was responsible for raising funds to run this institution, to hire teachers, and even to test the students.

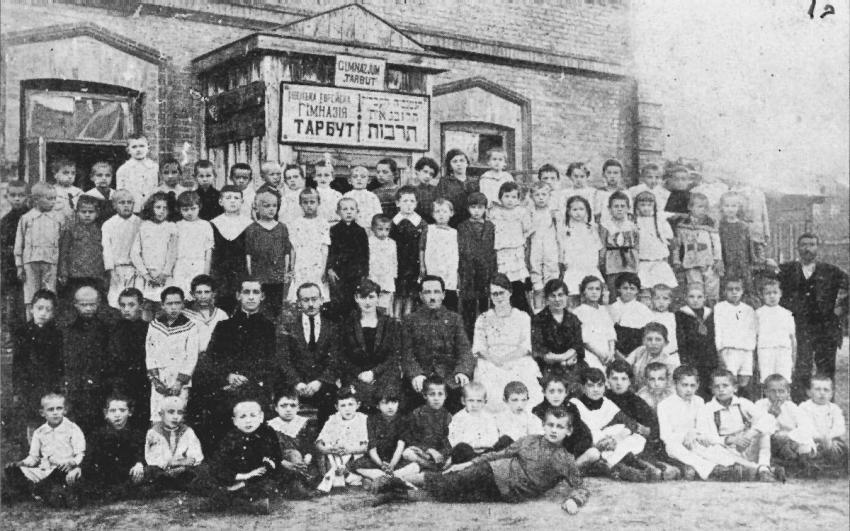

TARBUT:

A network of secular Zionist educational institutions that functioned in Poland in the interwar period; the language of instruction was Hebrew. The network operated kindergartens, elementary schools, high schools, teachers’ seminaries, and agricultural schools. Additionally, it provided pedagogical courses, evening classes for adults, and lending libraries; and published pedagogical journals, educational textbooks, and children’s journals.

YOUTH MOVEMENTS:

Jewish youth movements in Eastern Europe, particularly in the interwar period, achieved extraordinary strength, numbers, and influence as a result of a number of interrelated contemporaneous factors, in addition to the particularly pressured conditions under which, for example, all of Polish Jewry lived. The Jewish youth movements in interwar Poland may be placed into four main categories based on ideology. The first included Zionists of various stripes. A second category consisted of cultural autonomists and holders of similar outlooks, a third group was made of Communists; and a fourth of assimilationists, some of whose leaders believed that Jews should obtain full civil rights in Poland without forfeiting identity and ethnic solidarity.

Sources:

Tessler, Rudolph and Edith, Years Wherein We Have Seen Evil. Selected Aspects in the History of Religious Jewry During the Holocaust, Yad Vashem, 2003, vol. I-IV.

Biographies

BiographiesUrke Nachalnik

My name is Urke Nachalnik. Actually, that is my nickname. In Yiddish, “Urke” means “thief,” and Nachalnik is the nickname that stuck to me while I was in prison. I will tell you briefly how I became a thief, and how they caught me and put me in jail, though it is a long story.

I was born in a small town, called a “shtetl” in Yiddish, a small town in the area of the Narew River. My mother came from a Hasidic family, and the home where I grew up was traditional. My father was a miller, many of the Jewish townspeople worked in those types of jobs: baker, butcher, carpenter, tailor and miller. In my childhood, I went to “Cheder,” a religious elementary school, where they taught in Yiddish and Hebrew. I was a very good student, so after my Bar Mitzvah, my parents decided to send me to continue my studies in a larger yeshiva (Talmudic college). I was sent to study in the city of Lumza, and I found myself, a young teenaged yeshiva student in a big city. Not that Lumza was so big, but everything is relative, and compared to our small town, it was a very large city. A local Jewish family took in every student that came to study at the yeshiva. A couple, a 70 year-old Jewish man and his wife, who was 40 years younger than him, took me in. They had no children. I, as you understand, was a rebel by nature, and the temptations in the big city and in the home where I stayed were great, so you already understand…

Towards the end of my studies, my mother died. I had to return to the small town and help my father in his work. Father would send me to collect money from a customer. It used to be standard for customers to buy with credit, and every so often the money had to be collected. Once I went to collect money and never returned; that is, I took the money and began wandering. I arrived in Vilnius, which was a Jewish center, called “the Jerusalem of Lithuania,” where I worked as a private Hebrew teacher for a wealthy Jewish family. But I “collected” a bit of money from that family too, which forced me to keep wandering…But in the end, all thieves get caught. I was caught and sent to a Russian prison. That was in 1913. In the Russian prison, I met all types of thieves, and I really broadened my horizons. At the end of my prison term, I was released and joined a group of thieves, which was actually a gang of burglars.

From a young adolescent who grew up in a small Jewish town, studied Jewish and biblical literature, and had a bright future in the rabbinical world to look forward to, I became a renowned thief. The course of my life took me many places, including capital cities such as Warsaw and Berlin. I learned to escape from place to place without leaving any tracks; I was one of the quickest pickpockets. My life included love affairs with many women. Over the years, my career began to decline, but nobody would forget that I was one of the heads of the Jewish mafia in Poland. That is enough for now, there is much more to tell, but I have to run.

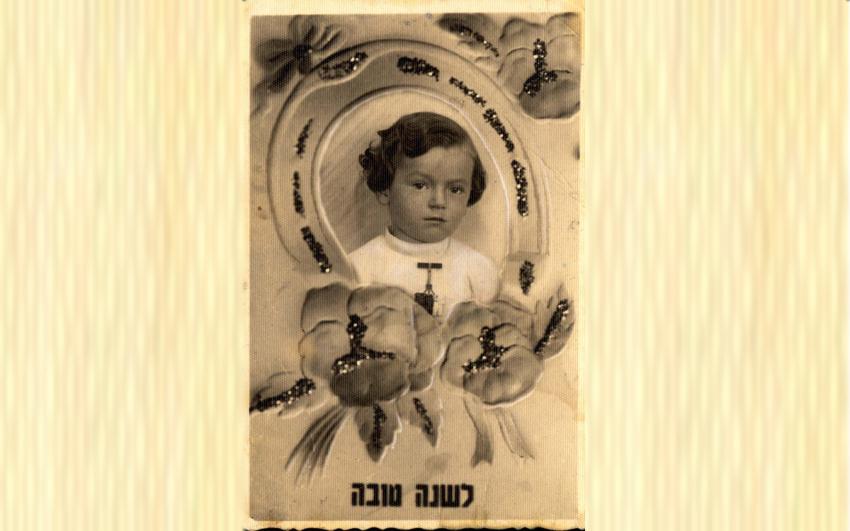

Ester

My name is Ester. I was born in 1920 to a Hasidic family. My father was from the Gur Hasidic sect. When I was five years old, my father brought home a “melamed,” or teacher, but I don’t remember much of what he taught me. At the same time new rumors began to spread about a woman named Sarah Schenirer, who was about to open a school for religious girls. Just thinking about a school was like thinking about magic. I had so many questions… First I thought: what would such a place look like? I imagined rows and rows of benches. Afterwards I would imagine the teacher – she would be tall and large. Just think of it, going to school! For me it was a dream. I wondered what we would learn. Father would say, “First you will learn how to pray, and to write in Yiddish of course, and then you will learn the prayers.” When he told me that we would study the five books of Moses, I held my breath and asked if we would also study the commentaries and Talmud. His answer was, “Girls don’t study Talmud.”

After two years at the Beit Ya'akov religious girls’ school, I very much wanted to study in a Polish public school, as did many of my friends. At home, we almost never discussed the option of studying in a school whose language of instruction was Polish! And boys and girls learning together! It took me a long time, but I quietly and humbly managed to convince my father to let me go to the Polish school as well. All that time I continued to study at the Beit Yaakov religious girls’ school. In the Polish school, I met teachers who were irreligious Jews and who spoke only Polish. I would have to learn Polish – you see, at home we only spoke Yiddish. In school there was a library, and though Father did not want me to read books in Polish, I managed to convince him to allow me to, and I enjoyed every story and every tale.

Though I studied in the Beit Ya'akov religious girls’ school and in public school, I also went to a youth movement called “Batya,” a youth movement for Charedi (strictly Orthodox) girls. It was established by Sarah Schenirer (how could it not?) and it belonged to the Agudat Yisrael party. My life was so full of activities that I forgot what was going on at home. Our store was small, and father was looking for additional sources of income, so he also became a “melamed” for boys. The economic crisis was very painful.

When I was in 10th grade, father had to sell his store for good; he just could no longer maintain it. The situation at home became more and more difficult. I, on the other hand, was very successful in school. Twice I spoke in honor of Marshal Jozef Pilsudski and the mayor, who was present, offered to help me. The help I needed, of course, was money. In order to continue to study in high school, I had to pay tuition, which was almost impossible in our household. My father, on the other hand, wanted more than anything for me to study in the Beit Yaakov seminary in Krakow; he was willing to work double for that, and he did. To my great sorrow, father died young. He was 49. I did not go to study in Krakow, but I found work as a teacher in a Beit Ya'akov school in a small town. I have many grievances regarding the system in which I grew up. I loved Polish literature, and Polish writing and language excited me. I wanted to read and read, and write, so I kept a diary. I had a good friend who left Beit Ya'akov school in the middle of her studies, and my parents did not want me to meet her because they were afraid that she would steer me off the right path. At the same time, I decided that I could teach reading and writing, the five books of Moses, and thus develop the desire to learn, and curiosity in general, among my students. That is how I became a very young teacher in Beit Ya'akov.

Civia

My name is Civia Lubetkin. I was born in a very Jewish town called Byteń, located in eastern Poland in one of Polish regions on the banks of the Shchara River. I was born on 9 November 1914, and my parents were named Yakov Yitzchak and Chaya. We were six children, five girls and one boy. My father was a merchant, a grocery store owner, and our family was middle class.

My sister, my brother and I went to a Polish public elementary school. My brother was later sent to a yeshiva (Talmudic college) in Vilnius, and then for higher education to Warsaw. My father was a religious man and our home life followed Jewish tradition. Aside from our public schooling, my sister and I were sent to a private Jewish teacher nicknamed “Berel the Melamed” (Berel the tutor), where groups of us studied Hebrew, the five books of Moses and other subjects related to Jewish thought and philosophy. So when I went to “hachshara” (a communal Zionist agricultural training program), I already knew Hebrew. I only had to improve my everyday language, since in cheder (religious elementary school) we learned the holy language. At home we spoke Yiddish, and in practice we spoke three languages: Polish in school, Hebrew in the girls’ cheder, and Yiddish at home. My father made the highest and final decisions at home and he was certainly more religious and stricter than mother, who tended to turn a blind eye, for example if she saw us riding a bicycle on the Sabbath.

The political situation at home was diverse. Father was a Mizrahi (religious Zionist political party) follower, and mother had Revisionist (right-wing Zionist movement) tendencies, while from an early age my sister Bonia and I were members in the youth movement Frayhayt, which later became Dror (“Freedom”- left-wing Zionist youth movement). Our movement was associated politically with Poalei Zion (“Workers of Zion”- left-wing Zionist party), and to the umbrella organization Hechalutz (“The Pioneer”).

I believed with all my heart in the potential of Zionism and socialist fulfillment, and I was ready to give my life for that goal. It was very difficult to convince my parents to let me go to hachshara. There were Jewish families who would taunt, “What, is there nothing to eat at home, so you send your daughter to hachshara?” You have to remember that for girls, it was more difficult to leave the home. My parents were afraid that I would be exposed to bad influences, where boys and girls lived together, go out to work for the Poles, etc. Father fiercely objected – I did not argue with him, but I remained strong in my convictions. He said “no,” and I kept saying “yes!” In the end, of course I went to the hachshara in the city of Lutzk. Youth movement life was my life from a very young age – in the movement we would read books and discuss and debate them for hours! We traveled the length and breadth of Poland, put on plays, learned about Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel) and the lifestyle we would live there, the new social Zionism. I remember that once I came home to visit, I was wearing simple clothes with a leather jacket (that was the style for boys and girls in hachshara) and I described my work in the bakery, in the laundry, in the lavatories, etc. I told how I got on the train without buying a ticket; father looked aghast, so did mother, and I understood that I was breaking away from them. The break was sad, but I was thrilled with the opportunity to be part of the new world in Eretz Yisrael.

As an active member of the movement, I went to many central locations for hachshara. It turns out that I was good at working in education and training, because I was called to work in the main branches of Hechalutz, the umbrella organization of the agricultural training communities, and I was appointed the coordinator of those programs. In 1938, I was in Warsaw in the center of Hechalutz and I managed to convince my parents to send my younger sister Ahuva to study in Eretz Yisrael. Fortunately, they agreed and Ahuva was sent to Eretz Yisrael and went to a school in Ben Shemen.

In 1939, I was sent to Geneva as a delegate to the Zionist Congress from Eretz Yisrael’s Labor Bloc, where I said jokingly that I had yet to write a novel called From Byteń to Geneva. I returned to Poland, where I remained throughout the war. In 1946, I finally arrived in Eretz Yisrael. It seems that if I were to write a novel it would have to be called From Byteń to the Ghetto Fighters’ Kibbutz.

Roman Frister

My name is Roman Frister, and I was born in 1928. My parents chose to settle in Bielsko, a city with a textile industry in the southern region of Silesia, where the influences of German and Polish cultures met and clashed. The city bordered the Beskids mountain range that sloped down to valleys in gradual declines, green in the summer and white in the winter, creating an atmosphere of peace and serenity. It was only natural to believe that this beauty and tranquility would last forever. I was born and lived in the perfect setting for a happy childhood during my formative years. My home, like many homes in Bielsko, was Austrian in style, rich with decorations. There was a smoking room for my father’s friends, and it had lounge chairs, a portable bar on wheels, and a library built from Georgian walnut wood. I loved to sneak into that room, climb onto a chair and turn the pages in hardcover books that were worn from being read. My father enjoyed success. The city bustled with activity and the developing businesses needed the services of attorneys.

Once a month I was permitted to sit next to my parents’ eminent guests in the drawing room for dinner, dressed in a jacket and tie, so that my mother could be proud of the table manners she taught me. I did not always know how to control the little devil that lived inside me, and sometimes I irritated my parents. In such instances, my father would ring the bell shaped like a dwarf from the fairy tales – and Paula the maid would appear from her place in the kitchen. “Take him to his room,” he would say with a grave look on his face. Paula would give me her hand and I followed her, outwardly looking like a reprimanded child, but inside my heart was overflowing with joy.

About 500 children from wealthy families went to my school. My father preferred that I go to a Hebrew school in order to preserve my Jewish identity in a non-Jewish environment. Our institution was called the Krashovsky Hebrew Elementary School. Befitting a school named for a writer, journalist and Polish historian, the language of instruction was Polish. Starting in the fourth grade, they taught us the Bible and some Hebrew. This was the lip service that the intelligentsia paid to the values of tradition. My father looked for the golden path between the two, and perhaps even among three worlds: Polish culture, German culture and Jewish culture.

Have I told you about my riding lessons? God, how I cursed my father’s love for the cavalry, especially when I would fall from the saddle. Twice a week I had to satisfy his longing for the days he served in the legion of Jozef Pilsudski, one of the fathers of Polish independence, and ride horses that looked to me like wild horses, even though they must have been trained and tired creatures.

If I am not mistaken, I was ten years old when Zeev Jabotinsky visited Bielsko and gave a rousing speech on the repatriation program, and captured my father’s heart in a storm. Perhaps this was the reason why, during the next vacation, I was sent to a summer camp that was sponsored by Betar (the youth movement of the right-wing Revisionist Zionist movement) in the magical vacation village of Cherek, at the foot of one of the most impressive mountains in the region.

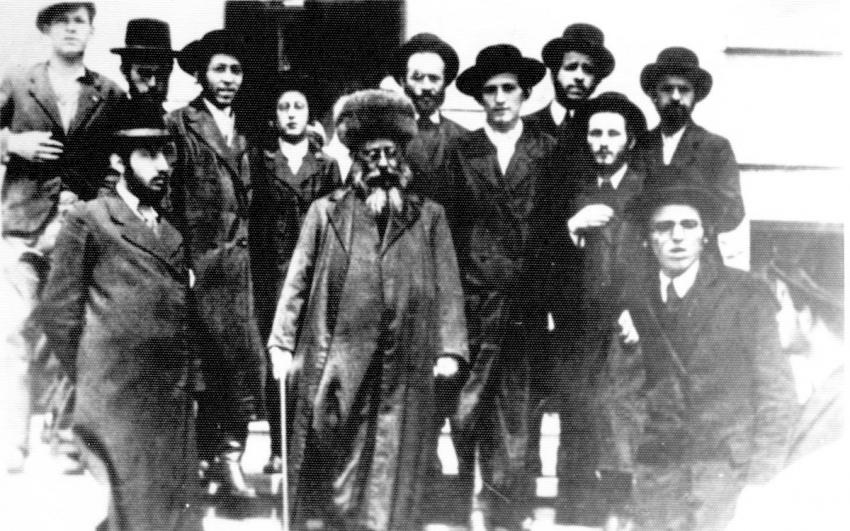

Rabbi Dovid Bornsztain, the Hasidic Leader from Sochtshov

I was born in the year 5635 (the non-Jews called the year 1876). My father, Rabbi Shmuel, was a very important person. He was the “Admor,” which is a great important Hasidic Rabbi and spiritual leader, from Sochtshov. So was my father’s father, who was also called the author of Avnei Nezer (“Stones in the Crown”), an important book that he wrote. My grandfather’s father, as you may have guessed, was also an important rabbi, one of the great Hasidic rabbis, the Hasidic leader Mendel from Kotsk. I grew up mostly with my grandfather (admit it, not everyone has a grandfather called “Stones in the Crown”). I loved living with him, we had a very special relationship and he was actually the person who raised, educated and taught me. I studied Talmud, the Bible, Kabbala and other Jewish mystical texts with him.

As early as my childhood, I was considered to have a great ability for in-depth analysis in the Bible. Even today, it is said that I am a man of uncompromising truth, but when necessary I also know how to be moderate. For example, I insisted on explaining to everyone that the method of learning called “pilpul” (longwinded debate) that was customary in the yeshivas (Talmudic colleges) in Poland, was only a means for clarifying a thought and that it was forbidden to use that method when it had nothing to do with the truth and common sense.

At age 33, I became the rabbi of the city of Vyshhorod, where I established a yeshiva that taught according to the method of Sochtshov. After World War I, and mainly because I criticized the wealthy people of the city (which they didn't like at all), I moved to the city of Lodz. I briefly served as the rabbi of Tomaszów, but due to an internal conflict, I left the seat of the rabbinate, and I even planned to move with my students to Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel). In 5676 (1926), after my father’s death I was granted the important title of “Admor,” and I remained in Lodz where I presided over the Hasidic court. There are students who live near me and there those who come occasionally to ask how they should behave, to be with me on holidays or just to see me. As the Hasidic leader, I continue to foster the study of Jewish biblical and Talmudic literature among adolescents and adults, and I even established a network of yeshivas called “Beit Avraham.” In Warsaw, a biblical journal with the same name, which spread my “Sochtshov” method of learning, was published.

My many other tasks included involvement in political issues. I was one of the leaders of the Agudat Yisrael party, a member of the Association of Rabbis in Poland, and a member of the Board of the Council of Torah Scholars. A few years ago, I visited Eretz Yisrael a few times and I plan on establishing a religious farming community. For that purpose, I purchased land in Eretz Yisrael, and I encourage my Hasidim to settle there.

Yurek

My name is Aryeh and I was born in Warsaw, the capital of Poland. My parents called me Israel-Chaim and my family name is Wilner. At the age of 12 I joined the Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa‘ir (“The Young Guard,” a socialist Zionist youth group) in Warsaw and my life revolved around the movement, whose central goal was Aliya (Jewish immigration to Eretz Yisrael, the Land of Israel). In the youth movement, a new Hebrew name was chosen for me, and my name was changed to Aryeh (“lion”).

I was born on 14 November 1917, the fourth son of Yakov and Dina Wilner. I had two older sisters, an older brother and a younger sister. My father had a workshop and a store for leather goods and always had an income, so we belonged to the middle class.

With my father we spoke Polish and Yiddish. He was educated in a traditional school, and that was his language. My mother was from Warsaw, from birth. She was proficient in Polish literature and culture. Among ourselves, we spoke only Polish. In the youth movement I learned Hebrew. I think that my parents would have considered themselves Warsaw-Polish people.

I went to a private Jewish elementary school whose goal was to prepare us for continued education in the gymnasia. I did, and I went to the public Polish gymnasia and was one of the few Jewish students. When I joined Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa‘ir, my parents were quite dissatisfied. They believed that my future was in my studies, so it was not a good idea to join a youth movement. I, on the other hand, saw my future in the fulfillment of the Zionist idea. The arguments between us became more and more serious since I spent increasingly more time with the youth movement, and less and less time in school. At the end of the tenth grade, I decided to leave school. My parents were very angry and I finally agreed to take my matriculation exams on the condition that I study independently. Ultimately, at age 17, I had to go on hachshara (a communal Zionist agricultural training program) with my friends from the youth movement and I did not matriculate.

In Ha-Shomer ha-Tsa‘ir's Giladi Division, I was introduced to Jewish culture, Hebrew, and most importantly, to Eretz Yisrael. Every holiday we would sit together and sing songs about Eretz Yisrael, in Hebrew of course. We celebrated the holidays in a pioneering way, which is different from regular celebrations. I especially loved to read, and I read in Polish and a bit in Hebrew. My favorite authors are Herman Hesse and Roman Rolan, very famous authors who belong to the genre of romantics who espouse the relationship between man and nature.

I ultimately went to Slonim for a very short while. On 1 September 1939, I visited my parents in Warsaw and planned to lead a group near the city of Lodz. The war broke out and I escaped to the east with a large group of my friends. After many hardships, my friend Peppe and I reached Vilnius, where it was very difficult, mostly because I missed Warsaw: family, friends, culture, and the place itself. I arranged a “reading room,” the only place possible to sit and read quietly in our friends’ apartment. In February 1941, Peppe received authorization to go to Eretz Yisrael and I stayed in Vilnius. I worked as a set manager and as a graphic artist and waited my turn. I used to say that “the road to Eretz Yisrael does not go through Warsaw,” meaning that I am not going back to Warsaw as long as the Germans are there. On 22 June 1941, the Germans invaded Vilnius and I believed less and less that I would soon see Eretz Yisrael.

Julian Tuwim

My name is Julian Tuwim. I am a poet.

How is a poet born? That is a big riddle. I grew up in a city far removed from poetry, the city of Lodz. Lodz was an industrial ugly city, the Polish Manchester. A textile industry city, where there was ostentatious wealth right next to distressing poverty.

I was born in 1894 to a middle class Jewish family. At home we spoke Polish and on the street German, Polish and Yiddish. I learned in a school where the official language of instruction was Russian.

My mother came from a totally assimilated family. Her father was the editor of one of the main newspapers in Lodz. Two of her brothers were attorneys and two others were doctors. One sister was married to a Polish author and the second to an engineer, Adam Czerniaków, who later became the head of the Judenrat in the Warsaw ghetto. A distant cousin of my mother’s was the famous pianist Arthur Rubinstein and whenever he arrived in town for performances, we received free invitations.

The revolution of 1905 was a moment of great change. A pogrom, Cossacks galloping through the streets, the workers’ struggle (Jews and Poles together) and the perpetrators of the pogrom, barricades in the streets, and finally closure of the school by the students.

In the end, we no longer had to learn Russian. What a pleasure!

In 1916, I moved to Warsaw to study law. But I didn’t like the studies, and I continued writing poetry in Polish. The language just flowed from within me, perhaps a direct influence from the books in my mother’s home, from our simple nursemaid Antonia, and from our outdoor games.

When Poland was liberated from occupation by the Russians, Germans and Austrians, and was granted independence after more than one hundred years of bondage, I felt a burst of freedom and redemption as a Pole, a Jew and a poet. Together with my poet, artist and actor friends, we established a modern coffee house and even published a satirical newspaper. We really went wild, we ridiculed the old world. I recited my love poems and my nature poems and believed in my future and in what I believed it held: an independent state, freedom for all, and equality.

My first book of poetry that was published was a terrific success. But the Polish right wing hated me and my great talent in “their language.” They claimed that I was a Jew who wrote in Polish, that my poetry was saturated with Judaism. I showed contempt for them.

I wrote poetry, plays, and translated from Russian, German and French. I wrote political poetry that expressed anti-military viewpoints. They threatened me with beatings, and I was scared… I was happily married to the most beautiful woman in Warsaw. In the coffee shops that I frequented, I was surrounded by fans. The right continued to slander me, but the children of the slanderers enjoyed my wonderful poems for children, like all Polish children to this day.

The 1930s gave rise to the fear of Nazis in me. I feared how the world around me was deteriorating, and with the German invasion I escaped Poland for South America, and from there to New York, where I wrote Polish Flowers, the greatest of my creations.

Ludwik Hirszfeld

I was born in 1884 in Lodz. Since I always dreamed that I would be a scientist and a doctor when I grew up, I studied in the best medical schools in Berlin and in Heidelberg in Germany. In Heidelberg I was part of a research team that discovered the blood groups, after which together with my wife I received a job as a researcher in Zurich.

The Great War, the World War I, broke out. I of course did not want to return to Poland, since there they would have drafted me into the Russian army. I didn’t want to join the German army, either. I heard that the Serbs needed help with their struggle against epidemics, and since that was my expertise, I worked all of the war years as a civilian physician in the service of the courageous Serbs.

At the end of the war, I returned to the land of my birth, Poland, to the city of Warsaw. Warsaw received me with open arms. I taught in the faculty of medicine in the university in the city, and I founded the government company for public health. I fought to instill public awareness for cleanliness, personal and public hygiene, and I continued my research, essentially in the field of vaccines and their relationships to blood groups. I published hundreds of scientific papers in the world press and I was the Polish delegate to countless international scientific conferences, where I met my colleagues from research and from my student years.

During the 1930s, I began to feel the change that was overcoming my friends and peers in Europe, the Italians and mainly the Germans. Researchers from these countries began to relate their research to the theories of race, and I failed to understand the connection between that and science. Their attitudes towards me also changed unexpectedly. At the beginning of the academic year, the rector of the university claimed that the Polish students did not work hard enough since the Jews begin their studies in the faculty when they are 10% of it, and finish when they are 35%. One of the students even claimed that Jews should be barred from studying in the university. I was shocked by the situation. Aside from my ethnic origin I felt no connection to the Jews, and even in the religious sense, I was Catholic.

[During World War II, I found myself in the ghetto. Me, a world famous professor whose articles were published in Germany! It was hard for me to get used to the Jews in the ghetto, I did not understand them very well. But there was so much disease there that I spent my days and nights saving lives.]

Abrasha (Abraham) Blum

My name is Abrasha and I was born in 1905 and raised in Vilnius. Vilnius was known as the “Jerusalem of Lithuania” and was a center of Jewish life. I was a very lucky kid since my father owned a sweets factory. It was like living in a dream.

I grew up in a Zionist traditional home. This meant we kept the Jewish tradition but we were not religious, although I studied in the “Cheder” (Jewish religious elementary school) where they were quite strict with the religious laws. So why did my parents send me to the “Cheder”? Good question…

When I was fifteen years old and studying in the Jewish Gymnasium, the Red Army occupied my hometown. You should have seen it. The soldiers proudly marching with the red flags in their hands; the slogans about equality and fraternity between all humans regardless of their religion, race and sex in their mouths. I was exposed to these ideas for the first time and they changed my whole life.

The Bolsheviks with their banners and slogans ruled Vilnius only for six weeks. They left and Vilnius became the capital of Independent Lithuania. That didn’t last for too long either and shortly afterwards, the Polish army came in and Vilnius became part of Poland. I tell you, it was quite tiring changing all these national identities from Russian to Lithuanian to Polish and above all, Jewish.

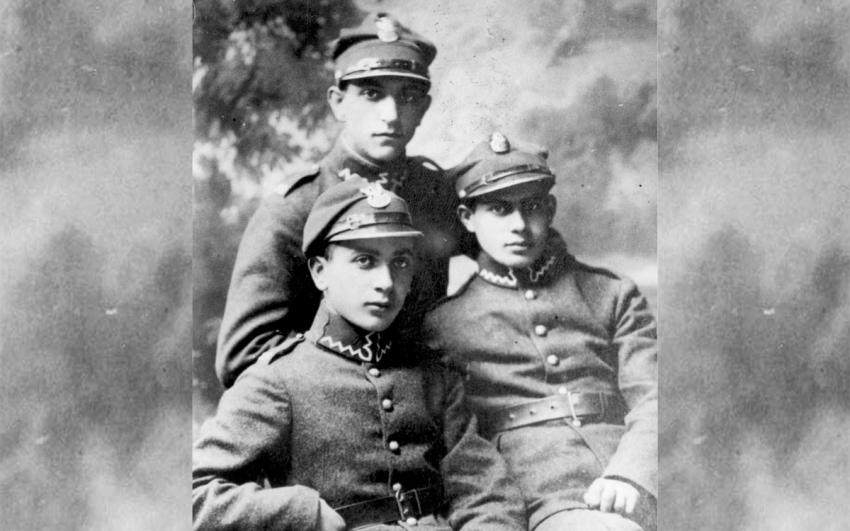

I continued my studies in the Gymnasium and being influenced by the Communist ideas I joined a communist group. Everybody in this group was equal. Religion didn’t have any significance. But I understood after long debates that actually my Communist friends didn’t recognize the needs of the Jewish worker because they didn’t see Jews as a people. My Communist friends didn’t show any sympathy for the problems of the Jewish proletariat and therefore I joined the “Tsukunft”, a Jewish youth movement whose name means “The Future”. It belongs to the Bund, the Jewish Socialist Party in Poland.

I graduated from the Gymnasium and decided to continue my studies abroad. I first went to Germany and then graduated from my engineering studies in Gent in Belgium. I had to go back to Vilnius because my father passed away, and when I was there, I was drafted into the Polish army.

After my discharge from the military, my girlfriend Liuba and I got married and moved to the great capital, Warsaw.

The move to Warsaw had a significant impact on my life. For the first time, my political activity became a central theme in my existence. Together with my friends, Pinchas Schwartz and Alexander Ehrlich (whose father was a great Socialist Jewish leader), I became an important figure in the movement.

I began publishing articles in the “Tsukunft” newspaper, the “Yugent Werker”, which means “The Young Worker” in Yiddish in case you were wondering. Why Yiddish you may ask? Well, Yiddish is the language of the Jewish people and especially of the lower classes and therefore the newspaper was in Yiddish as were our conversations, debates and speeches. It is the mother tongue of most of Poland’s Jews!

I worked and lived in Warsaw and wandered for eighteen months throughout Poland, establishing new branches for our movement. Through these travels, I became more and more involved in the party leadership.

Today and for the past three years, I am a member in the central committee of the “Tsukunft”. The peak of my career up until now is the fact that I was elected as a member in the city council, as a representative of the Bund of course.

Marek Edelman

My name is Marek Edelman. I was born in Homel in 1919. My parents, Nathan and Cecilia, were very active in politics and supported the Bund, which was the strongest and largest Jewish socialist party in Poland. I was proud that my parents belonged to it. Shortly before I was born, my parents moved to Warsaw. There, in addition to their work, they were engaged in various political activities. In 1924, my father passed away in Warsaw. My mother was a manager of a hospital laundry and later became cashier in the Monopol Hotel. She was the one who shaped my political views. She belonged to the women’s organization of the Bund. She dreamed of a Poland that was free of antisemitism and where the rights of the Jews and Jewish workers were respected. She believed that the place where Polish Jews belonged is actually here, so she didn’t agree with the Zionists, who wanted to create their own state in Palestine.

She sent me to the Bundist school, where I obtained a secular Jewish education. I belonged to Skif, the Bund organization for teenagers. When my mother passed away in 1934, the party friends took care of me. Later, I lived with Rosa and Salek Lichtenstain, who were the neighbors of my parents. I began to work in order to earn a living. Just on the eve on the war, I joined Tsukunft, the Bund’s youth department. I felt like a fish in water there.

The end of the summer vacation 1939 I spent with friends and colleagues in Brog nad Bugiem. Everybody knew that the war was about to start. When I returned to Warsaw, I saw mobilization posters, which called to report to the main rail office in the Praga district. The next morning, crowds of young people crossed the bridge to Praga in order to join the army. I also went there, but when I arrived, no one was there in the building. I returned home, went to sleep at night, and the next morning I heard on the radio that the Germans had crossed the Polish border.