Grades: 9 - 12

This learning environment centers on the life cycle of Jews who lived in Salonika, Greece before, during, and after World War II. The Jewish community of Salonika was one of the most ancient in Europe. Before World War II, 55,200 Jews lived in Salonika, comprising two-thirds of the population. By the end of the Holocaust, only one thirtieth (1,950 souls) of the Jewish population remained. This educational unit presents a case study that can help teachers and students find an example of how to uncover and reconstruct the life of a particular community through a variety of materials.

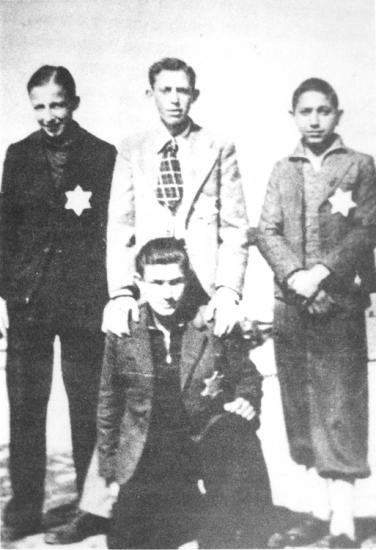

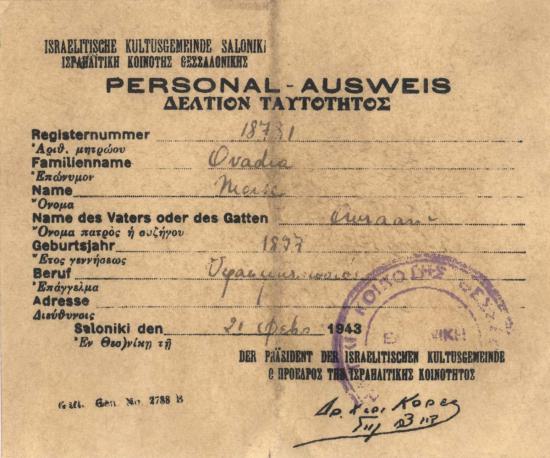

The theme for this year’s Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Day is “The Faces Behind Documents, Artifacts, and Photographs.” These various items are memory fragments that remain after the devastation of the Holocaust. It is with these remains that we try to recover and try to envision the lost Jewish world and especially the faces of the people who lived then. The unit before you utilizes materials found on Yad Vashem's online databases. Using historical sources, photographs, artifacts, films, and other forms of evidence, we have attempted to depict the Jewish community of Salonika, before and after the Holocaust.

In addition, you will find the presentation in a form that can be download for use in the classroom, ceremonies to mark Holocaust Remembrance Day, and lesson plans, which may all be downloaded. Teachers and students also are invited to create similar environments to commemorate and honor other communities, using Yad Vashem’s online databases.

Supplemental presentation to use in class

Supplemental presentation to use in classIntroduction

IntroductionToday, Salonika is the second largest city in Greece, home to roughly 4,500 Jews, 0.05% of the total Greek population. However, the population was not always so meagre. Before 1942, Greece was the hub of European Jewry, a center for Torah learning attracting students from all over the world. The first Jews were thought to have settled in Greece over 2,000 years ago and as time passed the community thrived and expanded.

After living under various rulers for over one thousand years, the arrival of the Ottoman Empire in Greece in 1430 improved life for the Jews of Salonika. The Turks lifted taxes and removed bans that had been placed on them by previous Venetian rulers. In 1492, when Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, expelled Jews from their kingdom, these refugees were able to enter Greece uninhibited. Greatly influenced by the large influx of Sephardic and Converso Jews, a rich Jewish culture flourished.

The Jewish communities that existed from the Turkish regime until the Greek Conquest in 1912 were notable for their stable economy, their rich religious and cultural tradition, and their flourishing communal leadership. The Jews in the southern areas that had lived for a long period under the Greeks had become more assimilated into the general population, and used Greek as their daily language. Their relations with their Greek neighbors were good until the rise of Greek nationalism in the late 19th century.

On the eve of World War II, approximately 80,000 Jews lived in Greece, residing in 31 localities. In 1945, the Jews of Greece numbered only 10,000. 87% of Greek Jews were murdered in the Holocaust.

Before the Holocaust

Before the HolocaustSephardic Jewry

A Sephardic Jew is a descendant of or follows the traditions of the Jews of the Iberian Peninsula before their expulsion in the late 15th century. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” is derived from the word geographic location “Sepharad,” the Iberian Peninsula, and modern-day Spain. Many Sephardic Jews lived in Salonika, especially after 1492 when they were expelled from Spain and Portugal and welcomed by the Turkish leaders of the time who believed the Jewish population could have a positive effect on the local economy. Although Spanish Jews were brutally deported from their land, they continued using Judo-Spanish, or Ladino, as their central language in both learning and common day life.

Religious Life

During the 16th through the 18th centuries, Salonika also became a center of Torah learning, and of Jewish mystical tradition, attracting many students from abroad who came to study with respected Torah scholars. During the 16th century there were several important rabbis whose influence spread beyond Salonika and even beyond the Ottoman Empire. Religious writings from Salonika were published throughout the Jewish world. Religious life of Jews in Salonika expanded and flourished with the influx of immigrants from Spain and Portugal. They founded separate synagogues (congregations), named after their native countries or towns such as Castilia, Catalan, Aragon, Majorca, Lisbon, Sicilia, Calabria, Puglia, and Provincia. Out of the tens of different synagogues, each with varying traditions, only one was Eastern European/an Ashkenazi synagogue. Shortly before the outbreak of World War II there were twenty rabbis, ten Jewish butchers, four yeshivas, and four Torah scroll writers in Salonika, a testament to the observance level of the community. Today, only two synagogues remain.

Professionalism

As the years unfolded, the Jews of Salonika were able to excel in their chosen industries. They worked as artisans, dying silk and crafting gold and silver in the 14th century, as tradesmen of goods and in industry from the 17th century onwards, and as stevedores in the 19th and 20th centuries. As commerce grew so did the community from 25,000 Jews in the 17th century to 80,000 in the 20th century. In Salonika the Jews were not prohibited from working in different trades as they were in the rest of Europe; some were even able to train as doctors and lawyers. Antisemitism existed but it was not as rife as in other European countries. The Jewish residents enjoyed certain civil freedoms that allowed their community to thrive.

By the 1900s many people from the community worked in the docks as stevedores so much so that on Shabbat and on Jewish holidays the dock came to a standstill. The Jewish stevedores were famous all over the world for their skills and abilities, and a number of them moved to Palestine and started working in the port of Haifa.

Education

Education is strongly emphasized among Jewish communities, and children from very young ages attend school. Thus the Salonika Jews were no different in believing that a good education is of great importance as the key to creating a culturally and economically wealthy community. The thousands of children living there went to Jewish schools where they learned mainly in Ladino. Alfons Levi, the Secretary of the Jewish Community, recalls:

“There being two government run schools and two private schools while three thousand other children learnt in youth homes which were educational institutions for children with working mothers. The children were taught religion and Hebrew in addition to other classes for four hours a day. Seventy-one of the teachers were actually Christian, and fifty-two of them were Jewish. Only two hundred and fifty children from the more affluent families were able to also study in the Greek gymnasium. In 1873 the Alliance Network established the first really westernized schools in Salonika. The network was created in France in the 1860s, with the purpose of protecting Jewish identity and encouraging education within communities all over the world. Seven schools for nursery, elementary and vocational ages were opened in Salonika that served to educate four thousand children of both sexes.”

1

Salonika was unique in comparison to many towns in Europe, because Jews were allowed to attend university 1920s. Fifty Jewish students were part of a teachers seminar and twenty were preparing to teach in Jewish schools. As physicians who had trained in Europe entered the community, advancements in medicine and education meant that Salonika developed into a more modern and liberal society. Salonika was also famous for its religious education. 1,500 students attended several yeshivas and a Talmud Torah school with roots dating to the 16th century. The yeshivas of the town were also renowned for their knowledge of Jewish mysticism i.e. Kabbalah. After the Greek occupation of Salonika in 1913, the Greek government implemented a policy of Hellenization in order to enforce Greek language and culture and unify the minority population. As a result, the Greek authorities wanted to establish a Greek Jewish educational framework, aimed at assimilating the Jewish population. Resisting this, in 1924 the community refused a proposal for the funding of schools through the state, enraging the nationalistic circles of Salonika.

Newspapers, Literature, and Cultural Life

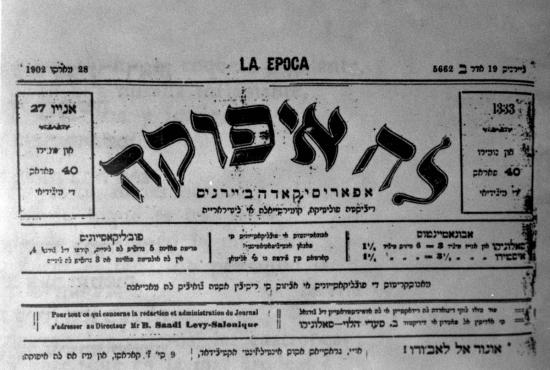

A rich artistic culture thrived in Salonika. Even though writing as a profession was sometimes looked down upon, newspapers, poetry, folk songs, and plays were popular, the majority of which were written in Ladino, with others in French and Hebrew. In the late 19th and first half of the 20th century, approximately 35 out of the 70 local newspapers were published in Ladino. The papers reported on a plethora of topics including national and international politics and the activities of the local community, while serving as a space for ideological discussions that reflected the social and political opinions of its writers. For example, the paper "Solidandad" encouraged Socialism, urging those working in industry to strike and criticise the New Turks government. While Zionist papers encouraged the Zionist ideal "La Epoca" (add photo here), the longest running paper published from 1875 through 1911, openly rejected it, encouraging the Jewish community to learn Turkish to become more involved in local bureaucracy/administration and commerce.

Reading was just as important to the Jewish community. However different in their political affiliations, most of the literature written by the Salonika Jewish community encouraged the community’s progress and development through education and economic advancement. Plays were written specifically to emphasize the importance of such progress with the dual use of the performance as a fundraising event for the local community clubs. Songs and poems written in the traditional Cantigas style and accompanied by instrumentation, revolved around the harsh realities of life and were also performed in the theater and played an important part in holiday celebrations and at family gatherings. The bands that wrote and performed them were often made up of Jews of different backgrounds, but still they were written in Ladino, showing the strength of this language within the cultural space of Salonika.

Food

When a community is in exile from its homeland it often clings to the cultural tendencies that defined it, as a reminder of the familiar. Food holds a special place in a Jewish home and community, as part of ritual, Sabbath, and holiday customs, and as part of the large tapestry of Jewish culture and traditions. Each community’s Jewish cuisine has largely been influenced by its local surroundings and climate.

Traditional Sephardic foods consist of borekas and pastelitos(pastry stuffed with various fillings), and the famous guevos haminados that can be traced back to the Jewish age in Spain. Translated as “oven eggs,” these beautiful eggs boiled or baked with onion peel and oil, reveal an almost-religious connection to food. They are an integral part of the Jewish Sephardic cuisine, reflected by their presence in Jewish folklore. Many Sephardic Jews today still remember the smells and tastes of their foods, and explain how these culinary specialties are central to their culture and memories of past history.

- Statement by Alfonso Levi to the 6th Bureau of the Israeli Police that headed the investigation of Adolf Eichmann. Mr. Levi was the secretary of the Jewish community of Salonika before and during the Nazi occupation. Yad Vashem Archive, TR.3 / 237.

- Alberto Nar, “Folk Songs of the Holocaust of the Jews of Thessaloniki,” in Cultural forum: of the Jewish community of Thessaloniki, Ir Vaem Beisrael, (Thessaloniki: Jewish Community of Thessaloniki, 2004), 41.

During the Holocaust

During the HolocaustPolitical Developments and Antisemitism

Until the 20th century, the Jews of Salonika were not the victims to the kinds of antisemitism and oppression evident in Eastern Europe in the same years. Although they remained somewhat segregated from the other inhabitants of Salonika, and did experience periods of antisemitism, they had many freedoms in the realms of culture, education, and in their chosen professions. However, in the early 1900s, the political situation in Greece was incredibly volatile. Although it had been many years since Greece had broken from the Turkish-controlled Ottoman Empire, wars over land were still being waged, as were political battles inside the country itself. In 1917 a new Turkish government came to power, pushing out the royal establishment. Jewish soldiers fought alongside their fellow countrymen to support their new government, unaware of the repercussions nationalism would have upon their communities as Salonika became a symbolic battleground for the construction of a Greek national identity.

The new government encouraged vigorous state nationalism, and wanted its citizens to reinforce Greek identity. Jews became a clear target because of their refusal to assimilate into Greek society. In having their own separate governing bodies, schools, courts, neighborhoods and even a separate language, Jews had sustained and developed their own identity. They were seen as outsiders because of their extreme differences in customs and cultures.

In 1917 a great fire took place in the city. Many of the homes that were burned down belonged to the Jewish community. The government wanted to take this unexpected clearing of the city as a chance to Hellenize it, and in doing so, refused to let many of the Jews rebuild their homes in this area.

In 1922 a law was imposed forcing all inhabitants to refrain from work on Sunday, which had the potential to harm Jewish commerce. Even though this law wasn’t successful in its enforcement, it still forced many Jews to leave Greece.

The year 1926 saw the first major campaign against Jews in Greece. Pamphlets were typecasting Jews as Zionists and communists who were behind a separatist plot against the state. The pamphlets encouraged the citizens of Salonika to boycott Jewish businesses.

Restrictions on the number of Jews permitted into universities were imposed in 1927. Such rules had existed for many years in some countries in Europe, but in Salonika Jews had been able to live without such restrictions. Even a few mainstream newspapers began to support the cause, encouraging antisemitism.

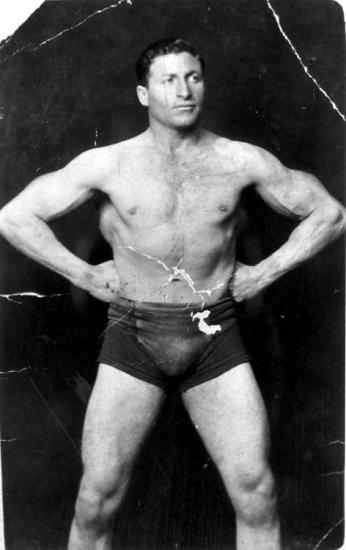

The Jews had long sustained links with other communities throughout Europe and the creation of the “Maccabi” Games, for example, was a chance for members of the Diaspora to come together, in this case, to celebrate athletics. Greek nationals regarded such events as suspicious, and accused Jews of plotting against Greece.

In 1927 the EEE (Ethniki Enosis Elladas) or National Party of Greece was formed. Espousing antisemitic overtones, this political party only allowed Christians to join its ranks. This party was later accused of being the main aggressors in the 1931 Campbell Riots, which resulted in the burning down of an entire Jewish neighborhood.

In late 1929, the local authorities as the Jewish community to give up a large portion of its cemetery to help house the numerous refugees that were overcrowding Salonika. The Jews explained that moving the dead was against Jewish law but to no avail. The council insisted that using the land was not antisemitic because parts of the Muslim and Christian cemeteries were also being allocated for the same purposes. Within a month, a group of youths had desecrated many tombs in the cemetery, yet the Council of Ministers refused to supply extra security.

German Occupation, Ghetto, and Deportation

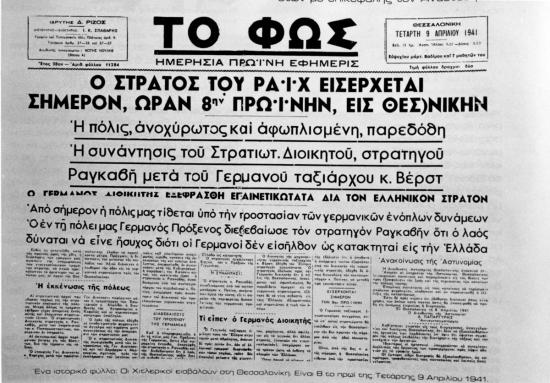

After the occupation of Greece, the country was divided into different zones, each under one of the occupying forces: Germany, Bulgaria, and Italy. Salonika was under German occupation. Before the German invasion of Salonika on April 9, 1941, many members of the Jewish community were imprisoned. The Jewish community was subjected to the Gestapo, and was ordered to pay for the maintenance and finances of its people. Jewish organizations and schools were closed and Jewish street names were changed to Greek names. In Salonika, as elsewhere, the Germans robbed Jewish property before and after deportation. They tortured rich Jews and stole cash, jewelry, silverware, art pieces, and carpets from them. Most of the booty they collected was sent to Germany on trains and airplanes. Apartments, offices, and shops of Jews who had been deported were given to “loyal” executives.

The confiscation of houses, goods, and grains in the city created severe food shortages. Famine caused the spread of infectious diseases. The Jewish community tried to help the hungry through the establishment of kitchens for the needy. A special unit called "Commando Rosenberg” came to Salonika in mid-June 1941. The unit was headed by Dr. Johann Paul, director of the Hebrew Department at the Institute for Jewish Research in Frankfurt, which received information from its Nazi colleagues on the valuable collections in the city. The unit systematically confiscated tens of thousands of rare books and manuscripts from city libraries and private collections. They confiscated Torah scrolls, prayer books, scrolls, and ritual objects such as the curtains from the Holy ark that holds the Torah scrolls. "One of the important things we did in that critical period was distribute books and resources to neighboring families, so that they could keep and guard them. We had very rare books, including books in Ladino."

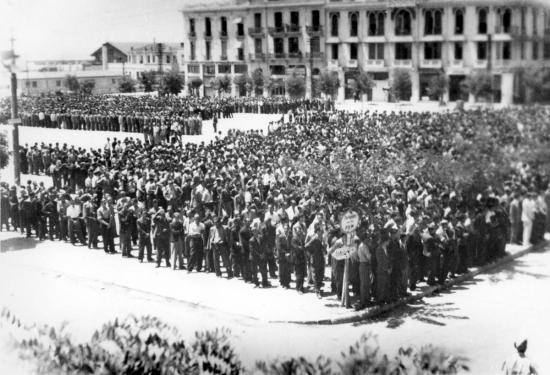

Among the events that left their impression indelibly marked in the memories of Jews of Salonika, was "Black Sabbath." Following the decree that ordered all Jews between the ages of 18 to 45 to report for forced labor, some 6,500 Jews presented themselves on Saturday, July 11, 1942, at Liberty Square in Salonika. They were forced to stand for long hours in the blazing sun, suffering abuses from the Germans. After four days of registration, the Jews were drafted for forced labor in road construction as well as other areas of labor. Many perished due to poor nutrition and exhausting labor.

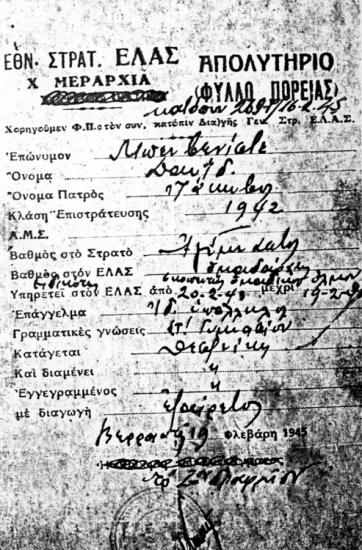

The Jews of Salonika began to leave the city with the progress of the German occupation even before they entered Salonika. On July 15, 1942, the Italian consul reported that 1,200 Jews left Salonika for the Italian zone, mostly to the city of Athens. Some returned to the city in order to close their affairs, but were trapped there, unable to escape. Some of the wealthy and well-respected Jews of Salonika moved to surrounding villages. Most successfully left the city by using false documents; others posed as villagers or train employees. No precise data on the flight of Jews from Salonika to the Italian zone exists; estimates range from 3,000 to 7,000 people during the years 1941 to 1943.

The Germans resorted to various methods of deterrence in order to prevent escape attempts, including public executions. Escape attempts diminished even with confidence in German promises. For example, there is the story of Jackie Handly whose father bought tools for the trip to Poland, so that he would be able to support his family there.

A few days before they started transports from Salonika, in the midst of negotiations to save the Jews of Slovakia, Dieter Weslicini, an aid to Adolf Eichmann in Bratislava, stated that what was happening to the Jews of Salonika was not all bad. At the same time he conducted the preparations for their deportation. The Jews on the transports were entitled to be released if they were from Axis countries such as Italy, as well as subjects of neutral countries such as Turkey and Spain. There were 850 Jews in Salonika who belonged to this category, more than 500 Jewish subjects of Spain, about 280 Italian nationals and nationals of Turkey, Portugal, Argentina, Switzerland, Egypt, Hungary, and Bulgaria.

Germans allowed those being deported to take a small amount of personal belongings with them, in the amount of 20 kg (44 pounds) per person. For five months, transports left from Salonika to Auschwitz from the station in the nearby neighborhood of Baron Hirsch. Transports left every few days and the Baron Hirsch ghetto was emptied and filled before each transport. The transports of Jews from Salonika also included Jews from other communities such as Thrace and Macedonia. 2,800 Jews were cramped into 40 cattle cars (about 70-80 people per car) on the first transport. To further the deception, each head of a family received a check for 600 Polish Zloty, and the Germans spread rumors that their property would be returned after the war.

Greek Jews in Auschwitz

According to German records, from March 20, 1943 to August 18, 1943, nineteen transports arrived from Salonika to Auschwitz, including 48,533 Jews. However it is known that the transports arrived to other camps, including Treblinka. A minority of deportees passed the initial selection upon arrival (11,200 in total: 4,200 women and 7,000 men). The fate of the Jews of Salonika in Auschwitz was unique for several reasons. Unlike most Jews deported to Auschwitz, who came from eastern, central and western Europe, the Jews of Salonika were not used to the extreme weather conditions that prevailed in Poland. In addition, communication was extremely difficult because the common languages among the Jews of Salonika were Ladino, Greek, and French, and not German, Yiddish, and Polish, which were the most common languages in Auschwitz. These reasons made it difficult for the absorption of the Salonika Jews as camp prisoners, most of whom had lost their family members upon arrival in Auschwitz.

For Germans, the Jews of Salonika made up a large and important labor force in the camp. The occupational profile of Jews of Salonika before the war helped them integrate into a variety of work forced upon them by the Germans. Their physical abilities were known among the Germans and these prisoners became a cohesive group within the larger group of forced laborers. The prisoners from Salonika were employed in building barracks and crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau and worked to gear up and build the factory at Monowitz (Auschwitz III). In addition, many were sent to work companies outside the camp and forced to work in mines or farms. In autumn 1943, several hundred prisoners from Salonika were sent to the work camp Genshovka, located on the ruins of the Warsaw Ghetto, and were forced to clear the rubble of the ghetto. As the Red Army approached, the Greek prisoners were taken to concentration and work camps in Germany.

- Rivlin, B. [Editor], Book of Communities - Greece, Thessaloniki (Pinkas HakeHilot, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1998), 276-282.

- Rivlin, B. [Editor], Book of Communities - Greece, Thessaloniki (Pinkas HakeHilot, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1998), 276-282.

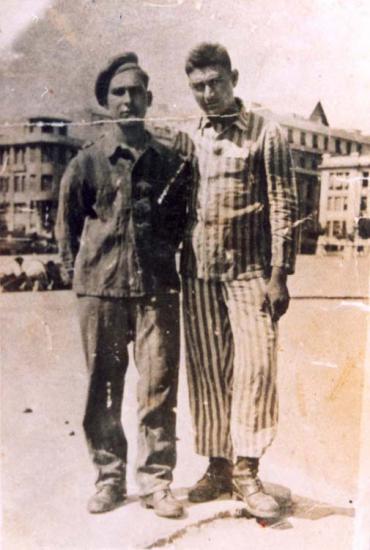

After the Holocaust

After the HolocaustShlomo Cohen was born in Greece in 1920. He was deported to Auschwitz - Birkenau, and the British army liberated him from the concentration camp Bergen-Belsen. He immigrated to Israel in 1946. Shlomo tells part of his story:

"... They told us that we could register - or return to Greece, or travel to Israel or to the United States. I signed up for two places: Greece and Israel, but I wanted to return to Greece and wait several months to see if anyone from my family survived ..."

5

After the war ended in 1945 there were 2,000 Jews in Salonika out of some 10,000 Greek Jews who survived the Holocaust. The few survivors of this magnificent community, returned to Salonika in the hope of finding family members, relatives, and friends, who also survived. Most survivors did not find relatives who were still alive and the harsh realization began to set in that they were the few survivors from their families and communities. It was another step in mourning after the Holocaust. Some survivors were struggling to regain some of their family property and rebuild their lives in Salonika, but most chose to start their lives anew in Israel, the United States, Canada, Australia, or South America. Life Holocaust survivors from other countries, survivors from Salonika struggled to gather fragments of their previous lives in order to build new lives and establish families. Survivors who immigrated to Israel took an active part in building their own country and society.

- Kleiman, Yehudit and Springer-Aharoni, Nina, The anguish of liberation - Testimonies from 1945, Yad Vashem.

Photo Gallery

Photo Gallery

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 5535_4

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4301_4

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 6941_12

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 6941_15

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 8759_ 12

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4301_6

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4301_8

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 6941_5

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 87CO6_

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4301_1

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 6941_55

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_26

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_20

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_24

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 87DO5_

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 6941_10

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 89CO8_

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 89CO9_

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_13

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_18

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_39

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4613_550

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4667_1-2

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3290_22

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 3532_11

Museum Artifacts Collection, Yad Vashem

Courtesy of Państwowe Muzeum Auschwitz-Birkenau, Oświęcim, Poland

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 210_107

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 210_110

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 4419_

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 5997_2

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 5997_4

Yad Vashem Photo Archives 6093