Grades: 9 - 12

Duration: 1 - 1.5 hours

Didactive Objectives

- Learn about the unique self-sacrifice and actions of Righteous Among the Nations, through the story of Chiune Sugihara, a diplomat from Japan, who helped Jews escape during the Holocaust.

- Sensitize students to matters of emotional intelligence - social awareness to the plight of the other.

- Discuss issues of personal responsibility, conscience and moral dilemmas relating to difficult decisions.

Introduction

In this lesson plan, we will learn about Chiune Sugihara, who jeopardized his family, career, livelihood, and life to issue over 3,000 (confirmed) crucial transit visas for Jews whose lives were threatened by the impending invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany, whilst he was acting as consul at the Japanese Embassy in Kovno, Lithuania. Confronted with an urgent situation of humanitarian proportions, he looked into his heart and conscience in defiance of the orders of the Japanese government.

Note to Teachers:

We have divided the text below into five sections. Choose five students to read each section aloud. This allows students to listen carefully to the terminology that Sugihara used - “I felt,” “I had to,” “I couldn’t.” The words have to be said and heard in order to internalize the underlying meanings and educational values.

Background

“I may have disobeyed my government, but if I hadn’t I would have been disobeying God.”

Chiune Sugihara

Chiune Sugihara was born on January 1, 1900 in Yaotsu, near Nagoya, Japan. He graduated from high school with top marks and attended Tokyo’s prestigious Waseda University. He took a job, which enabled him to pay for his own studies, and later decided to enter the diplomatic service, receiving a scholarship to study at the Japanese national language institute in Harbin, China. There he studied Russian and graduated with high honors.

While serving for the Japanese government in Manchuria, China, which was then under Japanese control, he was disturbed by Japanese military policy and the cruel treatment of the Chinese. As a result of his action, he resigned his post in protest in 1934. The following year, he volunteered and was assigned to the European section of the Japanese Foreign Ministry, and in 1937 was posted to the Japanese embassy in Helsinki, Finland.

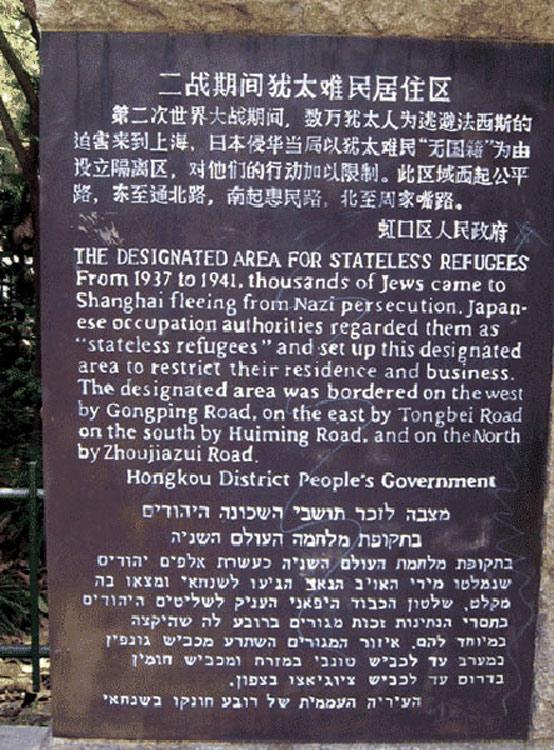

In October 1939, Sugihara, his wife and children were sent to Kovno, Lithuania, by the Japanese Foreign Ministry to open a consulate. As part of his job in Kovno, Chiune Sugihara monitored the maneuvers of the German Army across the border, so that Japanese headquarters would know in advance of the anticipated German attack on the Soviet Union. The consulate was a small walled-in house in a quiet residential area, and the first few months there were very peaceful.

However, not long after settling into his new job, a wave of Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi invasion of Poland flooded into independent Lithuania. The Jews saw Lithuania, as yet, an independent state, as a safe haven. They brought with them chilling tales of Nazi atrocities against the Jewish population. Until then, Sugihara had not been aware of the rise in antisemitism and the persecution of European Jewry.

“We didn’t have much knowledge of what they were. We knew that they were generally unwelcome in Europe, but that’s all.” We did not like them or dislike them.”

In August, 1940, the Soviets occupied Lithuania, (part of the Molotov-Ribbentrop agreement) and instructed all foreign diplomatic missions in Kovno to close. One morning, as he was packing his belongings, Sugihara was surprised to notice a huge crowd of people gathering outside his home. Sugihara was informed that a Jewish delegation was waiting in the yard, asking to see him. Dispatching his Polish-speaking secretary to find out what these people wanted, he was surprised by the message delivered to him which, as orally reported by his Polish-speaking secretary read as follows:

“We are Jews. We have lived in Poland, but we will be killed if we are caught by Nazi Germany. However, we don’t have any visas to escape. We want you to issue Japanese visas.”

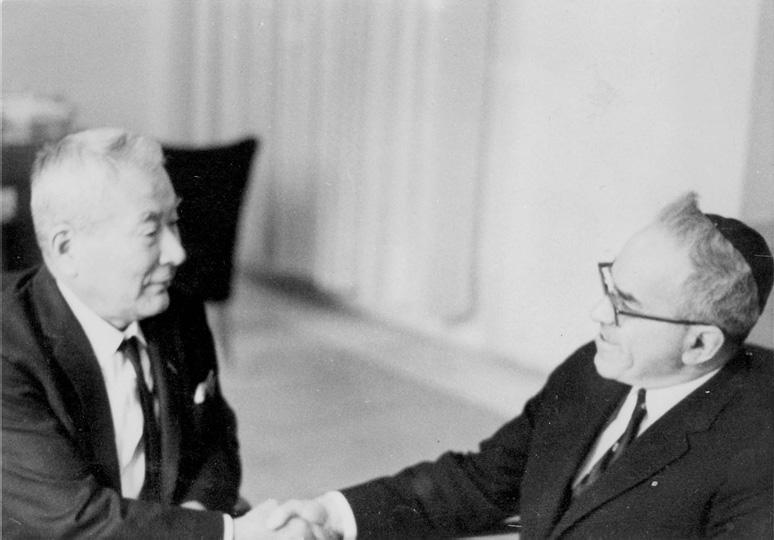

Chiune Sugihara agreed to meet a delegation of five people led by Zorach Warhaftig, a Jewish leader who had fled from Poland. The delegation asked Sugihara for assistance. As it was difficult to pronounce his name, the delegation called him “Sempo,” which was an easier name to pronounce, but had a similar meaning to Chiune.

As told by Dr. Zorach Warhaftig, who later served as Minister for Religious Affairs in the Israeli government, the meeting with Sugihara was a fateful encounter for thousands of stranded Jews, including many who represented whole schools of rabbinical seminaries (yeshivas), which were now stranded in Lithuania. The Jewish refugees sensed Lithuania would soon be overrun by Nazi Germany, and with the rise of antisemitic sentiments of the local population, some Jews felt it was time to look for a way to escape war-torn Europe. At that time, some yeshivas had moved to “independent” Lithuania in the hope of continuing their religious studies safely, after the Nazi and Soviet invasion of Poland. One such seminary was the Mir Yeshiva, still in existence today.

An escape possibility presented itself when two rabbinical students from The Netherlands, who were now stranded in Lithuania, learned that there was no visa requirement for entry into Curacao and Surinam, two Dutch-controlled islands in the Caribbean. The honorary Dutch consul, Jan Zwartendijk, had issued “entrance permits” for them. Taking advantage of this information, Dr. Warhaftig and his colleagues asked Zwartendijk if he would be willing to issue similar “entrance permits” for the Jewish refugees from Poland. He agreed. Once in possession of these “entrance permits”, all that remained was to procure transit visas for Japan.

The delegation requested Japanese transit visas, which would enable the Jewish refugees to travel through the Soviet Union and onward to Curacao and Surinam. The Soviet authorities were willing to issue transit visas through their territory only if the refugees could produce additional transit visas for countries bordering the USSR. The delegation thus spread out a map, and made the following undiplomatic, desperate request of Chiune Sugihara:

“You see, we have a visa to Curacao [..] We must reach Curacao via Japan and sail on a Japanese boat [..] Give us a transit visa to travel through Japan.”

Sugihara asked for time to obtain authorization from his superiors to grant the visas - an act that he saw as a purely humanitarian one. He felt he could not dismiss out of hand this plea by completely defenseless people. He promised to look into their request and immediately set himself to work. Recalling those dramatic times, Sugihara states:

“I really had a hard time, being unable to sleep for two nights. I thought as follows. I can issue transit visas…by virtue of my authority as consul. I cannot allow these people to die, people who have come to me for help with death staring them in the eyes. Whatever punishment may be imposed upon me (for disobeying government instructions), I know I should follow my conscience.”

The Japanese government refused to grant the authorization, however, and Sugihara decided to distribute the transit visas anyhow. The deadline for his forced departure from Kovno was fast approaching and Sugihara felt he had to act quickly if he was to be of help to the stranded Jewish refugees. He relates:

“Approximately, on August 10th, I decided there was no further point to continue negotiating with Tokyo. The following day I began on my own accord, with full responsibility on my part, to issue Japanese transit visas to the refugees without regard to whether so-and-so had the necessary documents or not.”

He requested a twenty-day extension of his stay in Kovno, when all other missions had left.

Between July 31-August 28, 1940, he distributed approximately 300 transit visas per day. Upon learning of Sugihara's insubordination, the Japanese Foreign Ministry requested him to cease and desist from issuing further visas.

"..but I fully disregarded these cables," Sugihara recalls, adding that he was acting strictly out of purely humanitarian considerations.

"I had no doubt that one day I would be fired from my work in the Foreign Ministry."

All the transit visas were written by hand. In those days, there were no computers. He stayed up night after night, day after day, forgoing meals, so that he could issue as many visas as possible. At times, his wife, Yukiko had to massage his aching fingers. When refugees began climbing the fence in order to enter the compound of the Japanese consulate, Sugihara came out and calmed them down. He promised them that as long as there was a single person left, he would not abandon them. Many Jews accompanied Sugihara and his family to the train station to bid him farewell. He was still issuing documents from the window of his train as it pulled out of the station. He gave the consul visa stamp to a refugee who was able to use it to save even more Jews.

Jews who received Sugihara’s transit visas were saved from the murderous hands of the Nazis, who invaded the Soviet Union, in June 1941. Included in the visas were those issued to more than 300 students and teachers of the Mir Yeshiva. This was the only case in which an entire seminary for Jewish religious studies was saved during the Holocaust.

At the end of the war, the Sugihara family was interned by the Russians in a Siberian prisoner of war camp for eighteen months. Upon returning to his country, Sugihara was dismissed from the Japanese Foreign Service, and earned a living doing odd jobs. Upon asking why he was being forced to resign, Sugihara was told that it was because of “that incident in Lithuania.” His career as a diplomat was over. After the war, answering questions about his actions, Sugihara replied:

“Those people told me the kind of horror they would have to face if they didn’t get away from the Nazis and I believed them. There was no place else for them to go. They trusted me. They recognized me as a legitimate functionary of the Japanese Ministry. If I had waited any longer, even if permission came, it might have been too late.”

One family, the Warhaftigs, was able to leave Kovno for the safe havens of Japan, China, the United States, and ultimately to Eretz Israel. (If students are interested to learn more information about this family and their contribution to the State of Israel see the "Additional Information for Teachers" section below).

On October 10, 1984, Yad Vashem awarded Mr. Chiune Sugihara the title of Righteous Among the Nations, for the part he played in the rescue of thousands of Jews in Kovno, Lithuania in 1940, whilst he was the Japanese Consul there at the beginning of WWII. His wife received the medal in Tokyo on his behalf, as he was by then bedridden. He died on July 31, 1986.

Note to Teachers:

As educators, our task is to instill in our students values, which will aid them to build a better and more tolerant society. We must sensitize students towards the other, viewing other human beings as themselves. Emphasize to students that Sugihara operated under extremely perilous conditions, at great risk to himself and his family. Although we cannot possibly compare Sugihara’s time to our own, we can nevertheless learn from his actions and convictions. Below are several questions that can be used for classroom discussion.

Questions:

In your answers for questions 1 and 2, refer to Sugihara’s own words as quoted in the text.

- Sugihara knew very little about Jewish people. He had much to lose by choosing to act as a rescuer. His decision put an end to his career and endangered himself and his family. What do you think motivated his actions?

- “A person who saves one life saves an entire world” - How does this Talmudic saying apply to Chiune Sugihara?

- What motivates some people to help others and what prevents others from doing so? Are these values innate or learned?

- If these values can be learned, how do you think we can teach people to view others as they see themselves?

Note to Teachers:

In their answers, encourage students to refer to direct quotes by Sugihara. As seen in the above text, he used expressions such as: "I cannot allow these people to die", "I know I should..", "If I had waited any longer..". He “listened” to his heart, and “felt” a sense of right and wrong. This is the language of the rescuer. Sugihara made little distinction between his own fate and that of the Jews appealing to him. As noted above, Sugihara continued issuing visas from his train window. He was able to see the Jewish refugees as individual human beings in comparison to many perpetrators during the Holocaust who viewed Jews as “cargo” or as “filth”.

Additional Information for Teachers

Doctor Zorach Warhaftig

Zorach Warhaftig was one of the signatories of Israel’s Declaration of Independence, in May 1948. In the last pages of his book, Refugee and Survivor, he writes:

“We tasted the full measure of suffering proverbially associated with the up building of Eretz Israel in mined Jerusalem and its besieged approaches. On one of my numerous journeys along the Jerusalem-Tel Aviv road, on the eve of Passover 1948, our convoy was subjected to a heavy attack from the Qastel Hill. But thanks to my resolution to cast my lot with the Yishuv at this historic juncture, I was privileged to be one of the signatories to Israel’s Scroll of Independence, thus standing with the galaxy of those who founded the renascent Jewish State. May this be a source of strength and pride to my descendants for generations to come.”

Mir Yeshiva

Mir, a town in the Belo Russian Soviet Socialist Republic, belonged in the interwar period to Poland, and was part of the Novogrudok district. Jews had lived there from the seventeenth century. The Mir yeshiva, founded in 1815, became one of the most famous Jewish institutions of higher learning. On the eve of World War II, the town’s Jewish population of 2,500 constituted about half the total. In September 1939 Mir was occupied by the Red Army and incorporated into the Soviet Union. The yeshiva, with its 500 students was moved to Vilna, Lithuania. (Encyclopedia of the Holocaust)

The Rescue of the Mir Yeshiva

In oral testimonies deposited at Yad Vashem, Rabbi Hayyim Szmulewicz, who succeeded Rabbi Finkel as the Rosh Yeshiva (Head) of Mir, and his wife Miriam, described the rescue of the Mir Yeshiva:

“When Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union, (they) were ordered to leave Kaidan, a district capital, and were split into four groups [..] They took steps to obtain exit permits from the Soviet Union for the Mir Yeshiva community. Several functionaries were in contact with Dr. Zorach Warhaftig, who headed the Palestine Office when Vilna belonged to independent Lithuania and who dealt with exit plans even after the Soviet annexation. Because of the illegal nature of the activities, only three members of the yeshiva were involved in all the arrangements [contacts with the Dutch consul, visa arrangements and other formalities]. [..] Before obtaining a Soviet exit permit, all had to appear in person before the Soviet secret police, whose screening seemed to be a mere formality [..] The applications for exit permits were approved by the NKVD offices in Vilna and Kaunas (Kovno). Despite the relatively liberal attitude, several dozen yeshiva students were nevertheless detained and failed to gain exit permits. These included former Polish citizens who had opted for Lithuanian citizenship. No survivors have been found among those Mir yeshiva students who failed to leave at that time. The Germans and their henchmen no doubt murdered them."

A historical timeline of related events

- August 23, 1939: Ribbentrop/Molotov non-aggression agreement signed between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

- September 1, 1939: Nazi Germany invaded Poland, thus beginning World War II

- September 3, 1939: Britain, France, India, Australia and New Zealand declare war on Nazi Germany

- September 17, 1939: The Soviets annex Poland as part of the Ribbentrop/Molotov agreement

- June 15, 1940: The Soviet Union annexes Lithuania, which until then was an independent state. This was part of the Ribbentrop/Molotov agreement

- July, 1940: All foreign representatives in Kovno, are instructed to close their legations, on orders of the new Soviet authorities, endangering the escape of many Jewish refugees who had already fled from Nazi occupied Poland to Lithuania and were planning to leave for other European or Asian destinations

- June 22, 1941: Nazi Germany invades the Soviet Union

- June 24, 1941: Kovno occupied by Nazi forces

Suggested Readings:

- Hillel Levine, In Search of Sugihara: The Elusive Japanese Diplomat Who Risked His Life to Rescue 10,000 Jews from the Holocaust. The Free Press/Simon & Schuster. New York, 1996

- Zorach Warhaftig, Refugee and Survivor, Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust: Yad Vashem & Torah Education Department of the World Zionist Organization. Jerusalem, 1988.

- Efraim Zuroff, The Response of Orthodox Jewry in the United States to the Holocaust, The Activities of the Vaad-Ha-Hatzala Rescue Committee 1939-45 Yeshiva University Press. New York, 2000.

Suggested Film:

- Zorach Warhaftig, Survivor and Refugee of the Holocaust 1996