Intended for high-school students

Activity duration: approx. 90 min.

"Witnesses and Education" is a unique project featuring educational autobiographical journey films of Holocaust survivors. In these films the survivors recount their personal stories, filmed in the actual locations where the events transpired. The films follow their journey from the locations where they experienced the horrors of the Holocaust to the locations where they found the strength to resume their life afterwards.

While watching the films we are exposed, among other subjects, to the spirit of Jewish solidarity, which characterized the life in Jewish communities before, during, and after the Holocaust. The mutual care and sense of responsibility was an anchor of compassion, sanity, and sometimes even survival for the victims. However, sometime the individual had the upper hand over the togetherness during the struggle for survival, prompting questions and moral dilemmas. In the course of this lesson we wish to accompany the witnesses, the subjects of these films, from this point of view, and supply the students with further perspective in the study of the Holocaust.

Lesson objectives

- Acquaintance with the witnesses and their personal story

- Devoting attention to values such as mutual Jewish assistance and responsibility along the witnesses' journey from their birth to their liberation, using individual stories which together form a part of a human, Jewish, fabric that wished to hold on to life and its meaning during one of human society's bleakest and darkest periods.

- An attempt to understand the meaning of 'togetherness' during a period of disintegration of the Jewish community and the family in its midst. These concepts will be examined non-judgmentally, with awareness that the issue of "togetherness" was often an unbearable burden for the individual, particularly in a reality of extermination.

To the Teacher:

In this lesson you will find various subjects for discussion about individuality and togetherness during the Holocaust. We recommend choosing several subjects relating to each period to allow for a serious and thorough discussion. In each part the subject is highlighted in color to make the choice easier. In order to facilitate the teacher we added, in several instances, a concise answer along with the questions for discussion.

Historical background about the terms "individual" and "togetherness" in the Jewish world:

Prior to viewing the films, the terms "individual" and "togetherness" should be examined in the context of the Jewish community. It seems that as much as Judaism was concerned with the protection of the community and the public, it also wished to protect the individual's position within the public. During the centuries in which the traditional community existed, from the beginning of the exile until the latter part of the middle ages, the Jewish public preserved its belief system and way of life in order to protect its existence. Beyond the observance of commandments (mitzvas) and the conduct of public Jewish rituals (such as prayer), the Jewish community maintained public institutions serviced by officials who provided for the community and protected its integrity, from Communal baths, (Mikveh) burial societies (Hevra kadishah), loan institutions (Gemach) and broader institutions (Council of Four Lands), to the community Rabbi, the tribunal, the circumciser (Mohel) and the teacher (Melamed). However, the position of the individual was also strictly guarded and protected by social, economic and religious laws.

Even after the disintegration of the traditional community these institutions continued to exist, although they involved: The Melamed was replaced by the Chedder (Torah study classroom) and later by schools, and in place of the "Council of Four Lands" new international institutions such as the "Alliance israélite universelle" and the Jewish Joint were created. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that during the Age of Enlightenment the emphasis was on the individual and his needs. These processes also influenced Jewish society, a fact that brought about the establishment of cultural, social and political movements. The Jewish society became gradually more pluralistic and democratic, and allowed for more various ideological trends, pertaining to the individual's choice regarding his way of life. However, the mutual Jewish responsibility remained and found a more modern expression in, among others, political parties, social organizations and in Jewish education and community institutions.

Part 1: Jewish Mutual Assistance before the Holocaust – "They are Jewish Too"

In her film "She Was There and She Told Me“, Hannah Bar Yesha, a survivor from Hungary, refers to the Jewish diversity that existed in Hungary. As a member of an orthodox family, she visited the Neolog synagogue in Budapest with her parents during a holiday vacation. Her father saw this visit as an important lesson for his daughter, a way to experience the diversity of ideologies and worldviews.

In the film "My Lodz No Longer Exists", Joseph Neuhaus leads us, the viewers, to the landscapes of his childhood, to the streets in the Jewish area of Lodz. One third of the Lodz population was Jewish. Jews from all different streams often immigrated to larger cities during the earlier stages of their development, due to the economic potential inherent there. This process was typical of Jews in general, and therefore their proportion of the population in large cities was often high. Thus also in Warsaw, the capital of Poland, Jews comprised one third of the population. In the cities, Jews continued to lead a communal life, as Joseph describes. He explains that the Jewish community was made up of different groups, and that there was room for all of them.

Contrastingly, Ovadia Baruch was born in Thessaloniki, and was a member of a warm and nurturing Mediterranean Jewish community. At some point, Thessaloniki was regarded as a Jewish city since most of its residents were Jewish. Many of the Jews in Thessaloniki worked in different branches of the city's port, and for many years it remained closed on Saturdays (Shabbat) due to its Jewish nature. In his film, "May Your Memory be Love" the direct connection between Ovadia, the son of a simple worker, and the community Rabbi is mentioned. In addition, Ovadia's disposition towards love and giving are apparent from childhood, and is expressed in the care and concern he displayed toward those around him - family members and others.

The story of Avraham Aviel is unusual. He was born in Belarus in a small agriculture village called Dowgalishok, inhabited by twelve families, nine of them Jewish. This way of life was relatively rare and not representative of Jews living at that time in Europe. The family's children were sent to study in a Cheder (Jewish religious primary school) and a small Yeshiva (Jewish secondary school) in the near town of Radun, the town where Rabbi Israel Meir (HaKohen) Kagan, known as the Chofetz Chaim, based his congregation. The living fabric of Jewish life in the rural regions is revealed throughout the film "...But Who Could I Pray For?" which shows the mutual responsibility that existed between the large and the small communities, and in some cases between those and individual families that lived in the area.

Fanny and Betty, two sisters from the Ichenhauser family, were born in Frankfurt, Germany, and after the rise of the Nazis to power immigrated to Amsterdam, Holland. In their shared film "From Where Shall My Help Come?" the sisters recount growing up in the city, and their involvement in the Zionist youth movement, which alleviated the trauma of immigration and became a social and emotional anchor for them. In the movement the two found friends, youth experiences and ideals. It should be noted that at the time youth movements flourished in Europe, and represented the different political factions that co-existed in Judaism.

Questions for discussion:

- How was the mutual Jewish responsibility expressed before the Holocaust? How is it expressed in each one of the passages?

- What is the power and the role of Jewish solidarity within the individual's life in the community?

After the Nazi occupation the condition of the Jewish community and its institutions deteriorated. The Jews had to adapt to life under violent occupation and terror, and continue their lives under of the restrictions and anti-Jewish climate. The beginning of the crisis and the process of deterioration shadowed the Jewish public during the Holocaust. In his film "From Generation to Generation" Yisrael Aviram describes the transition from normative life to life under German occupation, and the attempt to preserve the life of the Jewish community and public prayers in the houses of Jews in his city, Lodz, despite the restriction and the atmosphere of terror prior to the establishment of the city ghetto.

Part 2: Individuality and Togetherness During the Holocaust – "We were fortunate that we were a family..."

The period of Nazi occupation, including the world of the ghettos, was characterized by the attempts to preserve the "togetherness" despite the Nazi policy which intended to crumble Jewish solidarity. It seems that the scope of this "togetherness" diminished as the terror became more and more aggressive, but despite the difficulty, the Jewish institutions continued to operate in a limited capacity as long as it was possible. These attempts included impromptu synagogues, concealed education institutions, youth movements that were obligated to their participants, and the maintenance of culture and recreation in the form of group activities, theaters and the like. These institutions frequently changed their form and character due to the circumstances, and were spontaneously reestablished.

Once the ghettos were established in the city, the Jews were transferred into them. Later were joined by Jews from the neighboring towns and villages. And so, Avraham Aviel's family was forced to move to the ghetto established in the city of Radun, near the village Dowgalishok. Avraham describes the difficulty of the departure from the familiar, as well as the distress that prevailed at the joint living quarters of several families crammed into one house. In parallel he also emphasizes the evident mutual assistance in the ghetto.

Questions for discussion:

- From Aviel's testimony we can learn about several manifestations of help and the responsibility of the public towards the individual in the ghetto. What are they? What is unique about each one? (Judenrat – in charge of finding homes as part of its duty , as opposed the public kitchen – spontaneous communal aid )

Alongside the official leadership in the ghettos, the Judenrat, there was also an unofficial leadership, manifested, among other ways, in the youth movements. In the large ghettos many youth movements operated, representing the different political parties that continued to exist, although in a diminished format, inside the ghettos. The youth movements restored their branches, opened their gates to new members, maintained communication with the branches in the different ghettos, and on occasions provided the education structure that filled the gap after the schools were closed. In Yisrael Aviram testimony, the importance of the youth movement in his life as a boy growing-up in the ghetto is revealed, as well as the care the movement showed when one of its members was in distress.

In many of the ghettos hunger, diseases and epidemics were common. Yosef Neuhaus recounts the hunger his family experienced, the attempt to endure this reality, and the social life that existed in the ghetto despite the hunger.

Questions for discussion:

- Why does Yosef Neuhaus assert that "luckily, they were a family"? (The 'togetherness' still remained within the family structure.)

- What can be learned from the first frame about the Judenrat's responsibility in the Lodz ghetto? (The concept of work.)

- The significance of receiving a gift in the ghetto should be noted - giving a gift, even one that seems trivial, for one's birthday, has an element of sacrifice (one's portion of bread in the ghetto is far from insignificant.)

Subsequently, in Yosef Neuhaus' testimonial journey he articulates many times the role of the family in the ghetto. It seems that the family 'togetherness' was of great significance to the individual, due to the family's ability to protect the individual and alleviate the hardship of life in the ghetto (for example the hunger, especially when one is first confronted with exile into the unknown). In this testimony what can be noted is how the community's 'togetherness' was disintegrated because of the need to protect personal family members.

Questions for discussion:

- What are the ways in which the family is significant for the individual in this testimony? (Beyond showing concern for the family during the expulsions, Avraham Aviel recounts the mother's attempt to alleviate the distress by frying potato peel pancakes.)

Avraham Aviel recounts the moment of returning home after the German's round-up operation (Akzia) in which his mother and little brother were killed. Since Radun was part of the Soviet-Union at the time, the Jews were shot nearby. Avraham, who saw his big brother marching with a group of workers out of the death, pits area, hurried to join him and return to the ghetto, risking his life. In his testimony he recounts the desolation left in the ghetto after the murder of its inhabitants. However, there is a sense of 'togetherness' between the brothers, as well as in the wish to join other Jews who escaped to the forests to survive.

Part 3: Aloneness During the Escape and While in Hiding – “It seemed to me as though it was my entire life…"

Sometimes the decision whether to escape or to stay in hiding fractured the nuclear family. The nature of hiding often required separation of the family members due to the difficulty of hiding entire families, or due to dangers that might have arisen during the escape of groups. Sometimes a hiding place was found only for young children and toddlers, but at other times the children were in fact those who proved to be an obstacle for the rest of the family, and thus, a painful separation was required. These separations harbored unbearable pain and at times were accompanied by many feelings of guilt.

Among the witnesses documented in these filmed journeys there were those who found shelter at their neighbors' homes, the local residents, who risked their lives and put themselves in danger in order to protect them. Some of them found refuge in the city, some in the country, while some found shelter in the woodlands, joining partisan units.

While Fanny and her husband found a foster family for their toddler, Uri, and they themselves were hiding with a family in the village, Betty was left with her elderly mother. After Fanny suggested that the two should join them, Betty decided to turn down the offer, if only because she wished not to leave her mother alone. It was a fateful decision that affected both their lives.

In contrast to the story of the sisters, Avraham Aviel joined the partisans and was able to survive the daily struggle in the forest. Earlier, the brothers met with their father after the other members of the family were murdered. The father taught his sons how to acquire food; however, he decided that they should separate.

Questions for discussion:

- What is the process that the Jewish family underwent while being forced to hide in fear of death? What can we learn about the balance between individuality and togetherness during that period?

After her mother and sister were murdered, Malka Rosenthal and her father were left on their own. In her film, "The Heavens Will Open for You" the escape route of the father and his daughter is recounted, how they lived in the woods for a while, and how they searched for improvised hiding places. Eventually, the father joined the partisans and left Malka with the Kot family, a family of farmers, who risked their lives and did all they can to keep Malka alive. Malka lived alone in a barrel in the cowshed for a year and a half, until she was let out for fear for her life.

Questions for discussion:

- How did Malka survive alone in hiding? (Imagination and clinging to her former life in they hope it will be resumed.)

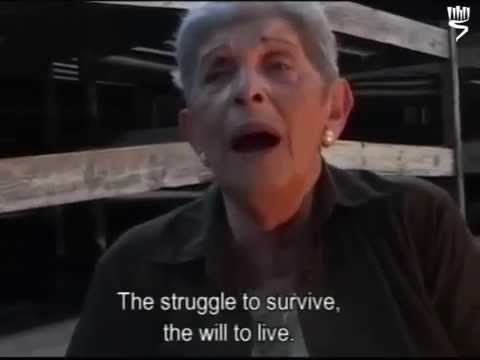

Part 4: The Camps: "The struggle for the moment, [..] to survive, the will to live…"

The expulsion to the camps marked the start of the individual's horrible and tragic breakdown. Family members were torn from each other at the camp selections and for the most part remained alone. In cases where they remained together, they were often separated during their stay in the camp, either because of its nature, or due to the high mortality rate. Much has been written about the prisoner's struggle in the camp, the conditions, the hunger and diseases, the hard labor and the torture of body and spirit. In this chapter we wish to reveal the other story, find the expression of humanity, what little amount solidarity that could still be shown in the camp, despite the darkness and the evil that were present everywhere. These stories are doubly compelling. It is not a trivial thing for a prisoner to lend a helping hand or share warmth with a fellow inmate in the reality of the concentration and extermination camps.

The horror started with the expulsion to the camps in very densely crowded train cars, intended for livestock. These voyages sometimes lasted days and even weeks without minimal living conditions. Some did not survive the journey. Yisrael Aviram was transferred from the Lodz ghetto along with the rest of his family. Upon entering the train car he encountered two girls who were pupils in the youth movement. In the horrid conditions in the train car Yisrael didn't forget his role and his duty as a youth movement guide towards the two.

Questions for discussion:

- What can we learn from Yisrael Aviram's conduct in the train car? (The ethical values of the youth movement endured even under extreme conditions)

While her sister and family stayed in hiding, as mentioned earlier, Betty and her mother were sent to the Westerbork transition camp in Holland. Betty, a professional nurse, worked at the camp in a shed used as an infirmary. Betty took upon herself a considerably dangerous role and practically risked her life for her fellow inmates. During the filming, Betty remembered her birthday which was celebrated in the camp, and the gift she was given when she became 20 years old.

Hannah Bar Yesha was sent to Auschwitz with her mother. She recounts the way of life in the women's camp at Birkenau after a day of hard labor.

Questions for discussion:

- What did the female prisoners hold on to in order to survive the camp? (Relying on memories from the past, maintaining normative human relationships in a world that has collapsed.)

As in Hannah's story, Ovadia Baruch also testifies to the solidarity that existed between the Greek prisoners in Auschwitz. This group was known for the mutual assistance of its members as well as for the trading abilities of its members. These qualities were crucial in the camp environment, and could in some cases actually allowed some of the prisoners to survive. Ovadia recounts how he got a good job at the camp after a friend from Thessaloniki managed to get him work in one of the factories.

Subsequently, one of the dilemmas in the camps was: what are the limits of the 'togetherness'? How does one act when the concern for oneself or for one's friends comes at the expense of other prisoners? Dilemmas such as these arose time and again in the everyday life in the camp, and as time passed they became more complex and weighty. Part of the tragedy of the human existence in the environment of the camp was that the margin of choice when confronting those dilemmas was narrowed to the basic biological instinct of existence – the survival. The physical survival governed the prisoner in the camp and dictated his actions and decisions. Ovadia Baruch's story is exceptional since it transcends the boundaries of mere physical existence in the context of the camp.

Toward the end of the war the "death march" method of extermination was developed. Hundred of prisoners were forced to march thousands of kilometers to concentration camps within the borders of Germany. A large percentage of the prisoners died during the march by gunshot, starvation and exhaustion. Yosef Neuhaus, who was in the camp with his father, recounts the death march to the Ravensbrück camp. Despite his deteriorated physical condition, Yosef insisted on carrying his father for weeks rather than see him collapse.

Questions for discussion:

- What was the significance of spiritual and cultural life in a reality of de-humanization?

- What was the significance of 'togetherness' for the individual living in the camps?

- What can be learned about the way in which Ovadia describes his love affair with Aliza? (spiritual transcendence, strength, a tool for survival, exceptionality)

- How can Yosef Neuhaus' devotion to his father during the grueling death march be explained?

Part 5: Liberation and Return to Life – "I felt that I was truly alone"

After the liberation many of the survivors found themselves alone, without family members, without a community, without property and without a home. They had to restart their lives, search for their relatives, return to the empty houses and decide where they were heading. There were those who were able to find relatives and friends through lists that were published anywhere Jews congregated, and naturally, these reunions were extremely emotional. But in many cases the survivors had to reconstruct their lives on their own and start from scratch, haunted by their traumatic past.

Upon liberation Avraham Aviel returned to Radun to try and locate the few survivors from the community. These were terrible times, and the few survivors gathered for the Yom Kippur (Jewish High Holidays) prayer. Avraham recounts the moving prayer and his personal distress while acting as cantor, leading the prayer.

Hannah Bar Yesha was only 13 years old when she was liberated. During the filming she recalled the moment it struck her that she was alone in the world. She recounts the moment of realizing that she was alone and responsibility toward her future. She had to decide which way to go and where to resume her life.

After returning to Lodz in a failed attempt to search for family members, Yisrael Aviram and his father arrived in Germany on their way to Israel. The two weren’t discouraged and eventually found Yisael's sister Henia, on the relative list. The reunion of Yisrael and his sister was shared with other survivors who wished to take part.

After reaching Israel, Yosef Neuhaus was recruited to the Israeli Palmach – the underground army during the period of the British Mandate – and fought in the 1948 Israeli War of Independence. Yosef recounts his obligation toward his fellow soldiers, and his dedication to his duty as a medic.

Questions for discussion:

- In Yisrael Aviram's testimony it seems that the boundaries between 'individual' and 'togetherness' were blurred after the liberation. Discuss. (The aloneness of the individual leading to locating of family members, as well as to the creation of alternative families, and even to sharing intimate moments, seemingly familial, with strangers ; mass marriage ceremonies in the displaced persons camps)

- Considering the struggles that we have seen to stay together, how did the survivors cope with the void created by the Holocaust?

Conclusion

As we have seen, after remaining on their own, many survivors began to restore their lives, searched for relatives, found new life partners and raised families. Those Individuals created a new kind of 'togetherness', while for most of them the pre-war 'togetherness' would remain a memory. Many of them engaged in commemorating that 'togetherness' which was lost – their community and families. In their new life they wished to establish new families and communities, but it can be said that the longing for that lost 'togetherness' gave many of them the strength to fight for a cause that transcended the boundaries of family and community across to the public realm of the Jewish people.