Two Rings is Millie Werber's personal and heart-wrenching memoir of her remarkable experiences surviving the Holocaust, as written in collaboration with Eve Keller.

"At the heart of this magnetic memoir lies something utterly unexpected: a story of a love that blazed briefly in one of the darkest corners of occupied Poland.

Born in central Poland in the town of Radom, she [Millie] found herself, at fourteen confined in a ghetto in 1941, a slave laborer in an armaments factory in the summer of 1942, and transported to Auschwitz in the summer of 1944, before being marched to a second armaments factory. She faced death many times; indeed, she was certain that she would not survive. But she did. Many years later, when Millie began to share her past with Eve Keller, the two women rediscovered the world of the teenage girl Millie had been during the war. In gripping detail, Millie and Eve recreate the events and emotions of Millie's remarkable, wartime survival. They also reveal Millie's most precious, private memory: of a Jewish policeman to whom Millie was secretly married for a few brief months. He died leaving Millie with a single photograph and two rings of gold that affirm a great and abiding love in the bleakest imaginable time."

This study guide includes some excerpts from the book Two Rings, with which you can work with your students, and around which you can ask relevant questions in relation to some of the experiences that Millie faced during the Holocaust.

Throughout the Holocaust people were faced with impossible situations, choiceless choices and dilemmas on a daily basis. Millie's story deals with these topics and with others. Her account can therefore enable us to gain an important personal perspective on these crucial issues. In this study guide, we include some excerpts from the book that illustrate some of these difficult situations, such as hunger, work, separation, and others. We provide you with tools to analyze them. We suggest holding discussions with the students around these topics. These can initially be held in groups which can be followed by whole-class discussions. During these discussions try to elucidate the meaning of the situations Millie found herself in:

- Which, and if, there were choices she could make?

- What can we learn from those choices about Millie, about human beings, and about that period of time?

- The Holocaust should be regarded not only as a historical narrative, but also as a human story. We believe that teaching about the Holocaust should be based on questions that will allow us to focus on the lives of the Jewish victims before and during the Holocaust. We believe that the aim of the educator must be to "see" the victim as an individual rather than as a statistic, and to communicate this idea to students. Doing so allows for empathy with the victims, as they become real people with human identities and aspirations. The empathy created allows students and teachers to discuss the Holocaust more meaningfully, as students can relate more easily to human beings than to two-dimensional, black-and-white pictures or numbers in a list. Once empathy is created, educators can tailor their lessons to the emotional and cognitive level of the students. We recommend to use the book Two Rings, with students aged 17 and older.

- When we approach the story of the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, our study should be divided into three topics:

- Jewish life before the war;

- The everyday life of Jews during the Holocaust: how did Jews live in the face of dehumanization? What were the moral dilemmas they were forced to face? What choices did they have in a world where each choice led to an untenable situation?

- The return to life of the survivors after the war.

- When studying about the Holocaust we need to focus on the fate of the Jewish victim during the Holocaust; we need to shift the focus from discussing death to discussing life. This discourse can allow a discussion about the subjects of coping, the human spirit and human morality.

Undoubtedly, death was ever-present in the life of the Jews as we see it over and over again as we read Two Rings, and the events Millie experienced and witnessed.

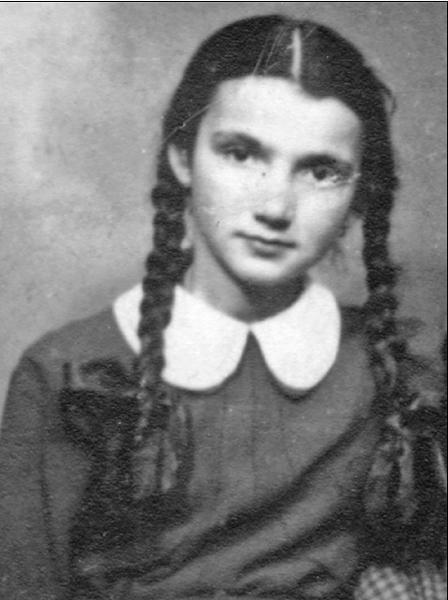

Millie in 2012

During the Holocaust, in a world in which moral questions could not seemingly be resolved, there was still a place for dilemmas despite the limited choice - dilemmas in which every choice challenged normal moral standards; dilemmas which could result in either life or death.

Facing up to a choice between two values shows the wish to preserve human norms. Therefore, the educational aspect of the dilemma is not in its solution, but rather in the fact that the dilemma is acknowledged. We hope to observe, study and relate to the choices made by Millie and by surrounding individuals who played a role in her life.

After sharing with her readers all of the horrors she had gone through, Millie chooses to focus on the good in people, on the rays of light she found in all the darkness and evil that prevailed during the Holocaust. She expresses her desire to thank the people that helped her "not to lose hope and belief in human beings". In the epilogue of her book she writes,

"I do believe in people: I believe that even in the most horrendous circumstances, there is still space for choice. No matter what the situation, people still get to determine how they will be in the world—whether good or evil, kind or cruel, or anything in between—through daily acts of choice, both large and small. Mima and Feter, Zwirek and Zosia, and all the rest of them— they made choices that helped me live when so many others did not."

This quote can lead to a discussion on the existence of choices during the Holocaust and what they meant.

- Do you believe people had the freedom to make choices during that era?

To add to the discussion you can also reference Viktor Frankl's book, Man’s Search for Meaning. In his book, Frankl, who was a psychologist and Holocaust survivor, wrote:

"Man can preserve a vestige of spiritual freedom, of independence of mind, even in such terrible conditions of psychic and physical stress.

We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms - to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one's own way. And there were always choices to make. Every day, every hour, offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your very self, your inner freedom; which determined whether or not you would become the plaything of circumstance, renouncing freedom and dignity to become molded into the form of the typical inmate."1

- Documents on the Holocaust, Selected Sources on the Destruction of the Jews of Germany and Austria, Poland and the Soviet Union, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, 1981, Document no. 73.

Another subject around which you can lead a discussion is that of hunger.

This was one of the greatest hardships the Jews had to face during the Holocaust. The severe food shortage in ghettos and transit and concentration camps led to an almost impossible challenge.

- How did people function in a state of starvation?

From the ghetto, Millie was sent to live and work at a factory. She describes the hunger she encountered there:

"At first, I didn't eat. I had never been much of an eater, anyway... But Hitler taught me to eat; that's what I say now. In the ghetto, meat didn't exist. We lived on bread – we were allotted one hundred grams per person per day – and occasionally a potato if someone was able to get one. At the factory, we were fed twice a day, once before our first six-hour shift, and once after our second. In the mornings, we got what they called coffee – though no one thought what we drank actually had any coffee in it – along with a slice of brown bread. After our twelve hours of work, there was a watery soup of some kind that sometimes had little bits of meat floating in it.

I was hungry at the factory, hungry in a way I hadn't known in the ghetto."

The struggle for life also entailed harsh moral dilemmas. The extreme lack of food meant that acquiring supplementary food was vital for one's survival. This in turn meant that people were forced to face dilemmas such as:

- Should they send their children to get some food knowing their child could be caught?

- Should they steal from their neighbor?

Alongside these dilemmas, religious and observant Jews were faced with additional dilemmas in regard to food and hunger. These dilemmas arose when following the Halacha (Jewish religious law) became impossible.

- An example of this can be found in Millie's story: Should she eat the soup that was served to her in the factory knowing that it was not kosher or should she choose to not eat at all?

"...But even though the hollow pull of hunger never left me, I knew I couldn't eat this soup. The soup was unkosher, it was traif. My family hadn't been especially religious – my father didn't wear a beard, and neither he nor my brother went to synagogue on Shabbos – but we followed all the observances of Jewish ritual, just as everyone around us did: We didn't work on Shabbos, the women kept their arms and legs covered, and, of course, we kept kosher. There was never a question about these things; it was how we lived and how our families had lived for as long as we knew. This soup at the factory was traif, and I knew for a certainty that if I would put it to my lips, I would choke."

In Judaism, human life is essential and so pikuach nefesh, the obligation to save a life in jeopardy, including one's own, is considered a major value to uphold. According to this principle, non-kosher food may be eaten when kosher food becomes unattainable and a person is faced with starvation. Nevertheless, it was a dilemma for many Jews during the Holocaust, and some chose to avoid eating non-kosher foods.

On the other hand some Jews, even if they were religious, decided to eat non-kosher foods, as they knew this was probably the only way they would survive.

You can use this example to create a discussion on the choiceless choices people were faced with and the dilemmas they encountered as well as on the way each chose to deal with them.

An example of another dilemma is that of Mima, Millie's aunt, who was with Millie throughout most of the ordeal and who had taken the place of her guardian,

"It was during the appels, too, that women were chosen for transport. Everyone wanted to go. We didn't know where the chosen women would be taken- we were told to factories to make guns – but any place was better than this; to be taken for a transport was a ticket out of hell.

Here, too, Mima was always thinking about me. Twice she was chosen for a transport; twice she had the chance to leave.

But each time, she positioned herself at the back of the gathering group, and when she saw that I was not part of the transport, she slipped away and stayed behind. To be with me. To lend me her shoe for a pillow. To redden my cheeks with a bit of brick. To take care of me."

- What were the decisions that Mima had to face?

The Holocaust challenged established social norms, values and relationships. In a reality in which each individual Jew was subject to persecution and the threat of destruction, the instinctual drive for physical survival became dominant. However, even in such conditions, Mima risked her life to save Millie, to stay with her, to take care of her. More than once she forfeited a chance to escape in order to help Millie.

Another topic for discussion can be separation. One of the greatest hardships families faced during the Holocaust was separation from one another. In many occasions parents had to make choices in a situation where they virtually had none and where they didn't have enough information on what was happening around them. In most cases they could only trust their instincts.

- How does a mother part from her children?

- How does she decide that her decision is the best one for the child and maybe also for herself?

In Millie's case, while still living in the ghetto, Feter, her uncle, tells the members of the family that work might save them. Millie finds a work in the factory outside the ghetto, but her mother doesn't. She encourages Millie to leave the ghetto and go and work in the factory. She chooses separation and decides to believe that work will really save her daughter's life.

- How do you think a mother who has to send her children away feels?

During the struggle for survival in the ghettos, mothers were forced to make decisions that contradicted their role and went against their instincts. The delicate fabric of family relationships was stretched to the breaking point and often torn.

In the following paragraph Millie refers to the time when she was still living a "normal life" before the Holocaust, in her own house with her mother. She describes the sleeping arrangements in their house.

"Mama and I shared a bed. Before we moved to the ghetto, we lived in a large, two room apartment in the center of Radom, near City Hall, on Wolnosc Street. The second of the two rooms was separated across the middle by two large wooden wardrobe cabinets in which Mama kept her sewing materials. In the back section of the room were two beds, one for my father and brother and one for Mama and me. My father lived in Paris for the first seven years of my life – I think he felt it would be easier to make a living there than in Poland – but even when he came home in 1935, he slept with my brother, and Mama with me. I loved being in bed with Mama, nestling in her warmth at night under the feather blanket".

Further in the book, she mentions this again,

"But Mama and I needed work, and even though she was over forty, Mama said she would go with me to the munitions factory to register.

It didn’t take long for the Germans to sort through the many people who showed up. I was accepted without question; I was young, thin, and delicate, but in apparent good health. At forty-three, Mama was too old. They wouldn’t take her. She was sent back to the ghetto, and I was left at the factory, alone.

I wanted desperately to go with her, to return to the ghetto and stay with her and the rest of our little family. I wanted to be able to sleep beside her, to feel her warmth surround me. Always that, maybe mostly that—the warmth of Mama’s ample body in the night. Despite the oblavas, the unprovoked brutalities, the sickness and the hunger and the dread that were upon me, still, I wanted only to be with Mama in the ghetto. Yet I was not allowed. I was made to stay at the factory. Feter said, and the family agreed, if you work, you might live. So, at fifteen, I began to work in the ammunitions factory, and after that first day at work, I never spent another night with my mother again."

- What do you think that sharing a bed with her mother meant to Millie?

- What do you think is the meaning of "I never spent another night with my mother again"?

For Millie this is the moment of separation from her family, the loss of it, the end of her known world, and her security.

The concept of work took a completely different meaning during the Holocaust, this is expressed in the two following excerpts from Millie's book. One discusses work before the Holocaust and the second one deals with Millie's "work" experiences during the Holocaust.

Before the Holocaust:

"Mama wanted me to learn to sew so that I would have a trade. Sewing and embroidery were the two professions acceptable for girls. Mama was successful in her business – she kept us housed and fed - but it seemed to me that she worked all the time, until we lit the candles on Friday night and then again as soon as Shabbos was over. When my father lived away, it was Mama who supported me and my brother. My father did send home some money, I think, and I know he sent occasional treats - canned sliced pineapple, for example, which I happily devoured between pieces of buttered cornbread – but it was my mother's sewing business that kept our household together. I was young –barely a teenager – and Mama wanted to teach me, too. Perhaps she had a sense that a woman needed to learn to provide for herself, in case she had no one else to rely on.

... I didn't want to work, but work is what saved me in the war."

During the Holocaust:

"The days in the factory quickly became routine. I worked twelve hours in the machines, I was fed twice a day, I had a shower maybe once a month. We didn't think much of what we were doing; certainly we didn't talk about it. We were, after all, working in an armaments factory, helping our enemies, helping to make the very munitions that were being used against us. We just did our work. We did what we were told to. We were trying to survive."

- What do you think was the function of work during the Holocaust?

- Do you think we can call it "work"?

- What was the alternative to "work"?

The phrase Arbeit macht frei appears over the entrance gates to Auschwitz, and to other camps as well. You can create a discussion about what each student thinks the true meaning of this phrase was. To add to this discussion you can reference Primo Levi's understanding of this phrase:

"These are the well-known words written over the entrance gate of the Auschwitz concentration camp. Their literal meaning is ‘work makes free’, but their real meaning is somewhat less clear; it inevitably leaves us puzzled, and is worth some consideration...‘Work makes free’ ... take on a precise and sinister meaning. They are, in their turn, an anticipation of the new tablets of the Law, dictated by master to slave, and valid only for the slave."

2

- Primo Levi, Arbeit macht frei, Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi, accessed on December 27th, 2015.

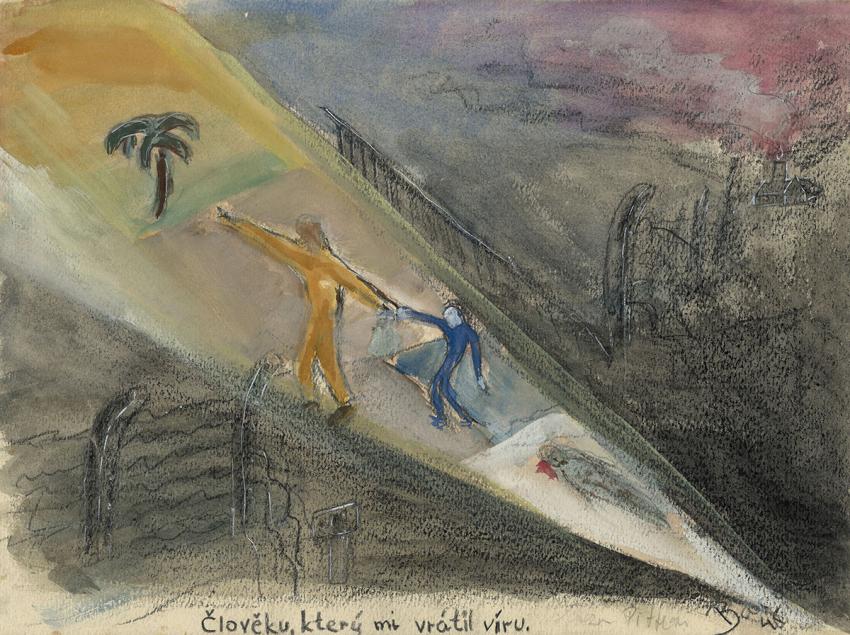

Yehuda Bacon (b.1929), To the Man who Restored my Belief in Humanity Prague, 1945

In a world where murder had become the norm and brute force begat acts of unprecedented horror, many were unable to do more than struggle for mere survival. Yet, simultaneously, some were able to behave differently, and demonstrated astonishing spiritual strength during a time of persecution and death. Facing the disintegration of entire fabrics of life, they clung to the essence of existence and attempted to preserve life grounded in moral values, as well as a cultural dimension befitting a decent society.

Throughout her story, Millie describes the acts of goodness that were shown toward her. In retrospect, Millie feels that these acts saved her life. Some examples are:

"Once, after I had fainted, a woman I knew slightly from the Radom factory – she was a twin, and she had been experimented on by Mengele – saw me on the ground and came over to me and offered me a little piece of raw potato she had. It was to help me wake up, she said. This matters, I think – that such kindness was possible, even in Auschwitz. If a guard saw me fainting during an appel, however, I would certainly be punished, and if a selection were to occur and someone saw the paleness of my face, I might get taken away to be gassed."

The following excerpt serves as another example of these "acts of goodness":

"Soon after the Yom Kippur “sacrifice,” I had my own encounter with death...

...Zwirek, the Pole who supervised the celownik, came up to me one evening as I started to work at my machine...

'You know,' he said, 'all the fifteen hundred pieces that you made last night—they are no good. Every one you put in the box is wrong.'

Out of the fifteen hundred pieces I was required to drill each shift, I was allowed maybe two or three that weren’t right. The rest had to be precise, perfect.

'What happened?' he asked. 'You know what’s going to be done. You know what this means...'

...It was a death sentence...I knew precisely what it meant: It meant my execution...

...He said quietly, 'I cannot let you die. I cannot let you die. But I don’t know what there is to do.' And then he left...

...Later that night, Zwirek came back and took me aside. I remember I had to bend my neck all the way back to look up at him standing over me.

'I will take these boxes,' he said, softly, almost tenderly, 'and I will bring them back to my office. And for every box that you finish, I will take out some good ones and put back in some of these bad ones. And I will substitute these for those until all the mistakes are gone. But you mustn’t make any more mistakes. The rest have to be perfect.'

Then, without waiting for a reply, he left, and he never spoke to me again.

For nothing, a man was killed; for nothing, my life was saved.

Zwirek was a Pole; I was a Jew. That is important."

- Why do you think that the fact that Zwirek was a Pole is important to Millie?

- Millie writes that these acts contributed to her survival. In which ways do you think they did so?

For Millie it is extremely important to remember the people that did help her, no matter their religion or nationality. She is thankful that in all the darkness and with all the evil that surrounded her, there still were good people.

You can use the following examples to hold a discussion about what these acts, large or small, in the shape of a piece of bread, a lie, or a helping hand meant.

Yehuda Bacon created in 1945 in Prague, an artwork called To the man that restored my belief in humanity. It is dedicated to the educator Pitter Přemysl.

In this artwork, Bacon refers to the rehabilitation process he underwent as a survivor after the war: from a major crisis of faith in people through a healing process in which Pitter Přemysl restored his sense of hope. The painting depicts the bent figure of the young Bacon being led by Přemysl through a ray of light, lifting him from the darkness and death of the camps towards light and life.

"Pitter was a wonderful person, and it was he, in my opinion, who saved us from the horror of the past. That was the first time that we gave our trust to another human. […] His good-heartedness and that of his friends changed us."

(Yehuda Bacon)

Another example is that of Primo Levi when he refers to Lorenzo Perrone,

"…I believe that it was really due to Lorenzo that I am alive today; and not so much for his material aid, as for his having constantly reminded me by his presence, by his natural and plain manner of being good, that there still existed a just world outside our own, something and someone still pure and whole, not corrupt, not savage, extraneous to hatred and terror; something difficult to define, a remote possibility of good, but for which it was worth surviving.

…But Lorenzo was a man; his humanity was pure and uncontaminated, he was outside this world of negation. Thanks to Lorenzo, I managed not to forget that I myself was a man.”3

- Primo Levi, If This is a Man (New York: The Orion Press, 1959).

We recommend starting the discussion about the return to life after liberation by pointing out that rehabilitation wasn't at all obvious.

Survivors confronted critical decisions but were at a very low point of personal emotional resources, and were often in great physical distress. They needed to find answers that would enable them to continue to go on living when all was lost, but they also needed to search in order to see whether anything remained of their lives.

- Where should they go?

- Were there any survivors from their family?

- How can one go on living after the Holocaust?

- What does the word "life" encompass?

- What values can be trusted when your entire world has collapsed?

Rebuilding a life is not an obvious act; similarly, it is nothing short of miraculous that after the Holocaust Millie as the majority of survivors did not lose faith in life, mankind and society. After the trauma and loss she had experienced, she could have easily turned into an embittered person, filled with hate and build on seeking revenge, but the opposite took place.

"In those days, everyone was looking to start over. The young men wanted to settle down, take care of someone, and have someone take care of them. They wanted other things, too, of course, but it was marriage most of all that they were looking for."

- Why do you think the young men were so eager to form relationships and to marry?

- What can this tell us about the human spirit?

The educational emphasis should be on the fact that the path chosen by Millie was constructive rather than destructive. Millie channeled her energies into blazing paths of continuity, by marrying and raising a family, and by finding purpose in her future.