Introduction

In 1970 Dan Pagis published a collection of his poems under the name ’Gilgul’. These were the first poems he wrote that were directly connected to the Holocaust. A period of twenty-five years had to pass before he was able to approach the experiences he suffered as a child in the Holocaust and frame them in verse. One of the poems that has been widely anthologized is also perhaps one of the shortest poems written on the subject of the Holocaust and yet, the themes emanating from this poem are many and varied.

In the body of the poem there are nineteen words that appear in six short lines and except for one word – transport – there is no mention of the Holocaust. This word together with the word ‘freightcar’ in the title are little evidence to indicate a literary creation brimming over with anxiety, allusions to the tragedy and powerful statements, all unstated, about human history. The metaphor that Pagis has used to present ideas on the Holocaust is the first murder on earth, Abel slain by his brother Cain. The biblical story from chapter four of Genesis becomes Pagis’s vehicle for suggesting connections to the twentieth century tragedy, which in this poem is held at one remove.

The accompanying slideshow presentation (PDF) suggests various themes that emerge from the poem and its biblical inspiration and each point is elucidated in a paragraph below. The reach of themes addressed is wide and it is certainly possible for teachers to choose specific points of interest for their class.

The following is a list of themes that emerge and beg amplification.

- The use of the first biblical family as a prototype for human relations to come

- The place of mothers in the biblical story and in the Holocaust

- The human need to leave testimony

- Holocaust denial

- The meaning of the ‘Mark of Cain’

- The brotherhood of man

- The Days of Awe and the theological question

Educational Objectives

The purpose of this Teacher’s Guide is to open up new avenues of approaching one of Pagis’s most well known poems. The themes suggested in the accompanying slideshow presentation (PDF) are based on an intimate linking of the four verses in Genesis that deal with Cain and Abel, and the poem itself. The teacher can choose to deal with as many or as few themes as suit the pupils and the teacher’s own objectives.

The poem is so short and condensed and its conceptual reach is so wide and varied that the teacher would do well to define his/her aims in choosing which themes to address.

We limit our directives here to Paul Celan’s statement quoted twice in this guide and once again here at the outset:

“Reality for a poem is in no way something that stands established, already given, but something standing in question...”

The reality of this poem will be created and defined by the discussion and path traveled by each class that deals with it. Perhaps that’s what the poet intended...

Presentation of the Poem, the Four Verses from Genesis and the Themes Emanating from Them

View or download a PDF of the slideshow presentation of the poem and its themes.

Notes to the Teacher on each Theme

The Use of the First Biblical Family as a Prototype for Human Relations to Come

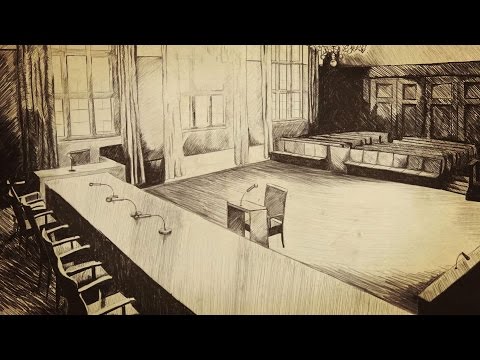

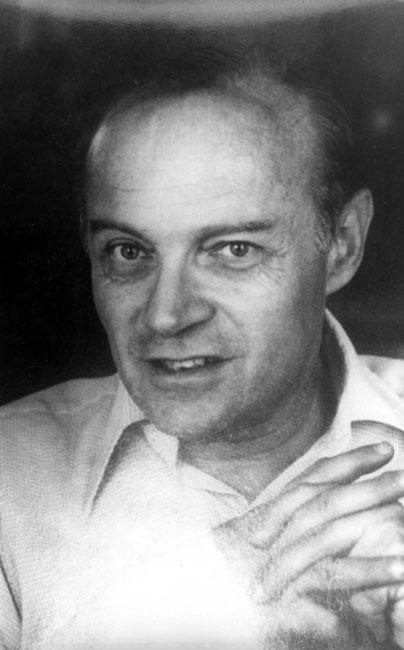

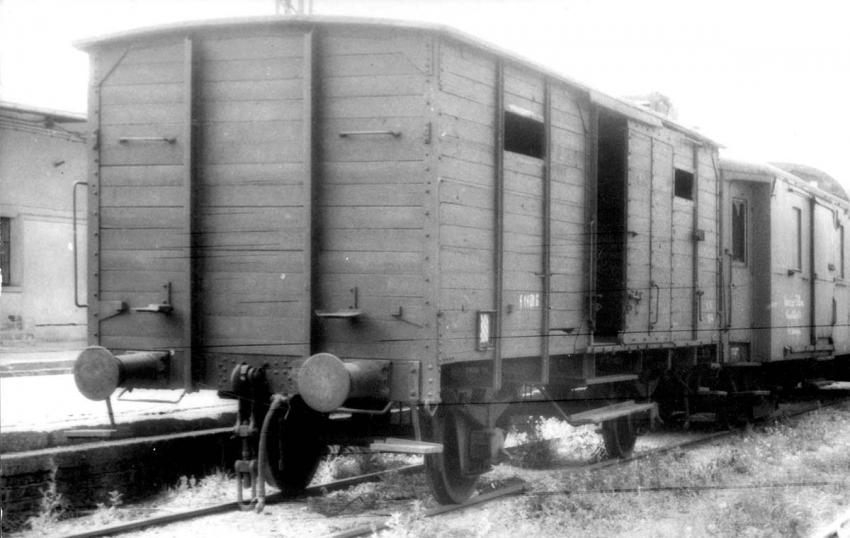

Dan Pagis was a child of nine when war broke out and barely two years older when he was thrust onto a German transport with his grandparents from their home in Romania en route to a German labor camp. Thirty years later, the poet/survivor Pagis opts to portray the horrors of his situation by placing Eve and Abel into the freightcar and not himself and his grandparents. His own biological mother died when he was a child of four, some five years before the outbreak of the war and shortly before this tragedy his father had left to set up a home in Palestine for the family. We know from his wife Ada Pagis who wrote a biography about her late husband that for all their married years together, she was unable to get him to talk, even to her, about his experiences either in the train en route or in the subsequent reality of camp life. Thus, after the hiatus of 25 years, Cain and Abel and Adam and Eve will represent for Pagis the family fabric that he never enjoyed as a child and these four figures will take on the various ominous meanings dealt with below.

Jealousy and Murder as a Constant Factor within Man

If jealousy was a main factor in Cain’s murder of Abel, the multiple murder of the twentieth century stands on its own without pinpointing the exact contribution of this human emotion in the case of the Nazis. One of the central extrapolations to be made from the poem is the uninterrupted history of murder that marks man’s history from its early beginnings to the modern age. Pagis’s choice of the first universal family from the Book of Genesis to portray the evil instinct of man and to link it to the mass murder of ensuing centuries down to the Holocaust turns his poem into a distilled and poignant statement about the nature of man. It is a pessimistic message with no frills and no reprieve. Even the unfinished message would seem to evoke the somber colors of impending doom. The German train network transported four million Jews in Europe to their deaths, among them Pagis’s grandparents.

The last line of the poem is left unfinished, enabling the poem to be read cyclically, ad infinitum. The effect created is of the German trains running non-stop to accomplish their task of murdering Jews. This idea can be applied metaphorically to indicate the smooth continuum of repeated murder in the history of man, as mentioned above.

In the conclusion to this Teacher’s Guide, we will discuss the possibility of alternative readings.

The Place of Mothers in the two Tragedies

Pagis has placed the mother of the victim and the murderer at the center of the poem. In the biblical story, Eve is not at the heart of the events. Pagis has chosen to present all the pathos of the first murder through the eyes and experience of the bereaved mother and thereby to highlight the place of women in the Holocaust. This emphasis of the poet on feminine suffering in the biblical and Holocaust setting precedes historical research on the role of women in the Holocaust by more than a decade. The academic investigation of the role of women in this tragedy started in the second half of the eighties and Pagis published this poem in 1970.

Pagis, it appears, felt deeply in his poetic soul the need to address the plight of mothers and women in the Holocaust, long before academe picked up the cudgels. His own mother had died in 1934 when he was only four years old and he was brought up by his grandparents until the outbreak of war. From this lack in his own life, he places the biblical mother Eve at the center of the poem. However, when it comes to the crux of her message the reader is left imagining what she was planning to write. The word picture Pagis has given us is a tribute to the role of the mother in the total absence of a father. She is providing the human warmth to her younger son Abel as they speed to their fate in a German freightcar. The unwritten message at the end of the poem is an eloquent silence testifying to the unspeakability of Eve’s situation. But it also highlights her bravery in attempting to make contact or leave some form of testimony

Teachers who address this theme with their pupils might use another poem Pagis wrote specifically about his mother, which he entitled in German, Ein Leben.

The Human Need to Leave Testimony

An outstanding feature of this short poem is its non-completion. The last line, “Tell him that I” leaves the message that Eve wishes to convey to Cain unspoken. With Pagis’s knowledge of the Bible, it becomes clear that part of the inspiration to leave the message unsaid comes directly from Genesis chapter four, verse eight:

“Cain said to his brother Abel…and when they were in the field, Cain set upon his brother Abel and killed him.”

Note: The Hebrew Bible appears as above, completely omitting the words spoken by Cain to Abel. Some English translations have inserted his unspoken words.

So it appears as if Pagis is mimicking Cain’s inability to express his negative emotions to his brother, just as he leaves Eve speechless, facing the magnitude of her approaching fate in a German cattle-car.

Pagis has subtly contracted time frames by using the present tense in a poem, which invokes two historical time frames, the biblical and the time of the Holocaust. He thus catapults the reader from his/her usual armchair comfort into the maelstrom of the action. We, the readers, are requested to pass on the unformulated message, clearly implying that we also have to bring it into being, to write it. It is a masterstroke of actively involving the generations after the Holocaust in the messages of the Holocaust by first and foremost having to formulate them. This exhortation from a survivor/poet reflects fears of survivors that Holocaust memory will dim with the passage of time, and this poem of Pagis is a means of safeguarding this memory so that perhaps chances of its repetition in history will be diminished. On the practical plane, Pagis has presented teachers with a vehicle to elicit pupils’ reactions to the context of the train transports within the final solution, with the pupils suggesting the content of Eve’s unspoken message. The ensuing discussion in the class contributes to a pupil appreciation of the complexities.

Thus, through this poem, we, the subsequent generations, are constantly reformulating the message that the Eve of the poem or the mother in the Holocaust were unable to express, but according to Pagis, were intent on leaving us.

Holocaust Denial

In Genesis, chapter four, verse nine, the reader of the Bible is struck by Cain’s unabashed denial of Abel’s murder. The words, so simple and so eloquent, and strangely so because of their negative content, have reverberated in man’s lexicon since their initial utterance:

‘I don’t know. Am I my brother’s keeper?’

When Pagis wrote the fifth line of his poem, ‘Cain, son of Adam,’ he was submitting to his readers everything negative that is associated with this name: the first murder, the brash denial thereof and the famous or infamous ‘Mark of Cain’. None of these are explicit in the poem. All of them are a clear and integral part of the biblical story and as such part of the recognized canon. Pagis is undoubtedly invoking them and in the case of the ‘denial’, a direct parallel is being drawn to the modern version of Holocaust Denial in this and the preceding century.

It is known to what an extent the resurgence of neo-Nazism and accompanying Holocaust Denial was an intense irritant to survivors after the war and this poem contains its own reference to the phenomenon.

The Meaning of the ‘Mark of Cain’

The Cain of Pagis’s attention is the big brother who is to be apprised of his mother’s message as soon as contact is made with him. But in such a short poem, the reader is behoven to fill in the gaps and interpret the pregnant meanings brimming in every word, phrase, person and picture in the six lines of the poem. And so it is with the name Cain, a synonym for the ultimate perpetrator and embodiment of the idea of evil in human relations.

From Genesis 15:4, the mark of Cain has become one of the most accessible and remarkable concepts in any society where the Bible is read. The prevalent idea of the ‘mark’ is to serve as a signpost that demarcates the permissible from the impermissible. The system of judiciaries, courts and prison frameworks is all part of the modern application of the mark of Cain.

However, verse fifteen also includes the idea of protecting the murderer from those seeking to wreak revenge on him. Various options exist for interpreting this idea in the Bible.

We will limit our treatment of this verse by suggesting that what Pagis is presenting in the poem through the brothers Cain and Abel is a blurring of the distinction between the victim and the perpetrator. However, the Bible student often understands this verse to indicate that Cain the murderer is promised protection. Pagis survived the Holocaust in which six million Jews were not afforded similar protection. His reactions to this trauma are difficult to gauge from this poem in which displacement of pain receives ultimate expression. However, other poems like Roll-Call or Testimony indicate very clearly this blurring of the line between victim and perpetrator and the “I” of the victim is much more tangible. For the perpetrator, the ‘mark of Cain’ is transformed in these two poems into a mark of distinction and the victims are reduced to smoke. The poet’s tone is finely honed irony. In this poem, the idea of the ‘mark of Cain’ remains for Pagis undefined and problematic.

This concept – so central for so many, insofar as it demands our attention in this poem because of Cain’s looming presence – should be filtered through the lens of a Paul Celan statement made in 1958 about poetry:

“Reality for a poem is in no way something that stands established, already given, but something standing in question...”

The Brotherhood of Man

Another one of the elevated precepts, the brotherhood of man, bears examination through the prism of the poem and the biblical account. The word ‘brother’ doesn’t appear in the poem. The sibling relationship is only alluded to through Eve’s mention of her younger son Abel and in the next line her reference to her older son Cain. Explicit mention of brothers is absent, as is any interaction between them in the poem. The fulcrum of emotion and speech is projected to us through the mother of the brothers.

In the biblical version in verses 8-10, the word ‘brother’ appears five times, implying an idea and its immediate negation. With the seminal story of Cain and Abel, no brotherhood of man is forthcoming from the creation until the Flood and the refashioning of mankind. The fate of this brotherhood of man reaches the apex of its negation again in the Holocaust and subsequent genocides of the twentieth century. Pagis’s poem with its pointed omission presents a pained awareness of this reality.

The Theological Question

Dan Pagis became a professor of Medieval Jewish poetry at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem and lived a secular life-style until he died in 1986. However his knowledge of Jewish sources permitted him to include in the title of this poem a veiled reference to the vexed question of God’s presence or absence during the Holocaust.

Pagis knew that in the prayers of the Days of Awe (from The Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, to The Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur), the prayer Avinu Malkenu [Our Father, Our King] has a special pride of place. For the whole period until the ultimate closing hour of the Day of Atonement this special prayer is intoned several times a day with the words:

“Inscribe us in the book of life,”

“Inscribe us in the book of salvation and redemption,”

with many additional supplications. The operative word for Pagis was ‘inscribe’ or ‘write,’ which he knew is changed in that final hour from inscription to final signature and sealing of fates.

This idea is dramatically present in the title of the poem. The English title begins with the word ‘written’ and the penultimate word is ‘sealed.’ The Hebrew original is even more pointed with the last word of the title being ‘sealed.’ But in Pagis’s powerful system of displacement, it is not man’s supplication that is being sealed but his imminent fate at the hands of the Nazis, in their sealed train system. So Pagis has bridged the traditional Days of Awe during which Jews pray for God’s inscription in the book of life to the days of awe 1939 – 1945 in which god observed the sealed freightcars delivering millions to their death.

The theological question in this poem is not only not stated, it is also veiled in the specially chosen words of the title that conjure up the traditional, praying Jew during the High Holy Days and the fate suffered by so many in the Holocaust.

Conclusion

Conclusions generally bring closure to some linear development or argument. Ironically, I would like to emphasize the cyclical element of the poem mentioned earlier. The six lines of this poem, which contain the seeds of the various ideas discussed above can be read continuously from end to beginning. Is Pagis not conveying to all his readers that by this device, we should all internalize the ultimate repetitive nature of human society – that in the contexts mentioned above, there is no closure?

The answers each reader might suggest to the various questions like: “Why was Cain protected?” or, ”Why is murder an ever present negative in human society with genocides rearing their ugly heads one after the other?” are limitless. The poem is dramatic in its ability to undermine preconceived positions.

The perpetrator is not only ‘the other’ but also your ‘brother.’ I quote from our second point above on the ‘constancy of jealousy and murder’ in order to present an opposite position.

“It is a pessimistic message with no frills and no reprieve. Even the unfinished message would seem to evoke the somber colors of impending doom.”

An opposite reading of the unfinished message is also possible, perhaps as an opening for reconciliation with ‘the other’ who we are reminded was also Abel’s brother.

These contradictory notions are all grounds for fruitful thought, discussion and maybe action. Could this have been one of the ideas in the poet’s thinking? Since each one of us has his/her own answers, perhaps it is fitting to conclude these lesson suggestions with Paul Celan’s statement mentioned before:

“Reality for a poem is in no way something that stands established, already given, but something standing in question...”