This short animated video describes the establishment of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp, the process by which Jews were sent to it, and daily life in the camp until liberation in 1945. Produced by Pil Animation

Abundant information about the Auschwitz Album was publicized during the trial of Adolf Eichmann, which took place in Jerusalem in 1961. Eichmann was a senior SS officer who played a major role in the organization and logistics of the attempted annihilation of European Jewry, known as the “Final Solution.” He was found guilty and sentenced to death.

As the case against Eichmann was being prepared, articles were published in the press in the United States and Europe which mentioned the album, and Lili Jacob was interviewed several times.

The album also received coverage in the press during the trials of German criminals who served in Auschwitz, that took place in Frankfurt, Germany between 1963 and 1965. Dr. Erich Kulka was the first witness to mention the album in court and describe how Lili found it. During the course of the trial, the identities of the two SS photographers who took the pictures—Bernhard Walter and Ernst Hoffmann— were revealed. They were the official Auschwitz camp photographers and were among the few in the camp who were permitted to take pictures there. Even though he appeared in several sessions of the trial over the course of a year and a half, Bernhard Walter succeeded in deceiving the court, leaving the question of the identity of the photographers uncertain. His deputy, Ernst Hoffmann, had already disappeared after the war, so it was impossible to interrogate anyone else about this album.

Based on Dr. Kulka’s recommendation, the Frankfurt court invited Lili Jacob-Zelmanovic, then living in the United States, to testify. On December 3, 1964, Lili appeared on the witness stand holding the original album. The album was submitted as evidence, and she described its discovery and referred to certain SS-men seen in the pictures. The court requested that she leave the album as evidence, but she refused, and it remained in her possession until it was presented to Yad Vashem.

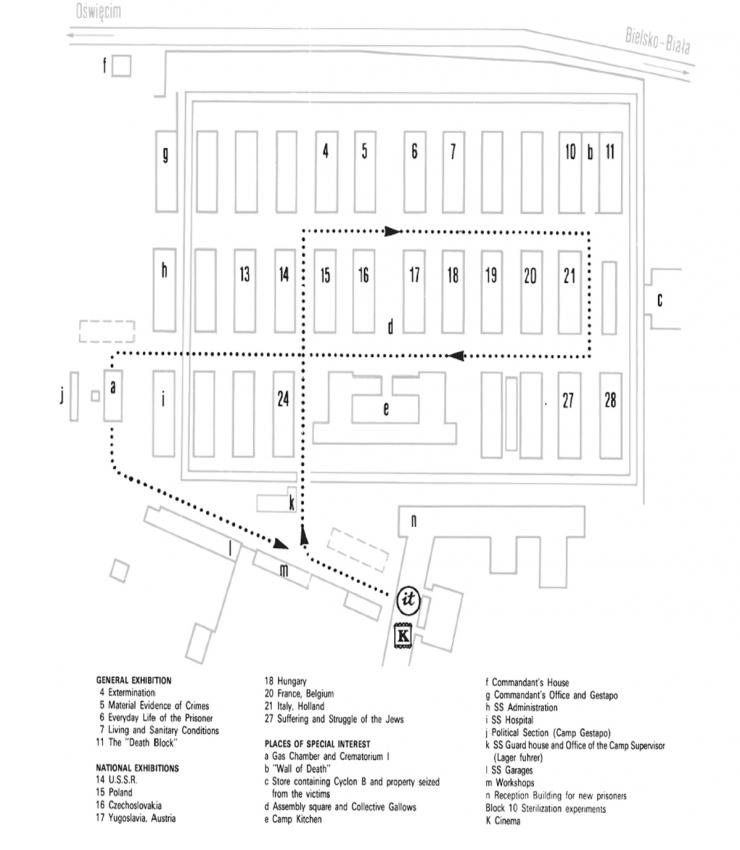

The Auschwitz-Birkenau complex was the largest Nazi extermination and concentration camp, 37 miles west of Kraków. One sixth of all the Jews murdered by the Nazis were gassed at Auschwitz.

In April 1940, SS Chief Heinrich Himmler ordered the establishment of a new concentration camp near Oswiecim, a town located within the portion of Poland that was annexed to Germany at the beginning of World War II. The first Polish political prisoners arrived in Auschwitz in June 1940, and by March 1941 there were 10,900 prisoners, the majority of whom were Polish. Auschwitz soon became known as the most brutal of the Nazi concentration camps.

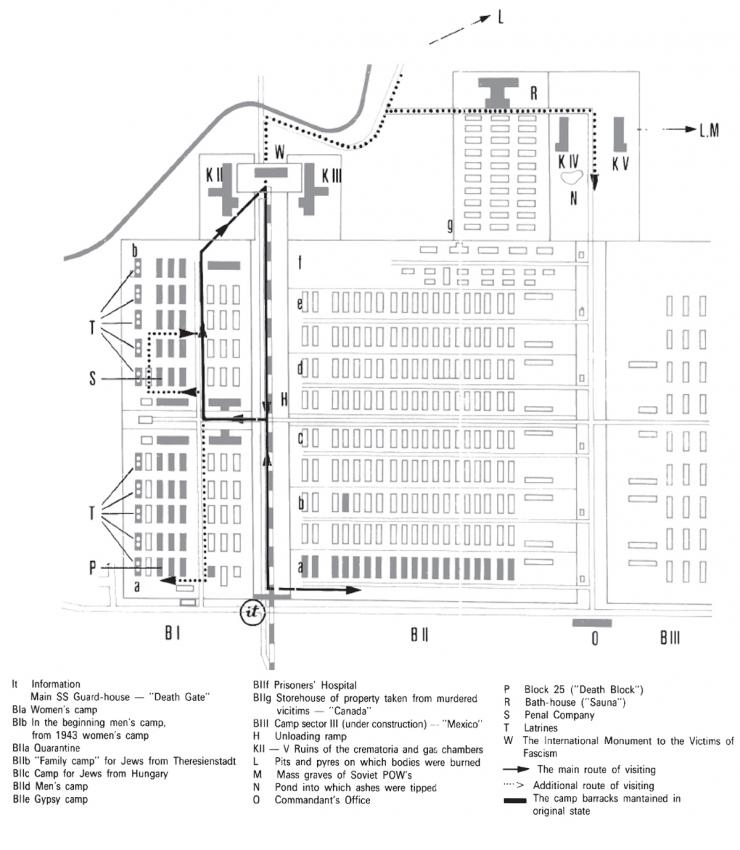

In March 1941, Himmler ordered a second, much larger section of the camp to be built 1.9 miles from the original camp. This site was to be used first as a huge prisoner of war camp and later on as an extermination camp and was named Birkenau, or Auschwitz II. Eventually, Birkenau held the majority of prisoners in the Auschwitz complex, including Jews, Poles, Germans, and Gypsies. Furthermore, it maintained the most degrading and inhumane conditions—and included the complex’s gas chambers and crematoria.

A third section, Auschwitz III, was constructed in nearby Monowitz, and consisted of a forced labor camp called Buna-Monowitz. The name Buna was derived from the Buna synthetic rubber factory on site, owned by IG Farben, Germany’s largest chemical company. Most workers at this and other German-owned factories were Jewish inmates. The intense labor would push inmates to the point of total exhaustion, at which time new laborers replaced them. The whole Auschwitz complex incorporated 45 forced labor sub-camps.

Auschwitz was first administered by camp commandant Rudolf Hoess, and was guarded by a cruel regiment of the SS “Death’s Head” Units. The staff was assisted by several privileged prisoners who were given better food and conditions, and an opportunity to survive, if they agreed to enforce the brutal order of the camp.

Auschwitz I and II were surrounded by electrically-charged four-meter high barbed wire fences, guarded by SS men armed with machine guns and rifles. The two camps were further closed in by a series of guard posts located two thirds of a mile beyond the fences.

In March 1942, trains carrying Jews commenced arriving daily. In many instances, several trains would arrive on the same day, each carrying one thousand or more victims coming from the ghettos of Eastern Europe, as well as from western and southern European countries. Throughout 1942, transports arrived from Poland, Slovakia, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Yugoslavia, and Theresienstadt. Jews, as well as Gypsies, continued to arrive throughout 1943. In March 1943, nineteen transports from Thessaloniki, Greece arrived to the camp. Hungarian Jews were brought to Auschwitz in 1944, alongside Jews from the remaining Polish ghettos.

By August 1944, there were 105,168 prisoners in Auschwitz and Birkenau, while

another 50,000 Jewish prisoners lived in the various satellite camps. The camp’s population grew constantly, despite the high mortality rate caused by extermination, starvation, hard labor and contagious diseases.

Upon arrival at the platform in Birkenau, Jews were thrown out of their train cars without their belongings and forced to form two lines, separating men and women. SS officers, including the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele, would conduct selections along these lines, sending most victims to one side and thus condemning them to death in the gas chambers. A few were sent to the other side, destined for forced labor. Those who were sent to their deaths were killed that same day and their corpses were burnt in the crematoria. Those not sent to the gas chambers were taken to the “sauna,” where their hair was shaved, striped prison uniforms distributed, and they were registered. The registration numbers were tattooed onto their left arm. Most prisoners were then sent to perform forced labor in Auschwitz I, III, sub-camps, or other concentration camps, where their life expectancy was usually only a few months. Prisoners who stayed in quarantine had a life expectancy of a few weeks.

The prisoners’ camp routine consisted of many duties. The daily schedule included waking at dawn, straightening one’s sleeping area, the morning roll call, the trip to work, long hours of hard labor, standing in line for a pitiful meal, the return to camp, block inspection, and evening roll call. During roll call, prisoners were made to stand completely motionless and quiet, sometimes for hours, in extremely thin clothing, irrespective of the weather. Whoever fell or even stumbled was killed. Prisoners had to focus all their energy merely on surviving the day’s tortures.

The gas chambers in the Auschwitz complex constituted the largest and most efficient extermination method employed by the Nazis. Four chambers were in use at Birkenau, each with the potential to kill up to 6,000 people daily. They were built to look like shower rooms in order to confuse the victims. New arrivals at Birkenau were told that they were being sent to work, but first needed to shower and be disinfected. They would be led into the shower-like chambers, where they were quickly gassed to death with the highly poisonous Zyklon B gas.

Some prisoners at Auschwitz, including twins and dwarfs, were used as the subjects of torturous (and completely unethical) medical experiments. They were tested for endurance under terrible conditions such as extreme heat and cold, or were sterilized.

Despite the horrifying conditions, prisoners in Auschwitz managed to resist the Nazis, including some instances of escape and armed resistance. In October 1944, members of the Jewish Sonderkommando, who worked in the crematoria, succeeded in killing several SS men and destroying one gas chamber and crematoria. All of the rebels died, leaving behind diaries that provided authentic documentation of the atrocities committed by the Germans at Auschwitz.

By January 1945, Soviet troops were advancing towards Auschwitz. In desperation to withdraw, the Nazis sent most of the 58,000 remaining prisoners on death marches to Germany, and most prisoners were killed en route. The Soviet army liberated

Auschwitz on January 27; soldiers found only 7,650 prisoners barely alive within the entire camp complex. In all, at least 1.1 million Jews had been murdered there.

The camera is a mighty tool. When it freezes a fraction of a visual second, that moment is preserved forever. Thus, historians consider the camera an important, powerful tool.

World War II and the Holocaust period left us many photographed moments and scenes. Some of them, such as the picture of the boy from the Warsaw ghetto, are so familiar and well known that it seems as though we could not do without them; we think of them as hallmarks of a dark era in the history of the European continent.

The National-Socialist regime of Germany recognized the power of the camera and both the positive and negative opportunities that it presented. Throughout their rule, the Nazi leaders took full advantage of this instrument. They distributed hundreds of thousands of antisemitic photographs in an effort to mold German public opinion and spread ideological antisemitism in the German people from the very beginning of the anti-Jewish actions. Throughout the enactment of the Nuremberg Laws, the Aryanization of Jewish property, the establishment of the ghettos, the deportation to concentration camps, and even the implementation of the Final Solution itself, the camera was the Nazis’ faithful assistant.

The camera also served the liberators. The Allied soldiers used it a great deal to document what they saw when they liberated the death camps. After the war, photographs were used extensively as eyewitness testimony and as incriminating documents against Nazi criminals when many of the leaders of the regime were prosecuted in the Nuremberg trials, the Eichmann trial, and other trials over the years.

A photograph creates a sense of direct access to reality. Even if this reality has already passed, the photograph captures a cross-section of time from the past and documents it in print. Time etched in print leaves an indelible impression on the individual’s memory and remains a public legacy for the future. While observing the visual fragment of time, one can go back and concentrate on the details, which then may evoke thoughts and memories. Photographs are powerful, and they retain a respected place even in the age of the motion picture.

Nevertheless, despite the inherent power of photographs, they are also vulnerable. After all, while they may be regarded as the product of mere technical activity, they are not necessarily objective. Like all historical documents, photographs have a personal perspective. The photographer chooses the time and angle and has the technical means to manipulate by means of light and shadow, blurring or emphasis, reduction or enlargement. Even after the photographer’s job is finished, other factors come into play that can influence and change things. The thematic setting of the photograph, the context in which it is printed, the wording of the caption can

all produce different interpretations and alter the historical truth. Historians must, therefore, examine the details of the photograph as critically as if they were studying a historical document. Paramount importance must be ascribed to identifying the people in the photograph, the photographer, the date of the photograph, names, and as many details as possible.

The Use of the Camera during the Nazi Period

The years preceding the Nazis’ rise to power constituted a peak in the development of photojournalism. Photographs achieved special recognition due to the manufacture of the commercial camera and its widespread use by the general public. The availability of the portable, compact Leica camera, which replaced the static studio cameras, opened up new photographic options, as it became possible to take spontaneous outdoor photographs from many different angles.

The Nazi authorities, who took advantage of the camera as a means of glorifying the Reich and its leaders, persuading people, molding public opinion, and disseminating their racial doctrine, were aware that cameras could offer evidence against them. Therefore, laws were enacted forbidding photography inside the ghettos, camps, and other sensitive areas. Professional Nazi photographers worked under government supervision. The photographers in the propaganda units that operated at the front, press photographers, and independent photographers working for the foreign press in Germany were all subject to strict censorship.

There were, however, other people who could take pictures freely and were more difficult to supervise. These were German civilians who owned cameras and German soldiers who carried their private cameras with them and documented the period in personal albums. Hundreds of photographs, some of them in color, document the lives of the Jews in large ghettos such as Warsaw and in small ghettos as well. Photo series and personal albums of German soldiers and policemen immortalize “Jewish types,” against the backdrop of poverty, hunger, and crowded ghetto conditions, and document the abuse of Jews, Aktionen, and deportations. In some cases, German soldiers even took pictures of the murders carried out by the soldiers of the Einsatzgruppen. Concern that this evidence might circulate prompted army commanders to forbid photography and to issue orders to confiscate photographs of the activities of the Einsatzgruppen.

Jewish photographers in Germany also documented the period with their cameras. The most prominent ones, who worked for the German press during the period of the Weimar Republic, were dismissed in the wake of the Nuremberg Laws. A few were hired by the Jewish press, which remained active until the deportations; with the aid of their cameras, they left important documentation on the life of the Jewish community in Germany. Photographers such a Mendel Grossman in the Lodz ghetto and Zvi Hirsch Kadushin (Goerge Kadish) in the Kovno ghetto used their cameras to document ghetto life. Collections of their photographs are now in archives, serving as testimony and historical documentation for future generations.