Introduction

IntroductionThe Holocaust – an unprecedented tragedy that afflicted an entire nation – dealt a death blow to the social fabric of European Jewry, foremost of which was the structure of the Jewish family. Long before the onset of the mass murders in Germany and in German-occupied territories, particularly in the east, a process began that impacted the Jewish family unit. Already at the early stages of the occupation, many Jews were forced to contend with the loss of or separation from close family members, who either fled to other locations or were deported to an unknown fate. Incarceration of Jews in conditions of overcrowding and deprivation in the ghetto, the lack of privacy, and high death rates also heavily impacted the family unit. Even so, family togetherness was a significant anchor in the days of terror, and in areas where families were torn apart from one another and scattered to different places, this constituted a great crisis.

We have chosen to discuss the Jewish family in the Holocaust by means of various artifacts that reflect, on one hand, the crisis itself, and on the other, the intimacy and closeness within families and their attempts to cope with the difficulties they faced.

It is important to remember that most of the artifacts belonging to Jews were taken from them, destroyed or disappeared, leaving us unable to complete the picture of the lives of the victims. Especially in light of this, the few artifacts that did remain are of great value. In those grim times, many objects changed their function, a process that was often painful and difficult. Thus studying the narratives behind the artifacts enables us to touch the human story.

In this lesson, we will deal with questions raised from discussing the artifacts and the stories behind each of them, such as: What was the original function of the artifact? Did this function change, and if so, how? What was the significance of giving or receiving this artifact? What was the meaning of holding on to it? In what ways does the artifact's story reflect that of the family? How does the artifact shed light on the story of the Jewish family during the Holocaust?

Lesson structure

- Introduction: Discussion of the poem "Things" – Wladyslaw Szlengel

- Personal or group work regarding the artifacts

- Summary

Opening Discussion - Poem

Opening Discussion - PoemIn his poem “Things,” the Jewish poet Wladyslaw Szlengel, who was murdered in the Warsaw ghetto, describes the process of rupture and loss that the Jews experienced during the Holocaust. The poet chose to describe this process by focusing on the ever-decreasing amount of belongings Jews were able to own. Beginning with the description of the carts brought by Jews into the ghetto, the poem ends with their final journey in the trains to the camps, with only a single bag.

From Marszalkowksa, Hoza, Wspolna Streets, sagging….

Jews, their wagons were dragging….

Cupboards, tables and chairs,

Trunks and boxes, home wares.

Bulging suitcases, bedding,

Jugs and photos of weddings.

Suites of furniture, portraits,

Drapes, wall-hangings and carpets.

Glassware, jugs, cherry brandy,

All that may come in handy.

Books and pots, the whole treasure.

Roll to Sliska from Hoza,

Into coat pockets cramming

Vodka, hunks of salami.

Wagons, carts, the sad throng

Drags its sad feet along.

Thus they moved on from Sliska

Street over to Niska:

Cupboards, tables and chairs,

Trunks and boxes, home wares.

Pots and frypans and bedding.

But no photos of weddings,

No knick-knacks, no carpets,

Silver's gone and the portraits,

There are no jugs or bottles,

No suites, no books, no kettles,

Left behind now the sack

Full of prized bric-a-brac.

In coat pockets still cramming

Vodka, hunk of salami,

In one cart all possessions,

Walks the gloomy procession

Niska now left behind

In the "block" all confined

With no cupboards, no chairs,

With no boxes, home wares,

With no glassware, no jugs,

With no frypans, no rugs,

Disappeared, gone to blazes

All the silver and vases

In one hand a valise,

A warm scarf… only these,

Some cold tea in a flask

And for bread, a small rusk,

Hauling things step by step,

Through the night trudged and wept.

To Ostrowska from the block

Down their Jewish road they walked.

Without tables or chairs,

Without boxes, homewares,

With no beds and no bedding,

Tea things all gone already,

Dragging still one valise,

One warm scarf… besides these

Bottle filled from a tap,

Backpack hung by a strap.

Treading over things – thus

Down the dark streets they passed.

[…]

Umschlagplatz, through the city,

By the main thoroughfares,

Empty houses emitting

Jewish life which still stirs

In the rooms just abandoned

The left-behind bundles,

Suites of furniture, blankets,

China dinner sets, candles,

Fires flickering in chimneys,

Spoons abandoned on platters…

Lie betrayed in the hurry

The old family photos….

Book on table, half-open,

Letter scrap: "You're hard-hearted…"

Cup of coffee, unfinished.

Card game, only just started.

A cool breeze through the window

Moves a nightgown of lace,

And a blanket lies crumpled

As if in last embrace,

Things exist there, unclaimed,

The dead house stands in silence,

Till it's suddenly filled

With some…

New Aryan tenants…

[…]

On the night of the terror,

The bullet and blade,

From trunks and from houses

Jewish things will escape,

Escape through the window,

Proceed down the street,

The black rails at the highway

Is where they'll all meet:

All the tables and chairs,

Bundles, boxes, home wares,

Suites of furniture, jugs,

Stools and kettles and rugs,

They shall leave, disappear,

None will guess what this means

That things walk off like that

Nevermore to be seen.

After reading this poem, discuss the following questions:

- What is the process that Szlengel describes? Why does he choose to describe this through artifacts?

- What is the significance of the artifacts?

- Why is he disturbed by their loss?

Szlengel describes a process endured by the Jews, starting from the transition to the ghetto and then within the ghetto, from place to place. The reduced number of possessions signifies the material, emotional and spiritual degradation experienced by the Jews, as well as their physical disappearance. The possessions we collect in our lives are a combination of functional items, such as a bed, dishes, etc., which sometimes carry within them some sentimental value, along with items that express a spiritual or emotional world, such as ritual artifacts, books and jewelry.

As stated, most of the possessions belonging to Jews, expressions of a vibrant and diverse world, were stolen, destroyed or disappeared, leaving us unable to complete the picture of the lives of the victims. And especially in light of this emptiness, the few artifacts that remain are particularly important.

- Wladyslaw Szlengel, What I Read to the Dead (Israel, 1987), pp. 111-112.

- Naomi Morgenstern, The Daughter We Had Always Wanted (Jerusalem, 2003), pp. 32-38.

- Recreated from Yad Vashem’s website: http://www1.yadvashem.org/education/lessonplan/hebrew/Family.htm

- From an oral testimony given in the artifacts wing of the Yad Vashem Museum.

- Ka-Tzetnik, The Clock (Israel, 2000), p. 87.

Opening Discussion - Testimony

Opening Discussion - TestimonyView the testimony of Eliezer Eilon

- Why did Eliezer not wish to separate from his mother?

- Why did Eliezer's mother give him the mug?

- Why, in your opinion, did Eliezer keep the mug throughout the years?

From an educational perspective, an important aspect of studying the story of Jewish families through the objects they held onto throughout the Holocaust is that they create empathy, since students are familiar with such objects from their own world. Due to the tragic circumstances of the family members, these artifacts gain additional significance.

In addition, a single artifact allows the retrieval, from amongst the unfathomable larger Holocaust story, of an individual story, which helps make the larger history more comprehensible.

In the Holocaust, the artifact, even if it was originally a private belonging, expresses the longing to be together once more, the memory of family closeness that maintains a connection between the lone individual and the family.

The fact that the artifact that remained from the Holocaust can be seen and touched, makes us feel as if we are somehow touching the past. Sometimes a single artifact makes it possible to extract from within it the larger story of the Holocaust.

From Yad Vashem's Artifacts Collection, we've chosen several items that reflect different aspects of the family story during the Holocaust, and classified them into various categories.

Divide the class into groups and give each the stories of various artifacts from one category, along with the accompanying questions.

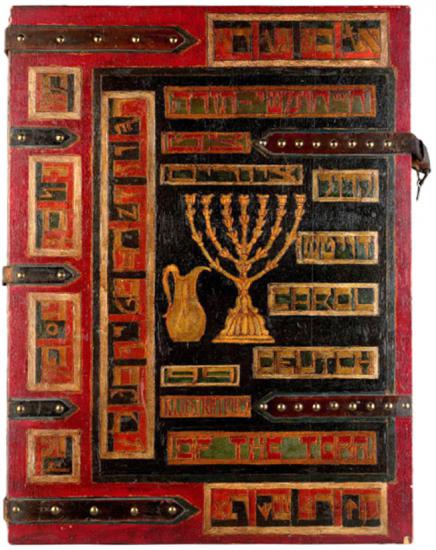

Education and Heritage: Bible

Education and Heritage: Bible[Download Handout for students]

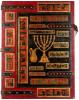

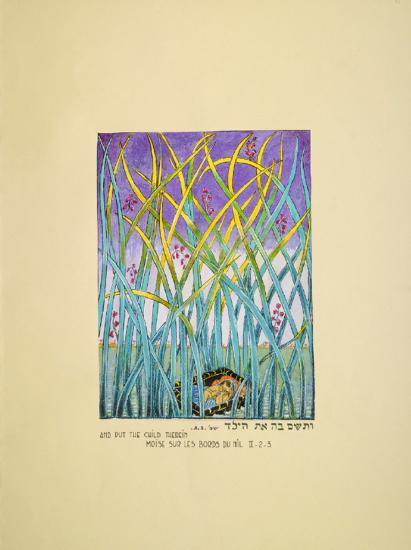

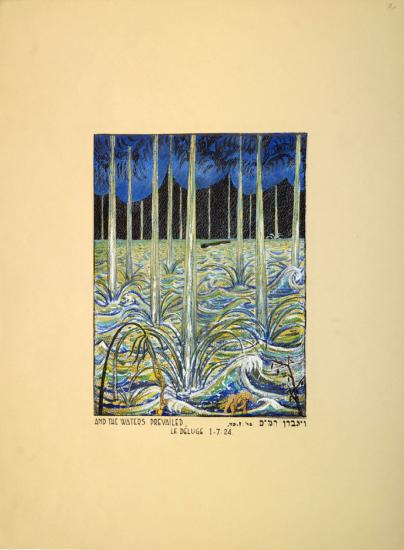

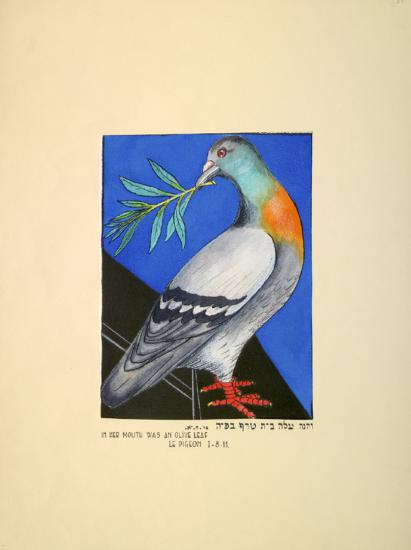

At the end of the war, Ingrid and her grandmother Regina returned home after hiding with a Catholic family in Antwerp, Belgium for 18 months under false identities. They learned that the Gestapo had emptied their home of furniture and valuables, but to their surprise a large wooden box, a masterpiece adorned with a Star of David and a menorah, remained in the house. Inside were 99 drawings, drawn over the course of a year from 1941-1942 by Carol Deutsch, Ingrid's father. For Ingrid's second birthday, already living under German occupation and under the threat of anti-Jewish measurements, Deutsch used his brush to make paintings for her.

The drawings, in spectacular gouache and watercolors colors, depict biblical scenes and characters. The artwork is influenced by subjects, symbols and motifs from Jewish sources, and show his expertise in and connection to his Jewish heritage. The choice to leave his daughter the biblical drawings is a form of resistance against all the Nazis sought to destroy, and is also an expression of love for Ingrid and his wish to connect her to her Jewish heritage.

Deutsch was living in hiding with his wife Fela and under an assumed identity when they were caught and sent to Auschwitz, where Fela was murdered. Carol was sent first to Sachsenhausen and from there on a death march to Buchenwald where he died.

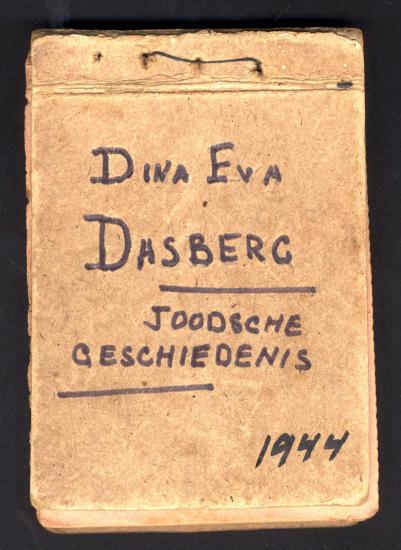

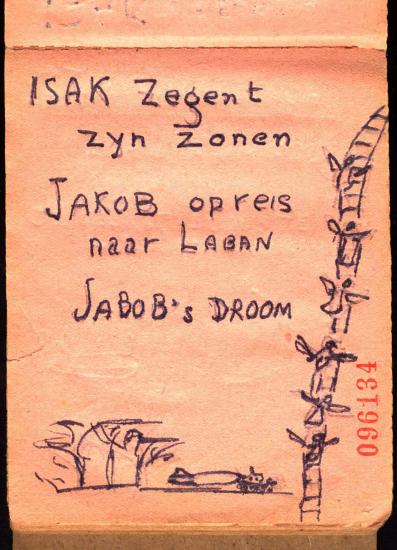

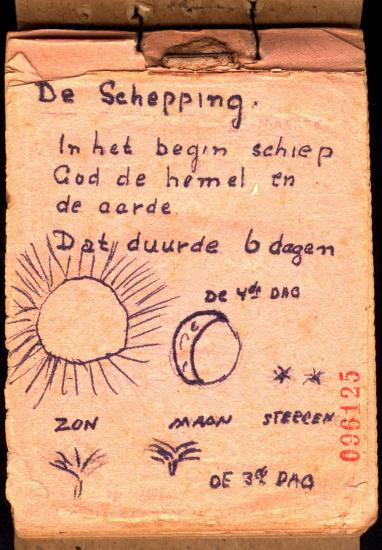

Education and Heritage: Dina Dasberg

Education and Heritage: Dina Dasberg[Download Handout for students]

Dina Dasberg was seven-and-a-half years old when she arrived at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp with her family from Holland. Men and women were separated, and Dina was imprisoned along with her mother and grandmother.

The long days in the camp were difficult. There was a lack of food and Dina, like the other prisoners, was forced to stand long hours for roll call, even in the cold and snow. During her time at the camp she fell ill with typhus, and some of her family died from weakness and disease.

At the age of three, it had been discovered that Dina could not hear. She had no friends in the camp, and spent most of her time with her mother. Dina understood only a little of what was occurring the camp because she could only lipread. On Sabbaths, her mother attempted to give the day a unique character by creating a special meal, albeit with few and meager resources. These special moments were preserved in Dina’s memory as a spot of light within the daily difficulties. Occasionally, her father would manage to visit the section of the camp where Dina and her mother were held. It was not only the desire to see her father than lent these meetings their unique quality, but also the fact that he would study with her. Because she could not hear, her father used a receipt book, on which he wrote and drew biblical stories in order to teach her. Dina describes how she eagerly looked forward to these meetings.

When relating to artifacts parents created for their children, it’s worth noting not only the artifact itself and its design but also the content and messages embodied by it, the medium chosen for transmitting the message, and also the significance of being creative as a reflection of hope and faith.

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

Yad Vashem Artifacts Collection

“I had a friend, I had a brother” – Artifacts as friends and family: Colette

“I had a friend, I had a brother” – Artifacts as friends and family: Colette[Download Handout for students]

Playing with dolls embodies a great deal of psychological and sociological meaning. Here are stories of two children for whom the role of doll play was pivotal, and who even exceeded the normal bounds of play.

Claudine Schwartz-Rudel was seven years old when she and her mother fled Paris in the summer of 1942 to join her father, who had escaped earlier. The only thing Claudine took with her was her doll “Colette”, which never left her side. “You are no longer Claudine Schwartz”, her mother told her, explaining that from now on, due to the situation, she would bear the assumed name Francoise Marta. Claudine in turn explained to her doll that she could no longer be called Colette, but rather would also need to be called Francoise. “But in my heart I always called her Colette”, she says.

Claudine’s mother told her to always watch her doll carefully. “I didn’t understand why she that”, recalled Claudine.

When they met her father in southern France, he explained to Claudine that she would again need to change her name, this time to Michelle.

At first, Claudine was hidden in a small room that she was not allowed to leave. From time to time, her mother would come in to make sure she was okay, and to bring her food. When her mother left, Claudine would say to Colette, “You see? Mother cannot stay with me, only you stay with me.”

When she moved with her parents elsewhere, Claudine began to attend the local school. Every day upon returning from the Christian school she raced to her bed to find Colette and share with her the events of the day.

“My doll was with me all the time and I told her everything – she helped me through those dark times”, Claudine says. From holding and embracing the doll so often Colette's clothes disintegrated, and so Claudine’s mother sewed her a new dress with fabric taken from her own nightgown.

In October 1943, Claudine awoke and did not see her doll beside her. Alarmed, she called for her mother. When she entered the kitchen she saw, to her surprise, Colette in pieces and her father fixing it, and didn’t understand why.

Only after the war did Claudine learn that her mother hid several coins wrapped in fabric within the doll as they were about to flee, so that she would have money if needed.

“I had a friend, I had a brother” – Artifacts as friends and family: Bear

“I had a friend, I had a brother” – Artifacts as friends and family: Bear[Download Handout for students]

Fred Lessing was four years old when the Germans invaded Holland. When he was six, the deportations of Jews began.

Fred recalls that his parents knew that at some point they would be deported to a camp, and so a bag was prepared for each member of the family in advance. These bags were left near the front entrance of their home in Delft. One day, a family friend called and told Fred’s parents that they appeared on a list of Jews slated for deportation in the coming hours. Fred was playing upstairs when his mother called Fred and his older brother to come down and from the expression on her face, it was clear to Fred that something terrible was about to happen. She put her arms around her children and said to them “You are Jewish children. But if anyone finds this out they will kill you. We are leaving the house now; do not take anything with you, just wear your coats and we’ll act like we’re going out for a stroll. We don’t want to draw any attention”. Although their bags remained by the front door, on his way out, Fred grabbed his teddy bear “Bear”.

For the next three years, Fred was hidden at a number of houses. Each time his mother would pretend to be someone else: once a woman whose house had been destroyed and was looking for temporary refuge for her son; and once as a woman whose husband had been injured in a traffic accident. The story always changed, and Fred would not remain for long in the same place. At some stage his mother would return and take him to another house. “I understood that I had to be the sweetest, the most polite, the most considerate and always ready to help so that I wouldn’t be thrown out”. Fred did not stay long in any one place. His mother would always show up and take him elsewhere. “I would talk to Bear all the time, share my feelings with him and cry to him”. Bear was the only one who accompanied Fred as he moved from house to house and family to family, learning each time anew how to act in each home. “He was my only connection to my family”.

One day, Fred became ill with a high fever. His mother suddenly appeared and stayed with him for a while. Before she left, she asked him if there was anything he needed or wanted. Fred held up Bear whose head was torn because it had been bitten by a dog during an earlier period of hiding, "I would like Bear to have a new head", he said. When he awoke the next morning, his mother was gone but Bear had a brand new head, created from the lining of his coat.

Fred, his parents and his brother survived the Holocaust. After the war, the teddy bear was kept by Fred until Yad Vashem approached him and asked if he would be willing to loan it for an exhibition on toys and dolls during the Holocaust. Fred requested a number of days to think over the idea of sending his beloved Bear so far away – for him Bear was not just a toy. After careful consideration, he responded to Yad Vashem’s request:

“I spoke with my teddy bear and explained that for the first time ever, we were to be parted. The reason I gave was that he had an important mission – to go to Israel to be part of an exhibition with other toys from the Holocaust, and there he would tell our story to children who would come to visit the exhibition."

Both "Colette" and "Bear" took on several roles at once: normal child’s play that became more significant in a world of isolation, fear and deprivation, as well as a means of helping the adults of the family in their attempts to be saved. The relationship the children developed with the dolls and the roles they played reflected the changes in their lives both in the family dynamic, as well as in the challenges the children faced with various new families. The two survivors had trouble parting from the artifacts and depositing them with Yad Vashem, as they were the only objects that had survived from their childhood – a childhood spent in the shadow of fear.

“Between the Families” – Artifacts as Representations of Identity : Pendant

“Between the Families” – Artifacts as Representations of Identity : Pendant[Download Handout for students]

One of the hardships that children who were hidden in the Holocaust were forced to deal with was the dramatic changes occurring in their lives, most of all as they separated from their parents and began to live in their rescuers’ homes. These were families they did not always know, with an unfamiliar culture, identity and family life, in many cases extremely different from their own.

Marta Goren was born in Czortków, then in eastern Poland. Her mother smuggled her out of the town's ghetto and hid her in the basement of the pharmacy at which she worked. Later, she took refuge in Warsaw under an assumed identity with the Schultz family, whom Marta did not know.

On Sunday, I went with the whole family to pray at church. I was awed by the hushed silence and the opulence of the pictures and statues. I saw that everyone that entered the sanctuary approached the altar, got down on his knees, bowed and crossed himself. And I, Kristina Gryniewicz, decided to prove how devout I was. I got down on my knees as soon as we entered the church and walked on my knees all the way to the altar. When we returned home, Mrs. Czaplińska put ointment on my knees, which I had rubbed raw, and placed a chain with a pendant of the Madonna and her son around my neck.

[...]

After the months in the cellar, I found it difficult to get used to the sunlight. I felt that Mother was very tense and I wanted to make things easier for her, but I was scared. Where was I going? Who were these people? How could they be trusted? Did she know them?

And suddenly, the train stopped and a lot of people got off.

“That’s Lidka”, Mother said pointing to a beautiful girl standing on the platform, and she smiled at me.

I felt calmer. Lidka approached us with a smile, she and mother kissed, she stroked my hair, and immediately removed the ribbon with the cross from around my neck.

“Christians never wear a cross on a ribbon, only on a chain”, she said, handing it to Mother. Mother quickly thrust it into her bag, and Lidka added, “When you come to us, we’ll make sure you have the right kind of chain”.

2

Marta kept the pendant she received from Mrs. Czaplińska, her rescuer, throughout the war and even throughout the long postwar journey from an orphanage to a difficult beginning in Israel. It was a religious symbol that at first was intended to be part of her disguise and the hiding of her Jewish identity, but over time it became a sincere expression of faith; Marta wished to adopt the Christian identity of her rescuers, and in so doing become part of the Schultz family. The pendant carries within it the story of Marta’s wanderings. Firstly, the separation from her mother and her Jewish identity, then her integration into a new family, until the end of the war, when she was traumatically forced to leave her rescuer and head out on a journey of renewed Jewish identity and building a family. It is interesting to think about what motivated Marta to save the pendant for so many years.

“Between the Families” – Artifacts as Representations of Identity : Locket

“Between the Families” – Artifacts as Representations of Identity : Locket[Download Handout for students]

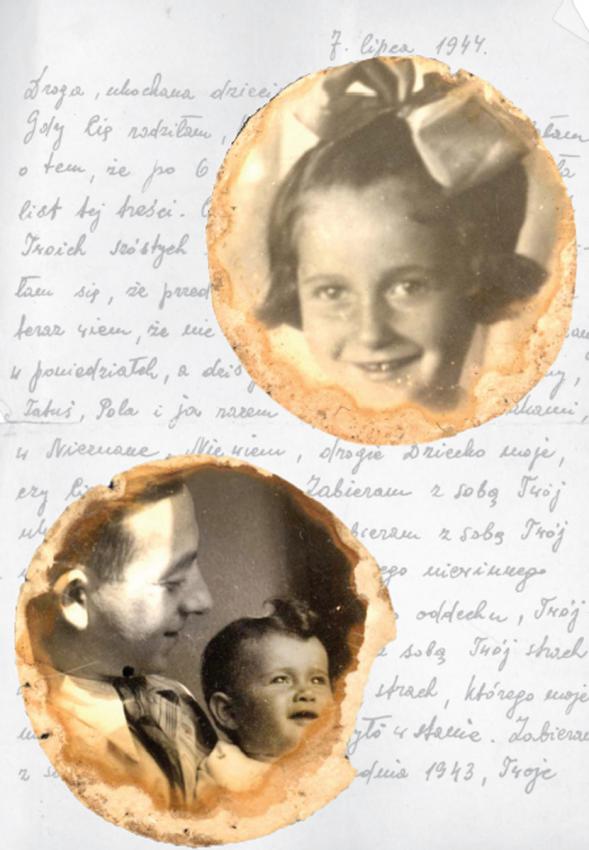

Under similar circumstances to Marta Goren, Dita Gurlitz received a locket that symbolized parting, identity and family all at once, but for her and her family a different fate awaited, and so the pendant assumed a unique meaning. Sarah and Yechiel Gurlitz of Bedzin, Poland, brought Dita, their only daughter, then six, to a Polish friend. Sensing that they would not return to see their daughter, they left her with a locket containing a picture of her and them, along with a letter she was to read when she was older.

My beloved little girl, more precious than anything,

When I gave birth to you, my beloved, I never thought that after six-and-a-half years I would be forced to write you a letter like this. I saw you last on your sixth birthday, on 13 December 1943. I was under the illusion that I’d see you again before we left, but now I know that will not happen. I don’t want to endanger you. We are traveling Monday and today is Friday evening […] I take with me your lovely image, as you were in our home, your cute childish voice, the scent of your pure body, the pace of your breathing, your smile and your cry; I take with me the vast fear and terror that a mother’s heart is not capable of forgetting for even one moment… remember well your honored grandmothers and grandfathers, your aunts and uncles and the whole family. Guard the memories of us all please, do not blame us. As for me, your mother, forgive me, forgive me my dear child for giving birth to you. My intention was to bring you into the world in your community and live your life, and if things turned out differently, it is not our fault; therefore I plead, my dear little and only chick, do not blame us. Try to be good like your father and forefathers, love your substitute parents and their family, who will certainly tell you about us. I want you to value how much they are sacrificing of themselves of their own will. Another thing I want you to know, is that your mother stood tall, despite all the humiliations that befell us from our enemies, and if she is to die, she will die without condemnation, without crying, rather a smile will cross her lips in scorn of her hangmen.

I grasp you to my heart, kiss you passionately, and bless you with all the strength of a mother’s heart and love. Your mother.

3

To her great fortune, Dita's parents survived, and they all made Aliyah.

Both Marta's pendant and Dita's locket symbolize separation and connection, and take on distinctive meanings that range between the personal and the familial, as well as their natural identity and a new identity the girls were forced to assume while hidden with their rescuer families.

Hope and Connection: Anny and Pawel

Hope and Connection: Anny and Pawel[Download Handout for students]

Artifacts are usually kept by people as a souvenir and a symbol of a connection. During the Holocaust, when connection to family and beloved ones often became impossible, the artifacts held added meaning, and holding onto them bestowed strength and hope.

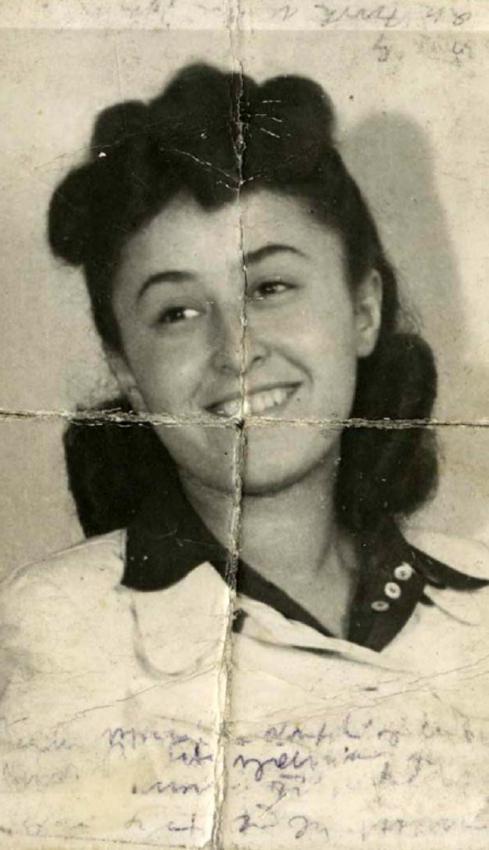

In September 1944, for the first time, two transports consisting of only young people were sent from Theresienstadt. Anny and Pawel, who had met and become friendly in Theresienstadt, married hurriedly three days before Pawel was deported to Auschwitz, in the hope that it would make it easier for them to find each other later on. Shortly before he was deported, Anny give Pawel her photograph and wrote an inscription on it.

A few days later, together with many of the wives of the young people who had already been deported, Anny, her sister and mother volunteered to join the transport, on the basis of a false promise that had been made to them, that they would be reunited with their loved ones.

In an interview, Pawel described his arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau:

"We took off our clothes. Took off everything. There was absolutely nothing left on us. I kept one thing with me – a photograph of my wife Anny, who I had married just three days earlier (in Theresienstadt). I folded the photograph so that it would be very small and… put it into my mouth. I carried the photograph with me everywhere until the end of the war. I hid it in clothes and pockets, depending on what I was wearing. The photograph was a kind of fetish, an object of worship, a type of mezuzah, or amulet; something that connected me to life outside, to normal life. I was romantically connected to Anny, a connection that was very complex, but that photograph was a piece of normality."

Hope and Connection: Paula Fried

Hope and Connection: Paula Fried[Download Handout for students]

Paula (Pessi) Fried was born in Munkacs in 1926, the second of five children. In 1944, she and her family were deported to Auschwitz. Pessi was separated from her family in a selection and sent to work in the “Canada Commando”, where the luggage that Jews brought to Auschwitz was gathered and sorted. One day, another prisoner who also worked at the sorting facility approached her with an envelope containing seven photos of Pessi and her family, photos that her family members apparently brought and which were taken from them, along with all their other belongings, as they reached the camp.

In one of the photos, Pessi’s younger siblings can be seen – Moshe-Aharon, Tzipi and Eti – outside their home in Munkacs in 1941. All three of them were murdered.

Pessi wrapped the photos in a piece of cellophane, on which she spread margarine and then inserted between two slices of bread. In this way she kept the photos safe even in other camps to which she was sent, until her liberation.

Hope and Connection: shirt

Hope and Connection: shirt[Download Handout for students]

Shmuel Daich was imprisoned with his family in the Kovno ghetto. Together with his father Menachem Mendel he worked at forced labor, building an airfield outside the ghetto. One day, when they returned from the night shift they saw an aktion taking place in the ghetto, with residents standing in two groups in the town square. Menachem Mendel, realizing what was happening, decided to divide his large family into smaller groups so that they would go through the selection separately as he quoted: “The camp which is left shall escape.'” (as learned from the biblical story of Jacob and Esau in Genesis 32:8-9). Shmuel, aged 18, Chaya Fruma, aged 17, and their younger brother Yitzchak, aged 2, stood together in a group. In his final words, his father requested that Shmuel serve as a father to the children. Following the aktion, Shmuel, Chaya Fruma and Yitzchak returned to their home. The rest of the family was transferred to the “Ninth Fort”, where they were all murdered. Shmuel found protected work as a shoemaker in the ghetto. He joined the “Shomer Hadati” movement and the “Zionist Covenant” underground, which acted in the ghetto to provide goods to the partisans active in the forests surrounding Kovno. Despite harboring many doubts, and although he felt responsible for his siblings, Shmuel decided, with the encouragement of his sister and cousins, to leave the ghetto and join the partisans, to increase the chances that someone from the family might remain alive. At the end of the war, Shmuel was the only member of his family to survive.

Before leaving the ghetto, his sister Chaya surprised him with a gift – a shirt on which the Tablets had been sewn in blue thread, with the initials of his name, S.D., and said to him: “The two Tablets will be near your heart… you are joining the Red (communist) partisans whose war is also against religion…” Shmuel left the ghetto with a pistol in one pocket and his tefillin in the other.

He did not remove the shirt he received from his sister the entire time he fought with the partisans. Even after liberation, while fleeing from Lithuania to Romania, he did not remove the shirt, which symbolized for him his obligation toward his heritage and identity, and which was the last item remaining from his family. When he later wed, he wore the shirt under the chuppah.

These artifacts, like others carried by those torn from their families and who were sent or fled to the unknown, later became the last connecting thread with their families and were a source of strength and hope.

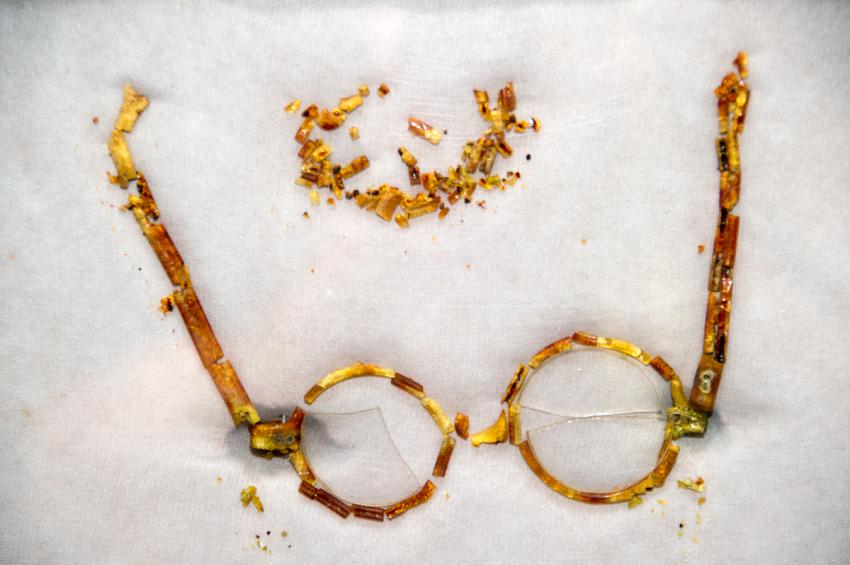

Artifacts as Memory and Testimony: 1. Glasses

Artifacts as Memory and Testimony: 1. Glasses[Download Handout for students]

As stated, during the Holocaust objects often took on a meaning entirely unrelated to their functional purpose. This, for example, was the case with Bluma Wallch’s glasses and Hinda Cohen’s shoe.

Tula Wallach was about sixteen years old when the Germans occupied Lodz. A short time after the occupation, her father and two brothers fled to the east. Although her mother implored her to join them, Tula refused to leave her sickly mother alone and remained at her side in Lodz.

The mother and daughter experienced four and a half years of hunger, yearning and despair together in the Lodz ghetto as they took care of one another, constantly in fear of deportation and separation, the fate of so many.

In August 1944, when the Lodz ghetto was liquidated, Tula and Bluma were deported to Auschwitz. Tula described the journey to Auschwitz in the train car:

Late at night, I got down on the floor. I sat down next to my mother and her thoughts were ever so clear, because during all the years, we had worried so much about Father and my brothers and knew nothing of their fate. We knew that they had fled to Russia and that they didn’t know what had happened to us. She was so ill and miserable and wretched, and I desperately wanted to help her. But I had no way to do so.

Upon their arrival at Auschwitz, despite Tula’s attempts to remain at her mother’s side, they were forcibly separated and Bluma was sent to her death. When Tula was forced together with all the other women to undress and hand over all her valuables, she removed the ring her mother had given her from her coat pocket along with her mother’s reading glasses that she happened to have with her. She threw the ring on a pile of objects, but kept the glasses, claiming she needed them to see. A short time later, she found a piece of rope, which she wound around her body and on which she hung the glasses.

Tula relates that although she knew she would never see her mother again, she continued to search for her even after she was transferred to another camp.

When the war ended, Tula was among the few that survived. She eventually immigrated to Israel, where she raised her own family. Some fifty years later, Tula Meltzer came to Yad Vashem and decided to donate her mother’s glasses to the museum. She explained her actions thus:

I have brought them to Yad Vashem because I had them for many years, and from time to time, I would open up the package to look at them, broken and falling apart, and each time the pieces were smaller. I couldn’t fathom what would happen if I died, and my children took the pieces and threw them away. Each time, there were fewer pieces, until I decided to bring them to Yad Vashem.

4

The glasses are currently displayed in Yad Vashem's Holocaust History Museum

Artifacts as Memory and Testimony: 2. The shoe of Hinda Cohen

Artifacts as Memory and Testimony: 2. The shoe of Hinda Cohen[Download Handout for students]

Zipora (Tzipele) and Dov (Berka) Cohen were a young couple when they were taken, together with their young daughter Hindele (Hinda), to Aleksotas, outside the Kovno ghetto. Hindele was only a year old and had been born in the ghetto after Zipora lost her first pregnancy. Tzipora and Dov were brought along with a thousand other prisoners to do construction work in an airfield. In Aleksotas, the women and children were separated from the men, and Zipora and her daughter went to sleep each night hugging each other and crying in longing, fear and hunger. In the morning, the grownups were taken out to work while the children remained behind in the care of a handful of adults and elderly people.

The morning of March 27, 1944 was different. Instead of doing their regular work, the women were sent together with the men from the camp’s back gate to work in the airfield performing hard labor that did not appear to have any visible purpose. Everyone could sense that something was imminent and when the Zipora and Dov returned to the camp in the evening, they were stunned to discover that their daughter had been taken, never to return. After the adults had left for work, a children’s Aktion began, during which the 300 children of the camp were deported by train to Auschwitz, where they were murdered immediately upon their arrival. Hindele, who was only two years old at the time, was snatched from her bed ill with chicken pox, covered only with a blanket that the woman taking care of her had managed to wrap her in at the last moment.

Dov and Zipora stood shocked and bewildered at the sight of their little girl’s empty bed. Under the bed, they found one of her shoes along with a pair of mittens that Zipora had knitted for her. Dov took the shoe and etched the date of the Aktion on its sole, swearing to safeguard it for the rest of his life.

Later in the war, Dov and Zipora managed to escape to the forest. They were liberated by the Red Army and in 1947 had another daughter. They immigrated to Israel in 1960.

At their request, their grandchildren delivered little Hindele’s belongings, which Dov and Zipora had safeguarded their entire lives, to Yad Vashem.

Religious objects also received added significance in addition to their traditional function.

Artifacts as Memory and Testimony: 3. Tefillin

Artifacts as Memory and Testimony: 3. Tefillin[Download Handout for students]

Chaim Basok grew up and was educated in Vilna. He was a yeshiva student and a member of the Bnei Akiva religious youth movement. One Sabbath evening in 1943, at the age of 20, he left the Vilna ghetto and joined a partisan unit. On the events of that Sabbath evening he relates:

My mother lit Sabbath candles and wept.

My grandmother lit Sabbath candles and wept.

My sisters wept.

The aunts wept.

Everyone wept.

My heart was quietly distraught.

Everyone knew I was leaving them.And maybe it will be forever.

I am in the first group escaping this evening from the ghetto. On the way to the partisans.

I prayed 'Kabbalat Shabbat' […] I ate my mother’s cooking for the last time and each bite of the challah got stuck in my throat and choked me.

I put my tefillin in my left coat pocket and my pistol in my right coat pocket. I said the blessings quickly. My mother hugged me, her tears sticking to my cheeks, which I feel until today, they will not leave me […]

Chaim left for the forests. At first he was a member of the Jewish partisan unit “Nekama [Revenge],” and later he joined the Lithuanian division, taking part in daring raids in which they attacked German police stations and laid mines for trains.

“In the left pocket of my coat – my tefillin, in the upper right pocket of my shirt, my small book of Tehillim [Psalms] that I never abandoned” – throughout his stay in the forest he carried his tefillin with him and took care to use them.

At the end of the war, Chaim joined the “Bricha” organization and was active in organizing Youth Aliyah. He himself made Aliyah, married, and established a family.

When his eldest son reached bar-mitzvah age, Chaim stood before the assembled guests who had come to celebrate and read the passage from the Book of Ezekiel about the vision of the dry bones. As he read the words he began to cry, as did his friends who had fought beside him as partisans. “After the Holocaust, all of Europe was full of bones. We remained alone, beaten and bruised, wondering, could this nation be revived? All who remained are alone, beaten and bruised – can we rise up and return to life?”

Chaim continued, citing a discussion in the Talmud between sages regarding the question –did Ezekiel's vision actually happen as stated, or is it just figurative? "Rabbi Eliezer says: The dead that Ezekiel revived stood up and recited a song to God and then returned to the dead… Rabbi Eliezer, son of Rabbi Yosei HaGelili, says: Not only was it not a parable, the dead that Ezekiel revived also ascended to Eretz Israel and married wives and fathered sons and daughters. Rabbi Yehuda ben Beteira stood up and said: I am a descendant of their sons, and these are phylacteries that my father’s father left me from them" (Sanhedrin 92b).

Chaim continued, saying: “Will the day come when people ask whether the Holocaust really happened?”

“I”, he said, pointing to himself, “made Aliyah and married a woman and here are my children”. Then he took out the tefillin he received from his father Ezekiel, which he put on each day in the forests, and gave them to his son Ezekiel.

"The day will come when you will be asked if this really happened. You should say to them: These are the tefillin that my grandfather Ezekiel put on my father and gave to him, and he put them on me and gave them to me. They are my witnesses”.

After 25 years, when his grandson Alexander was celebrating his own bar mitzvah, the boy stood before his grandfather Chaim and the entire family, and said: “My father told me the story. Grandpa, I promise you that if the day comes and I am asked, I will tell them, I will also tell my grandchildren and they too will know to say – it really happened" .

The glasses and the shoe both underwent a transformation from private, functional possessions to artifacts of familial remembrance, and ultimately public remembrance. What was lost and added in this process is in large part a product of the attempt to fill the deep void that remained. By its very survival, the tefillin became a symbol of continuation during and after the Holocaust, yet also served as testimony in a world in which meeting with the survivors themselves will no longer possible.

After the students have studied the artifacts and shared the stories with the rest of the class, have a discussion on the following questions:

- Did the artifacts retain their original function?

- How do the stories of the artifacts reflect the upheaval the Jews experienced in the Holocaust and how do they express a grasping for values and continuity?

Summary

SummaryThe writer Yehiel Dinur, who lost his entire family in the Holocaust, wrote:

Give back

Give me back just one single hair of my sister’s golden curls!

Give me back one of my father’s shoes;

A broken wheel from one of my little brother’s skates

And one speck of dust resting on my mother’s back…

In light of the poem "Things" and the encounter with the artifact stories, we can better appreciate Dinur’s poem.

The desire to touch something tangible that belonged to one's family that is no longer only grows stronger when there is no grave or gravestone one can visit. Touching an artifact seemingly enables a connection with a father, mother, siblings, and their memories. The artifacts in these stories fulfilled this need, sometimes for the person receiving the artifact and sometimes for the person who gave it. With this, holding a particular artifact expresses the depth of the rupture and the large void that the family attempted to fill, even a tiny bit, and the natural attempt to feel part of the family, a feeling that is an essential element in one's identity and significant anchor in dealing with the Holocaust and its aftermath. Alongside the rupture expressed by the artifact, its very presence enables transmitting the memory of lost family members to the next generation.

_with_her_parents.jpg?itok=4LwJnEWR)