Lesson Objectives and Educational Emphasis

Yad Vashem was established to perpetuate the memory of the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust. One of Yad Vashem’s principal duties is to convey the gratitude of the State of Israel and the Jewish people to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. This mission was defined by the law establishing Yad Vashem, and in 1963 the Remembrance Authority embarked upon a worldwide project to grant the title of Righteous Among the Nations to the few who helped Jews in the darkest time in their history

The Righteous Among the Nations were not "born" for their historic task. They were ordinary people from all walks of life who, within an atmosphere of indifference, hostility and even collaboration, made a fateful decision out of commitment to their values and at great risk of persecution by a cruel regime of terror. Their choices, though made under extreme conditions far from our everyday existence, have great educational significance today, as they prompt a deeper discussion about the ability of human beings to make choices and the inherent power of these choices both for the individual and for the masses.

The process, which for many began with a decision reached in an instant, became over time an obligation and often turned into a deep connection with the victims. It also placed a heavy burden of responsibility replete with long-term dangers that changed their lives. It is important to stress that these people, who acted upon a different moral code than those in their wider society, were a small minority. Often this act of righteousness was accompanied by isolation: It was impossible to trust anyone even minimally; it was impossible to know who would support and who would betray, who could keep the secret and who would reveal it, even unintentionally, with a word or a glance. In most places, the act took place within an atmosphere that ranged from indifference to hostility, and in many cases, even active collaboration in dispossessing and murdering Jews. Therefore, the price of rescue was not only isolation, but also a matter of life and death, with threats from the German regime as well as from local populations.

Were they angels?

It's important to bear in mind that often in the accounts of Righteous Among the Nations are liable to leave the impression that these people had "angelic" qualities, unlike other people. This carries an educational risk. When these Righteous are perceived as "angels," we cannot learn from their actions. We must therefore emphasize again and again that we speak of regular people who heeded the call of their conscience and found within themselves compassion and sensitivity and the courage to act upon them. They succeeded in viewing the persecuted Jews as human beings, sometimes because they knew them but mostly they were strangers until that point. These Righteous, like others, had good characteristics and less good ones, and sometimes even held worldviews that made it unclear or unnatural that they would sympathize with Jews, but in their hour of need, they chose humanity.

If so, the focus of the educational discussion should be to pose complex questions even if some will remain unanswered. What caused a regular person to become a Righteous Among the Nations? How could it be that from amongst a group of people, a few acted on behalf of others without having any special personality traits or uniform value system? Is it possible to pinpoint a specific moment or event that convinced them to extend aid to a persecuted Jew?

While it is challenging to find a unifying characteristic in the stories of the Righteous Among the Nations, it appears that common to all was an ability to perceive the Jews as people – despite a reality in which Jews were dehumanized, hated and killed as a result of racist, antisemitic ideology. The stories of the Righteous, if so, enable us to discuss the human ability to see the good in others; the ability to stand up for principles against a world from which they were alienated; and the far-reaching implications of humanity's ability to choose. It's important to remember that the Righteous Among the Nations were a very small minority within the population. This lesson focuses on the successful attempts to save Jews, but in many cases rescue attempts ended in failure – and in the murder of the Jews and their protectors alike.

Lesson Structure

- Through Their Own Eyes – viewing testimony

- Stories of Righteous Among the Nations – group work

- What made them different from their fellow citizens? – summary discussion

Lesson presentation

Lesson presentationThrough Their Own Eyes – viewing testimony

Through Their Own Eyes – viewing testimonyView the testimony.

- What challenges and difficulties did Jews face during the Holocaust when attempting to hide or flee persecution?

Many Jews who survived during the Holocaust did so with the help of non-Jews who risked their lives, such as Leopold Socha, as told by Kristine Keren in her testimony. In the beginning, the Jews hiding with Socha and his wife paid their benefactors, but eventually the money ran out, and the couple continued to care for the fugitives paying, together with the Wroblewskis, for the food out of their own pockets.

Rescue during the Holocaust presented dilemmas both for the rescued as well as for the rescuers. Discussing these dilemmas within the context of the Holocaust is essential to understanding the stories of the Righteous Among the Nations.

In this lesson we focus on the Righteous Among the Nations – what motivated them to help Jews at such great risk to themselves? What difficulties did they face? And what was the significance of their actions?

Stories of Righteous Among the Nations – group work

Stories of Righteous Among the Nations – group workThe objective of the group work is to become familiar with a story of Righteous Among the Nations and the Jews they saved. The stories differ from one another mainly by the types of rescuer: women, men, farmers, intellectuals, those with anti-German political leanings, and others. Each of the rescuers in these stories fulfill the criteria determined by Yad Vashem to qualify for the title of Righteous Among the Nations, and each has been formally recognized as such for their activities during the Holocaust. Becoming familiar with the personal stories of a rescuer as well as those saved allows for in-depth learning and enables us to understand the phenomenon of Holocaust-era rescue not only from a historical dimension, but also from a personal and human one, which is at the heart of this chapter.

Having each group study a single story and present it to the whole class at the end facilitates discussion about the phenomenon of rescue rather than the specific story.

- Group 1: Story of Tamara Nikolayeva from the village of Zagromotye, Leningrad District, USSR

- Group 2: Story of Janis and Johana Lipke from Riga, Latvia

- Group 3: Stories of Julius Madritsch, an Austrian industrialist, and his loyal assistant Raimund Titsch, who saved Jews in the Krakow area in German-occupied Poland

- Group 4: Story of Andree Guelen-Herscovici from Belgium

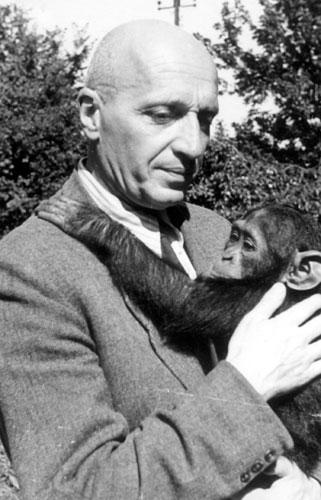

- Group 5: Story of Jan Zabinski, head of the Warsaw Zoo, and his wife Antonina

- Group 6: Story of Dr. Ella Reiner-Lingens and her husband Kurt, from Austria

- Group 7: Story of Maria Olt, Hungary

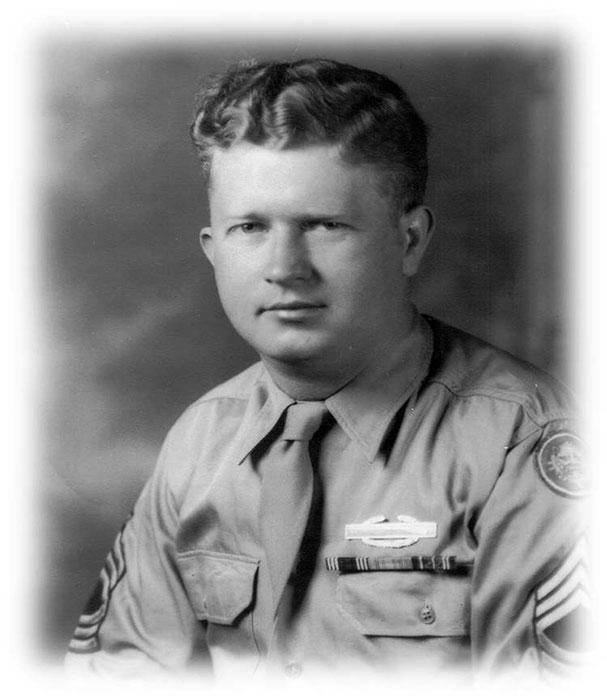

- Group 8 : Story of Roddie Edmonds, USA.

The summary discussion for all participants will be based on identical questions:

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated the act of rescue?

- Describe the rescuer/s: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did the rescuer/s face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision, or was the rescuer faced with making the decision several times? If the latter, can you identify the points at which the decision was renewed?

Group 1

Group 1[Download Handout for students]

Tamara Nikolayeva (USSR)

"Turn over the child," the village head implored.

"I will live – and the child will live. If we die, we all die. We won't escape our fate," answered Vasily. Vasily's daughter Tamara was deeply worried about the well-being of Marek, the Jewish child in her care. The Feldman couple, for whom Tamara had worked as a Nanny, had entrusted her with their infant son Marek, whose life was in danger only because he was Jewish. Tamara could not reconcile herself to this fact. She felt obligated to the child, his mother, and his family. Her parents agreed with her, and this obligation became a family one.

The story began way before the Germans' arrival. Before the War threatened to destabilize everyday life in Leningrad and the small village of Zagromotye in the Leningrad district, USSR, Tamara had moved in with the Feldman family, working as Nanny for their newborn child. Frieda, Marek's mother, was pleased with Tamara, and Tamara soon became attached to the family. In the summer, when families typically left the city to vacation in villages, Tamara invited Frieda to her own village. For Tamara, it was natural that Marek should spend the summer in her village. In the summer Frieda, Marek, and Marek's grandmother Chana visited Tamara's family. The village was a nice change from the big city. The food was good and the air fresh, and Tamara's family, who were warm and friendly, welcomed them as if they were related. When they parted at the end of the summer, the Feldmans promised to return the following summer.

Days passed, autumn arrived and then a difficult winter. Everyone pined for the warm summer. At the onset of the following summer, the Feldmans kept their promise and returned to Tamara's village. The vacation began like the previous ones, but ended with the start of a terrible war. At the time, village residents had no idea a war was brewing, that shortly the lives of the Feldmans would be entirely upended, and that Tamara would need to make the most difficult decision of her young life, one which would place herself and her family in the path of unimaginable danger.

When the war began, Marek and his grandmother Chana were in Tamara's village, while Frieda was at home in Leningrad. The Germans began to bomb the region. There was no quiet, not even for a moment. Fear ruled, and no one knew what the next day would bring and what sort of war awaited them. The Germans, it was said in the village, would not surrender quickly, even against the mighty Red Army. Everyone had heard about the Germans, how they invaded European cities and conquered them one by one, without mercy. Chana was helpless to formulate a plan. Where could she go with a two-year-old boy when all the roads were being shelled? How would they return home? And what would become of them there? In the end, a decision was made: The boy would stay in the village without his mother or grandmother, but rather with Tamara and her parents, who promised to take care of him as if he were their own. Frieda repeatedly attempted to return to the village to collect her son, but this was already impossible; all the paths were blocked by the ever-advancing front. After a short time, the entire village was occupied by the German Army. To all, Tamara presented Marek as her own son.

Nevertheless, the head of the village, who knew the true identity of Marek, soon requested that the child be turned in. Why should the village risk giving refuge to a Jewish child? He even threatened Tamara's father, but despite this, Vasily did not turn in the boy. The other 80 village inhabitants, all of whom knew that Marek was not Tamara's child but rather a Jewish infant from the city, refused to comply with the village head. Had any of them informed on his presence, Marek, Tamara, her family and the entire village would have been endangered. Days passed, and Tamara took care of Marek like a treasure entrusted to her. For her, this was natural and obvious behavior. Tamara's parents managed to get a letter to Frieda, on which was written, "We will do everything to save your son's life." Frieda missed her son intensely, but knew he was in good and loyal hands.

From time to time, rumors spread that the Germans were kidnapping Russian youth and sending them to work in Germany. Tamara was very fearful. "If I am caught, what will become of Marek? What will become of my parents?" she wondered. She managed to evade capture several times. Then Vasily died. Along with the pain and grief of losing her father, she felt that the responsibility for the child's welfare had fallen solely on her. By no means, she thought, would she ever allow herself to be taken away from the village. In the meantime, some of the locals were preparing hiding places in the nearby forest. Tamara joined them. She had to have a hiding place, for her own sake and for Marek's. And indeed, each time the Germans neared the village, she grabbed little Marek and ran with him to the forest, to Zemelyanka, to wait for the threat to pass.

The war did not cease. Although more rumors spread, this time that the Germans had started to retreat, and people praised the Red Army, they also heard that the Germans were setting each village ablaze as they left it, as well as its residents. In the winter of 1943 and with the start of the New Year, the Germans began to retreat from the region; Tamara's village was set ablaze. Village residents resisted the Germans and were injured from enemy fire. Two months later, the yearned-for liberation day finally arrived. Now the lives of Tamara, her mother, and little Marek were no longer in danger. But what had been the fate of the Feldmans? Leningrad had been under an unbearable siege, and suffered a lack of food and water for 900 days. What had become of them? Did they survive? Eventually a letter came from Leningrad. Tamara wrote back to them, and carefully sketched an outline of Marek's hand on white paper to give Freida a sign of life and some joy.

In the fall of 1944, Chana and Freida stood at the entrance to the village, their arms outstretched to hug little Marek and Tamara, their personal redeemer.

Shortly afterward, Tamara married. Sadly, she was unable to bear children herself, and her only "son" was Marek. Each summer the Feldman family would continue to visit Tamara, and Marek, his wife and children run to greet her and call her "grandmother."

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Tamara Nikolayeva to help the Feldman family?

- Describe Tamara: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did Tamara face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps was Tamara called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 2

Group 2[Download Handout for students]

Janis and Johanna Lipke (Latvia)

When the Germans occupied Latvia in the summer of 1941, the atmosphere in the city was especially supportive. Cries of joy and happiness accompanied the convoys of soldiers entering the city. For many Latvians, this was a sign that perhaps they would gain independence through Hitler, and thwart Stalin's desire to incorporate them into a Soviet bloc. In newspapers and on the radio, calls went out to "beat the Jews and the communists"; and Latvian citizens, led by volunteer collaborators with the Germans, struck out at their Jewish neighbors. Jews were hunted, murdered in the streets or brought to nearby forests to be killed. Latvian residents of Riga went from house to house, pointing out Jewish homes. The reality for Jews became unbearably difficult.

Before the war, Janis Lipke worked at the port in the city, performing difficult physical labor for which he was poorly compensated. There he began to smuggle goods, a skill that served him well later when he was called upon to smuggle people. He saw the injustice done to the Jews, felt the unfairness with which they were treated and heard the voices crying for help amidst the unruly, indifferent crowds. His son, then eight years old, remembers his father standing with tears in his eyes in front of the barbed-wire fence separating their seemingly normal world from the Jewish death trap, crying and ordering his son, "Look, son, and never forget." The son looked at his father and absorbed from him a love of humanity and the ability to worry about others.

Once new positions opened up to Latvians, Janis was appointed foreman of the civilian unit that worked for the German Luftwaffe (air force). His workers came from the new ghetto that had been formed to house the few Jewish people who had survived the bloody events accompanying the start of the occupation. Each day, Janis would enter the ghetto to take charge of Jewish workers exploited by the Germans. Among them were many who wished to escape. Janis turned a blind eye to them. To make up for the missing numbers when they returned to the ghetto, he convinced loyal friends, Latvians, to re-enter the ghetto in their stead, wearing a yellow star, and the next morning to join the ranks of Latvians who came into the ghetto as foremen, like Janis himself. Janis opened an escape route for Jews, a route to life. Janis also approached Jewish workers and acquaintances and said to them "Set up hiding places within the ghetto, and in times of danger hide there for a day or two. Afterwards, I will come and take you out." In December 1941, Janis managed to smuggle his first group of ten Jews out of the ghetto, with help from a trusted friend and confidante, the driver Karlis. The Jews were hidden in the truck, under logs and other goods. Thus Janis, the former goods smuggler, became an expert smuggler of people. In the freezing cold, he dug a hiding place in his house, and was always looking for additional hiding places for Jewish fugitives.

In the summer of 1942, a revolutionary plan formed in the mind of Janis the people smuggler. He bought a sailboat with the goal of reaching Sweden, the neutral country on the other side of the Baltic Sea, where Jews could live without fear. But the plan to reach safe haven there failed after the government became suspicious and Janis was caught with Sasha Perl, a Jew smuggled from the ghetto and with whom the plan was formed. Janis managed to bribe his captors and secure his own release. However, his efforts to bribe Perl's release were unsuccessful: Perl was murdered. Janis realized he was in grave danger, and took upon himself to relocate the Jews hiding in his home. He fervently checked for alternative hiding options that could accommodate such a large number of people. The fear was great – not only were he and his workers at risk, but also his wife and son. He acquired a farm in a small village called Dobleh, not far from Riga, and located Latvian farmers who agreed to help him save the few Jews who had survived the horrible murders. Janis brought the Jews who had been hiding in his house to the farm, as well as other Jews.

Over time, the Germans turned the Riga ghetto into a full-blown work camp, where Jews worked in forced labor for many hours. Janis went around the barbed-wire fences, whispering to Jews to come near, speaking to one, providing an encoded address to another. He encouraged escape, provided them with clothes underneath rags marked with a yellow star, offered them money and jewelry that Jews had given to him to distribute, so that they might bribe guards. The name "Jan" became a sort of magic word. Some of the prisoners doubted whether he really existed.

One girl passing along the barbed-wire fence met Janis and received an apple. She was so excited that she caressed the apple and put it close to her cheek, but did not eat it. "Are there more apples?" she asked Janis. He answered that he had a garden full of apples and promised to take her there. He wrote a note to the girl's mother: "Prepare yourself and your child. I'm taking you out of here." By the time Janis managed to arrive, the mother and daughter, Sofia and Chana Stern, Jews who had been brought to Riga from Germany, had already been taken to work at a different camp. Janis managed to reach this camp and explain to the mother how to escape. Once they had, he collected them and brought them to his farm. Chana received a coat from Janis's wife Johanna, a welcome act of humanity. Janis met with another 12 Jews and arranged an escape date. One of them told Janis that sadly, he had no way of paying. Janis responded angrily: "If you think I'm doing this for your money, know this – you don’t have enough money to pay for my life." One successful operation begat another. Not every mission succeeded, and there were sometimes casualties. Janis was surrounded by murder, violence and indifference, and nonetheless continued to hatch various escape plans until liberation.

On 13 October, Riga was liberated, as were the Jews saved by Janis Lipke and his wife Johana. Of the approximately 100 Riga Jews who survived the war, 42 were saved thanks to Janis.

One day an envelope arrived at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem with a Riga postmark. Inside was a 30-page typewritten manuscript in Russian. This manuscript, emotionally written by R. Zilberman, a Riga resident, contained the reminisces of 17 survivors. On the heading of the first page was the prominently displayed title: Jan Lipke – A Story Documenting an Exceptional Person.

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Jan Lipke's act of rescue? What aspirations for saving others appear in this account?

- Describe Janis Lipke: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did Janis face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps was Janis called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 3

Group 3[Download Handout for students]

Julius Madritsch and Raimund Titsch (Poland)

Julius Madritsch arrived in Krakow after doing everything in his power not to be drafted into the German Army. Madritsch was a Viennese youth who was meant to join the army like anyone else his age, but he attempted to avoid serving Hitler's ideology or Nazism in any way. At the end of 1940, he breathed easier as he successfully reached Krakow as a textiles expert. In December, he took on management of two factories, a position to which he was appointed by the Economic Ministry of the Generalgouvernement. There he met Jews, and this meeting transformed him from a draft-dodger who opposed the government to a man who externally identified with the German government but privately risked his life to save helpless Jews.

From the beginning, the Jews in his factory sensed that they were dealing with a different type of German, one who was not hostile. Madritsch immediately promised to work for their welfare, and in return, he earned their trust. It was not easy to place trust in a German. At first, orders were slow to come to the factory, but with the help of the right connections, the orders began to flow in. At this point, a surprising line of communication opened – Madritsch connected with members of the Jewish community to supply textile workers from the ghetto. The Judenrat (Jewish ghetto leadership) was enthusiastic, as its mission was to supply as many factory workers as possible, especially those factories whose working conditions were good. Jewish work groups were formed and Madritsch supplied them with prized work certificates from an employer that declared them "essential to the war effort"; in other words – they needed to remain alive.

Madritsch's trusted assistant was a fellow Viennese named Raimund Titsch. His formal title was work manager at the two factories that had been established, while his underground title was confidante and aide to the factory's Jews. When Madritsch received another draft notice in April 1941, he understood how much he was already in the midst of his own personal war. The Jewish factory workers had become a closed group that very much needed him. He was often reminded by his Viennese friends and others that he was to bring only temporary workers into the factory. They threatened him indirectly that he was "sabotaging the expulsion of the Jews," and warned that he would run into trouble with the Gestapo. But Madritsch continued on his mission, taking on more and more Jewish workers, worrying about their welfare and refusing to disengage from them. Over time, some 800 Jews worked at each of his factories. His responsibility was great, and he had to surge forward, working against his longtime friends and acquaintances, as well as the formidable Nazis surrounding him.

In March 1943, the Germans violently and mercilessly closed the ghetto and gathered its residents in the public square, where they performed a selection. In doing so, many were murdered in the streets. "Madritsch and Titsch are here," whispered voices heard. Workers heard that the two were wandering the ghetto, as if from curiosity, standing indifferently and watching the expulsion, when in actuality they were looking for their workers, to bring them to the factory and take care of them. They were able to transfer 300 people to an additional factory in Tarnow, where it was relatively quiet, and from there many fled to Slovakia.

Madritsch's connections with another Viennese citizen, Oswald Bosco, helped him act. A few Jews managed to avoid expulsion, and afterwards hid, frightened and entirely dependent on the kindness of others. Bosco, whose formal role was head of the German police in the ghetto, was a trusted helper of Jews and brought many of them to the factory. He did not bring all of them in one day. At tremendous risk of paying the ultimate price, over the course of ten days he transferred Jews, including children who were given sleeping pills and brought over in large sacks. Madritsch received the transferred Jews, but needed to hide them, as their presence threatened the lives of all his official workers, as well as his own. He was eventually able to find a Polish family to temporarily take some of them in. Again, their objective was to escape into Slovakia, and some succeeded. Bosco, however, was captured. He tried to run to the mountains and pose as a priest, but the Germans, who knew what he had done and considered him a traitor, recaptured and killed him.

Even after the great expulsion, Madritsch's troubles continued. One day, an order was published stating that Jewish workers would only be allowed to work in munitions factories, and the permit for receiving workers would be granted exclusively by the SS. Madritsch, concerned, managed to contact an acquaintance and obtain the permits. Thanks to his background, he was familiar with German attitudes and understood their language. Madritsch bought more and more sewing machines. Each sewing machine justified hiring more workers; three workers were on each machine, not for the sake of economic profit but for human benefit. Those working at his factory were the lucky ones from among the camp's Jews. A year after liberation, a number of Jews saved by Madritsch wrote him a letter: "The truth is that we should thank you for many moments of lightness. At a time when Jews lost their basic human rights you were more for us than just a regular person … all the prisoners of the camp that could work in your factory were the lucky ones, and your sensibilities enabled you to find ways to protect us from many dangers." Over time, the nickname "Madritschim" stuck to describe the lucky ones who were entirely dependent on the kindness of this stranger who believed with all his heart in the triumph of justice. Madritsch took care of their sustenance, and the ration of bread supplied to each employee was big enough that some were able to sell it in the black market in exchange for a sausage. Most of the food smuggling into the Plaszow camp, known by the prisoners as "Smugel," was done via Madritsch and Titsch's cars, under piles of fabric. Madritsch knew this and all he asked of the Jews was that they be careful. His factory even had a kosher kitchen, and the cook who oversaw it was an observant Jew named Akiva Eisen.

During this entire time, Madritsch and Titsch lived in great fear of having their double life exposed. They feared not only for their own, but also for those who looked into their eyes and pleaded for help. Titsch became friendly with several of the workers and passed along news about the war's progression that he heard on the radio, signs of life from the outside world, bringing hope that maybe this terrible nightmare was close to ending. One day the doctor Chaim Veksel, who worked in the factory, received many zlotys from Titsch. It turned out that on the day the Tarnow ghetto was liquidated, Veksel's father handed Titsch US $100 to pass on to his son. Carrying and exchanging US dollars was dangerous, so much so that anyone caught doing so would be killed, even if they were German. Yet Veksel received his money, as Titsch did not refuse the request of Jews. Titsch would consult with Veksel on medical issues, and speak to him as an equal. The Jewish doctor never forgot this.

In the end, the Germans overwhelmed the Jews of Plaszow. In the framework of the camp liquidation, the Plaszow camp was also liquidated and its Jews sent to other camps. Madritsch did not believe that he had any more power to help the Jews and felt that things had reached a dead end. With great sorrow and pain, he parted from his Jewish friends.

- What motivated Julius Madritsch's and Raimund Titsch's acts of rescue? What aspirations for saving others appear in this account?

- Describe Julius Madritsch and Raimund Titsch: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did Julius Madritsch and Raimund Titsch face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps were they called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 4

Group 4[Download Handout for students]

Andree Geulen Herscovici (Belgium)

"I was a young woman. No different than others. Not better, not worse. Life left me distant from the upheaval going on around me," said the teacher Andree Geulen Herscovici years after the Holocaust. What motivated a 20-year-old woman to change the course of her life, which had been tranquil to that point, and join the ranks of an underground whose aim was to fight the Germans in order to save Jewish children? From the first time Andree saw a child humiliated by racial laws, she began to act and was incapable of stopping. She dedicated her life to this cause, and when she would go to bed each evening she would say to herself before falling asleep: "We saved five children, five more children were not exiled."

Like most Belgians, Andree, a young teacher at the local school, did not pay much attention to the anti-Jewish measures and persecution taking place in her country. One day, one of her students showed up wearing a Jewish star on his clothing. This sight shook her to the core. She immediately instructed all her students to wear aprons to school, to cover the humiliating sign forced on the Jews. At least within the walls of the school, the Jewish student could be protected from humiliation. This was a life lesson for the other students, and everyone obeyed her instruction.

Acts like these quickly became insufficient for young Andree. She was fully committed to "opposing the never-ending outrage of racism," as she described it. She met Ida Sterno, a Jewish member of the clandestine organization Comité de Défence des Juifs – Jewish Defense Committee – who brought her into its ranks. Ida needed a non-Jewish partner who would help her accompany Jewish children to their hiding places, and Andree needed a framework in which she could act and assist. Andree was given a code name – Claude Fournier – and was told leave her parents’ home and move to the boarding school where she was teaching. The Gaty de Gamont School was deeply involved in hiding Jewish children. At the initiative of the headmistress Odelle Oubart, twelve Jewish students were hidden at the school at a time when there were not many safe places for Jewish children.

In May 1943, the Germans raided the school in the middle of the night. It was during Pentecost – all non-Jewish students were spending the holiday with their families at home, while the Jewish children who had nowhere to go stayed behind at school. The Jewish children were dragged out of their beds and interrogated about their identity. The children were immediately arrested and the teachers also taken for interrogation. When the German interrogator looked Andree in the eye and scornfully asked if she wasn't ashamed to teach Jews, she responded without hesitating: "Aren't you ashamed to make war on Jewish children?"

Andree managed to evade arrest, but the night took its toll. The headmistress and her husband were arrested and deported to concentration camps in Germany, where both died. They were later recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations.

After that traumatic evening, Andree went from house to house among her Jewish students, telling them what had happened and warning them not to return to school. She knew the Germans were liable to return. Her involvement with rescue deepened further, and she now embarked on a clandestine existence. She rented an apartment under a false name, which she shared with Ida Sterno. Contact with the rescue organizations was maintained through secret post office boxes, one of which was located in an antique shop. From there information and orders were passed, and Andree's activities continued undiminished. For over two years, she visited Jewish homes and extended her hand to the children, without being able to tell their parents where she was taking them. The children would hold her hand in theirs, and with their other hand clutch a suitcase of treasures that their mothers had tearfully packed. Andree often sang to the children, and today believes that the children remembered this pleasantness amidst the fear and uncertainty associated with those days. Sometimes she would take children as young as two or three years old. She would drill into her memory the false names of the hidden children and their addresses – information with life and death consequences. In secret, she prepared lists with the real names of hundreds of hidden children, some of whom never saw their parents again. In doing so, she preserved the children's Jewish and family identity, which depended entirely on her ability to recall, as young children forget these details easily. Parents begged to know where she was taking their children, but she could not reveal her hiding places. She learned that if she did, the parents would not be able to resist visiting the areas where their children were in hiding, thus putting them all at risk. While Andree herself visited these houses, it often happened that a raid would take place: blocked streets, soldiers everywhere, and trucks waiting to take away the innocents caught by the Gestapo. In these circumstances, she managed to save a few children. She would cross over the checkpoints, with one child in a stroller and others holding her hand, looking like a young mother of several children. The soldiers were embarrassed to confront her and in this way, she saved the hidden children, though sadly not their parents. When she managed to save a child, she felt a great sense of satisfaction and an uplifting of her spirits. Years later, she compared the feeling to raising children of her own.

One time, a passerby stopped Andree as she was walking with a Jewish child, and innocently asked the child's name. The child looked at her and whispered, "Should I give my real name or my fake name?" It was a terrifying moment. Andree gestured to the child to be silent, and not say anything.

In May 1944, Ida Sterno was arrested and sent to the Mechlin transit camp, from which Jews were sent to Auschwitz. Although Andree 's life was in great danger, she visited Ida in the camp, granting her a few extra moments of humanity and friendship.

The young teacher acted to save Jews until the last day of the war, and was a member of a network of underground groups. Most of the children did not know that their rescue was part of these groups, nor did they know that Madame Andree Guelen was responsible for their rescue. Henri Novak, one of the rescued children, later related: "About a decade ago, while visiting with my wife in Brussels, my cousin invited me to Shabbat dinner at a Jewish club. The hall was full and someone asked me if I knew Madame Guelen. I answered that I had never heard the name. 'Come let me introduce you," he said. We went to the table, and sitting there was a woman I did not know. My friend said to her "Madame Guelen, I want to introduce to you my friend from Israel. The woman raised her head and asked my name. 'My name is Henri Novak,' I said. She gave me a long look and said '1059'. I was stunned. I said her 'Excuse me, to what are you referring?' She replied 'That was your code number during the war. We took care of you after your parents were no longer around.' From that moment, everyone became clear to me. I learned things that I hadn't known for a long time."

Many years after the Holocaust, Andree Guelen visited Jerusalem to attend a conference of children hidden in Belgium, and there she proclaimed in front of all: "I loved you all so much then, and I still love you so much today."

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Andree Guelen's acts of rescue?

- Describe Andree Guelen: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did Andree Guelen face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps was she called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 5

Group 5[Download Handout for students]

Jan and Antonina Zabinski (Poland)

What motivates a person to risk his life and the lives of his wife and children for strangers whom he mostly has never met? What brings him or her to become caught up in a tangled web of illegal activities, for which the penalty is death? Dr. Jan Zabinski, with his sparkling blue eyes behind his spectacles, answered these questions without hesitation: "I endangered myself and assisted them not because they were Jewish, but because they were persecuted. If the Persecuted had been Germans, I would have behaved the same way. We are talking about innocent people upon whom death had been decreed. It was shocking. I fulfilled a simple human obligation."

When war broke out and the Germans bombed Warsaw, Dr. Jan Zabinski was the head of the Warsaw Zoo. This zoo was one-of-a-kind, sprawling over a vast area. His wife, Antonina, ensured that the zoo grounds were green and beautiful. The heavy bombings of the city destroyed a significant portion of the zoo, and some animals were killed. Two months after the German occupation, the head of the Berlin Zoo, Lutz Heck, visited Warsaw. He knew the Zabinskis from before the war and was friendly with them. This time he came with an order – to transfer all the valuable animals to Germany. Heck told Antonina that this was only a temporary arrangement. Antonina didn't believe a word.

With the cages now empty, the couple needed a pretext to continue running the zoo. Zabinski convinced Heck to convert the zoo into a pig farm, providing food for German soldiers stationed in the Warsaw area. That same year, the Jewish ghetto began to form in the city. After the war, Zabinski testified that he when he asked Heck for the permit, he saw an opportunity to smuggle food to his ghetto friends. A few days later, Heck and his men returned to relocate the zoo's animals to various zoos within Germany. The animals that remained were hunted down and killed in cold blood.

The Germans formally tasked Zabinski to be the general supervisor of Warsaw's public parks. Within the Warsaw ghetto there were no parks, but Zabinski visited there anyway, and in this way a food-smuggling network began to form, in which Zabinski played a key part. One day, a member of the Polish underground phoned Zabinski and warned him to "expect guests." This was just the beginning. Slowly the Zabinskis' home filled with many guests: Jews and non-Jews seeking shelter. Many needed temporary shelter until they could procure forged documents. Among those who knocked on their door were Jews who looked "Polish," and were presented to the Zabinskis' maid as family members. Dark-complexioned Jews were transferred to the basement and to empty cages.

The house continued to burst with life. Guests were invited for dinners and musical evenings, as Antonina believed that by creating a general bustle it would be easier to hide people. Not everyone could leave the ghetto on their own, so Zabinski started to enter the ghetto to help smuggle people out, one person at a time. One day, a guard stopped him and asked the person he was smuggling out to identify himself. Zabinski replied coolly, feigning anger at the question, but this did not help. Ultimately, using a forged document from the Parks Authority, he was able to bring the Jew with him. A different time he smuggled out the widow of a friend, a woman named Lunia whose husband, an entomologist named Shimon Tannenbaum, had died in the ghetto. With great effort, they managed to leave the ghetto, but even after leaving, they saw two German soldiers in front of them. Lunia panicked and wanted to start running. Zabinski held her hand, picked up a cigarette butt from the ground, lit it, and, linking arms with her, calmly walked her past them.

Zabinski's name became known amongst the Polish underground, which created a Jewish rescue organization called Zegota. They continued sending Zabinski refugees, who stayed in the cages. In the evenings, Jan and Antonina's son Richard would bring the refugees food, after his father told him: "It's time to feed the peacocks." Among the refugees was the Levy family, who had come to the Zabinskis one evening seeking help. Mr. Levy, a lawyer, along with his wife and daughters, lived in the zoo for two years.

One day in December 1942, there was a knock on the door. Richard rushed to open it. There stood Regina Kenigswein with her two children, aged five and three. Kenigswein's father Sobol had supplied the zoo with fruit before the war. Antonina saw Kenigswein and her eyes filled with tears. She immediately let them into the house. Initially, they stayed in the lions' cage. Zabinski then smuggled Regina's husband Shmuel out of the ghetto. Regina later recalled, "In those days the zoo was like Noah's Ark – full of people in great flood."

"In that period," Jan Zabinski later described, "I was involved in all sorts of various activities, and the Germans had many reasons to hang me. Among other things, I lectured at illegally-run Polish universities, I was active in the Polish underground, and my zoo had an arms cache – so hiding Jews did not raise or reduce my level of danger… the true hero was my wife. The Jews were in her house all the time and she took care of their well-being and their needs, without complaint and without tiring, despite the constant fear we always felt."

In the summer of 1944, Poles rebelled in the city. Zabinski was injured in the battles, and later was taken captive by the Germans. Antonina was left alone with a four-month-old daughter and her young son, and on top of that agreed to take charge of the two Jewish daughters of the Levy family. Together they covered 120 kilometers on foot, Antonina with four small children. By the time she reached the town of Lubich, she could no longer feed the children. Miraculously, her situation became known to the Jewish committee that still existed in Warsaw. Through one of the committee's operatives, they managed to secretly deliver money to her.

In the years following the war, Jan Zabinski continued to run the Warsaw Zoo. Even after retiring, he carried on working with animals – preferring to speak about his love for them, rather than be asked about his all-encompassing love for humankind.

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Jan and Antonina Zabinski's acts of rescue?

- Describe the rescuers: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did they face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps were Jan and Antonina Zabinski called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 6

Group 6[Download Handout for students]

Dr. Ella Reiner-Lingens and her husband Kurt (Austria)

Ella and Kurt Reiner-Lingens were both young doctors in Vienna when the Nazis annexed Austria to the Third Reich. By this stage, Kurt had a long history of opposing the German government, a product of his upbringing as a minority Catholic among Protestants in his native Germany. The Catholic Church was known for its opposition to Nazism, and therefore its members were persecuted. The situation worsened to the point that Kurt, as a result of his student anti-fascist activities, was forced to move to Austria to complete his medical studies.

Ella was a native Viennese, an exceptionally talented woman who completed her doctorate in law and then moved on to medical training. With the annexation of Austria, she began to assist Jews. During the Kristallnacht pogrom, she hid ten Jews in her room. Later she agreed to hide a young Jewish woman named Erica Feldan. When Erica became ill and required surgery, Ella used her maid's identification papers to get the Jewish fugitive the care she needed at a time when Austrian Jews were outside the law and certainly ineligible to undergo surgery at a hospital.

Ella and Kurt's house was open to Jewish friends and acquaintances. Some of the Jews who reached their home left valuables with them so they would not be stolen. The Lingens helped in many other ways, all the while endangering their lives and that of their young son. They escorted Jews to the border in attempts to help them flee, and took care of their valuables in their absence.

The Lingens' fate was sealed by informants. On 13 October 1942, they were arrested by the Gestapo. The Germans sent Kurt to an army unit whose members were sent to the Russian front as a punishment for various crimes. There, Kurt was mortally wounded. Ella was orderd to be deported to Auschwitz, and she was forced to part from her young son. In the camp, she worked as a doctor for camp prisoners – and was thus able to save several Jews from death in the gas chambers. Even when her term of imprisonment was nearly complete, she took a fateful decision to stay on to help others. Toward the end of the war, she was sent on a death march to Dachau, in Germany.

Ella managed to survive the Nazi horror, and to stand proud both as a mother to her young son and as a member of the human race.

From the testimony of Ella Reiner-Lingens

"Most of the time, we could only watch helplessly as selections were performed. But one time, I was able to intervene. A few days before, I had been called to the political department… the patient was a woman named Lyman from Frankfurt. From the end of August 1943 until February 1944, selections were made every four weeks, not only from the sick wards but also throughout the camp. Some 500-1000 women were selected each time and I was certain that Miss Lyman would be among the victims. She was very depressed, shaking with fear and despair and clutching my hand tightly. 'Help me,' she begged again and again…

"The camp doctor had told me not long before that I needed to be very careful not to make mistakes, as my release was expected within a few weeks. As an Aryan German, my intervention on behalf of this woman would anger the Waffen SS and jeopardize my release. Only someone who had been in a concentration camp without knowing how long their imprisonment would last can understand the significance of this shard of hope for freedom. My son was only three when we separated. Only a parent of children can understand the depth of longing of a mother for her son. Alone and in pain, I paced back and forth along the path of the camp in the twilight of that winter day. Grey buildings, watchtowers and electrified fences stretched across the horizon – an image of ugliness and despair. I was about to be released from this places and its horrible memories, and now I was being asked to risk it all and make myself unpopular for the sake of Miss Lyman, who was basically a stranger to me.

"There wasn't much time, and I had to take a decision. In my mind's eye I saw my little boy and heard his sweet voice as we parted, wrapping his small arms around me and begging 'Mommy, please don't leave me.' And then I saw the eyes of this young woman who looked at me pleadingly as she said, 'I'm so happy to speak with a German.' There was a fierce struggle within me between wanting to go free and the mercy I felt toward this woman. My sense of obligation to save lives, as both a doctor and a human, conflicted with my obligation as a mother to survive for her son's sake, as each day in the camp increased the risk of death.

"No one could say the solution was clear or obvious. I was torn and couldn't reach a decision.

"Then, I had an insight. I had the privilege of claiming that my life and the life of my son was more important than the life of a stranger. But that wasn't what I was facing. If I failed, that is, allowed the murder of someone whom I perhaps could have saved, only because I myself was in danger, I would have made the same mistake as the German people… the people who ordered and carried out these horrible crimes were not many, but countless bystanders allowed them to carry out their plans because they did not have the courage to stop them. They claimed 'There was nothing we could have done,' even when they could have done something. If I turned my back, because I was afraid of staying longer in the camp, I would be no different than the all the other Germans who were free and who watched passively out of fear that they would be imprisoned and sent to a concentration camp. In this case, the SS would have successfully 'educated' me, as the Gestapo agents who sent me to the camp liked to say. The significance of this was – everything I sacrificed would have been in vain, and I might as well have stayed home. The feeling that welled up in me was neither mercy nor obligation, rather, a hatred for the regime that wanted to depress me and steal my honor. In my heart, I said to my child: 'Son, you may have to wait a bit longer for your mother, but when she returns to you, she will be able to look you in the eye and you won't have to be embarrassed that your mother tongue is German.'

"I turned and walked toward the political department of the women's camp…"

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Ella and Kurt Reiner-Lingens' acts of rescue?

- Describe the rescuers: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did they face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps were Ella and Kurt Reiner-Lingens called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 7

Group 7[Download Handout for students]

Maria Olt (Hungary)

"I could never have forgiven myself if I had acted differently in those horrible days. They were days of fear and dread, but because there was no time to ponder what would happen if we were caught, we ceaselessly continued our rescue activities." How did Maria Olt, who in 1944 was just 22 years old, become utterly intertwined with several Jewish families, to the extent that she was willing to risk her own life and the lives of her family for their sakes?

In the spring of 1944, the German occupation of Hungary had only just begun, but already Jews were persecuted. In March, Dr. Laszlo Kuti, a Jewish gynecologist who worked at a maternity hospital in Budapest, and his wife Miriam Kuti-Nevo gave birth to a daughter. Great fear and uncertainty accompanied the outbreak of war. Miriam later recalled, "The atmosphere at the hospital and throughout the city was difficult. We were despondent. Some of the hospital staff committed suicide." In April, Jews were ordered to sew the yellow star on their garments, the familiar, humiliating sign of being placed apart from general society."

During this time, Maria Olt came to be treated by Dr. Kuti. Seeing the doctor wearing a yellow star shocked Maria greatly. The doctor saw her open concern and told her about his sense of uncertainty and fear of what would become of him, his wife and newborn daughter, Anna. A man in great distress stood before Maria. She got up and declared, "I want to save the baby."

That same day Maria came home to her village holding their baby in her arms. Her husband immediately expressed his concerns. Hiding a Jewish child? Now? What sort of an idea was that? This could endanger the entire family. And for who, strangers? But Maria did not respond to his outbursts. She was a pious Catholic, and as a believer she felt obligated to show kindness to the oppressed. After some time, her husband left her and moved to a different city. Her father Jozef Lang, on the other hand, saw what his daughter had done and decided to help her and other Jews in need. A few days later, Maria returned to the city. This time it was to take Miriam, the baby's mother. She brought her back to the village and introduced her to all as a Gypsy who had given birth to a daughter out of wedlock and needed to hide to avoid revenge. The following week she brought Dr. Laszlo Kuti back to her village. He hid with Maria's father in the small cellar of a vineyard that Jozef owned.

Now Maria Olt was responsible for three people, including a baby. The danger was great. The general atmosphere in the village was one of anti-Jewish sentiment, and certainly of opposition to hiding Jews. Each day contained the fear of being discovered, informed upon or turned in. Maria managed to transfer little Anna to a family living in a small village near the Czech border. Maria obtained forged documents for Anna, and she was passed off as a Christian child, which protected her life and the lives of the family members hiding her.

One day, one of their greatest fears became a reality. The village midwife recognized Miriam. She had studied at the maternity hospital in Budapest and Miriam's face was familiar to her from there. The midwife quickly realized that she was the Jewish wife of Dr. Kuti, rather than a Gypsy, as she had been introduced. She immediately requested to denounce Miriam to the village police. Maria was stunned. Not only was Miriam's life in danger, but also that of her husband, her father and herself. Maria immediately decided to smuggle Miriam to a different village, where she could stay with relatives, far from those who wanted to turn her in.

But in this other village, the atmosphere toward Jews was hostile as well. One evening, she heard people gleefully describing how the farmers had ripped apart a Jewish storeowner limb from limb. Maria and Miriam continued their wanderings, with no documents – even Maria no longer had documents, as she had given them to an acquaintance of the Kutis, a Jewish woman who had needed a certificate declaring her to be Christian into order to escape. The two went from place to place, looking for food and a place to rest. Their fates were intertwined.

One day, in the course of their difficult journey, they came across a train transporting Jews to Poland – to Auschwitz. The train stopped for a moment not far from where they were. Miriam felt an urge to join the passengers and end her suffering once and for all. Maria caught her hand and said: "If you go on that train, I will follow." Years later, Miriam remembered: "It was her bravery that kept me from taking that step and instilled in me the strength to continue hiding until the end of the war." The days passed, and Maria miraculously managed to borrow enough money to rent Miriam a room in the village. Not long afterward, Maria arrived at the village in her father's cart. Underneath a pile of hay, Dr. Laszlo Kuti, Miriam's husband, was hiding. The two reunited and together waited for the fury to subside.

Miriam continued helping other Jews. Each time a scared person came to her, Miriam initiated a rescue attempt. Some of the Jews hiding in one of the villages received weekly visits from Maria, who looked after their needs as best she could. Her rescue activities continued until Budapest was liberated in 1945. After the war, the people Maria saved scattered around the world. Miriam, who immigrated to Israel in the 1950s, maintained regular contact with the woman who had rescued her and her son. Thirty-four years after promising to meet one another in Jerusalem and then going their separate ways, the two managed to fulfill this wish. In a ceremony held at Yad Vashem, Maria said: "I felt a need to help the persecuted. An inner voice spoke to me in those days and guided my behavior without thinking about the dangers around me. I would never have forgiven myself had I acted differently."

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Maria Olt's acts of rescue?

- Describe Maria Olt: age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did Maria face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps was Maria called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If the latter, what were they?

Group 8

Group 8[Download Handout for students]

Roddie Edmonds

Master Sergeant Roddie Edmonds (b. 1919) of Knoxville, Tennessee, served in the US Army during World War II. He participated in the landing of the American forces in Europe and was taken prisoner by the Germans. Together with other American POWs, including Jews, he was taken to Stalag IX A, a camp near Ziegenhain, Germany. In line with their anti-Jewish policy, the Germans singled out Jewish POWs, and many of them on the Eastern Front were sent to extermination camps or killed. In some cases in the west Jewish POWs were also separated from the others. Sometime in January 1945 the Germans announced that all Jewish POWs in Stalag IX A were to report the following morning. Master Sergeant Edmonds, who was in charge of the prisoners, ordered all POWs—Jews and non-Jews alike—to stand together. When the German officer in charge saw that all the camp’s inmates were standing in front of their barracks, he turned to Edmonds and said, “They cannot all be Jews.” To this Edmonds replied, “We are all Jews.” The German took out his pistol and threatened Edmonds, but the Master Sergeant did not waver and retorted, “According to the Geneva Convention, we have to give only our name, rank, and serial number. If you shoot me, you will have to shoot all of us, and after the war you will be tried for war crimes.” The German gave up, turned around, and left the scene.

Paul Stern, one of the Jewish POWs saved by Edmonds, has been taken prisoner on December 17, 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge (a German offensive campaign on the Western Front, December 16, 1944–January 25, 1945). He described how the prisoners were forced to march for four days in the bitter cold to a railway station. Some POWs died on the way. At the station they were loaded into boxcars and driven for several days, without food, to a camp near Bad Orb, Stalag IX B, where the Jewish POWs were segregated into special barracks, with lice-infested mattresses and starvation food rations. Stern and the other Jewish noncommissioned officers were fortunate and were taken to the nearby camp of Ziegenhain, while the other lower ranking Jewish POWs were sent to slave labor camps. It was in this second camp, Stalag IX A, where, thanks to Edmonds’s courage, Stern and the other Jewish POWs were saved from the second attempt to single out the Jewish POWs.

Stern told Yad Vashem that though he had learned German in college he did not reveal this to the Germans; he was able to listen to what the Germans were saying without them knowing that he understood them. Stern stood near Edmonds during the exchange with the German officer. The exchange between the German and Edmonds was in English. “Although seventy years have passed,” said Stern, “I can still hear the words he said to the German camp commander.”

Another witness to the exchange was Lester Tanner, who had also been captured in the Battle of the Bulge. Tanner had been inducted into military service in March 1943 and had trained in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. Master Sergeant Edmonds was the highest ranking noncommissioned officer in the 422nd Infantry Regiment, and Tanner remembered him well from his training period. “He did not throw his rank around. You knew he knew his stuff, and he got across to you without being arrogant or inconsiderate. I admired him for his command. . . . We were in combat on the front lines for only a short period, but it was clear that Roddie Edmonds was a man of great courage who led his men with the same capacity we had come to know of in the States.” Tanner told Yad Vashem that at the time, they were well aware that the Germans were murdering the Jews. They therefore understood that the order to separate the Jews from the other POWs meant that the Jews were in great danger. “I would estimate that there were more than one thousand Americans standing in wide formation in front of the barracks, with Master Sergeant Roddie Edmonds standing in front of the formation with several senior noncoms beside him, of which I was one. . . . There was no question in my mind or that of M/Sgt Edmonds that the Germans were removing the Jewish prisoners from the general prisoner population at great risk to their survival. The US Army’s standing command to its ranking officers in POW camps is that you resist the enemy and care for the safety of your men to the extent possible. M/Sgt Edmonds, at the risk of his immediate death, defied the Germans with the unexpected consequences that the Jewish prisoners were saved.”

Chris Edmonds, Roddie's son, told Yad Vashem that his father had kept a diary in the camp, where he also had other POWs write down their names and addresses. Food rations were very small, and the POWs were hungry, so Edmonds with some other friends planned to open a restaurant after the end of the war. Edmonds who was artistically talented, made drawings of the restaurant and sketched its logo. These plans were abandoned after his return home.

Discussion Questions:

- What motivated Roddie Edmonds act?

- Describe the rescuers: Age, gender, political and religious outlook, etc.

- What difficulties and dangers did he face?

- Was the rescue a result of a one-time decision or perhaps was he called upon to take responsibility for rescuing at several points? If at several points, what where they?

Classroom discussion

Classroom discussionAsk the students to present the story and the character of the rescuer/s. Then discuss the following questions:

- What were the challenges common to all those who attempted to rescue Jews?

- In light of the great variance between the types of Righteous Among the Nations, what did they nonetheless have in common?

Examine the following quotes and discuss them in light of the above questions

Dr. Giovanni Pesante and his wife Angelica, from Trieste, Italy, hid Hemda, their daughter’s Jewish friend, for over a year. When Hemda suggested that she leave so as not to jeopardize them, Dr. Pesante said to her:

”I beg you to stay with us for my sake, not yours. If you leave I will forever be ashamed to be part of the human race.”

Chiune Sempo Sugihara served as vice consul for Japan in Lithuania. During the Second World War, Sugihara helped some six thousand Jews flee Europe by issuing transit visas to them so that they could travel through Japanese territory, risking his job and his family's lives. After the war he explained:

"You want to know about my motives, don't you? Well, it is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees the refugees face-to-face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them. Among the refugees there were the elderly and women. They were so desperate that they went as far as to kiss my shoes. Yes, I actually witnessed such scenes with my own eyes… People in Tokyo were not united [on a refugee policy]. I felt it kind of foolish to deal with them. So I made up my mind not to wait for their reply. I knew that somebody would surely complain in the future, but I myself thought this would be the right thing to do. There is nothing wrong in saving many people's lives. If anybody sees anything wrong in the action, it is because something 'not pure' exists in their state of mind. The spirit of humanity, philanthropy…neighborly friendship…With this spirit I ventured to do what I did, confronting this most difficult situation – and for this reason I went ahead with redoubled courage."

Pastor André Trocmé was the spiritual leader of the Protestant congregation in the village of Le Chambon sur Lignon in the district of Haute-Loire in Southeastern France. When the deportations began in France in 1942, Trocmé urged his congregation to give shelter to any Jew who might ask for it. The village and its outlying areas were quickly filled with hundreds of Jews. Some of them found permanent shelter in the hilly region of Le Chambon, and others were given temporary asylum until they were able to escape across the border, mostly to Switzerland.

The authorities demanded that the pastor cease his activities. His response was clear-cut:

"These people came here for help and for shelter. I am their shepherd. A shepherd does not forsake his flock... I do not know what a Jew is. I know only human beings."

Adolf Althoff's family had owned the famous Althoff circus since the 17th century. The Adolf Althoff circus, which consisted of approximately 90 artists and their families, toured all over Europe, and continued its regular activity throughout the war years, traveling from one place to another. During the Holocaust he agreed to employ Irene, a young Jewish woman, in his circus, under an assumed name. He later explained:

"I couldn't simply permit them to fall into the hands of the murderers. This would have made me a murderer."

Poem by Hannah Senesh

In the fires of war, in the flame, in the flare,

In the eye-blinding, searing glare

My little lantern I carry high

To search, to search for true Man.

In the glare, the light of my lantern burns dim,

In the fire-glow my eye cannot see;

How to look, to see, to discover, to know

When he stands there facing me?

Set a sign, O Lord, set a sign on his brow

That in heat, fire and burning I may

Know the pure, the eternal spark

Of what I seek: true Man.

Hannah Senesh: Her Life and Diary, the First Complete Edition, 2013

Emanuel Levinas

Jewish philosophy sees the face of the other as one of the main points of interface between man and his companion. The connection between people, beyond language, culture and other cues to assist interpersonal communication, is based on the innate ability to see, to gaze, to look into the face of the other and understand, without words, the internal state of the person standing before him. If we see a man laughing and his eyes are laughing, we conclude that all is well with him, and alternatively a man who is crying and his face is sad leads us to conclude his situation is bad. In addition to this, we are given many universal cues to human emotion: Fear seen on the face, dread in one's eyes, excitement, satisfaction, uncertainty, delight and many other emotions that speak to us from the face of the other. The responsibility bestowed to us as viewers of these emotions is clear: a fitting response. Fitting would be a response that directly relates to the other's emotional state and does not ignore it or claim it is other than it appears. Few were those who saw Jews' faces during the Shoah. Many no longer saw the human gaze of the Jews or made excuses for the sake of their conscience about why they were unable to help the Jews standing before them. Very few were spurred by the Jews' bleak countenance to take a moral stand.

Read the following passages about Levinas's approach and discuss the questions that follow.

As [Emanuel] Levinas has taught us, the internal world of man is expressed through the face… The expression "face to face" describes the conversation between one and the other… the most tragic facial expression is tears. When I see the facial expression of the other, I am compelled to respond to what is before me.

Shalom Rosenburg, The Other – Between Man, Himself and his Fellow, Editors: Chaim Deutsch and Menahem Ben Sasson, Yediot Aharonot, Chemed Books, Tel Aviv 2001, pg. 59-60.

However, Levinas goes further than that. He points out is not just a matter of recognizing the other, but also it establishes the relationship between myself and the other. The other creates a responsibility for me to care for him, to feel for him without expecting any reciprocation. The call for connection with the other is expressed through his face.

- What does the expression "face to face" mean according to this passage?

- How does the face reflect a person's internal-emotional state?

- Why is it that "when I see the facial expression of the other, I must respond to what is before me"? Do you agree with this assertion?

- What responsibility, in your opinion, does the other create in me when he looks at me? What is the significance of my not responding to his facial expression?

- According to Rosenburg, how can the acts of Righteous Among the Nations be explained?

Examine with the students the following Hassidic saying, and discuss how this saying describes the world of Righteous Among the Nations during the Holocaust:

"Three things are pleasant for a man:

To be bent but straight

To cry out silently

And to be alone in the marketplace square"

Hassidic Sayings

"To be bent but straight": The Righteous Among the Nations may be perceived as people who could have surrendered to the general mood and the German threat but were able to live according to their principles and maintain a moral stance: This is an expression of standing straight while being bent by outside pressure. For many of the Righteous Among the Nations, being bent was also expressed by their behavior after the war, when they chose to retain their privacy and did not feel that their exceptional deeds made them worthy of publicity.

"To cry out silently": The actions of the Righteous Among the Nations are a loud cry against the evil, cruelty and indifference that surrounded them, but because of the situation their cry needed to be made silently, without anyone knowing of it. Their cry takes on added significance in light of the silence around them.

"To be alone in the marketplace square": The marketplace square symbolizes the crowded multitudes. The same person who feels alone in the square takes upon him or herself a historic role, not as one who stands out or attracts a following but rather as one who preserves for the future his moral values and bequeaths to the "post-destruction" society a basis for a new beginning. He or she does all this without disconnecting from the surroundings, or doing anything that might raise suspicions of others.

There is a commonality to all the rescuers of Jews, although there was often a difference in the places they operated, their motives, and their level of familiarity with the Jews they saved. There is great educational value in finding the common threads from among the different rescuers. Unlike those around them, the rescuers saw the Jews as people, and recognized their own moral obligation toward them. The summary activity will focus on the moral imperative that these people felt when they looked at the faces of Jews. This sense was translated into action, sometimes instinctively, and only over time were these acts recognized as stemming from an ethical imperative. These acts expressed then, and express for us today, an unmediated connection, a moral imperative between human beings.

Rabbi Ephraim Oshry discusses in his book a question he was asked after the war:

…In 1945, shortly after our liberation, Reb Moshe Segal came to me with the following question: He had been saved by a gentile woman who, at enormous risk to herself, had hidden him in her basement together with ten other Jews, providing them all with food and shelter until the liberation. After the war, when those Jews wanted to repay her in some way for her great compassion, they discovered to their deep sorrow that she had died right after the liberation. The idea took root in their minds to say Kaddish for her, and Reb Moshe Segal was chosen for the task. His question was whether it is permissible to say Kaddish for a gentile?

…The work Sefer Chasidim teaches that it is permissible to ask of G-d to accept favorably the request of a non-Jew who has done favors for Jews. And saving his life is the greatest favor that one can do for a Jew. Not only is it permissible to say Kaddish with her in mind, it is a mitzvah to do so. May He Who grants bounty to the Jewish people grant bounty to all the generous non-Jews who endangered themselves to save Jews.

Rabbi Ephraim Oshry - Responsa from the Holocaust, NY, NY, pg. 164-165

- What is the significance of "Kaddish"?

- For whom is "Kaddish" said?

- Why does Rabbi Oshry emphasize that it is a mitzvah to say "Kaddish" for the gentile woman?

The obligation of the individual to save one whose life is in danger is clear but as a society we should consider: If so few people rescued Jewish people during the Holocaust.

- Why is it important to tell the stories of Righteous Among the Nations?

- What is the significance today of the fact that there were Righteous Among the Nations during the Holocaust?

Recognizing Righteous Among the Nations has value not just in terms of showing gratitude, though that is an important value, but also as an educational tool. Professor Philip Zimbardo asserts that due to the powerful events of World War II and the atrocities of the Holocaust, research focuses on the question of how normative people became capable of extreme violence and evil. But if research reached the conclusion that normative people can be influenced such that in certain conditions they would act in a way that they themselves under different conditions would define as unacceptable – we therefore need to see how to cause people not to cross the line between good and evil and rather stick to good, even in situations of obeying authority and other environmental pressures. Against the so-called "banality of evil," he suggests countering with the "banality of heroism" – heroism not of superheroes or of those who take actions outside the norm, but those who cling to their values despite their circumstances. He calls for creating a situation in which children are encouraged to imagine heroism. People need to think of themselves as "heroes in waiting," and focus their lives on distancing themselves from evil. In his view, children should be educated that it is likely that they will face a momentous decision and will be asked to choose from among three options: The first option is to become complicit and engage in acts of evil and cruelty; the second option is to be indifferent and, in practice, guilty of inaction; and the third option is to stand on one's principles and cling to good, a choice which turns the protagonist into a hero.

The significant point here is whether we are ready to choose the path that praises the simple heroes, who are waiting for the right situation to put their imagined heroics into action. This chance is likely to come up maybe once in a lifetime, and whoever misses the opportunity will live with the knowledge that "I could have been a hero but I let the moment pass."

In the post-Holocaust generation, the responsibility of humanity is not merely to "avoid evil," but also requires education to "do good." Doing good, according to Zimbardo, requires applying the idea of "First think, then act." If we think and imagine ourselves as clinging to good and to our values, when these values are tested we will be equipped with the power to withstand evil.

Historical Appendices

Historical AppendicesA Look at Various Countries in the Context of Rescue

Austria

Austria was historically the ethnic German component of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Following World War I, with the crumbling of the empire, Austria became a separate republic. In March 1938, Austria was annexed to Nazi Germany and became an integral part of it. Most Austrians were agreeable to or even enthusiastic about this "Anschluss" (annexation). Only a small minority maintained opposition to the new regime, organizing in underground movements that encompassed several schools of thought: socialists, communists, Catholics, and conservative patriots. Austrians was considered by Germans to be fully "Aryan" – from the perspective of ideology, race and culture, the Nazis saw them as full partners in the Nazi vision and the Nazi path. Key figures in the upper echelons of the Nazis were Austrian.

Austria quickly began to persecute its Jews, stripping of them their property and distancing them from society, economy and culture. A few days after the annexation, German Interior Minister Heinrich Himmler granted special authority to act outside the law in Austria for the sake of "preserving order and safety," and this became the basis for anti-Jewish activities in Germany as well. A Gestapo center was established in Vienna, and shortly afterwards other centers were created in Austria's major cities. Already in March 1938, Jewish community offices and Zionist institutions were closed in Vienna; and their directors were arrested and sent to the Dachau concentration camp. The Gestapo started a campaign of organized robbery of Jewish-owned homes, including confiscating property, artworks, carpets, furniture and other valuables, all of which was transferred to Berlin.