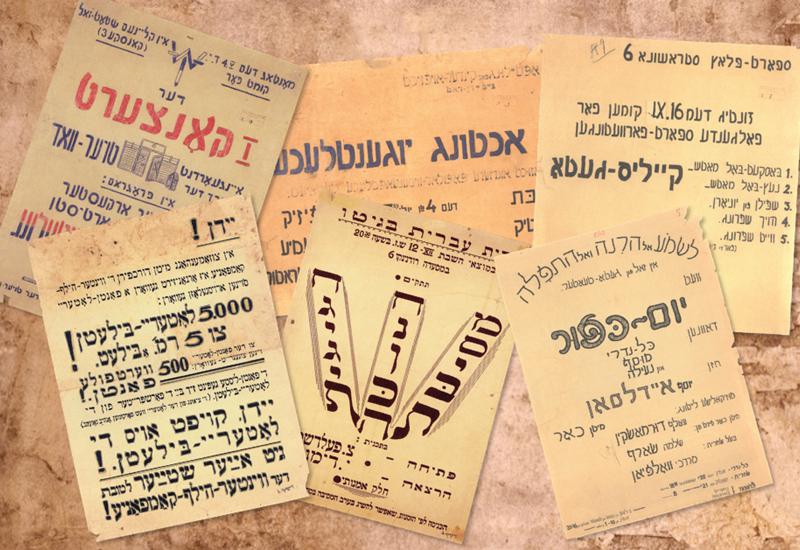

After Vilna's liberation in the summer of 1944, a group of local partisans who had spent the war in the forest returned to the ruins of the ghetto. In mounds of garbage and various hiding places, they found and extracted precious documentary evidence of life in the ghetto, including more than 200 posters inviting the public to participate in various events in the ghetto. For this unit, we have chosen to focus on eight of these posters in an attempt to learn how they reflect cultural life within the Vilna ghetto.

In central and western Poland, most ghettos were established prior to the start of the mass killings of Jews as an interim means of dealing with what they claimed to be the "Jewish Problem." In the East, however, ghettos such as the one in Vilna were created while the killing of Jews was underway. Consequently, from its first days, the Vilna ghetto existed in the looming shadow of death. This context is essential for analyzing the posters that were found, both in terms of their content and in their manner of design. The posters reveal the varied cultural life within the ghetto, and the attempts to raise the residents’ spirits by maintaining a fragment of the rich cultural life of Vilna’s prewar years – which was also a demonstration of defiance and resistance.

The posters are typically an invitation to participate in one type of event or another; however, from the posters themselves it is difficult to discern how the attempts to continue cultural life in the ghetto were received by the public and how the public felt about attending these events in the midst of chaotic circumstances. To present a fuller picture, the attached kit includes memoirs and testimonials from the ghetto, which shed light on the attitudes of the public toward these cultural activities. It is important to understand that the Jewish population of the ghetto was not of one mind regarding the appropriateness of cultural events in ghetto life. Arguments and public debate on this issue, as reflected in the firsthand sources from that period, demonstrate the varied efforts to maintain human dignity under impossible circumstances.

This unit focuses on the Vilna ghetto, which, like other ghettos established in the area of the Former Soviet Union, was created following the onset of mass killings. This reality made death a tangible presence from the ghetto’s first days of existence. The unit highlights ghetto cultural life in a world of rupture and chaos and in the shadow of death, and attempts to illuminate its significance during that time, as well as for us today.

Unit Structure:

- Introduction: Testimony about the life and atmosphere in the ghetto.

- Group activity: posters from the Vilna ghetto. You may also wish to hold a class discussion regarding a selection of the posters.

Summary: Discussion of the significance of Vilna ghetto cultural life using art and poetry.

Educational Unit

Educational Unit

The Walls Tell Stories: Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto

Introduction: Testimony about the life and atmosphere in the ghetto

Introduction: Testimony about the life and atmosphere in the ghettoDaily life in the Vilna ghetto was, to a large extent, an attempt to continue a routine, despite a new reality marked by the relentless murders and the difficult conditions of ghetto life.

Cultural and spiritual activities in the ghetto took place against a backdrop of destruction, with no knowledge of the fate of those deported from the ghetto. In addition, the uncertainty regarding the future, both of the individual and of the entire community, affected these activities. In light of this, it is important to present to students the mood within the ghetto and its significance before delving into the existence and nature of cultural activities.

Dina Levine Baitler was born in Vilna in 1934, the second daughter in a family of five. In 1940, when Vilna was under Soviet occupation, Dina's father was deported to Siberia, accused of being a "capitalist." In 1941, the Germans conquered Vilna, and soon after, during an aktion in the ghetto, Dina, her older brother and her grandmother were caught and taken to the killing pit in Ponary. There, on the edge of the pit, they were shot together with thousands of other Jews taken from the ghetto. Seven-year-old Dina, who was slightly wounded by a bullet in her leg, fell into the pit. "At night," she describes, "I heard a voice of a woman asking in Yiddish if anyone else was alive. There were wounded people who called out for help. The guards, who apparently were still there, heard them, came back, and started to shoot again." Towards morning, Dina pulled herself out of the pit and headed in the direction of the forest. She wandered through the forests and villages for the rest of the war, begging for food and shelter. At one point, she met a woman who helped her adopt the false identity of a Polish orphan, and with that identity she continued her wanderings until she came across Russian soldiers to whom she told her story.

The Vilna ghetto was established in September 1941, after the Jews had already been exposed to violence; men had been kidnapped to work details, and in a murderous aktion, thousands of Jews were sent to the Ponary forest to be murdered. In fact, the murder of Jews had been underway since July 1941, shortly after the Germans occupied Vilna.

In the first months after the ghetto’s establishments, aktionen continued. In January 1942, a period of relative stability began in the ghetto. During this period, of the 60,000 Jews living in Vilna on the eve of World War II, only some 20,000 remained in the ghetto. All those who remained had been exposed to extreme violence, horrors and grief; all had lost friends or family members.

Regarding the way in which these events affected the spirits of ghetto residents, Mark Dworzecki, a Jewish doctor who had been incarcerated in the ghetto, wrote in his memoirs:

"Who can fathom the state of mind and the mood of the ghetto man? How does he adjust to ghetto conditions? How does he respond to them?

"You need to fight for your life. You must always remain alert, as at any moment an unexpected danger can ambush you. You must control your mood, your nerves; foresee dangers and avoid them, escape them […] hope until the last moment, overcome and live under all conditions, in spite of the conditions. The ghetto is a temporary circumstance, after which will come freedom.

"These are the fundamental thoughts of everyone in the ghetto. Hold on – this is the aspiration, the motto of every person. In the most difficult times of the aktionen you must display self-control, and if you do not, you will be lost and are bound to lose the precious opportunity to save your own life. You must dress reasonably – so as not to forget that you are human. You can't be slovenly. If your soul is weighted down with concern – go to a concert, a play at the ghetto theater – you need to put aside the sadness, so that you'll be able to think, and sadness will not cloud your thoughts at a critical time.

"Like someone receiving medication, like those who receive a transfusion, this is how it was for those who periodically went to the satire plays at the theater, to laugh a little and dissipate the 'black bitterness," to force themselves into a lighter mood, and forget for several hours the melancholy and despair."

Meir (Mark) Dworzecki, The Jerusalem of Lithuania in Revolt and in the Holocaust (Tel Aviv: Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael , 1951).

Meir (Mark) Dworzecki: a Jewish doctor in the Vilna ghetto. During World War II, he served in the Polish Army and fell captive to the Germans. After escaping from a POW camp, he returned to Vilna. In addition to his work as a doctor, he was a member of the ghetto underground, but before he was able to escape to the forest and join the partisans, he was sent to a forced labor camp in Estonia. At this camp, he attempted to save sick prisoners who were liable to be murdered by masking their illnesses. After the war, he made aliya (immigrated to Eretz Israel), where he worked to commemorate the efforts of Jewish doctors to save lives during the Holocaust. As an established historian, he also endeavored to document the Nazis' medical war crimes. Dworzecki, who testified at the Eichmann trial, died in 1975.

- In his writings, Dworzecki relates to two different aspects of ghetto life – what are they?

- The question of survival in the ghetto became essential, but at the same time, Dworzecki emphasizes the need "not to forget that you are human." Discuss with students why Dworzecki stresses the importance of dress in the ghetto.

- What is the connection between the two main aspects of life in the ghetto?

Group activity about the posters from the Vilna ghetto

Group activity about the posters from the Vilna ghettoAfter Vilna's liberation in the summer of 1944, a group of Jewish partisans, who taken refuge in the forest during the war, returned to the ruins of the ghetto. In mounds of garbage and various hiding places, they found and extracted precious documentary evidence of life in the ghetto, including more than 200 posters. These posters are testimony to the cultural and spiritual life within the Vilna ghetto. The posters, alongside the voices of those who were there, reflect the contradictions that existed side by side within the ghetto: good and evil, despair and hope, self-sacrifice alongside a struggle to survive. This life, with all its complexities, took place in the shadow of the continuing slaughter of tens of thousands of Vilna ghetto Jews at the killing site in Ponary.

We recommend dividing the class into groups, with each group focusing on one or two of the posters. They can discuss issues raised by each poster, using source materials and the accompanying discussion questions.

The group activity about posters will focus on the following areas

Posters 1 and 2: The "Gatekeeper" Concert – an activity about ghetto theater and the controversy it caused – the question of whether it was appropriate to stage public cultural events at a time when thousands of people were being murdered in nearby Ponary.

In this context, another question can be raised: Was cultural activity actually able to make one forget the death-ridden reality of ghetto life, even for a short period?

Poster 3: Lectures for Youth – Educators and the education of youth in the ghetto played a special role within the atmosphere of rupture and destruction: to protect the emotional wellbeing of the young, despite the looming peril. In addition, training youth with skills they would need in the future was itself an expression of faith that survival was possible and that the war would eventually end. Discussion of this poster raises the duality of the existence of both good and evil in the ghetto.

Posters 4 and 5: Sporting Competitions – The creation of a sports field within the ghetto sparked various reactions. Some viewed it as a means of raising morale and an expression of clinging to life – despite the terrible surroundings. Others claimed that sporting activities was a distraction from the daily realities of potential destruction.

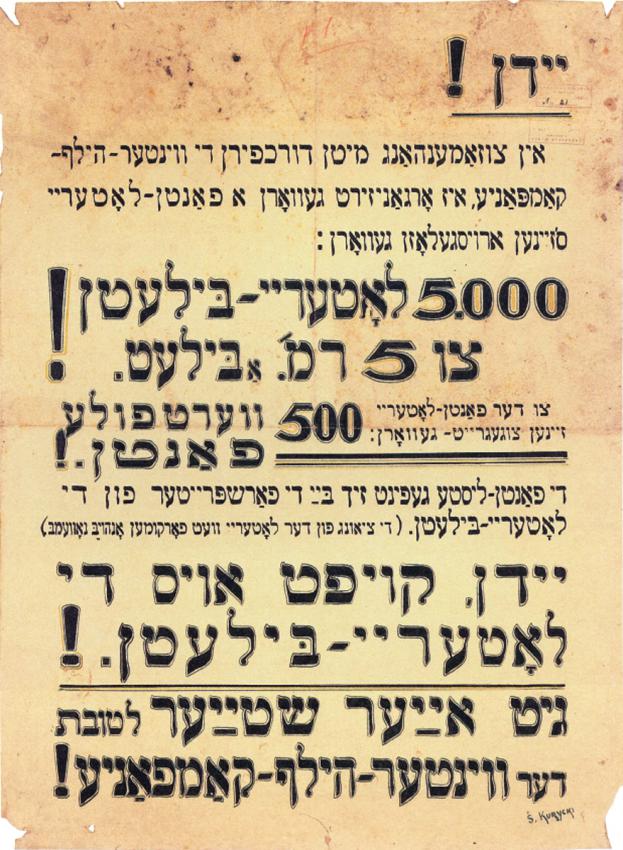

Poster 6: Lottery Drawing – The ghetto lottery was a social aid program and a financial investment in the future. Participating in this lottery occurred notwithstanding the daily uncertainty and in spite of the Ponary murders. This drawing testifies to a willingness of its participants to engage in their present and future. It is likely that the lottery's designated earnings that were earmarked for "Winter Assistance" (a social aid program that involved gathering and distributing clothes to the needy) was a weighty factor for those who chose to participate.

Poster 7: Chanukah Party; Posters 8 and 9: Yom Kippur Prayers and Prayer Day – A discussion of how much traditional Jewish holidays and prayers were maintained can be approached by comparing practices in the ghetto to practices in the period before the Holocaust. This raises the issue of the significance of maintaining Jewish tradition in the face of the unprecedented despair of ghetto life. Jewish holidays were celebrated by all social, religious and political groups in the ghetto, each in their own way and according to their own worldview. What was common to all holiday observances was that they took on a new dimension within the ghetto; one that was relevant and immediate, and which gave meaning to daily life. The poster discussion revolves around the holidays of Chanukah and Yom Kippur, and the meanings of the holidays – both the traditional meanings and their significance in light of ghetto realities.

Guiding question prior to the poster activity:

The attached posters and testimonies reflect the varied spiritual and cultural activities that existed in the Vilna ghetto. Try to find, in the course of the activity, additional explanations to the ones Dworzecki gave that elucidate the existence of spiritual and cultural life in the ghetto.

Posters 1, 2

Posters 1, 2[Download Handout for students]

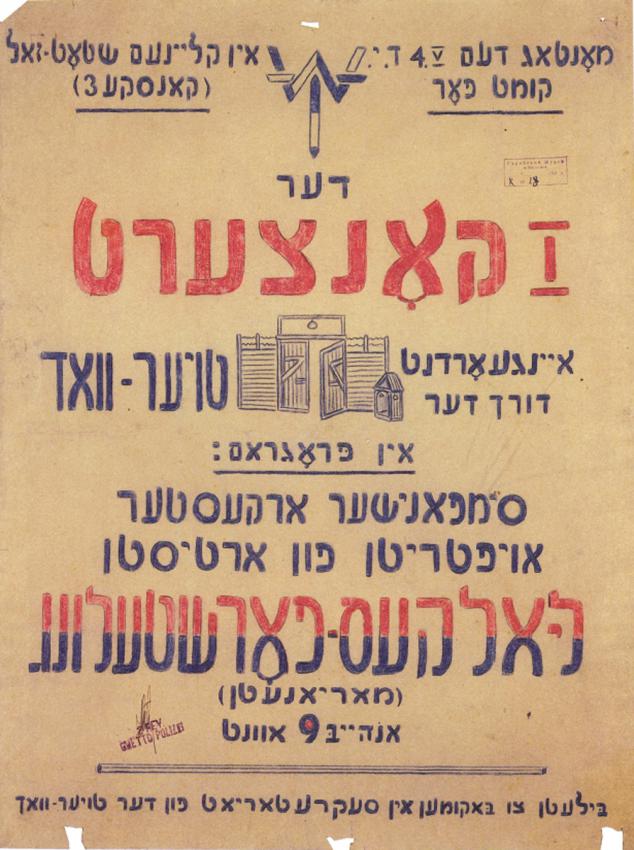

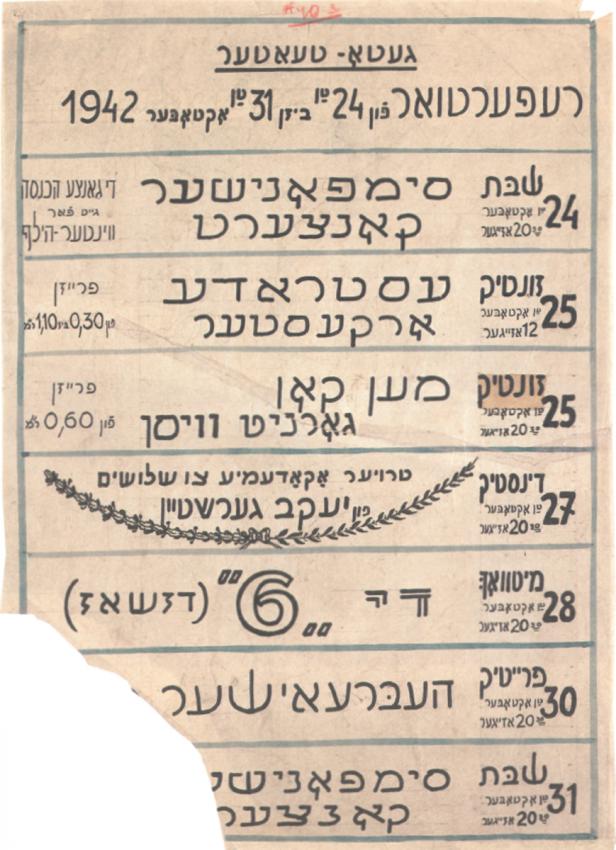

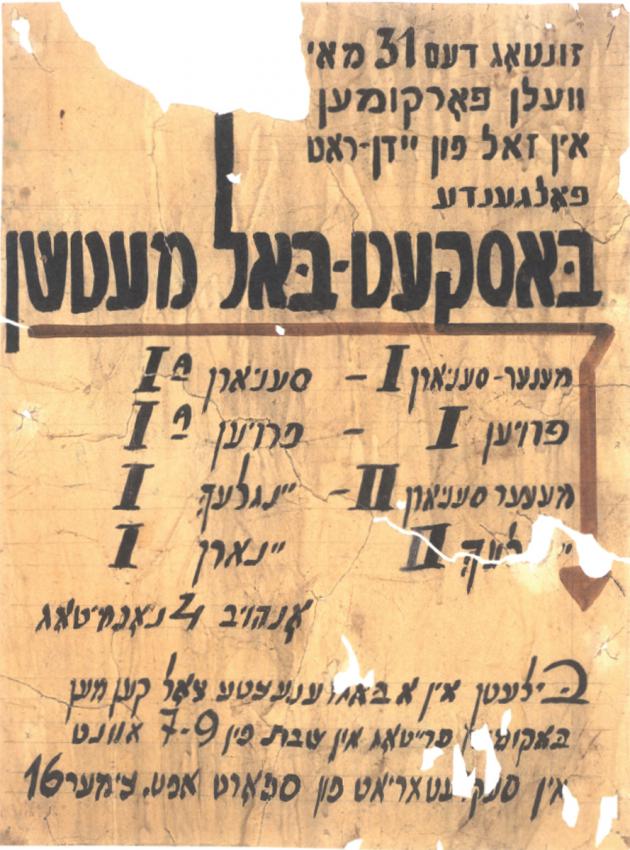

Poster 1: "Gatekeeper" Concert (Poster 3, Illustration: Poster 31) and Poster 2: Weekly Program

- study the posters in depth. How are they surprising? What questions do they raise?

- What can we learn from these posters about ghetto theater? (Relate to the information appearing on the poster and how it has been designed.)

The ghetto theater was established by the Head of the Vilna ghetto Jacob Gens, in December 1941, at the start of the so-called "Period of Stability." The theater staged plays, songs and musical productions. Many of the productions were composed within the ghetto, and expressed the themes of the daily travails of ghetto life, fears, mourning and hope. Besides the central theater, two other theaters were active, one of which performed in Hebrew. In the course of 1942, the theater staged 120 performances and received 38,000 visitors.

Look at the photo below. How does it express what the poster is publicizing?

Read the following excerpts and discuss the following questions:

- Why did people in the ghetto go to the theater? What significance did these visits have for them?

- In your opinion, why did some oppose the existence of ghetto theater?

- According to Sutzkever's description of the concert held after the "Night of the Yellow Schein (Permits)," what are expressions of life in a world of death?

- What additional meanings do the posters take on after reading the testimonies?

Ghetto News No. 30

On the occasion of the one-year anniversary of ghetto theater

15 January 1943

G. Yashonsky (Cultural Department Manager).

"[…] I wish to take this opportunity to express certain opinions for and against the theater. Critics say: Theater – this is entertainment, and in the ghetto there is no place for entertainment. Why do objectors criticize only entertainment in the theater; why do they not also object to card games, chess, literature, etc.? Only theater is forbidden. There is no logic in this […]

"One of the critics even said:' In the ghetto only one song is appropriate: El Maleh Rahamim [O' G-d, Full of Compassion, a liturgical prayer eulogizing the dead].' But if so – there is room in the ghetto for other music. The only question is, where is the limit? My personal opinion is – up until jazz music. But I am willing to entertain other opinions.

"[…] One visitor says that the theater is a refuge for people who wish to flee their homes, flee reality. This is true also for us. People want to forget what is going on at home. If it works out, they can even forget where they are for several hours, and that is to the credit of all the actors, illustrators, etc. who are capable of providing this refuge […]."

J. Gens

"[…] Before the first concert, it was said that concerts should not be conducted in a cemetery. This is true, but now life itself is a cemetery. It is forbidden to be weak. We must be strong in our spirit and our bodies […] I am convinced that the Jewish life being developed here, the Jewish fire burning in our hearts, will redeem us from these troubles."

Ruska Korchak, Flames in the Dust (Merhavia: Moreshet V'Sifrat Hapoalim, 1965), pp. 344-345.

Ruska Korzcak (1921-1988): an underground fighter and partisan and a native of Poland. Until the outbreak of World War II, she lived in Plotzek. Afterwards, she arrived in Vilna, where she joined the leadership of the Hashomer Hatzair youth group. After the underground left for the forests, Korzcak became a partisan. In December 1944, she made aliya, where she reported to leaders of the Yishuv (Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel) about the Holocaust and the Jewish underground movement. Korzcak was a member of Kibbutz Ein Hahoresh and a leader of Hakibbutz Ha'artzi and other educational programs to commemorate the Holocaust.

Jacob Gens (1905-1943): Head of the Vilna ghetto and Head of the ghetto's Jewish police. Gens was married to a Lithuanian gentile woman and rooted in Lithuanian society, but nonetheless did not attempt to evade the fate of the Jews and entered the ghetto with them, which raised the esteem in which he was held. He had the natural demeanor of a leader – a sense of Jewish identity and an ambition for power. These were put to the test in the realities of the ghetto. Gens valued communication with the residents, and to this end, he published a weekly newspaper in Yiddish entitled Ghetto News. Gens advocated developing cultural activities, and was the initiator of the ghetto theater and orchestra. In addition to the educational activities he spearheaded, Gens understood that the ghetto needed to be considered productive, and its residents should therefore work for the Germans to buy time until the war's fortunes reversed. In October 1942, the Germans demanded that the Jewish police participate in an upcoming aktion in the nearby ghetto of Oszmiana, in which they were to "liquidate" 1,500 children and non-working women. Rather than comply, he delivered to the Germans 406 chronically ill and elderly people. Gens justified his actions by claiming that if the Germans had performed the selection, they would have taken women and children vital to the perpetuation of the Jewish people. When the ghetto liquidation began, his Lithuanian friends offered to assist him in leaving the ghetto and finding a hiding place, but he refused, even though he knew what awaited him. In September 1943, Gens was murdered by the Gestapo.

"In January 1942, as the ghetto began to form… a cultural life, the first concert was staged at the hall of what had been the Reali Gymnasium [high school].

"This concert was hard to forget. It was shortly after the 'Night of the Yellow Schein Permits'. The mood in the hall was like that of when the dead are commemorated. Every word, every sound brought to mind the martyrs… people stood as if before an open grave, and listened to the strains of Chopin's 'Funeral March.'"

Avraham Sutzkever, Vilna Ghetto (Tel Aviv: Sichbi Publications, 1947), p. 107.

Avraham Sutzkever (1913-2010): a poet and partisan. During the Nazi period, he wrote more than 80 songs and poems. Sutzkever was active in selecting content for the ghetto theater productions. The Germans forced him to sort Jewish literary works that had been found in libraries throughout the city, and he and his friends smuggled books, manuscripts and artworks into the ghetto in order to save them. At the same time, Sutzkever assisted in acquiring arms for the underground. With the liquidation of the ghetto, he joined the partisans in the forests. Toward the end of the war, he helped bring Nazi war criminals to justice. He later made aliya.

Night of the Yellow Schein: In October 1941, the German Labor Office put out "yellow schein" (work permits colored yellow) for various tasks in the ghetto. Some 3,500 of these "schein," as they were known, were distributed to heads of households and workers; that is, to a working husband or wife. Anyone with one of these documents could add to it the names of their spouse and two children under 16. Family members added to the yellow schien documents were given blue notes. Some 12,000 people in total were given yellow schein or had their names added to them. Anyone in the ghetto not listed as such – about the same number again – was sentenced to death. On October 24, 1941, the first aktion took place against this group. This became known as the 'Night of the Yellow Schein.'

Poster 3

Poster 3[Download Handout for students]

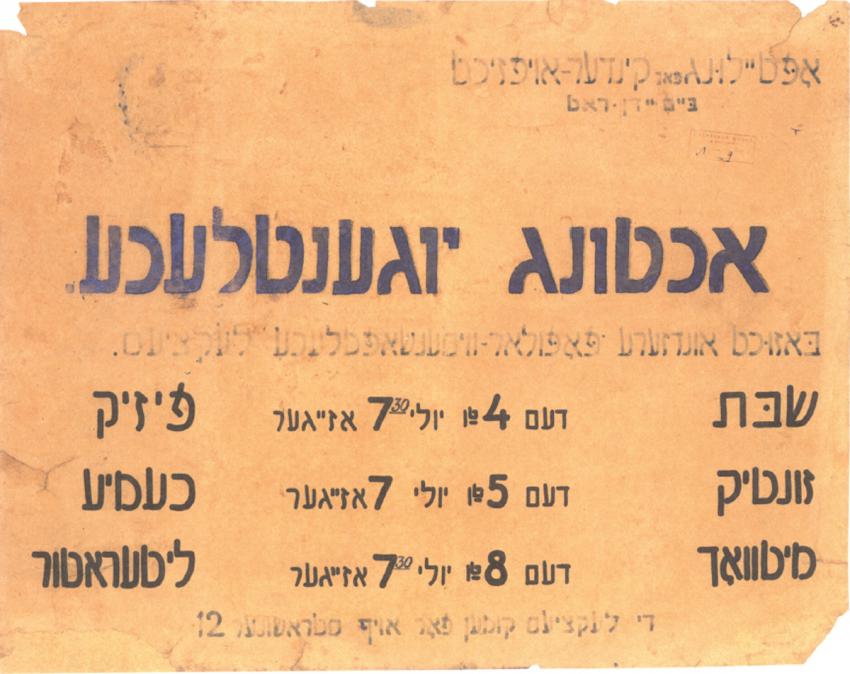

Lectures for Youth in Physics, Chemistry, and Literature

Examine this poster. To whom are the lectures directed?

Read the sources and discuss the following questions:

- What, in your opinion, motivated the ghetto's Youth Department to conduct these lecture series?

- What would cause youth to attend these lectures and generally to bother learning in the ghetto?

- How do the following excerpts reflect the ruptures and difficulties of ghetto life?

- What challenges did educators face in the ghetto?

- Why, in your opinion, does Dworzecki emphasize that "30 meters from where a gemarah test was taking place, an SS man stood guard at his watch"?

The first schools within the ghetto opened immediately upon the ghetto's creation. The ghetto had two elementary schools, with 700-900 students aged 5-12. In addition, the ghetto had a religious school, a high school and nursery schools. Subjects taught included Yiddish and Hebrew, religious studies, Jewish history, general history, math, geography and science.

"For me, the drive to learn was a rebellion against the present, in which learning was hated and working prized. I was determined to live in the future, and not the present. If of 100 children in the ghetto my age, ten could learn, I had to be among them, to take advantage of this opportunity. "

Yitzhak Rudashevsky, Diary of a Vilna Youth (Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1969), pp. 88-89.

Yitzhak Rudashevsky (1927-1943): a teenager in the Vilna ghetto who left behind a sensitive description of war events. Rudashevsky, an only child, lived relatively well with parents concerned for his continuing education. When the German Army occupied Vilna, he was not yet 14. After the ghetto was liquidated, Rudashevsky went into hiding with his family. After two weeks, however, their hideout was discovered and the family was sent to Ponary, where they were murdered.

"Mira Bernstein, the onetime principal of the Reali Gymnasium in Vilna, marched together with her pupils on the day they were forced into the ghetto.

"[…] That evening, Mira gathered the children and read them a story by Sholem Aleichem.

"[…] Each morning, Mira would count the children, and each morning there would be fewer. At night the murderous hand would claim victims, but the next morning the learning continued."

Avraham Sutzkever, Vilna Ghetto (Tel Aviv: Sichvi Publications, 1947), p. 84.

Mira Bernstein (1908-1943): a graduate of the Yiddish Seminary for Teachers in Vilna, the only one of its kind in Poland between the two world wars. She taught in schools in Vilna. In 1939, she was appointed principal of the Yiddish Gymnasium. With the establishment of the ghetto, Bernstein became an important figure in organizing the ghetto's educational system, running programs under difficult conditions as long as the ghetto existed. Among other projects, she staged children's plays and was active in the ghetto's "Youth Club." Bernstein was also a member of the ghetto underground, but toward the time the ghetto was to be liquidated, she did not leave through the sewers, as others did, fearing that due to her poor health she would be a burden to the others. She was murdered in Majdanek.

Avraham Sutzkever (1913-2010): a poet and partisan. During the Nazi period, he wrote more than 80 songs and poems. Sutzkever was active in selecting content for the ghetto theater productions. The Germans forced him to sort Jewish literary works that had been found in libraries throughout the city, and he and his friends smuggled books, manuscripts and artworks into the ghetto in order to save them. At the same time, Sutzkever assisted in acquiring arms for the underground. With the liquidation of the ghetto, he joined the partisans in the forests. Toward the end of the war, he helped bring Nazi war criminals to justice. He later made aliya.

"In the period following the ghetto's establishment, a cultural struggle broke out regarding the character and essence of the schools, their educational aims, the choice of teachers and the curriculum. It was a struggle for the soul of the ghetto child: What would be the national and collective goals toward which children would be educated, that would comprise their spiritual legacy were they to be freed? Questions arose as to the extent the ghetto school should emphasize Hebrew, Yiddish, Eretz Israel, Tanach Bible studies, Jewish and world history; which periods and which heroes demanded the special attention of the educators. It was determined that that the language of instruction for all schools and all classes would be Yiddish. However, Hebrew language and literature would be taught as well, emphasizing the language's great value to the Jewish nation and culture in all its generations. Jewish history would be a central subject in school, studied in parallel with world history. Tanach would also be a fundamental subject in the school system."

Meir (Mark) Dworzecki, The Jerusalem of Lithuania in Revolt and in the Holocaust (Tel Aviv: Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael, 1951), pp. 216-217.

"The ghetto had a network of schools, in which about 3,000 children learned. These schools included religious studies; while not mandatory, in practice all the children sat in on these lessons. The Charedi [ultra-Orthodox] parents, however, chose to create special schools, where they would receive the distinct religious scholarship... Classes were held at times of day that would enable attending the general schools as well. Teachers and public figures in the ghetto did not consider the religious schools competition for the more general-curriculum schools, but rather a complement to them… From time to time, public tests were conducted. They would sit children around tables. The rabbi sat in the middle, testing them on the material they had learned, and even invited guests who could ask questions. At the end of the test would be a seudat mitzvah [festive meal]. I was present at one of these tests on the Talmudic topic of "Yiush Shelo Mida'at" (giving up hope unknowingly). About thirty meters away from this gemarah test, an SS man stood guard at his watch."

Dworzecki, The Jerusalem of Lithuania, pp. 222-223.

Posters 4, 5

Posters 4, 5[Download Handout for students]

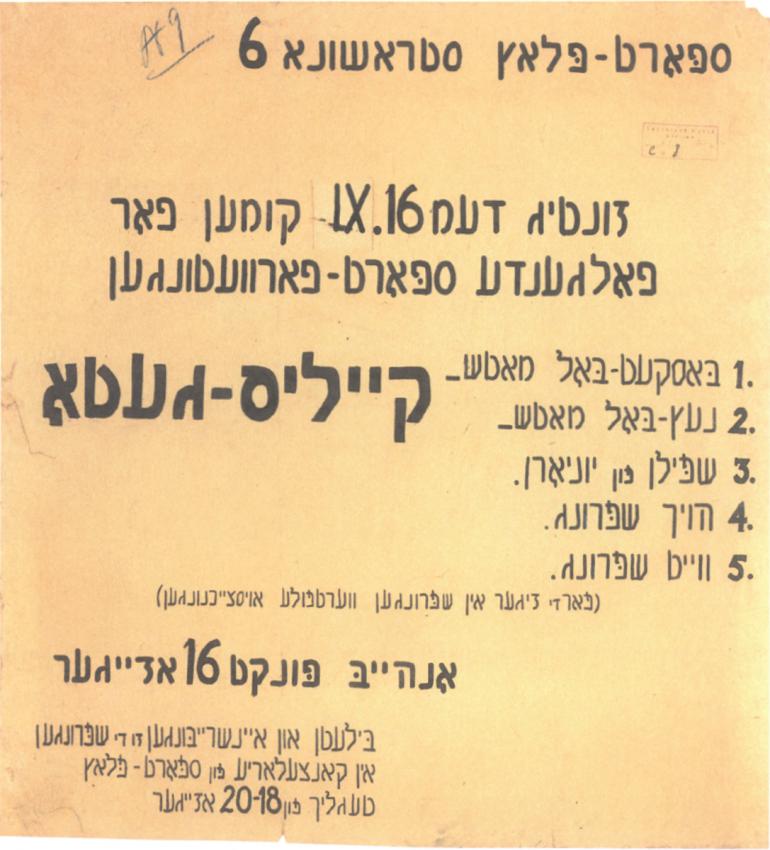

Sporting Competitions (Poster 18)

- Study these posters. What surprises you the most and why?

- How many different sports are competing? What does this indicate?

In July 1942, there were 28 clubs for gymnastics, boxing and other sports in the Vilna ghetto. The ghetto had more than a thousand athletes out of a total of 20,000 residents. These athletes staged contests in soccer, tennis, boxing, long jump and running races down the ghetto's narrow streets.

"The ghetto even had a sports field. Workers went to great efforts to create it – clearing, lining and expanding the field by destroying adjoining buildings that were unfit for use… and indeed it was announced that the next day there would be a festive opening ceremony for the sports field – entrance by invitation only.

"At the ceremony, representatives of the Judenrat and the police were present, including Salk Dessler [a Jewish policeman] and Yosef Moshkat [Deputy Head of the Judenrat]. Moshkat said: 'If in years to come one will wish to trace and understand our life in the ghetto, and no documentation remains, this field will faithfully testify to the essential vitality and the unbridled spirit of life that dwells within us…'

"… And indeed, people in the ghetto began to engage in sports. Crowds of youngsters gathered on the field, and even prepared for a race around the ghetto….

"Theater, elegance, sport – these bring a growing sense of optimism. A growing number of voices are heard – in spite of it all, we will outlive our enemies and win…"

Ruska Korzcak, Flames in the Dust (Heb.), (Merhavia: Moreshet V'Sifrat Hapoalim, 1965), pp. 108-109

Ruska Korzcak (1921-1988): an underground fighter and partisan and a native of Poland. Until the outbreak of World War II, she lived in Plotzek. Afterwards, she arrived in Vilna, where she joined the leadership of the Hashomer Hatzair youth group. After the underground left for the forests, Korzcak became a partisan. In December 1944, she made aliya, where she reported to leaders of the Yishuv (Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel) about the Holocaust and the Jewish underground movement. Korzcak was a member of Kibbutz Ein Hahoresh and a leader of Hakibbutz Ha'artzi and other educational programs to commemorate the Holocaust.

"Most amazing of all is the sports field… Every day, youth use the field to perform gymnastic exercises and compete in various sporting events. I couldn't believe what I was seeing. I wanted to shout, 'Is this a dream or reality?' I didn't know whether to be happy or to cry about this paradox. Perhaps those who live this way are right, acting as if the horrors outside do not exist, and refusing to see the walls that surround us. Perhaps they have forgotten that we are in the grip of an iron fist, liable at any moment to close around us and crush us like flies."

Gregory Schorr, Notes from the Vilna Ghetto 1941-1944 (Heb.), (Tel Aviv: Association of Former Residents of Vilna and the Environs in Israel, 2002), pp. 51-52.

Gregory Schorr (1888-1945): journalist and political activist. In the ghetto, he sorted army uniforms for the Germans. He wrote and hid a diary in which he described events of the ghetto. An anti-Nazi Lithuanian would secretly enter the ghetto and smuggle out his notes, and later hid them under the floor of the University of Vilna, where he worked. After the war, Schorr's daughter successfully smuggled out a copy of the diary from the Soviet Union. The diary was written on cigarette paper in encrypted text. Schorr was murdered at the Stutthof concentration camp just before its liberation.

- What message was being conveyed by sports participation and to whom?

- "and even prepared for a race around the ghetto": Why did Ruska use the word "even"?

- What challenges and complexities accompanied the very existence of these competitions and sporting events?

- Do the posters take on adding meaning after reading the sources?

Poster 6

Poster 6[Download Handout for students]

Lottery for the "Winter Assistance" initiative (Poster 34)

Study the poster. In your opinion, what motivated people to participate in this lottery?

How is this lottery paradoxical?

Study the following testimonies and try to answer this question.

"The ghetto has no 'tomorrow,' rather, it lives from moment to moment. Each morning, man awakes from a restless slumber: his first thought is – the night has passed, who knows what this day will bring?"

Ruska Korczak, Flames in the Dust (Heb.), (Merhavia: Moreshet V'Sifrat Hapoalim, 1965), pp. 344-345

Ruska Korzcak (1921-1988): an underground fighter and partisan and a native of Poland. Until the outbreak of World War II, she lived in Plotzek. Afterwards, she arrived in Vilna, where she joined the leadership of the Hashomer Hatzair youth group. After the underground left for the forests, Korzcak became a partisan. In December 1944, she made aliya, where she reported to leaders of the Yishuv (Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel) about the Holocaust and the Jewish underground movement. Korzcak was a member of Kibbutz Ein Hahoresh and a leader of Hakibbutz Ha'artzi and other educational programs to commemorate the Holocaust.

- What difficulty does Ruska Korczak depict in her testimony? What was the effect of this difficulty?

"Perhaps because of the great uncertainty surrounding the future, people lived fully in the moment, enjoying fleeting instants of emotional satisfaction, and forgetting the entire world to enjoy the few bright moments. Romances blossomed, couples looked for places to be alone for a few hours, and rabbis officiated at marriages of young couples…."

"On January 15, 1943, a group of young adults gathered… to celebrate the birthday of… Lyova… Lyova had turned 28. She was accustomed to celebrating her birthday every year

with a nice party. This evening she sensed that this would be her last birthday. She burst out in tears and we, her friends and family, cried with her.

"… Lyova told us that she had a fiancé in Eretz Israel… and said again that she was certain she would never again see her beloved and this would be her last birthday; perhaps some will survive, and those people will celebrate their birthdays and be happy, but she would not. Those who remain might take the opportunity to remember her and other beloved ones who had been murdered, and remember this day of January 15, 1943, and the birthday celebration in the ghetto, in a small, dark room. Her will and her wish was for this evening to be engraved in the memories of all, as a sort of dissonance to the bitter and horrible reality in which we were mired. In the end, the evening took on a more upbeat tone, and we began to form dreams for the future: how the world might look once Nazi Germany was defeated, how people might then relate to life, and how great might be the joy of those who remained…."

Alexander (Xenia) Rindzionsky, The Destruction of Vilna (Heb.), (Tel Aviv: Beit Lohamei Hagetaot Vehakibbutz Hameuchad, 1987), p. 110.

Upon the liquidation of the ghetto, Lyova and her family were murdered in Ponary, mere days before Vilna's liberation.

Alexander (Xenia) Rindzionsky: fought with the partisans in the forests outside Vilna. After he was wounded, he contributed actively to an underground newspaper, and in the spring of 1944, the leader of the partisan brigade asked him to document Jewish life in Vilna during the Holocaust. After the war, he worked at the Jewish Museum in Vilna; in 1959, he made aliya.

- What, in your opinion, do the ghetto birthday party and the ghetto lottery have in common?

Note: a birthday party has two aspects: One – to mark the end of a period in one's life; and two – especially among youth – to mark getting older, while opening possibilities for the future.

Funds from the ghetto lottery were donated to "Winter Assistance" – one of the three ghetto aid societies. This organization's goal was to collect winter clothes for the needy. In the ghetto were those who could not work and did not receive food rations. Social aid programs included free meals at public kitchens, financial assistance, free medical care, full or partial rent exemptions, and more. Unlike in some other ghettos, in the Vilna ghetto people did not die from hunger or cold – partly thanks to these aid institutions.

"Worth noting: The students from the school at Siauliai Street 1 raised from among themselves 209 rubles for their fellow students who came to school hungry. They asked their teachers to take the money and arrange breakfast for their hungry friends."

"Diary of Moshe Olicki," in Leah Langelben (ed.), Live and Learn (Heb.), (Jerusalem: The Institute for Holocaust Studies, 2014), p. 334.

- Why does Olicki think that the event is "worth noting"?

- What is the significance of the fact that Jews engaged in mutual aid efforts in the ghetto?

- Does this poster gain added significance after reading the testimonies?

Poster 7

Poster 7[Download Handout for students]

Chanukah Party of the "Brit Ivrit (Hebrew Covenant)" Union in the ghetto (poster 43)

- Study the poster. What about ghetto life can be learned from it?

- What questions does this poster raise?

"5 December, 1942

"[…] We've already written, frequently, that the ghetto is very careful about safeguarding traditions. Every holiday is enthusiastically celebrated here, regardless of the situation. On Thursday, December 3, an evening to celebrate Chanukah took place at the theater hall, organized by the police.

"[…] An additional Chanukah party was organized here by the religious movements […] in the ghetto it was permitted to light only one Chanukah candle for all eight days. The reason given was that candles were precious and people could not allow themselves to use them up.

"[…] on the 13th of the month, the children organized a Chanukah play at the ghetto theater. At six on that same day at the theater hall, a Chanukah party took place filled with artistic programming.

"On Friday the 11th of the month, the children's club organized a Chanukah party with latkes.' The evening transformed from a Chanukah event to an impressive event of Vilna's children from both religious and secular schools. To enable participation, many events were planned in the ghetto. But this last event turned a Chanukah miracle into a miracle of youth, who thirsted for a new life of freedom."

Herman Kruk, The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps, 1939-1944 (New Haven: Yale University, 2002), pp 422-424.

"On the evening of Simchat Torah I came, by invitation of the rabbi, to the hakafot [circuits made with the Torah on the Jewish festival of Simchat Torah] in the house that served as the synagogue and was now the music school. Remnants of the yeshiva boys and Torah-learners gathered, including some children. They sang and danced… Here, amidst this anguished group, in a destroyed synagogue, we joined the congregation of Israel – not only those with us that day, but also those who had died, in the congregation of the holy and pure. Thousands upon thousands, as well as with the previous generations. With this joy, we acknowledged the previous generations, the beautiful generations, the generations that were worthy of life. We felt on that day, with our songs of praise, that we were sanctifying God as our forefathers did. And I, an errant soul of Israel, feel my roots here... I know that the nation of Israel is alive and will live.. It is enough that we merited to be of this people, and each day that God gave us in His kindness this absolute gift, we receive with thanks and gratitude to Him."

Zelik Kalmanovitch, Diary of the Vilna Ghetto and Writings Found in its Ruins (Heb.), (Tel Aviv: Moreshet, 1977, p. 83.

- Why, in your opinion, did people in the ghetto celebrate holidays?

- Did holidays gain special significance within the ghetto?

"… the goal of the 'Hebrew Covenant' – was to create within the ghetto, by means of the living Hebrew language and with inspiration from the vision of a free life in the homeland of Eretz Israel, an uplifting disconnect from the miserable ghetto life."

"… its first parties were held in the hall of the public kitchen – known as "Tzioni" – at Strashun St. 2, in the presence of dozens of members. Initial events were dedicated to the memory of Josef Trumpledor and Eliezer Ben-Yehuda.

"Quickly these events caught on among the wider public, many of whom thirsted for the Hebrew language and the distant celestial voice from the Land of Israel. Demand grew, and the events were hosted in a larger facility: the ghetto theater. At times, the audience numbered as many as 600. Gatherings of the 'Hebrew Covenant' served as a stage for ideas from the resistance movements, many of whose members belonged to the 'Hebrew Covenant.' Parties were held for Passover (Moshe striking the Egyptian)… Shavuot (Receiving the Torah), Chanukah (the Hashmonian Rebellion), Purim (the fall of Haman), Masada (the War of the Desperate), as well as gatherings in memory of Bialik, Herzl and Ahad Ha'am. One party was dedicated to contemporary Hebrew poetry. Each party included one or more lectures, choral singing, readings from the Tanach and Hebrew poetry recitations.

"In difficult times, when heavy clouds covered the ghetto, Dimantman [a Jewish educator] would say to his fellows: 'Until the ghetto's very last day, the sound of the Hebrew language should be heard.'"

Meir (Mark) Dworzecki, The Jerusalem of Lithuania in Revolt and in the Holocaust (Heb.), (Tel Aviv: Mifleget Poalei Eretz Yisrael, 1951), pp. 229-230.

Meir (Mark) Dworzecki: a Jewish doctor in the Vilna ghetto. During World War II, he served in the Polish Army and fell captive to the Germans. After escaping from a POW camp, he returned to Vilna. In addition to his work as a doctor, he was a member of the ghetto underground, but before he was able to escape to the forest and join the partisans, he was sent to a forced labor camp in Estonia. At this camp, he attempted to save sick prisoners who were liable to be murdered by masking their illnesses. After the war, he made aliya (immigrated to Eretz Israel), where he worked to commemorate the efforts of Jewish doctors to save lives during the Holocaust. As an established historian, he also endeavored to document the Nazis' medical war crimes. Dworzecki, who testified at the Eichmann trial, died in 1975.

This poster, written in Hebrew, differs from other posters written in Yiddish, reflecting the various political and ideological strains that began many years before the war and remained intact during the war years. The "Hebrew Covenant" Union was founded in the fall of 1941 to expand the study of Hebrew and instill Zionist content in educational and cultural activities. The creation of this union was accompanied by political struggles within the ghetto between Zionist and anti-Zionist factions about how to educate youth.

- Why did Dimantman think that "'Until the ghetto's very last day, the sound of the Hebrew language should be heard"?

- What was the significance of holding Zionist activities in the ghetto in Hebrew?

- What, in your opinion, caused the growth in the number of participants in Zionist conferences and other events?

- Does this poster gain added significance after reading these testimonies?

Posters 8, 9

Posters 8, 9[Download Handout for students]

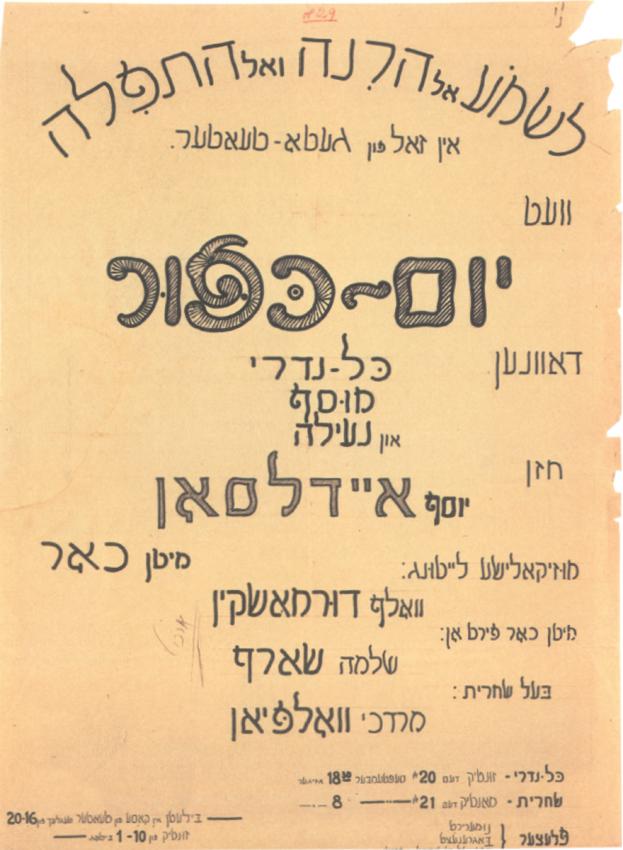

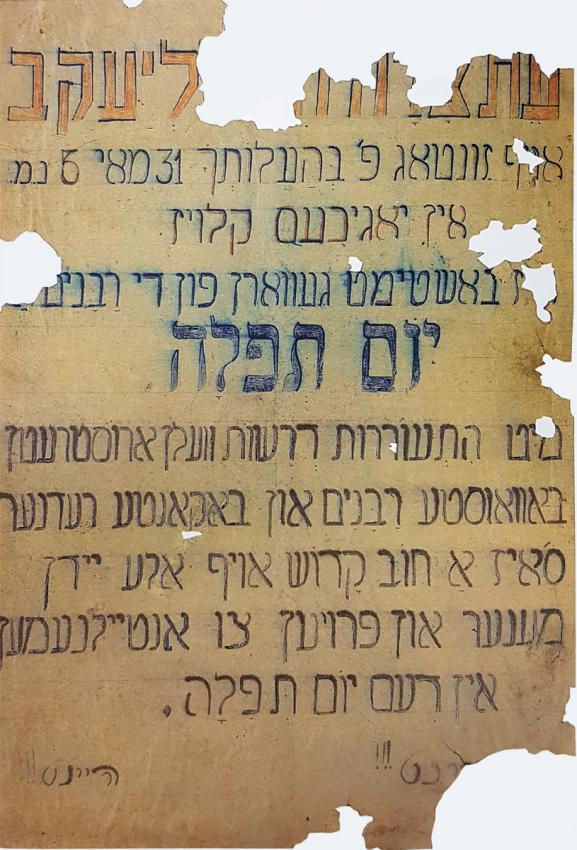

Poster 8: Yom Kippur Service and Poster 9: Prayer Day

Study the posters and note the verses used in the titles. What do these verses mean? Do they gain significance in light of the ghetto reality?

In Vilna, as in every other city in which Jews lived, there was a large religious population. Ghetto conditions created great hardships for religious compliance. For instance, Sabbath observance was impossible due to demand for forced labor seven days a week. In spite of this, attempts were made to observe wherever possible: The ghetto contained three shetibl synagogues that filled up on the holidays, and on regular days held elementary school and yeshiva classes. Before Passover, matzahs were baked, on Sukkot a few sukkahs were built, and hakafot (circuits) were made on Simchat Torah.

"30 September 1941

Kol Nidre

"This Yom Kippur eve in the ghetto is unique. People cook in a large pot in their homes as if nothing has happened, they launder and clean (as if nothing is happening outside).

"On the ghetto gate, the Germans have hung a sign "Seuchengefahr" (Danger of Plague). Plague: that is, one should flee this place as from lepers. The Germans will not enter here. And if they do not enter, we will find rest.

"Workers returning from the city tell that the Germans released them for Yom Kippur… [The residents who are going to hear "Kol Nidrei," the opening prayer of Yom Kippur ] go to Kol Nidrei. The Kol Nidrei prayer needs to be completed by 6:30pm, by order of the Judenrat. Kol Nidrei is recited here in the dark. The study hall is filled beyond capacity, and people stand on the stairwell, in the entranceway. In the yard, on the street, everyone is sad and harried. Jews come to my library, asking to borrow holiday prayer books.

"At the time of Kol Nidrei, several attacks took place. People fainted. In short: Yom Kippur, with all its details and particularities.

Herman Kruk, The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps, 1939-1944 (New Haven: Yale University, 2002), pp (?)

"21 September, Yom Kippur 1942

"A year ago today we were already past the first "clearing out" but had not yet endured the notorious first aktion of Yom Kippur. My nerves still jangle when I am reminded of that Yom Kippur.

"This year, the eve of Yom Kippur was characterized by great celebration […], now, looking back a year later, I write so much easier. This is my remembrance after a long stretch of aktionen that took place at that time. […] This year preparations were made for Yom Kippur, but these were influenced by the events of the previous year. In the ghetto, there were many minyanim (prayer quorums). The peak of this was the prayer in the theater hall, organized by the theater workers themselves. This service became a Yom Kippur parade. Here prayed the chazzan [cantor] of the Great Synagogue, [Yosef] Eidelson, accompanied by a special choir. Entrance required tickets.

"[…]The atmosphere was festive. After Kol Nidrei [Dr. Tzemach] Feldstein announced that Mr Gens would speak. Gens said, 'We will start by saying kaddish [the mourner's prayer] for those who were and are no more. We have endured a difficult year; let us pray to God that the upcoming year will be easier. We need to be strong, disciplined and hardworking.' At the start of Gens' speech, bitter crying was heard: The pain of Ponary."

Herman Kruk, The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. Chronicles from the Vilna Ghetto and the Camps, 1939-1944 (New Haven: Yale University, 2002), pp. 360-361.

On Yom Kippur, October 1, 1941, a surprise aktion was conducted in the two ghettos in Vilna. In the afternoon, when the synagogues were packed with worshippers, Germans and Lithuanians entered the smaller ghetto and began to make arrests. The aktion surprised the ghetto residents, and the Germans were therefore able easily to round up hundreds of people from synagogues, homes and streets. The aktion continued into the evening. Those taken in the aktion, some 1,700 people, were sent to the Lokishki prison and from there to Ponary. That same afternoon, an aktion in the larger ghetto resulted in 2,200 Jews rounded up and sent to the Lokishki prison and to Ponary.

Jacob Gens (1905-1943): Head of the Vilna ghetto and Head of the ghetto's Jewish police. Gens was married to a Lithuanian gentile woman and rooted in Lithuanian society, but nonetheless did not attempt to evade the fate of the Jews and entered the ghetto with them, which raised the esteem in which he was held. He had the natural demeanor of a leader – a sense of Jewish identity and an ambition for power. These were put to the test in the realities of the ghetto. Gens valued communication with the residents, and to this end, he published a weekly newspaper in Yiddish entitled Ghetto News. Gens advocated developing cultural activities and was the initiator of the ghetto theater and orchestra. In addition to the educational activities he spearheaded, Gens understood that the ghetto needed to be considered productive, and its residents should therefore work for the Germans to buy time until the war's fortunes reversed. In October 1942, the Germans demanded that the Jewish police participate in an upcoming aktion in the nearby ghetto of Oszmiana, in which they were to "liquidate" 1,500 children and non-working women. Rather than comply, he delivered to the Germans 406 chronically ill and elderly people. Gens justified his actions by claiming that if the Germans had performed the selection, they would have taken women and children vital to the perpetuation of the Jewish people. When the ghetto liquidation began, his Lithuanian friends offered to assist him in leaving the ghetto and finding a hiding place, but he refused, even though he knew what awaited him. In September 1943, Gens was murdered by the Gestapo.

Herman Kruk (1897-1944): a leader of the Bund movement in Poland and a chronicler of the Vilna ghetto. His diary provides a detailed description of everyday life in the ghetto. Kruk managed the ghetto library and was forced to work at sorting the stores of Jewish literature that were found in the city's libraries. He and his friends managed to smuggle manuscripts and important books into the ghetto and thereby prevent them being transferred to Germany. Upon the liquidation of the ghetto, he was sent to the Klooja camp in Estonia, where he continued to keep a diary until the day before he was murdered, September 18, 1944, only a few days before liberation.

"Sunday the 20th. Yom Kippur Eve. An aura of sadness pervades the ghetto. It is a sort of festive sadness. Though now, as before the ghetto, I am far from observance, nonetheless this bloodstained and sad yom tov [holiday] is engraved on my heart. This evening was so sad for me! At home, we sit and cry, remembering the past […] we kiss, bless one another and soak one another with our tears […]. I escape outside and it's more of the same: Sadness flows in the alleyways, the ghetto is saturated with tears. Hardened ghetto hearts, that in the midst of their worries had no time to break down, burst out this evening with cries of bitterness […] This was an evening of melancholy, of dark sadness."

Yitzhak Rudashevski, The Diary of the Vilna Ghetto (Ghetto Fighters House and Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1973), p. 56.

Yitzhak Rudashevsky (1927-1943): a teenager in the Vilna ghetto who left behind a sensitive description of war events. Rudashevsky, an only child, lived relatively well before the war with parents who were concerned for his continuing education. When the German Army occupied Vilna, he was not yet 14. After the ghetto was liquidated, Rudashevsky went into hiding with his family. After two weeks, however, their hideout was discovered and the family was sent to Ponary, where they were murdered.

- According to the poster and the testimony, what was the intended atmosphere for the Yom Kippur prayers? What happened in practice at the time of the prayers?

- What aspects of Yom Kippur were maintained and what changed in the ghetto?

- Does the poster gain added significance after reading the testimonies?

- Where are the questions/quotes for this poster?

Summary: Discussion on the significance of cultural and spiritual life in the ghetto

Summary: Discussion on the significance of cultural and spiritual life in the ghettoBased on the group activity, discuss with the students the following questions:

- How do the posters and sources reflect the ruptures taking place in the lives of Vilna Jews?

- How do they reflect the attempt to continue cultural and spiritual life?

With the students, listen to the song "We Live Forever" that was composed and sang in the ghetto, and look at the artwork "Ghetto," created by Shmuel Bak

Discuss how both the song and the artwork reflect life in the Vilna ghetto and the significance of maintaining cultural and spiritual life there.

"We Live Forever"

Lyrics: Leyb Rozental

Composer: Unknown

This song was performed in one of the last cabarets in the ghetto, in August 1943. Most cabaret songs became popular among the ghetto inhabitants.

We live forever, the world's ablaze

We live forever through these awful days

Despite the efforts of our enemies

Who wish to bring us crying to our knees.

We live forever and we are here!

We live forever, we have no fear.

We want to live now, and to live on

To survive all these awful moments

We live forever and we are here!

In this drawing, the ghetto appears isolated, as if the rest of the world has disassociated from it, and like its inhabitants, it is marked in disgrace, with a yellow star. The city remains standing; the church bell towers of its Christian quarter are erect and upright, in contrast with the crumbling houses of the ghetto. The city vista is bathed in yellow light, an echo of the color of the star.

The city is shaped like a gravestone, as are its houses. Bak is likely hinting that the house, usually a symbol of life and family warmth, has become a symbol of death. Possibly, this reversal of roles hints at the complex reality of life and death within the ghetto.

From among the testimonies and posters, ask the students to select one that holds special meaning for them in terms of their identity, heritage or traditions.

- Shmuel Bak was born in Vilna in 1933, to a middle-class family. His mother discerned his artistic talent from the age of three and encouraged him to pursue it. With the expulsion to the ghetto, his father was send to a work camp while he and his mother hid in a monastery, but because the Germans were suspicious, they were forced to escape and return to the ghetto.

In March 1943 the poets Avraham Sutzkever and Shmaryahu Kaczerginski invited the nine-year-old Shmuel to present his artwork at an exhibition held in the ghetto.

Historical Appendix

Historical AppendixVilna, also known within the Jewish world as the "Jerusalem of Lithuania," is today the capital of Lithuania. In the past, the city was ruled by Poland and Russia. Vilna was founded in the twelfth century at the confluence of the Vilnius and Neris Rivers, and served as a commercial center. In 1323, the city became the capital of the Lithuanian kingdom, and after the unification of the kingdom of Poland and Lithuania in 1369 it fell under the influence of Catholicism and Polish culture – a trend which continued even after its annexation to Russia in 1795, in the course of the final partition of Poland. In the nineteenth century, Vilna participated in the Polish rebellion against Russia, and Russia responded with a massive "Russification" of the city's residents.

The identity of the city remained ambiguous throughout the twentieth century, and this ambiguity intensified at the time of World War I: In September 1915, Germany conquered the city and ruled over it until the war's end in November 1918. When the German forces retreated from the city, a Lithuanian government was established, but it disbanded upon Vilna's conquest by the Poles. In 1920, the Red Army conquered the city and the Soviets allowed the formation of local Lithuanian rule. Shortly afterwards, however, Vilna was again annexed to Poland, which was a source of ongoing tension between Poland and Lithuania between the two world wars.

History of the Jews in Vilna:

The first evidence of a Jewish presence in Vilna is from 1527, when town citizens petitioned the Polish king Zigmund the First to ban Jews from settling there. Because the aristocracy required Jewish finance, however, certain Jews were permitted to live in the city. Within a short time additional Jews joined them, and by 1568 the city had an identifiable Jewish community, albeit one subject to various legal restrictions. Led by local students, the non-Jews refused to accept the presence of a Jewish community, continuously attacking them and destroying their property. Despite this, the Jewish community in Vilna blossomed in population, prosperity and spirituality.

In the seventeenth century, the Jewish population of Vilna grew tremendously on the strength of two waves of immigration, from Prague and from Frankfurt, from where Jews had just been expelled. Among the immigrants to Vilna were Torah scholars and wealthy Jews. The Jewish population reached 3,000 out of a total city population of 15,000. Shortly after, refugees from the riots of 1648-1649 began to stream into the city. These refugees were of low economic status, and the Jewish community mobilized to assist them in any way possible. In 1652, the Jewish community in Vilna received a formal seat in the conference of Lithuanian Jewish communities.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, after the city recovered from war damages, the Jewish community regained its strength. Within a few years, Vilna became one of the most important spiritual centers in Europe, boasting first-rate Torah scholars. The most well known of these spiritual leaders was Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman (1720-1797), known as the "Vilna Gaon [Genius]."

The Vilna Gaon, who was recognized as a gifted scholar from a young age, was an expert in Torah, Mishnah and Talmud – both the Written and Oral Law – and was known as an expert in kabbalah [Jewish mysticism]. In addition, the Vilna Gaon learned secular subjects, such as algebra, geometry, medicine and other fields. Even though he had no formal position in the community, Torah scholars flocked to him, and he became a dominant figure in Vilna and throughout the Jewish world. The influence of the Vilna Gaon on Judaism can be felt to the present day.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Vilna Gaon stood at the head of a struggle between the Vilna community and the Hassidic movement, which was founded in Galicia (Poland) and spread quickly throughout Eastern European Jewish communities. In 1772, the local Jewish community in Vilna, under the leadership of the Vilna Gaon, closed the local Hassidic synagogue, and even excommunicated its members. Vilna became the center of the "Misnagdim [Opposers]" movement who fought against Hassidism and its values.

During this period, the Jewish community of Vilna was destabilized, for a number of reasons. Firstly, following the partition of Poland in 1795, Vilna was annexed to Russia, but the Jews of Vilna participated in and helped fund uprisings against the Russians. Secondly, the attempts by both Hassidim and Misnagdim to sway the new government in their favor led to external meddling in the internal affairs of the Jews. This involvement compromised the authority of the Jewish community. Another unsettling development was the influence of the European Enlightenment movement on the Jewish community, further heightening the existing internal tensions. Jews influenced by the Enlightenment strove to integrate with the general public, and believed that by adopting secular culture, practices and aspirations, the Jews would receive equal rights where they lived.

The Jewish Enlightenment movement in Eastern Europe raised objections from the tradition-minded leaders of the Jewish community. The Enlightenment Jews of Vilna, for their part, did not hold back from expressing their beliefs. On the contrary, they saw great value in spreading Enlightenment ideas in Vilna due to its leading status in the Jewish world. Despite the opposition of the traditional movements within the community, in the nineteenth century Vilna became a center for the Enlightenment movement and a focal point for many youth and writers. Even during the years of Vilna's growth as an Enlightenment hub, however, it remained an important center for traditional Judaism.

During the reign of Tsar Nikolai the First (1825-1855), decrees were enacted against the Jews of Russia, including those living in Vilna. Tsar Alexander the Second (1855-1881) rescinded these decrees, among them the order limiting the streets within a city on which Jews could reside. Following the Tsar's murder by revolutionaries in 1881, however, attacks on Jews grew in frequency. In 1881, soldiers rampaged in Vilna, destroying Jewish-owned stores. In response, Jews organized "self-defense" groups and thus managed to repel their attackers and turn them over to the police.

Due to the many restrictions on Jews, including forbidding them to settle in border areas, the Jewish population of Vilna grew. In 1897, 64,000 Jews lived in Vilna, more than 41 percent of the city's overall population. This population boom increased crowding and intensified economic distress, which brought about waves of emigration from Vilna to the United States, South Africa and Eretz Israel. The difficult economic circumstances and social issues created fertile ground for spreading socialist ideas. In 1897, the Bund – the socialist party of the Jewish worker – was established in Vilna. In light of the situation, another sentiment awakened: that of the Jewish nationalism, and Vilna became an important focus of Zionist activity. Vilna was a center of Yiddish and Hebrew literature and journalism, adding to the city's status as a lively hub of political and cultural activity. For instance, Vilna was known for its Strashun library, one of the most important Jewish libraries in Eastern Europe.

World War I had grave consequences for the Jewish population of Vilna: The occupying German government introduced policies of heavy economic discrimination, and dozens of Jews were murdered in pogroms initiated by the Polish Army when they gained governmental control at the war's end.

As the government stabilized, there were 46,000 Jews in Vilna, 36 percent of Vilna's overall population. Despite the economic difficulties, the community recovered and within a short time Vilna was restored as a successful center of religious, cultural and social life. In this era, several yeshivas, a gymnasium (high school) and a teacher-training institute were among the Jewish educational institutions. Unlike in other Polish cities, most Vilna Jewish youth learned in one of these affiliated institutions, in which the spoken language was either Hebrew or Yiddish, in addition to Polish. In the period between the world wars a Hebrew-language culture developed, as well as cultural activities in Yiddish. By 1931, there were 17 Jewish newspapers, among them five dailies. The city had Yiddish theater, a Jewish symphony orchestra and sports clubs, such as "Maccabi Vilna." In 1924, the YIVO institute was founded to research Yiddish language and culture, which over time became the largest institute of its kind. Between the wars, Vilna was a modern Jewish cultural center that on one hand maintained ancient traditions and on the other burst with new and creative spiritual and cultural paths.

Upon the outbreak of World War II and the German and Russian invasion of Poland, Vilna was incorporated into Lithuania, and eventually became its capital. Despite fears and uncertainty about Lithuania's fate, many Jews flocked to Vilna from occupied Poland. By 1940, there were 14,000 refugees in the city. From among these refugee youth, there were two noticeable groups: members of Zionist youth groups and yeshiva students. In June 1940, Lithuania, with Vilna, was annexed to the Soviet Union, and became a Soviet republic. The Soviet authorities banned Jewish organizations and parties, and the Jewish educational and cultural institutions became government-run. The study of Hebrew, religion and Jewish history was forbidden. This nationalization greatly harmed the ability of many Jews to make a living. The Jews of Vilna, especially the refugees, looked for ways to escape to the free world, but faced many obstacles. Many countries closed their gates to refugees, and in wartime, it was virtually impossible to travel freely. In addition, the Soviet government objected to emigration from its territory, and attempts to do so were often considered acts of treason requiring severe punishment. The Soviets exiled thousands of refugees to the Soviet interior and Siberia. Despite this, thousands managed to leave Vilna and reach Eretz Israel, Russia and other places.

With the German invasion of Russia on June 22, 1941, Vilna suffered heavy shelling. A large number of Jews attempt to flee to the east, but the swift-moving German forces prevented this movement for many. By the time the Germans reached Vilna on June 24, 1941, less than 300 Jews had managed to escape eastward. Some 57,000-60,000 Jews remained in Vilna, a third of the city's overall population.

In the first months of the German occupation, the Nazis, with assistance from Lithuanian units, murdered 13,000 Vilna Jews in Ponary, a forested area ten kilometers from Vilna. On September 6, 1941, Vilna's Jews were expelled to two ghettos: the large ghetto, designated for professionals and workers; and the small ghetto, where the elderly, ill or jobless lived. Residents of the small ghetto were murdered in Ponary in the course of three aktionen in October 1941, thereby liquidating the ghetto. The murders continued over the next four months, until January 1942, during which time some 20,000 Jews were killed at Ponary.

From January 1942 until March 1943 the murders stopped. This was known as the "quiet period," and during this time social, cultural and spiritual activity flourished. The ghetto, led by the Judenrat, was productive, and most of its residents worked either inside or outside the ghetto. Judenrat policy, under the leadership of Jacob Gens, was based on the assumption that if the ghetto remained productive, the Germans would spare the ghetto from considerations of commerce and a ready labor force.

At the start of 1942, the FPO underground movement ("United Partisans Organization") was formed. In the ghetto's "quiet period," there was peaceful co-existence between the Judenrat and the underground, but in the spring of 1943, as ghetto conditions worsened and signs increased that its end was near, relations soured between Gens and the underground. Gens believed that bringing munitions into the ghetto and contacting partisans in the forests endangered the ghetto's existence. The first open conflict occurred when Gens attempted to remove the underground leaders by sending them to forced labor camps outside the city. In a different incident, Yitzhak Wittenberg, an underground leader, was compelled to turn himself into the Germans following their threat to liquidate the entire ghetto if their request was not met.

In August and September 1943, aktionen took place in the ghetto, during which more than 7,000 men and women fit to work were taken to a concentration camp in Estonia. During the expulsion aktionen at the start of September, the FPO called upon residents not to show up for deportation, but rather, start a rebellion. Ghetto residents did not heed this call because they believed – correctly, as it turned out – that the expulsion would be to a forced labor camp rather than to death at Ponary, as the FPO had claimed.

On the evening of September, a fight took place between German forces combing the ghetto and underground fighters. To prevent further skirmishes and out of fear that friction between the underground and the Germans would lead to the ghetto's liquidation, Gens promised to supply the Germans workers that could be sent to Estonia, according to the head count required, on the condition that the Germans removed their forces from the ghetto. The Germans acquiesced, and thus additional skirmishes within the ghetto were averted. Following the expulsions to Estonia, approximately 12,000 Jews remained in the ghetto.

On 14 September, Gens was summoned to the Gestapo, where he was murdered. On 23-24 Septebmer, the Vilna Ghetto was liquidated. Some 3,700 men and women were sent to concentration camps and more than 4,000 children, women, and elderly were sent to Sobibor, where they were murdered. Hundreds of elderly and ill Jews were taken to Ponary and murdered there. In Vilna, some 2,500 Jews remained at various work camps, and more than 1000 Jews hid within the empty ghetto, although a decisive majority were caught in subsequent months. A few hundred underground fighters took to the forest and fought as partisans.

At the start of July 1944, ten days before the liberation of Vilna, Jews from the city's work camps were taken to Ponary and killed. About 150-200 Jews managed to escape this liquidation and survived. On 13 July 1944, Vilna was liberated.

Less than five percent of the ghetto residents survived the Holocaust.