Archivo de Yad Vashem

Archivo fotográfico de Yad Vashem 1249/34

In the summer of 1942, with the beginning of the deportations of Jews from France, Holland and Belgium and increasing fears for the lives of Jews in the unoccupied zone of France, the number of those who crossed the Spanish border in the hope of saving themselves grew. Most were arrested by border guards and detained in regional prisons. In the autumn, the authorities began to consider their expulsion, having concluded that they were mostly Jewish refugees. The success of Operation Torch and the subsequent entry of German troops into Vichy France caused a mass emigration of young Frenchmen to Algeria across the border with Spain. Thus, the problem of Jewish refugees coincided with a primary concern for the Allies: avoiding the expulsion of the emigrants to France. Spain yielded to pressure to accept the refugees, on condition that someone would take care of their upkeep and prompt evacuation. The Jewish refugees were assisted by the Joint, which, being a Jewish institution, was prohibited from operating in Spain. It therefore had to operate through the representation of American aid organisations, under the auspices of the US embassy in Madrid. In Barcelona, it acted through the brothers Samuel and Joel Sequerra from Lisbon, who appeared as representatives of the Portuguese Red Cross. It is estimated that between the summer of 1942 and 1944, around 7,500 Jews from various countries entered Spain and were saved.

Spanish Jewish citizens in occupied countries

There were about 4,000 Jews of Spanish nationality in the countries occupied by Germany, and Spain had to avoid persecuting them as long as Spain recognized their status. Most of them were descendants of those expelled in 1492. In 1942, there were about 3,000 living in France and most of the rest in Greece. When the persecutions and expropriations of property began, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs instructed its representatives to assist them and protect their property, as if it were Spanish, but without exempting them from the general laws. These limited instructions meant that Spanish citizens had to depend on the initiative and attitude of diplomats. In January 1943, the Germans demanded that Spain evacuate its Jewish citizens within two months or leave them to their fate. From that moment on, Spain began to apply much stricter criteria regarding the rights of its citizens to be accepted into the country's territory and imposed the condition that they would have to leave for other destinations once they were allowed to enter its territory. It also adopted the criterion that a group of refugees would not be received until another group that had arrived earlier had left the country. These rules reduced the number of survivors who arrived in Spain to only about 800 souls.

Spain's participation in the rescue of Jews in Budapest

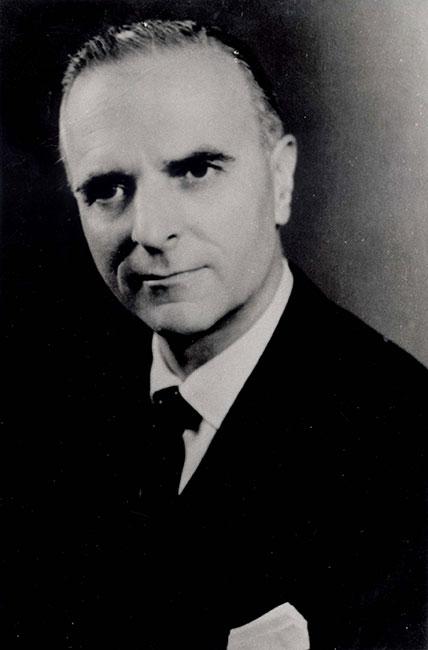

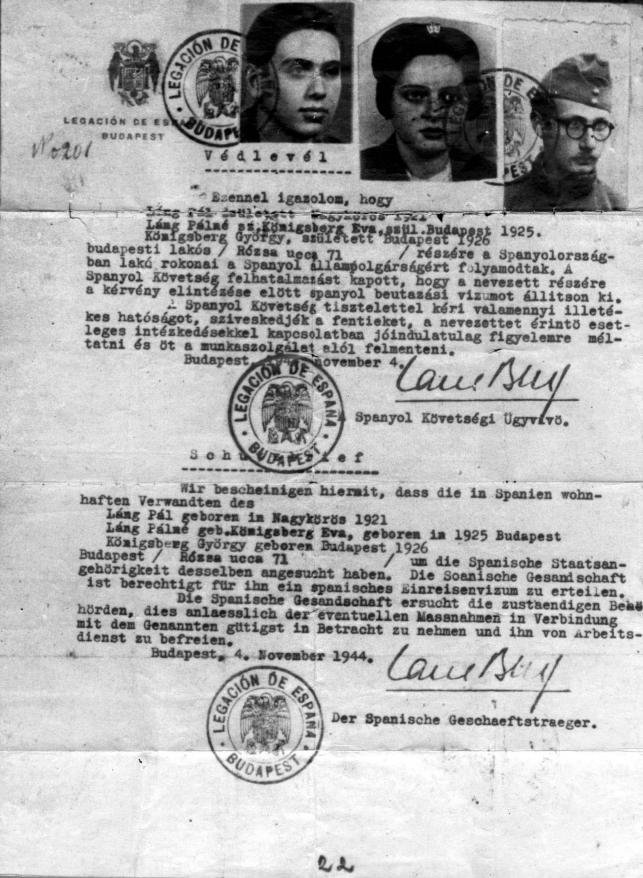

In the second half of 1944, in the face of German defeats on all fronts and Spanish concern for their future after the Allied victory, the chargé d'affaires in Budapest, Angel Sanz Briz, was authorized to participate in the initiative of the Vatican representative aimed at saving as many Jews as possible who still remained in Budapest, after the deportation of the rest of the Jews from Hungary. Around 2,250 Jews were saved thanks to various Spanish documents issued and by their concentration in houses placed under the protection of the Spanish government. After Sanz Briz was forced to leave Budapest in the face of the advance of the Soviet troops, the rescue was completed by Giorgio Perlasca, an Italian who had fought on Franco's side during the Civil War and was in the city on business. He posed as the Spanish chargé d'affaires and managed to retain and expand the rescue work. After the war and faced with the isolation to which the Franco regime was subjected, he began a propaganda campaign in which he claimed responsibility for the defense and salvation of all Sephardic Jews.

Summary

Despite hostility towards Jews in government and public circles during the war, and despite the regime's close ties to Nazi Germany, Jews who remained in Spain were not persecuted. Jewish refugees crossing the country to other destinations were not discriminated against, by ordinance or systematically, compared to other refugees. Also, when they crossed the Pyrenees illegally, they were not separated from other refugees in the same situation. The Spanish attitude towards saving Jews was revealed precisely in the indifference shown towards the absolute majority of the approximately 4,000 Jews who possessed Spanish nationality and who could have been saved from the clutches of Eichmann and his henchmen. Although these Jews were extremely close to Spain because of their language and culture, the authorities denied them the right to remain in the country, even when they decided to save some of them. In this case, the generosity and good nature of some Spanish representatives in the occupied countries stands out. Several of them deserved recognition as Righteous Among the Nations.