During the first years following Hitler’s rise to power, maintaining a religious lifestyle in Nazi Germany remained reasonably possible, both in the public sphere and in the home. Nevertheless, difficulties arose regarding issues such as keeping kosher, gathering a quorum and the like. With increasing legislation and control of the Jewish community, however, by the end of the 1930’s and early 40’s, any form of Jewish public life became extremely perilous. Likewise, with the Nazi invasion of other countries, community life in those areas became extremely difficult as did the public observance of traditional law which, in some places, almost completely disappeared. Only with this reality in mind can one evaluate religious life throughout the era of the Holocaust.

With the collapse of community life and undermining of the family structure, the religious lifestyle underwent a change. Those who persevered in keeping the traditional law attempted to maintain the few remaining expressions of the religious realm: kosher slaughter of animals, family purity, circumcision, keeping of the Sabbath, Torah study, keeping of annual religious holidays demanded devotion and resource.

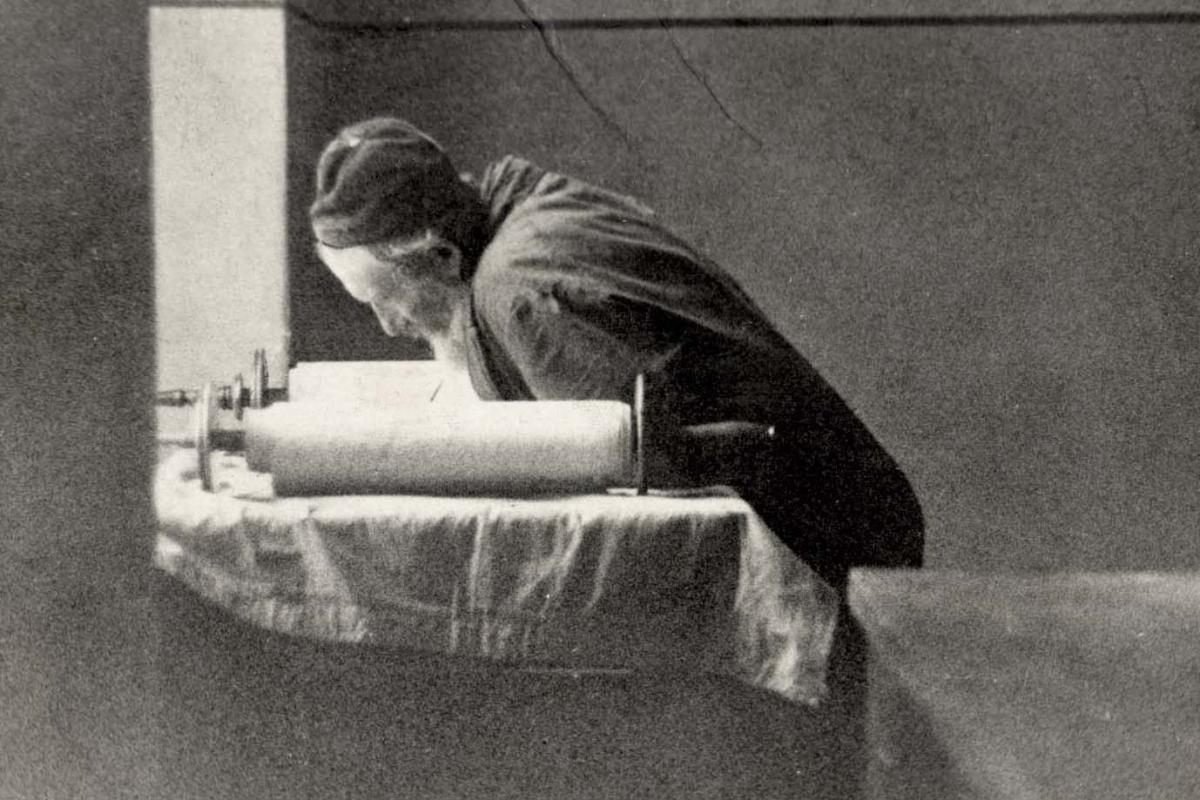

In some ghettos in Poland, for example, over a period of time public prayer was forbidden. Nevertheless, even then a quorum would continue to meet though in private homes. On festivals and on various other occasions, prayers were said with a large gathering even though assembling without permission was considered a crime, being absolutely forbidden. Harsh limitations were imposed in other aspects of religious life. In the Warsaw ghetto, for example, the kosher slaughter of animals was forbidden, even so, pious Jews found ways of smuggling kosher meat into the ghetto. Nonetheless, in lieu of the starving conditions, many Jews, among them religious traditionalists, expressed joy at any nourishment that reached their mouths without questioning its source. In some places, the Judenrate attempted to find ways to maintain religious activities with the approval of the rabbis.

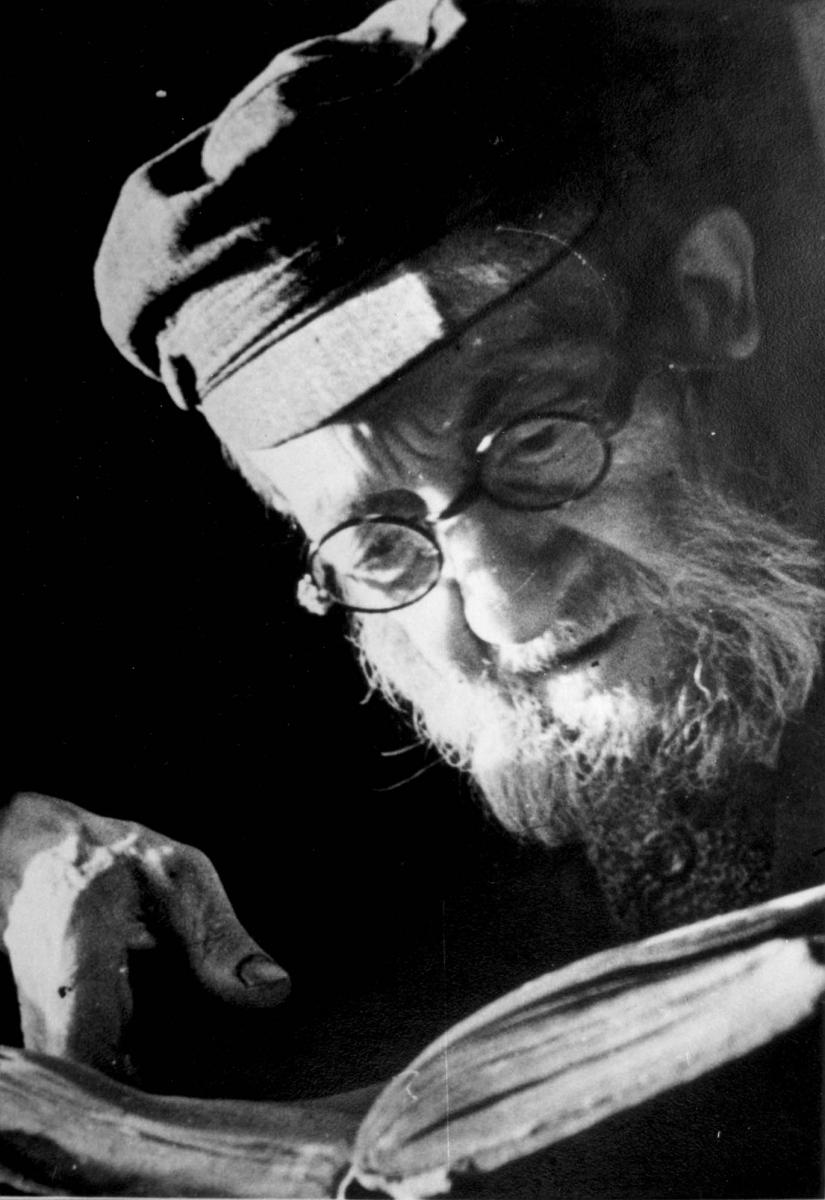

Rabbinic authorities on the Jewish Law attempted to cope with this unique situation of a religious person in war conditions. The rabbis declared the situation as life threatening, thus relinquishing adherents from many religious obligations. Take for example those, learned in the Torah who permitted the eating of non-kosher food or compelled the public to work on Jewish holidays in order to prevent the endangerment of lives under the command to “Thou shalt live by them” that they should not die. Nonetheless, there were those righteous individuals who acted in opposition to these rulings choosing rather to sacrifice their lives observing ‘to be heedful of a light precept as of a weighty one’. The majority of religious Jews attempted to observe those same laws that did not, by their observance, place them in mortal danger. As to their religious faith, there were those who, due to the difficult circumstances chose to halt their religious practices, remaining, however, true to their beliefs. Concurringly there was, in many instances, a weakening of faith, a direct defiance of religious institutions and religious personalities and even, in some cases, an outright declaration of profanity against God by those previously traditionally religious. Occasionally, in contrast, Jews from the secular bank would draw closer to their Jewish religious origins as a result of the difficulties.

As in all other spiritual activities, maintaining a religious lifestyle throughout the war, required great spiritual strength and in nearly every place there were Jews who persisted, at the risk of endangering themselves, to uphold Jewish precepts. Despite the compromise within the public sphere and that significant aspects of religious life had been severely damaged, many religious Jews continued to keep traditional law to the extent that conditions permitted.