Weddings in Ghettos and Camps

Jewish men and women continued to get married even after deportation to ghettos and camps, and under indescribable conditions. Alongside those couples who married for love, and entered into the marriage in order to have someone to share the hard times with, fictitious marriages were also held in the ghettos, in the full knowledge of the officiating rabbis. These were sometimes entered into in order to improve quality of life. Rabbi Huberband from Warsaw relates that many of these weddings took place at the point when people were forced into ghettos, in the hope of alleviating the cramped living conditions by sharing an apartment. Writers of the Chronicle of the Lodz Ghetto mentioned that married couples received additional food from the ghetto administration, as well as other gifts.

In other cases, weddings took place for the purposes of rescue. A man shielded from deportation due to being an essential worker or having preferential status in the ghetto, could provide the same protection for his wife, at least temporarily. In any event, marriages in this period offered much-needed companionship and partnership.

Weddings in the Lodz Ghetto

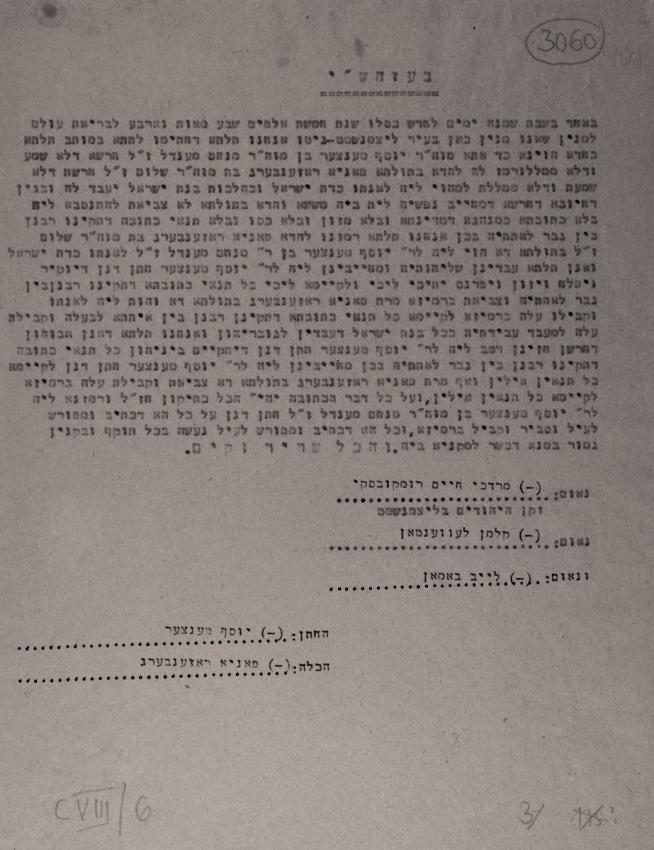

In the Lodz ghetto, a rabbinical committee operated under the auspices of the Judenrat's population registry office. The committee's responsibilities included coordinating marriages in the ghetto. The Germans disbanded the committee in September 1942, and from that time on, formal Jewish weddings were not held in the Lodz ghetto. In late October 1942, Judenrat chairman Mordechai Rumkowski started to officiate at the weddings himself.

Wedding ceremonies were usually held on Sundays, as these were days off work, and several couples would get married simultaneously.

Rumkowski granted himself the authority of religious legislator and reformer. He made changes to the marriage ceremony and even edited the traditional Ketubah (marriage contract) text as he saw fit, to suit the times. At Rumkowski's ceremonies, both partners signed the Ketubah and were asked separately if they were marrying of their own free will and not under duress. Sometimes, the bride and groom would exchange fountain pens in the absence of rings. At the conclusion of the ceremony, the couples and their witnesses would sign the registry office ledger in front of a clerk from the civilian registry department. Refreshments were sometimes served, and there would even be dancing.

From October 1942 until August 1943, Rumkowski officiated at 506 weddings.

After the war, rabbis questioned the Halachic (pertaining to Jewish law) validity of Rumkowski's weddings. After clarification and witness hearings, they ruled that the marriages were valid, but that the couples would have to reenact their wedding in accordance with Jewish law, including the seven traditional blessings and a new Ketubah.

Ruth and Majer Kalka

Ruth née Brzoska and Majer Kalka got married in the Czestochowa ghetto in January 1942. In the ghetto, rumor had it that the Germans were not separating married couples, and the Kalkas hoped that by getting married they would be able to stay together. After the wedding, the couple lived in one room together with another family in the ghetto.

A large-scale Aktion began in the Czestochowa ghetto on 22 September 1943 under the command of SS officer Paul Degenhart. In the course of the Aktion, which lasted until 7 October, Ruth and Majer's parents and other family members were deported to Treblinka, where they were murdered.

Ruth and Majer remained in the ghetto, but were separated in a subsequent Aktion. Slated for deportation to Treblinka, Ruth mustered her courage, took a wedding photograph out of her purse and showed it to Degenhart as proof of her married status. Degenhart signaled that she should join Majer's group, which was sent to the Hasag forced labor camp. The couple worked in munitions and arms factories. They succeeded in escaping the camp in March 1942 with the help of a Polish acquaintance, and spent the next two years moving from place to place, finding refuge with Polish families but living in perpetual fear of being caught.

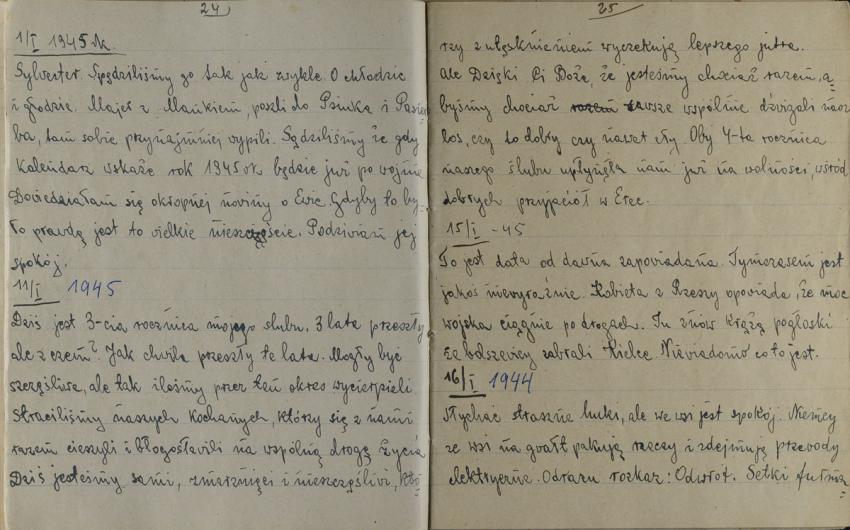

They marked their third anniversary in hiding. Ruth wrote in her diary:

"Today is my third wedding anniversary. How have three years already passed? It feels like an instant. These could have been happy years but we have gone through so much. We have lost our loved ones, who rejoiced with us at our wedding and gave us their blessing as we embarked on our new journey together. Today we are alone, freezing cold and sad, waiting for a better tomorrow… I hope that we will mark our fourth anniversary in freedom, amongst friends and in Eretz Israel [Mandatory Palestine]."

Majer and Ruth lived in hiding until the war's end, and immigrated to Israel in 1949. They have two children, Yaakov and Hadassah, who were born postwar. Majer and Ruth hid their wedding photographs in an iron box, which they retrieved after the war.

Yehoshua and Shoshana Halevy

In May 1940 a group of Beitar movement members under the leadership of Yehoshua Citron boarded the "Pentcho", a decommissioned tugboat, at Bratislava port in Slovakia, headed for Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine). Among its passengers were refugees from Germany who had been released from concentration camps.

For five months the tugboat sailed along the Danube, but the countries it passed on its way refused to provide the refugees with fuel and food. When the engine failed, the boat was propelled forward by the wind until it hit a rock. The passengers succeeded in reaching the island of Camilla Nisi. They inscribed the distress signal "SOS" on a large sheet, and sent five men out on a lifeboat to get help. An Italian reconnaissance plane spotted them and sent an Italian boat from Rhodes.

The Italians detained the passengers in Rhodes, and then sent them to the Ferramonti di Tarsia detention camp in Italy.

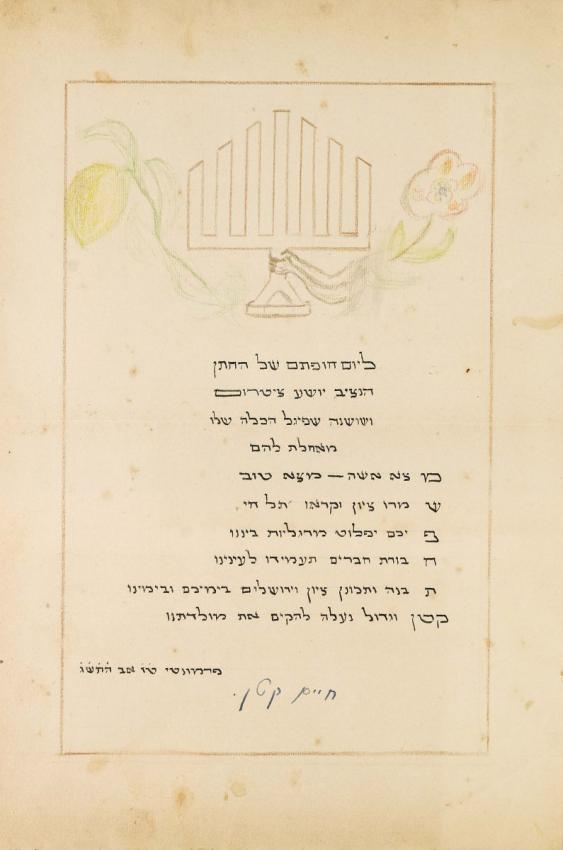

On 17 August 1943, three years after they set out on their journey, Yehoshua Citron and Shoshana Spiegel got married in the camp. Shoshana was the secretary of the Beitar movement, and she had worked together with Yehoshua in Slovakia. Good friends from the movement whom the couple knew from Slovakia were present at the wedding. Their Beitar friends prepared an album of written and illustrated dedications as a wedding gift, in which they expressed their hope that the couple would be able to reach Eretz Israel and to build their home there.

The camp inmates were liberated when the Allies conquered southern Italy in 1943. The passengers of the "Pentcho" reached Eretz Israel in 1944.

Shoshana and Yehoshua started off in a detention camp in Atlit, and then moved to Netanya. They changed their family name from Citron to Halevy. Yehoshua joined the Irgun (Etzel) and was active in the Herut movement. They have two children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Gise and Moshe Rachmot

Gise (Gisle) Wahl was born in 1922 in the city of Rădăuți, Romania. In October 1941 she was deported to Transnistria in Western Ukraine, together with her parents, two brothers and thousands of Jews from Bukovina and Bessarabia. Moshe Rachmot, born in 1912, was also deported from Rădăuți together with his parents and two of his siblings. Both families found themselves in Mogilev-Podolski.

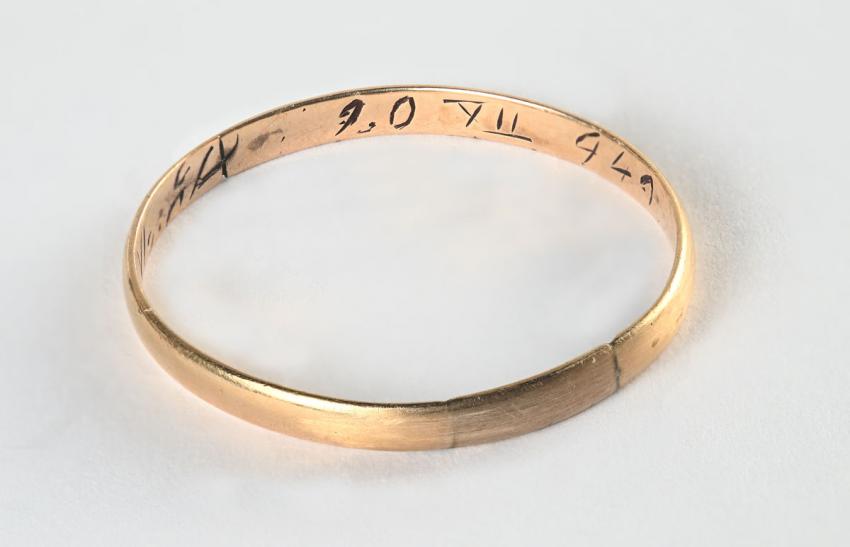

Moshe and Gise already knew each other from Rădăuți, and got married in July 1942 in the family's apartment in Mogilev-Podolski. On the same occasion, Mina, a relative and close friend of Gise's married her partner, David Ramert. A rabbi officiated at the double wedding, and after the ceremony, there was a party. The wedding ring that Moshe gave Gise is engraved with the couple's initials and the wedding date – 20 July 1942.

Moshe and Gise rented a room from a Ukrainian in Mogilev-Podolski, and Moshe practiced medicine. He treated Jews and locals, most of whom paid him with food, which helped the Rachmots and their extended family to survive.

The Red Army reached Mogilev-Podolski on 19 March 1944, and the Rachmots returned to Rădăuți, where they lived together with Moshe's parents, Shimon and Malka. In 1950, their son Herman was born, named after Gise's father, who had succumbed to typhus during the war.

The family immigrated to Israel in 1959 and settled in Bnei Brak. Gise kept her wedding ring until she passed away in 2010.

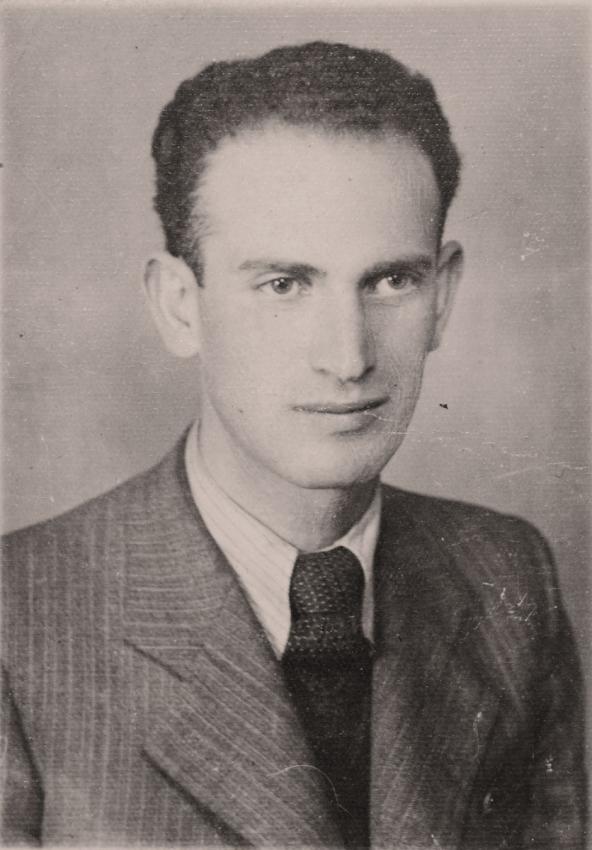

Peretz and Natalia Chorshati

Peretz Chorshati was born Pawel Schoenwald in Warsaw in 1920. In 1940, he was incarcerated in the Warsaw ghetto together with his family. Approximately one year later he was transferred to the Nedev labor camp, where he was put to work constructing an underwater bridge, but he escaped and returned to the ghetto. During the period of the Great Deportation from the Warsaw ghetto in the summer of 1942, Peretz evaded deportation thanks to the essential worker permit that his father obtained for him.

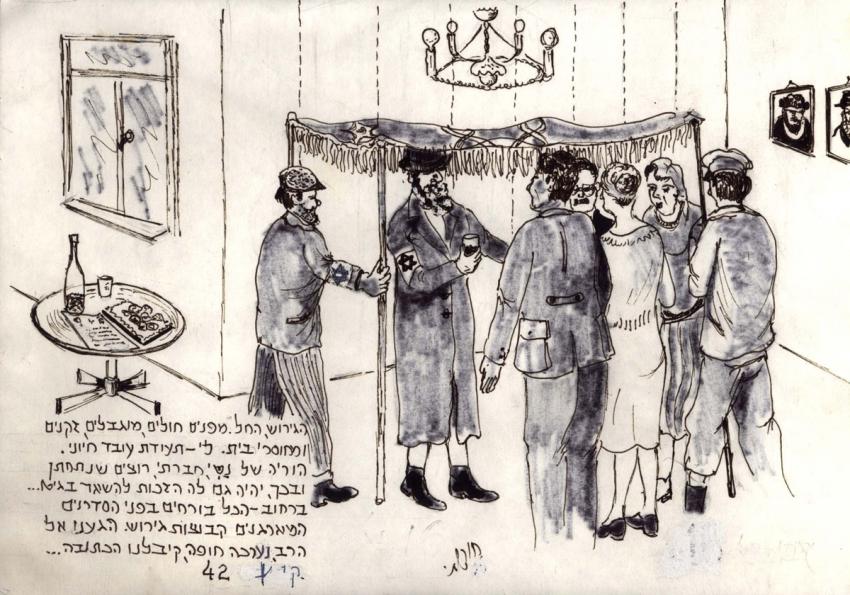

At that time, there was a proliferation of fictitious marriages in the ghetto: many women sought to marry men with documents that would protect them and their families. A Jew attempting to save his daughter, Natalia, approached Peretz with the request that he marry her, and he agreed. Peretz and Natalia made their way stealthily to the rabbi's house, where the wedding ceremony was performed while a manhunt was taking place in the ghetto.

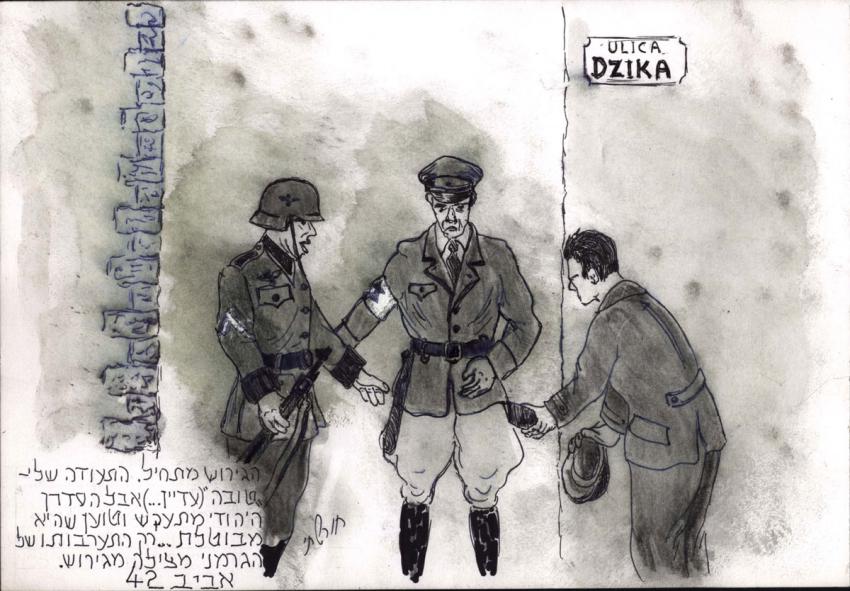

The married couple lived together in the ghetto for two weeks, fleeing from place to place and hiding in empty houses so as not to get caught. After that, Peretz posed as a Pole in order to leave the ghetto and work as an electrician. When he returned, Natalia had vanished, and he was told that she had been seized by the Germans.

Peretz used forged papers to leave and reenter the ghetto. He was eventually caught, but succeeded in escaping and reached the Lida ghetto, some 490 km east of Warsaw. He joined Tuvia Bielski's partisan unit in the Naliboki forest, approximately 100 km east of Lida, and fought in the ranks of the partisans until the Red Army's arrival in the area.

Peretz immigrated to Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine) in 1946. He joined the Irgun (Etzel), and after the establishment of the State, he enlisted in the Israel Defense Forces. He was one of the builders of the fire station in Eilat, and managed the station between the years 1964 and 1980.

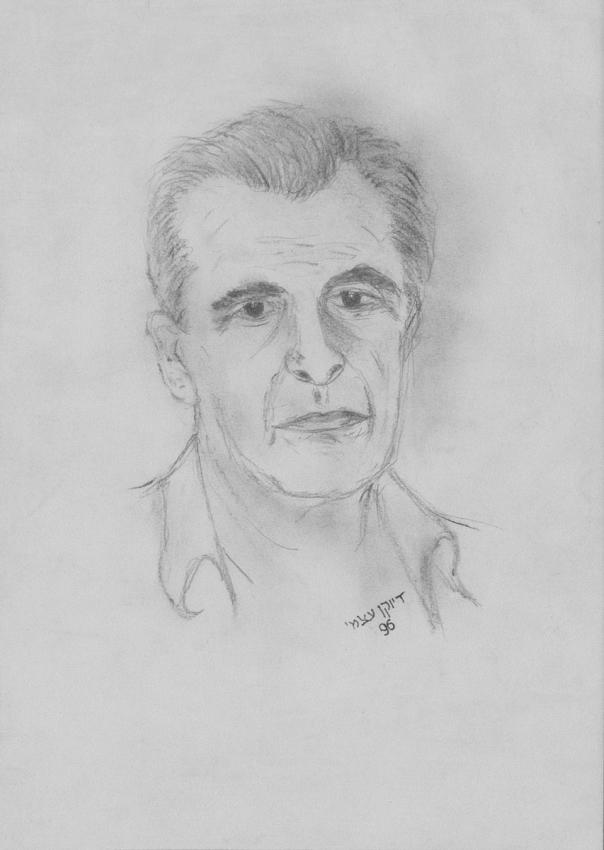

Peretz started to draw at the age of 75. In a series of over 200 artworks with textual accompaniment, he documented what he had seen and experienced in his lifetime: his life in the Warsaw ghetto, his marriage to Natalia, his escape and recruitment to the Bielski brothers' camp.

Seventy years later, Peretz discovered that Natalia had actually survived the war and also lived in Israel. They renewed their friendship until Natalia's death, a short time afterwards.