Oskar Schindler’s deeds during the Holocaust period have received considerable coverage, mainly since the release of the film “Schindler’s List” in 1993. There is much original documentation about the man and his activities, such as material about the concentration/labor camp Plaszow, where most of the people he saved were inmates.

In the course of his research on the Jews of Krakow, Mr. Yair Shor discovered as part of his research on the Plaszow concentration camp, extraordinary photographic testimony supporting the Schindler story in the US National Archives.

15AO4

From the private collection of Amon Goeth

The Plaszow camp was set up in the fall of 1942 as a forced labor camp for the Jews of neighboring Krakow.

It was run by the local SS headquarters, but until its transformation into an official SS concentration camp on 11 January 1944, most of its guards were Ukrainians. The camp was gradually expanded over the years of its operation; it included SS barracks, various factories, and separate camps for the men and women.

Poles were also imprisoned in the camp, but from July 1943, they were kept separate from the Jews. It is estimated that approximately 150,000 people in all were inmates in the camp, the majority being Jews1. About 8000 prisoners were killed. At the peak of the camp’s activity – from February 1943 until September 1944 – Plaszow was under the command of SS officer Amon Goeth.

Following its transformation into a concentration camp, Hungarian and Slovak Jews were brought there too. From May 1944, traffic in and out of the camp increased greatly as Plaszow served as a transit camp for Jews on the way to Auschwitz and other camps. Prisoners only stopped arriving in the fall of 1944, when evacuation of the camp commenced2. In September 1944, as part of the operation to downsize and eventually dismantle the camp, a special SS unit opened up the mass graves on site and burned the bodies, thereby erasing all evidence of the atrocities committed3.

The last remaining Jews were sent from Plaszow to Auschwitz on 17 January 1945, just three days before the Red Army reached Krakow.

The Germans forced Plaszow inmates to work in a large number of factories, both within and outside the camp. Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist and businessman, owned an enamel factory in the Zablocie industrial zone, in the south of Krakow, and employed Jews from the ghetto to work there until the ghetto’s liquidation in mid 1943.

After that, he turned his factory into a sub-camp of Plaszow, and in this way, was able to save about 900 Jews from the camp. There are many photographs from Plaszow, the majority of which were taken by the SS men stationed there. The camp commandant, Amon Goeth, took many photographs, some of which can be found in the Yad Vashem Archives. In addition, we now know that a special photo-reconnaissance unit from the German Air Force photographed both Krakow and the camp at least twice: on 3 May 1944 and 28 December 1944. These photographs were originally taken for mapping purposes, but they later assumed a different significance.

The photographs taken in May are particularly interesting, as they depict Plaszow at the height of its activity as a concentration camp. One of the photographs clearly shows all the details of the camp.

The gate, Appelplatz and prisoners’ barracks are all easily identifiable, as is Amon Goeth’s villa, from the balcony of which he would shoot at inmates working inside the camp, as portrayed in “Schindler’s List”. Also visible are the cable factory next to the camp’s entrance, and the quarry to its north. After the camp was set up, this quarry was built on the grounds of the old Jewish cemetery in Podgorze, the gravestones of which were broken up and used as paving stones inside the camp4. A large percentage of the camp inmates were made to work in the quarry, which was also used for executions, mostly by shooting5. As aforementioned, this period saw the commencement of the deportation of the camp’s Jewish prisoners, and so, as opposed to later photographs, it is not yet possible to see any signs here of downsizing the camp or dismantling its structures.

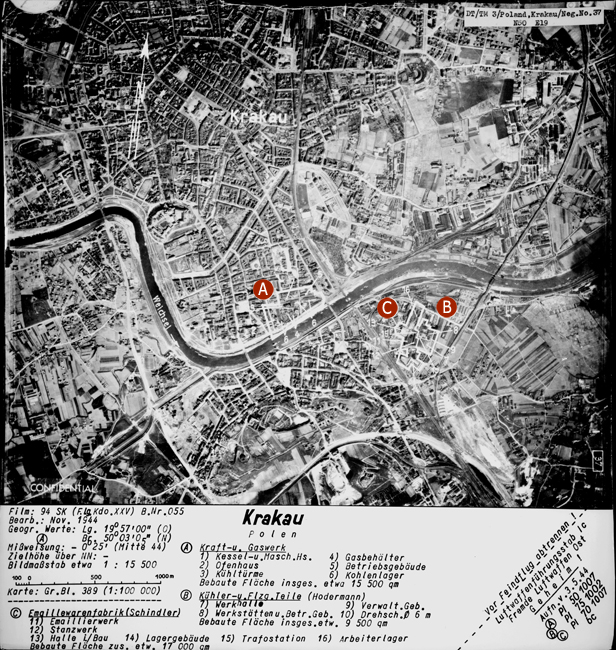

About three months after the photographs were taken, and probably as a result of the Red Army’s progress, these photographs were pulled from the Archives and re-examined. The Germans marked a number of potential targets for attack, should the area fall into Soviet hands. One of the targets marked on the photographs was Oskar Schindler’s famous factory. The factory was marked with the letter C, and the photo interpreter identified its different components, including the main workshop and what was called the “workers’ camp”.

One of the advantages of aerial photographs is the fact that unlike maps they are multi-dimensional, allowing a live view of different geographic elements, the relationship between them and the features of the area. This is clearly shown in a photograph taken later in 1944.

This photograph clearly shows the geographical relationship between Krakow, the ghetto (which had already been liquidated in March 1943), Schindler’s factory and the Plaszow camp. It reflects the geographic logic behind the Germans’ treatment of the Jews of Krakow6. As a first stage, in 1941 they were concentrated in the Jewish quarter, Kazimierz, and then transferred over the river Vistula to the relatively isolated neighborhood of Podgorze, where the ghetto was established.

In the course of the evacuation, they had to cross over the tram bridge, which also appears in photographs taken from the ground during the deportation.

Some of the ghetto’s Jews were taken for forced labor in nearby factories. We can see from the photograph that the neighborhood of Podgorze was well suited for the task of exploiting the Jews economically.

South of Podgorze was a large quarry, and to its east, the industrial area of Zablocie, where Schindler’s enamel factory and an aircraft parts factory were located, amongst others. In the course of the liquidation of the ghetto in March 1943, the Germans transferred to Plaszow those ghetto inmates who were neither murdered nor deported to Auschwitz. As the photograph shows, this transfer too was logical from the standpoint of exploiting the Jews. The camp was very close to the ghetto, the industrial zone and the quarry.

The ghetto and camp complex also made sense for the logistics of murder: both were located very close to the main railway line. The ghetto was adjacent to the Zablocie railway station, and the camp was very close to the Plaszow railway station. The left fork in the tracks leaving Plaszow station led directly to Auschwitz7.

In the last photograph – probably taken in November or December 1944 – the dismantling of the camp is already clearly visible. We can see that at this point, at least 22 buildings inside the camp had been torn down – buildings that were still standing in May. At the same time, the number of prisoners in the camp was apparently reduced greatly in preparation for the final evacuation in January 1945.

The aerial photographs of Krakow/Plaszow were discovered thanks to the efforts of Mr.Yair Shor whose grandparents Meir and Miriam Shor from Krakow were murdered in Plaszow on 8 August 1943. We hope that further aerial documentation related to the Holocaust will be discovered in the future.

- 1. Duda, Eugeniusz, The Jews of Cracow, Krakow, n.d., p. 71.

- 2. Yad Vashem, Pinkas Hakehillot: Poland, Vol. 3, Jerusalem, 1984, p. 41.

- 3. Yad Vashem Archives, testimony of Ewa Jakubowicz, M.49E/3229.

- 4. Yad Vashem Archives, testimony of Lejb Szternfeld, M. 49E/3326. The camp itself was built on the site of Krakow's new Jewish cemetery.

- 5. For example, the murder of approx. 40 Jews on 16 March, 1943. Yad Vashem Archives, testimony of Figa Berek, M. 49E/3232.

- 6. For more information about the route used by the Jews of Krakow and depicted in the movie Schindler’s List see: Samsonowska, Krystyna, Schindler’s List: A Guidebook, Krakow, 1997.

- 7. As clearly shown in the railway map of the German District Employment Ministry. Dr. Scholl, Die Struktur des Arbeitsamtesbezierkes Krakau, 1942, map 5.