May 1945, the end of the war. In a monastery in the town of Žilina in Slovakia, an eight-year-old Jewish boy called Juri Breznitz waited for his parents Janka and Josef to come and collect him. Juri knew that his parents had been sent to Auschwitz and he feared that he wouldn't recognize them. He also worried that they wouldn't recognize him, tanned and disheveled, as "the clean, well-brought up boy" that they had left at the convent, and more than anything he worried that they would never come.

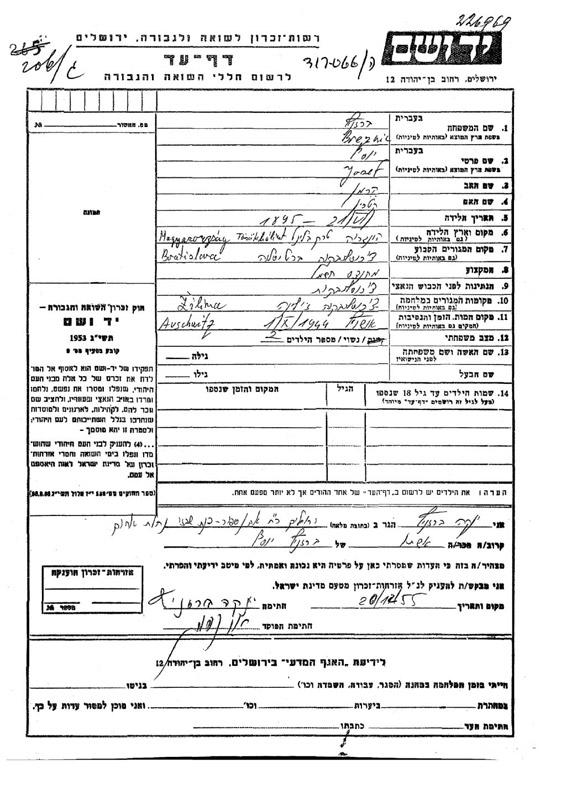

Shlomo (Juri) Breznitz was born in Bratislava, Slovakia in 1936. In 1942 he was sent, together with his mother and sister, to a camp in the city of Žilina in North-West Slovakia. This camp, located near the central train terminal, served as a major center for deportations to Auschwitz. For some time, his father's position as chief engineer of the Transylvanian electrical company provided him with a degree of immunity and he was able to prevent his wife and children from being sent to Auschwitz. The family wandered between a number of locations.

In the ignorance of childhood, I had only a remote sense of the world that was crumbling around us. Although this, our third home, lacked many of the comforts I had always taken for granted, we did not suffer… But the worry and the sadness that descended on him (Father) and Anyuka (Mother) were too obvious to ignore. By this time the rest of the family had been lost, and sooner or later the Slovak guards would find us and take us away as well.

Shlomo Breznitz, Memory Fields, Knopf, 1993 p25

In 1944, with the collapse of the Slovak uprising and the occupation of Slovakia by Germany, his father lost his immunity against being deported. The night before their deportation to Auschwitz, the parents placed their children Judith and Shlomo in an orphanage run by the sisters of the Saint Vincent's Convent in Žilina, in a final attempt to save their lives.

Loneliness, hunger, constant longing for their parents, dealing with repeated harassment from the children in the orphanage and the constant fear that their identities would be discovered were young Shlomo's daily fare in the convent. His phenomenal memory was discovered during his time in the convent and it helped him to recite the Christian prayers by heart. This ability earned him the protection of the local bishop who thought that the boy would fulfill the fable of the Jewish orphan who would one day become the Pope.

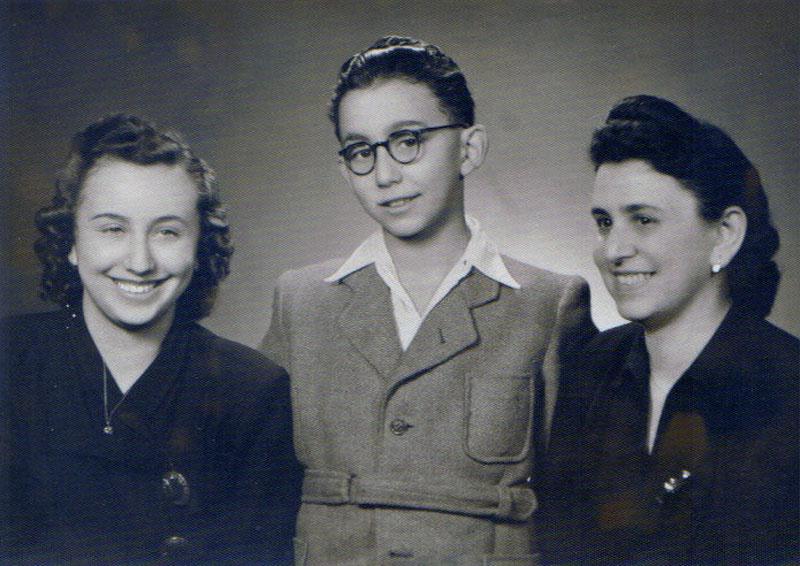

Shlomo's father was murdered in Auschwitz. His mother Janka survived and returned after the war to collect her children from the orphanage. The nuns gave her Judith but at first refused to return Shlomo – the "wonder child" of the convent destined to fill the highest position in the Catholic Church. Shlomo was only returned to his mother following the involvement of the authorities. In 1949 Shlomo immigrated to Israel together with his mother and sister.

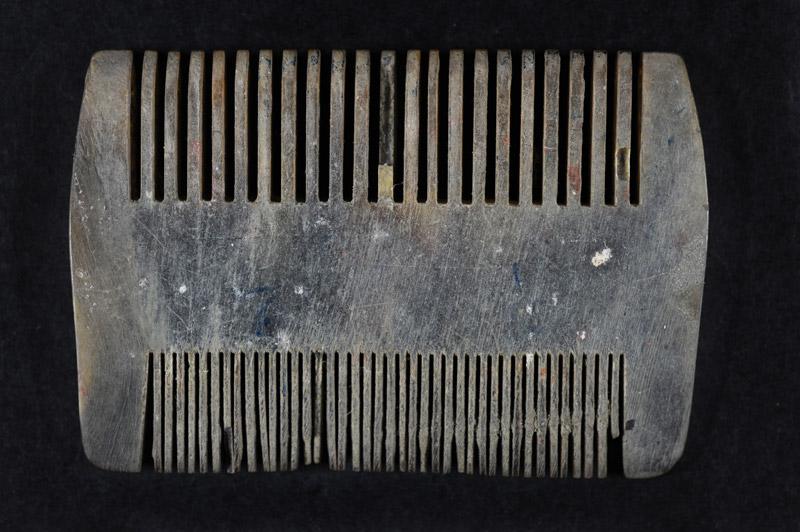

When mother died, with the exception of a few photographs I did not care to keep any of her material possessions. However, there is one small item that Judith and I cherish above everything else. It is the dirty and broken comb that she brought back from Auschwitz. She traded it for a full day's ration of bread in order to have a chance to comb her closely cropped head.

Shlomo Breznitz, Memory Fields, Knopf, 1993 p165

The comb was the only item Shlomo owned that had belonged to his mother in the war period. He gave the comb to Yad Vashem to preserve for posterity.