Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

A young woman with a sad expression leans her head against a tombstone bearing the inscription:

Our mother, Mrs. Chava Sheindel, wife of Rabbi Meir Eilenberg… Her soul ascended to the heavens at age forty-six on the 23rd of the month of Kislev 5683.

The young woman in the photo is Miriam (Mania), the third of Chava and Meir’s ten children; they lived in the town of Ciechocinek in the Warsaw district of Poland. Ciechocinek was a spa town that was known for the therapeutic properties of its saltwater springs. Then, as now, many people would come to the town in search of a cure for their ills. The local Jews’ income was partially based upon providing services to these visitors. The Eilenberg family rented out an estate that Meir had inherited from his father Ephraim; they lived in a wooden house on the estate grounds.

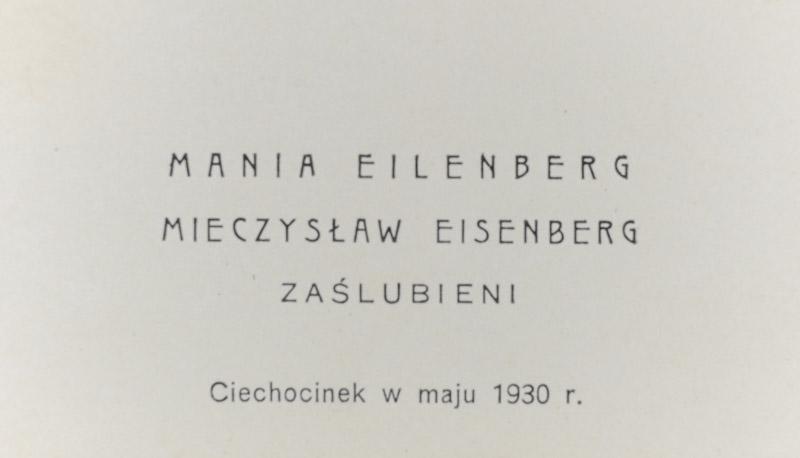

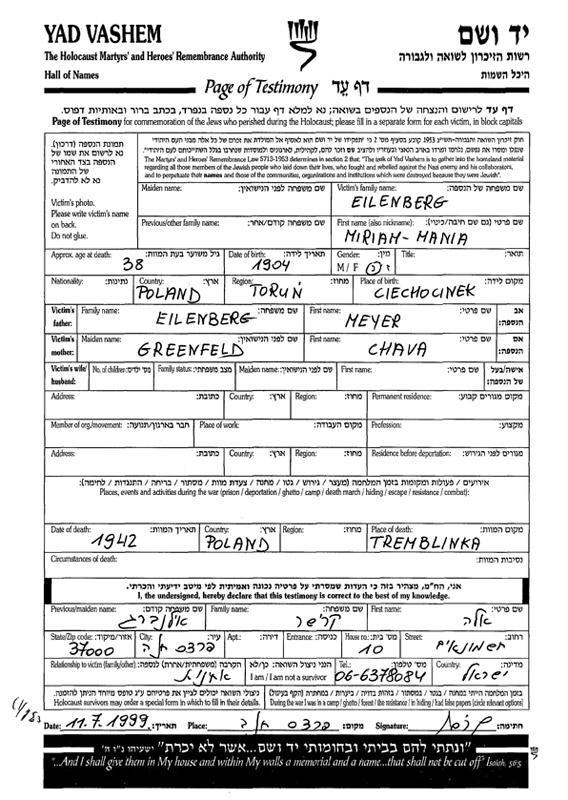

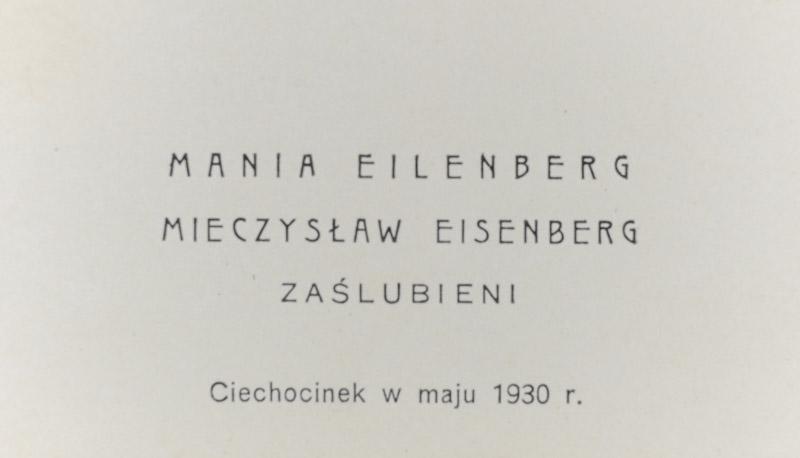

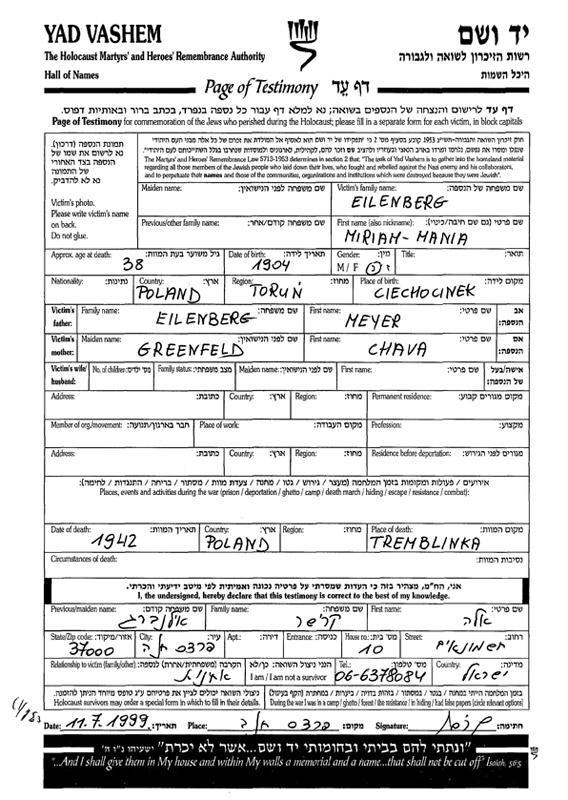

Miriam was eighteen years old when her mother died in 1922. In 1930 she married Mendel Mieczyslaw Eisenberg. The couple continued to live in the town, and a year later their son Benjamin was born.

Miriam didn’t have a much longer life than her mother. At the end of October 1939, after their property had been stolen, the Germans deported the majority of the Jews of Ciechocinek to towns in the Generalgouvernement in Poland. From there, they were later deported to the death camps. Miriam and Mendel Eisenberg and their son Benjamin were murdered in Treblinka in 1942.

Three of the ten Eilenberg children survived. The only one who did not experience the horrors of the Holocaust was Shoshana, the second daughter, who had immigrated to Eretz Israel in 1924. Two of the younger boys joined the many Jews who fled eastward at the outbreak of the war, and survived. Haim Leib, the eighth son, fled to Mir where he married Eugenia . On hearing rumours about an impending Aktion he, his wife and her family fled from the Mir ghetto to the forest. Eugenia’s family later returned to the ghetto and was murdered there. Chaim and Eugenia stayed in the forest and joined the Bielski family camp in the Naboliki Forest. In September 1943, Eugenia gave birth to their eldest son Jolka under a tree in the forest.

The ninth son, Aron, fled to Russia, eventually reaching Uzbekistan where he stayed until the end of the war.

The two brothers returned to Poland after the liberation. Chaim and Eugenia’s daughter Ela was born in Poland after the liberation; she immigrated to Israel in 1967. Her parents followed her a year later. Aaron immigrated to the United States with his wife Cipora and their two children, Mark and Sarah.

On 6 October 2004, during the holiday of Succot (Tabernacles), an article by Yehuda Yaari was published in the Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot, about a roots trip that he had taken to the town of Ciechocinek together with his mother and brother.

Ela identified her father in a photograph that was published alongside the article. Ela recalls, "I was reading an article about a small town, and suddenly I identified my father in the small photograph – it was very exciting."

The article describes a meeting between Yehuda and his family and the man who had been identified as the last Jew living in Ciechocinek – Adam. Adam told them that a number of years earlier his neighbors had redecorated their apartment, and one of the workers had come to him with a bag full of books and photographs that they had found while renovating. They offered to sell them to him as he was the last Jew living in the town. Adam bought the items and sought to return them to their owners. He approached the Yaari family, assuming that they were the owners of the items.

"Close the door," he gestured. He put the black sack on the sofa, opened it and took out a parcel of old, decayed photographs. From beneath the photographs he took out some crumbling prayer books… the further we looked, the more times we came across the name ‘Eilenberg’. There was a New Year card that Miriam Eilenberg received before Rosh Hashana in 1924, photos of graduates of the 6th grade class of 1932, a boy being held by his mother, a loving couple in the garden, two friends dressed up… We knew the name Eilenberg, it appeared on the maps that had been drawn for us before we travelled, but we had no way of identifying anyone in the photographs. We had come here to search for traces of the Zelczinski family. (From the article)

Following up on the article, Ela contacted Adam. When he understood that descendants of the owners of the items had been found, Adam sent Ela her family’s photographs and documents.

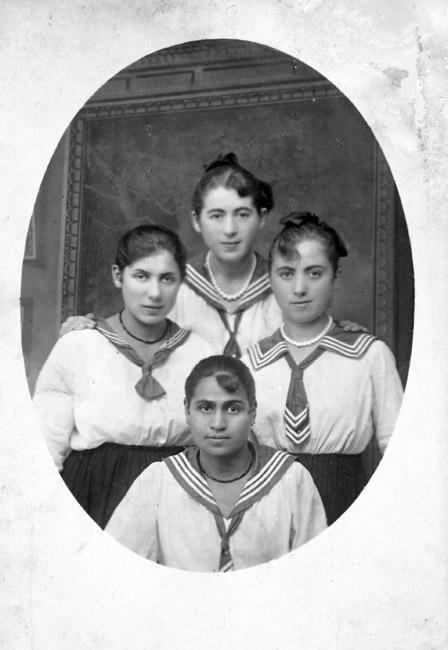

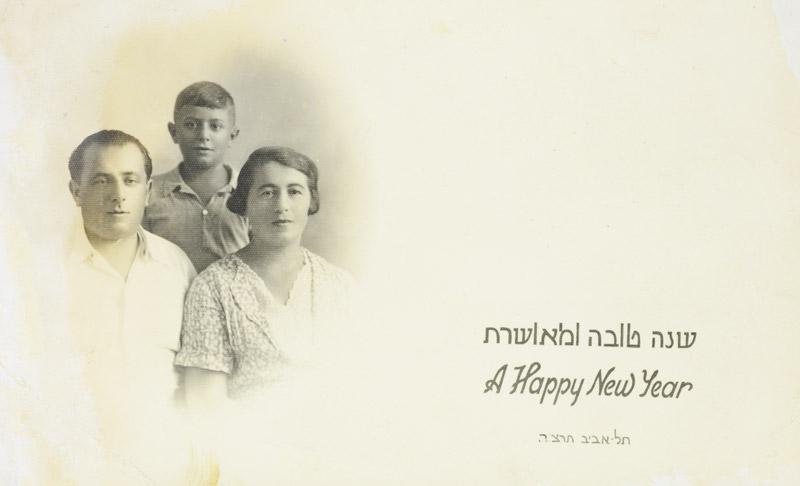

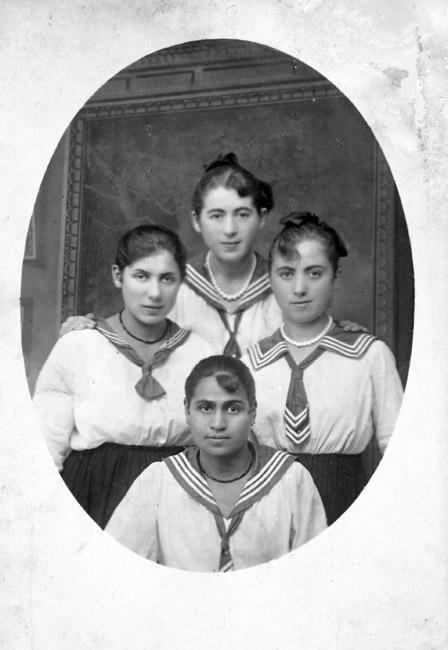

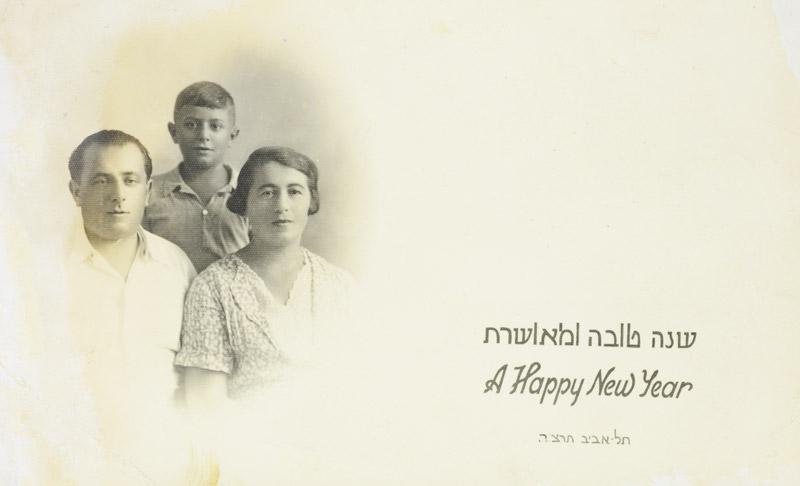

Thus, sixty years later, Ela was finally able to put faces to the names and stories she’d heard about Chava, Meir and their ten children - the grandparents, uncles and aunts that she had never known. Among the photographs she found a photo of her aunts – Rosa (Shoshana), Ludka, Rina and Mania. Another portrays her aunt Miriam, smiling out from her wedding photograph, and others depict Miriam and Mendel’s son Benjamin – as a baby looking out from his pram and later, wrapped up in a coat and sitting on a sled alongside his parents. In another photograph a two-year-old is playing with some dolls - Harry (Shaul) Lang, the son of Rosa and Shmuel Lang, who was born in Eretz Israel. The family in Ciechocinek who had never met the first member of their family to be born in Eretz Israel knew him only though the photos that Rosa sent her parents. On the back of a postcard sent from Tel Aviv in 1935, Harry smiles out from between his parents, and next to the photograph is the Hebrew greeting, “Happy New Year.”

Among the documents found in the sack was an envelope with spare invitations for Miriam and Mieczyslaw-Mendel’s wedding. It seems likely that the sack was found in the couple’s former home.

When Adam visited Israel with a delegation from Poland, he brought with him the religious books that had been in the sack.

The books, among them a Passover Haggadah and a prayer book for the High Holy Days had belonged to Ela’s grandfather, Meir Eilenberg.

Ela and her cousin Arnon, Shaul’s son, came to Yad Vashem after hearing about the “Gathering the Fragments” campaign. They donated the photographs, the postcards and the documents that had been in the sack to Yad Vashem for posterity. The family had already donated the Jewish books to Yad Vashem several years earlier.

Regarding the decision to part from the photos that she had received as a distant memento of her family members who had perished in the Holocaust, and to donate them to Yad Vashem, Ela said, "I agonized over whether or not to donate the photos, but it was important to me to preserve the memory of the family members who had perished. When I left Yad Vashem I was relieved – I knew that from now on they will be kept in a good place and the family will not be forgotten. I had closure."

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue