We write to you regularly but we don’t know if you have been receiving our letters. It’s very cold here. We hope that you received the parcel we sent you…

Write to me about your work and tell me how I can help you.

I’m really sorry that I never taught you how to make good honey.

I’m amazed that there are Jews who don’t like agricultural work.

Kisses,

Father.

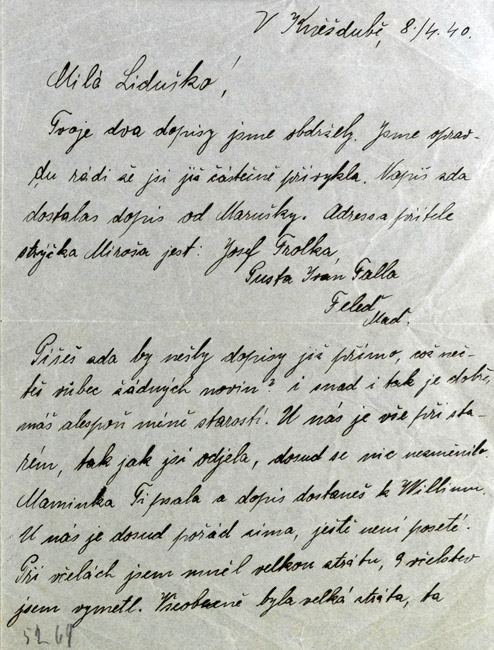

These words were written on 31 September, 1940 in Czechoslovakia by Maks Felsenberg to his eldest daughter Lida, who had immigrated to Eretz Israel a few months earlier. In his letter, Maks, an experienced farmer, expresses concern about his daughter’s welfare in Eretz Israel, where she had started working in agriculture at a pioneer women’s farm near Afula.

This letter is one of many that Lida received from her family during the years 1940-1942. The letters express the family’s extreme longing for their daughter, who was so far away.

In an earlier letter, sent not long after Lida moved to Eretz Israel in 1939, her father wrote:

3/1/1940

I’m pleased that you have made friends, and that some of them are Czech.

We are always with you, and you are always in our thoughts.

Be careful, and don’t assume that all people are nice; keep your eyes open.

Please write to us frequently and at length.

Everyone in the village is asking after you…

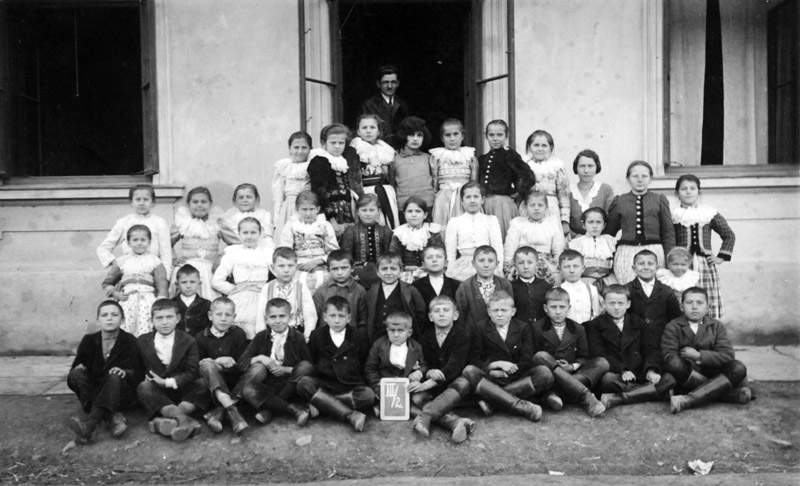

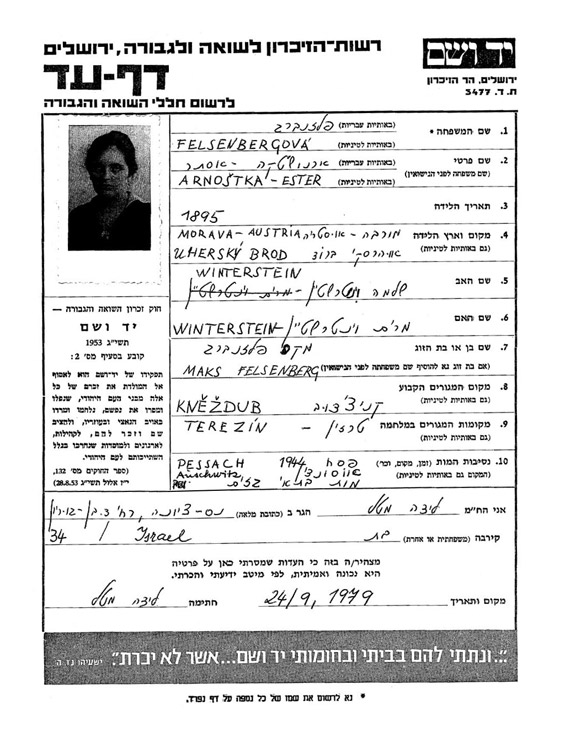

The village that Lida had left was the small Moravian village of Kněždub. The Felsenbergs were the only Jewish family in the village. Maks, the head of the family, had been born there and was the only one of his ten siblings to stay and make his home in the village. He married Ester née Winterstein and they had three daughters – Lida, Anda and Susannke. The Felsenberg family was a prominent family in the village. Maks owned the village grocery store and was also a well-known farmer. The girls were very involved in village life and this can be seen by the interest, evident in many of the letters, that the villagers showed in news of Lida after she had left.

In March 1939 Germany invaded Czechoslovakia, and people feared for their future. Lida, who was a member of the Maccabi Hatzair youth movement, was sent for pioneer training by the movement, and immigrated to Eretz Israel in 1939.

You see – I’m writing to you in Czech. I have to learn the language now.

Anda has gone for pioneer training, you are in Eretz Israel. Now, only Susannke is at home with us.

We have a lot of work, which is good for me, because it doesn’t leave me time to think about the future…

(Ester’s letter to her daughter, dated 31 January 1940.)

Anda, who had begun pioneer training in the meantime, wrote to Lida on 13 January 1940:

I don’t know what you are going through in the new country.

I’m here, in a very pleasant place in the camp.

I hope that the people here in the camp will love one another as we do.

Are you receiving all the letters from home?

Please don’t be sad.

We - many people here - are thinking about you and are hoping to reach the country where you are now.

I give you my hand and all that I wish for you,

Anda.

Anda’s hopes to join her sister in Eretz Israel are expressed repeatedly, but the letters reflect her growing fear that it will never happen:

1/2/1940

I don’t know when I’m leaving. It may be very bad at the end of April. Something terrible is approaching…

Lidonka, I wish you the very best on your birthday, with lots of love and I hope to see you soon.

I hope that you don’t feel sad - we are always with you.

We hope that we will all be reunited in Eretz Israel.

My hand is squeezing yours. Be happy.

Yours,

Anda

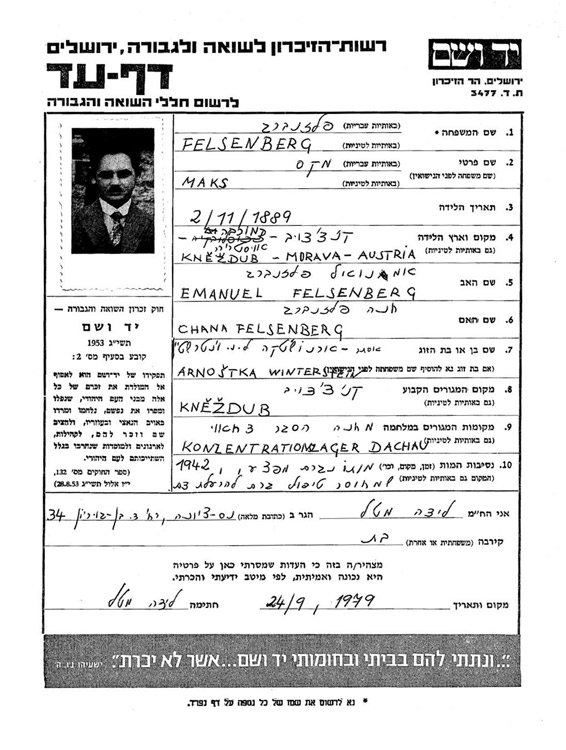

Towards the end of 1940, Maks was sent to the Dachau concentration camp.

In this letter that he sent his family in the village on 8 December 1940, the conditions under which he and the other camp inmates were being held are apparent between the lines.

I want to tell you that I am healthy and feel well.

Please write to me and tell me how you are, if you are healthy and what you are doing.

You can send me one letter every three months.

Pay attention to all the instructions, you are allowed to send money.

Andolka, I wish you all the best on your birthday.

You too Susannke, I send you all best wishes because I won’t be able to write to you again in time.

Please forgive me for my poor handwriting – this is the best I can do without my glasses.

I’m sure that you have taken care of the bees, and that you have reaped and sown. Please write to me and tell me everything in detail.

Don’t close the shop!

I don’t have anything more to write.

I bless you and send you kisses.

Your husband and father, Maks.

Please send my regards to everyone.

Maks perished in 1942, apparently from blood poisoning resulting from an untreated leg wound. Only two of his ten siblings survived.

Ester, Anda and Susannke were deported to Theresienstadt. They were later sent on one of the last transports to Auschwitz, where they were murdered in the gas chambers on Passover in April 1944.

In 1940 Lida married Naphtali Goldstein in Eretz Israel, and moved with him to Heftziba. The couple had three children, but fate turned against Lida again. Her husband Naphtali died five years after they had married and Lida, a young woman of 25, and a mother of three small children who had lost her entire family, was once agian left alone. There was no one with whom to share the burden of everyday life and the pain of loneliness.

In 2004, Lida’s children visited the village where she had been born to explore their family history. They were accompanied by Astrid, the daughter of Oscar, Maks’s brother who had married a non-Jewish woman named Maria in 1940, and moved to England. Lida and her uncle’s family had stayed in touch throughout the years.

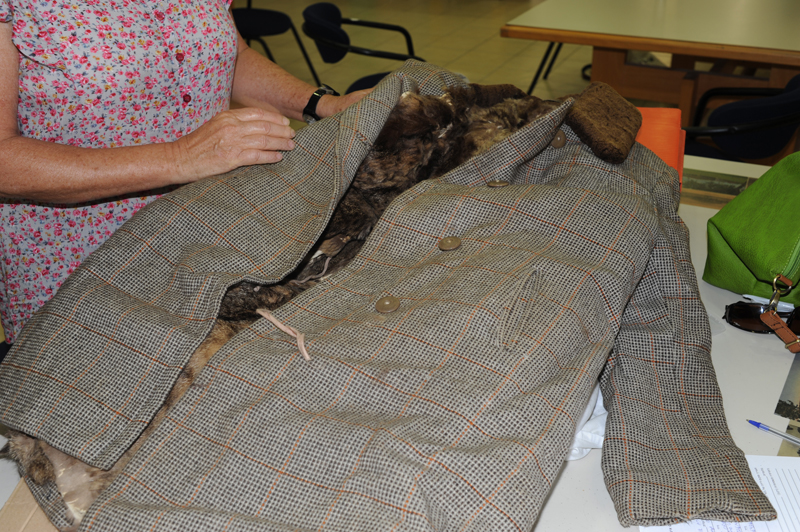

Astrid married a Czech man called Slavik from her father’s village of Kněždub, and she lives there today. She arranged for the family to tour the nearby town of Strážnice, guided by Dr Pajer who lives near the regional Jewish cemetery. Fanny Andriskova, a local resident, heard from him about the visit of members of the Felsenberg family. Until that point, Fanny hadn’t known that any of the family had survived. Finally she could return an item that she had kept in her home throughout the years. Fanny made contact with the family and informed them that in her home she had a coat that her friend Anda had given her before she was deported to Theresienstadt. Sixty years after she was murdered, Anda’s coat was returned to her family in Israel. The family donated the coat to Yad Vashem for posterity.