Today, 24 February, is my birthday;

I am 17 years old today.

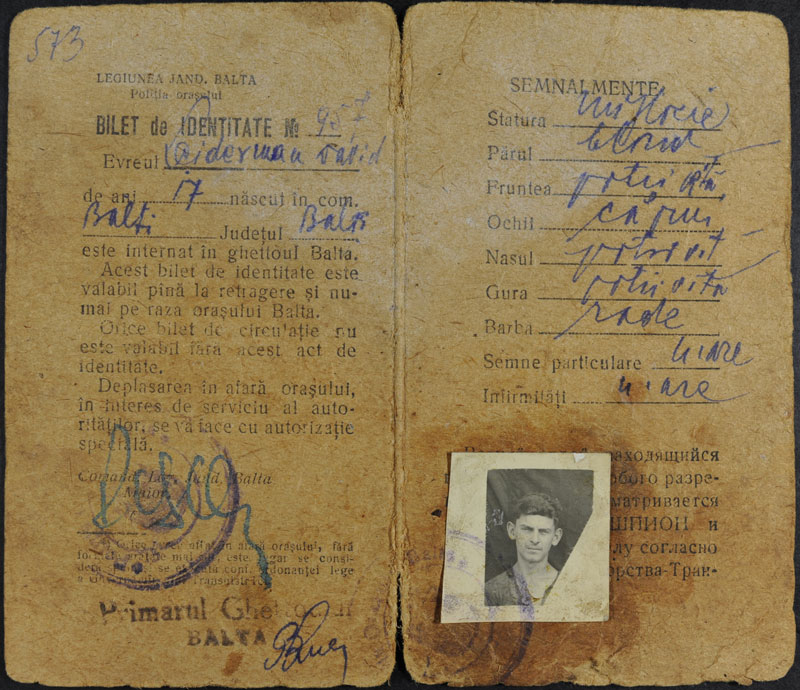

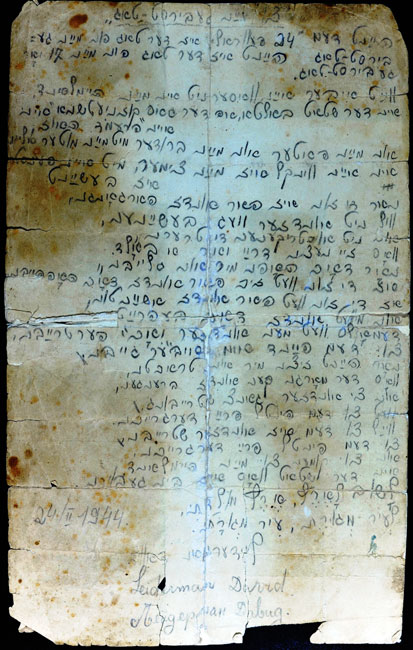

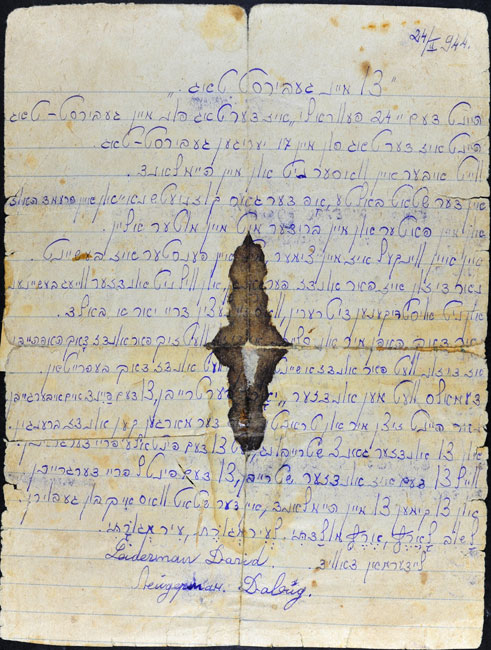

This is the opening line of the poem that David Leiderman dedicated to himself for his birthday, 24 February 1944, in the Balta ghetto in Transnistria.

David was Zalman and Yenta’s second son and a younger brother to Tzvi (Hershel). The Leiderman family lived in the town of Capresti in Bessarabia, Romania.

In the summer of 1941, the Germans and Romanians conquered the area from the Soviet Union. Tzvi, aged 19, was immediately conscripted to the Red Army and all contact with him was severed. The parents, Zalman and Yenta, together with their 14-year-old son David joined the stream of refugees fleeing for their lives to the East, in a futile attempt to escape the German occupation. After two weeks of flight under heavy shelling, they were caught and sent to ghettos that had been established in Transnistria.

One night, when they were trying to escape, David’s father Zalman was shot dead by Romanian soldiers. Yenta and David were sent to a ghetto in the city of Balta, some 150km north of Odessa. Thousands of Jews in the ghettos of Transnistria fell victim to hunger, disease and forced labor. In the indescribable reality of life in the ghetto, young David was dignified and caring. He helped the weak and encouraged the despondent. His young age provided him with two opportunities to leave the ghetto – once an escape to partisans in the forests, and a second time as part of a group of 2000 orphans from Transnistria who were transferred to Romania in exchange for gold, as part of the deal between the fascist government of Romania and the Rescue Committee of Romania. On both occasions David refused to abandon his mother.

Here, in the city of Balta, Kozianshna Street, the house is strange to me.

Without my father, without my brother – only my mother.

My room has been reduced to just one corner

But when its window is lit,

The sunlight

Doesn’t reach us at all.

The sun refuses to light our way

And isn’t prepared to wipe our tears

The tears that have been streaming from our eyes for the past three years.

What does a young man wish for himself on the third birthday that he is celebrating in the ghetto? From the birthday message that he wrote to himself we learn that he continued to hope, even though conditions in the ghetto had deteriorated further:

Despite everything, we hope and believe that the sunlight

Will shine on us and we will be liberated.

Then the despair will be removed from our hearts

And will be transferred to the enemy’s soul.At the moment we sit and wonder:

What can tomorrow bring in its wake?

To realise our dreams

And to reach the day of liberation?

Our aspirations are focused on one pinprick

Of hope –To leave the constraints

And return to my homeland –

To the city where I was born.

To return to the land, the land that I know –

To the city that I know, to the city that I know.

David’s dreams were not to be. On 27 March 1944, a month after his 17th birthday and not long before the liberation of Transnistria by the Red Army, the Germans murdered all men of fighting age, among them David.

Tzvi, David’s brother serving in the Red Army, fought nearby and heard from survivors that his mother was in the Balta ghetto. He managed to obtain a few hours furlough and went to visit her. Yenta told him about his father and brother, and showed him the birthday message that David had written to himself. Tzvi copied it down, left his mother and returned to war.

Towards the end of the war, he was seriously injured but somehow managed to keep the letter in the shirt pocket of his uniform. At the end of the war, Tzvi returned home completely blind; he had with him his brother’s letter, stained with his own blood.

Nachum, Tzvi’s son relates, "When I was a child, I heard innumerable times from my grandmother about the uncle that I had never met – David. She would wake from yet another night filled with nightmares that the Germans were shooting him… Grandma never told me about the letter that he wrote.

Only in 1972, a day before we left the Soviet Union, did she take out the ‘Holy of Holies’ – the original letter, the copy of it and the prisoner ID card that David had been given in the ghetto. All this was sewn into a hidden panel of her handbag, and that is how we crossed the border on our way to Israel."

Nachum donated David’s prisoner ID card to Yad Vashem, as well as the poem that he wrote to himself for his birthday and the copy that his father Tzvi carried with him until the end of the war.