The Yad Vashem Archives Division is responsible for the preservation of millions of documents from the period of WWII, including hundreds of personal diaries written during the Holocaust. One such diary was penned by Rabbi Uri Feivish Tauber, from 1941 to1944, in Mogilev-Podolski. Born in 1911 in Cerepcauti, Romania, the rabbi was deported to Mogilev in October 1941, and stayed there until the city was liberated by the Red Army. The diary was recently presented to Yad Vashem by his widow Ruth Tauber, in the hope that it would be preserved for eternity.

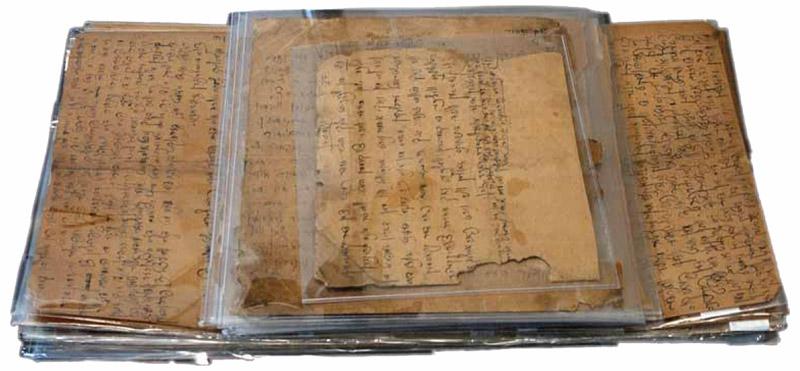

The crumbling diary was first handed to the Archives for restoration and preservation. Some of its pages had been damaged by acidity, were disintegrating, and were covered with adhesive tape, whose chemical components had caused further damage. The Preservation Laboratory team worked hard to save the pages, and its complete restoration will now ensure the diary’s accessibility to the general public.

Mogilev, a city on the Dniester River in the province of Vinnitsa in Ukraine, was conquered by the Germans on 19 July 1941. It soon became a center for Jews deported from Bessarabia and Bukovina, and was one of the five points of entry to Transnistria, the area in western Ukraine that Hitler ceded to Romania in return for its participation in the war against the Soviet Union. Tens of thousands of Jews passed through the city, but only about 12,000- 15,000 of the deportees managed to remain, joining some 3,700 local Jews.

In July 1942, a ghetto was established in the city, surrounded by a wall and a barbed wire fence. Living conditions were harsh, with overcrowding, hunger and poverty. A typhus epidemic caused many deaths within just a few months. The Jewish leadership established a central Jewish committee for the entire province, which created various welfare institutions, including three orphanages. The children’s living conditions were extremely difficult: they existed in a wretched state, hungry and ill. Only after several months did their physical condition improve, allowing the directors of the orphanages to devote more time to their education. Rabbi Tauber joined in this educational activity at Orphanage No. 1, which opened in April 1942 and by August housed some 450 orphans. Rabbi Tauber was part of the orphanage staff, teaching Hebrew and Bible until 1944, when the orphanage was closed, and the children sent to Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine).

In a notebook given to him as a souvenir, the children wrote that he had been a “good father” to them. One woman, who had been a child in the orphanage, later related that the rabbi had given them hope that they would go to Eretz Israel after the war.

Rabbi Tauber began to write his diary—in German with Hebrew lettering—in October 1941. Inside, he tells of the daily hardships in the ghetto, stories he heard from various people, and events that occurred there: Jews in hiding; a child who saved his mother’s life; the death of 15-year-old Poldi Lazarovitch, a member of the orphanage’s journal "editorial board;" the bitter cold and the shortage of salt; a celebration on the first night of Hanukkah; and much more.

In one diary entry, Rabbi Tauber describes the lighting of Hanukkah candles in the orphanage. A large party was held in the orphanage on the first night of Hanukkah. The large hall was cleared and they sang Hanerot Hallalu, Maoz Tsur and Techezekna among other songs, and discussed the meaning of the holiday. They ended the evening by singing Hatikva.

This personal document sheds light on the life of Jews in the Mogilev ghetto, as seen through the eyes of its author—a beloved teacher dedicated to his pupils. Its preservation will enable the public to enrich their knowledge of the events in Mogilev, and thus gain a more complete picture of Jewish life in this area during the war.

"I knew that if I kept the diary, it would disintegrate," Ruth Tauber explained. "The pages had begun to crumble and I didn’t have the facilities to preserve it. I didn’t want it to be lost forever. At Yad Vashem it is much safer than in my own home." In addition, she said, "In my house, in a drawer, nobody would see it, but at Yad Vashem others can read it and learn about everything that happened. That way, the diary will be a reminder for all time."