Dwora’s first memory is of herself alone at night, standing and crying in the garden of a strange house, where her mother had left her before she disappeared. At the time, Dwora was about two-and-a-half years old.

Dwora discovered everything that had preceded that night from her mother later on:

Dwora Rozencvaig née Winokur was born in 1941 in Widze, Lithuania to Shmuel and Bela, a younger sister for their son Shlomo. In February 1942 they were incarcerated in a ghetto together with all the Widze Jews. In December 1942 they were transferred from there to the Swiecany ghetto and in April 1943, to the Vilna ghetto. When the Vilna ghetto was liquidated in September 1943, the family was sent to Ponary. At the mouth of the pit, Bela convinced her husband to escape. Carrying their children, they fledin the direction of the forest. Shmuel and Shlomo fell, but Bela continued running until she fell next to a tree. A bullet hit the tree; as the Germans stopped shooting, it appears that they assumed that Bela had been shot. Bela lay on top of her baby daughter for hours and then began walking in the forest. A few days later they reached another ghetto. The Jews from that ghetto were also taken to be murdered in the nearby forest; on this occasion, Bela managed to hide with her daughter under a pile of leaves. Having survived the aktion, they began wandering the forest again, without even a ghetto to return to. How can a person hide with a small girl? Bela recalls that people she met told her, “Leave her, why are you carrying a baby around with you? Save yourself!” Mother and daughter wandered in the forest, in the snow, frozen from the cold, starving and infested with lice. Now and again, Bela would knock on the door of a house in the hope of receiving something to eat. Occasionally she found frozen fruit in the snow. At night they snuck into barns and cowsheds to sleep.

At some stage the two were caught by Lithuanians. They were brought to the headquarters where they were locked up until their intended execution the following day. Once again, they managed to escape thanks to Bela’s quick thinking and resourcefulness. At this point, exhausted and desperate, she was ready to die, but what could she do with her infant daughter? Bela resolved to find a hiding place for her. At night, in the granaries where they slept, she would teach Dwora Polish so that her Jewish identity would be not be discovered. They returned to Widze, and she brought Dwora to Anna Trabszowa, a non-Jewish woman whom she had known before the war. She asked Trabszowa to save her daughter, but fearing for her life, Trabszowa refused to take in the child. Bela pleaded with her, but to no avail. That night she left, leaving her daughter crying bitterly in the garden. Some time later, Trabszowa went out into the garden and took Dwora into her home. Bela, who had been planning to hang herself, abandoned the idea out of concern for her daughter, who had no one else in the world but her.

The following morning Trabszowa took Dwora to the Lithuanian authorities and told them that she had found a girl. As Dwora was fair, the Lithuanians were convinced that she was not Jewish. Trabszowa was granted permission to look after her and even received financial assistance for doing so.

Dwora enjoyed playing with the animals in the farm, and ate well there. Sometimes she would go out to work with the family in the fields, but on other occasions, they would go without her and leave her alone in the house for days at a time. She loved going to church and dreamed of the day when she would have her confirmation ceremony.

All this time, her mother hid with Lula Matecko, who generously shared with her the little food that she had. She even made occasional secret visits to Dwora and brought news of her to her mother.

At the end of the war, Bela wasn’t sure if it was fair to bring her daughter back to the Jewish faith after all she had gone through during the war, but she finally decided that she couldn’t give up on Dwora, the only surviving member of her large family. Meanwhile, Trabszowa had become very attached to Dwora and feared that she would be taken from her. Towards the end of the war, Trabszowa had asked the local priest to baptise Dwora, but the priest refused, saying that he would only baptise her if nobody came to claim her at the end of the war.

When Bela came to take back her daughter, Anna said to her, “Hitler murdered six million Jews and only you had to survive?” She claimed that as she had raised Danka (Dwora), she was her daughter now and she was not going to give her up. Danka ran to her room and brought a small cross and hurled it at her mother, “You see what your Jews did to our Jesus?” She was filled with fear and disgust for her mother, “as if the sky had fallen on me,” and refused to go with her. Bela did not give up and stayed in Widze for a year, in an attempt to be accepted by her daughter. Eventually, Dwora understood that she had no choice: she joined her mother and the two went to Bialystok.

Bella learnt that Taibele Volovitz, a relative’s daughter had been hidden with non-Jews at the age of three months and had survived; her parents had been murdered. Bela managed to locate the girl who had been severely neglected. Once more, she was forced to struggle with the girl and her rescuers in order to retrieve her. In accordance with the wishes of her family in Eretz Israel (Mandatory Palestine), Taibele immigrated to Eretz Israel through the Youth Aliyah program.

From Bialystok, Dwora and her mother moved to Lodz. Bela remarried, to a Holocaust survivor who had lost his wife and three children. At the age of forty-five she discovered that she was pregnant, and decided to have the baby despite her fears, so that her daughter would have a close relative. Miriam was born in 1950 and the family immigrated to Israel in 1957.

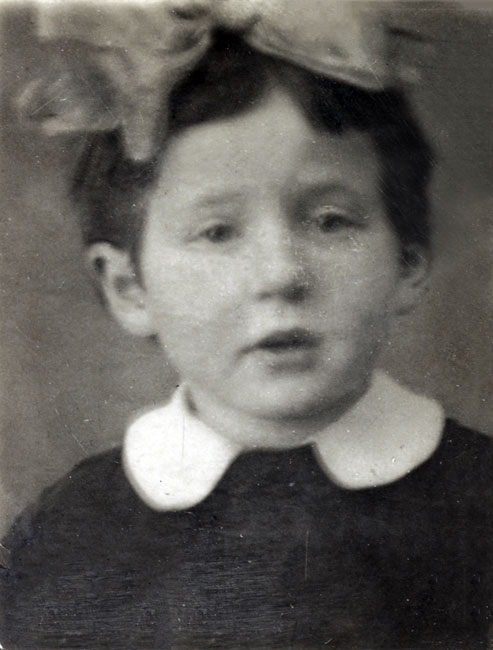

Among the photographs that Dwora donated to Yad Vashem is a photograph of her parents, Shmuel and Bela, a photograph of her father Shmuel with her brother Shlomo, a photograph of her as a child in hiding and a photograph of her rescuer, Anna Trabszowa.