Giulia chose to join her daughter Anna in the Fossoli di Carpi concentration camp and was murdered there

Sunday to Thursday: 09:00-17:00

Fridays and Holiday eves: 09:00-14:00

Yad Vashem is closed on Saturdays and all Jewish Holidays.

Entrance to the Holocaust History Museum is not permitted for children under the age of 10. Babies in strollers or carriers will not be permitted to enter.

Giulia chose to join her daughter Anna in the Fossoli di Carpi concentration camp and was murdered there

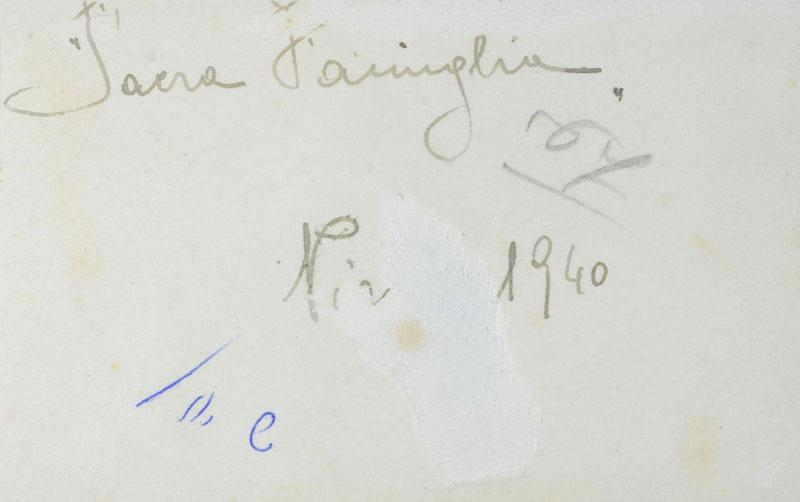

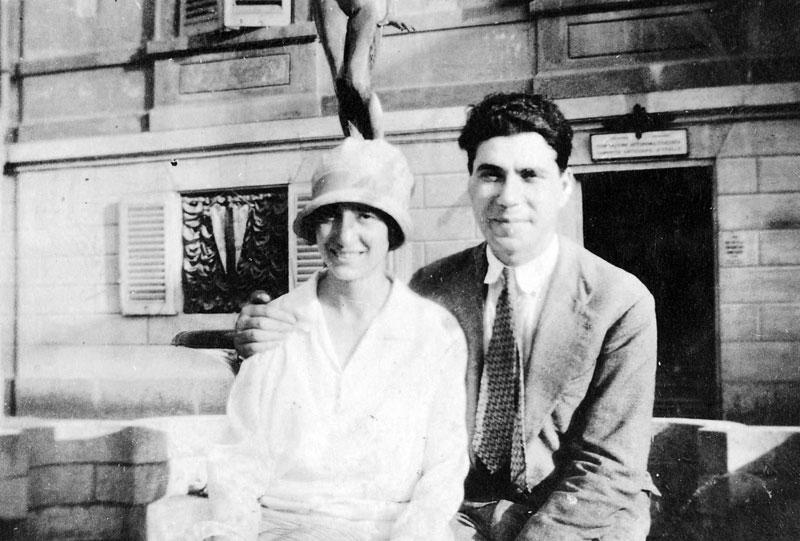

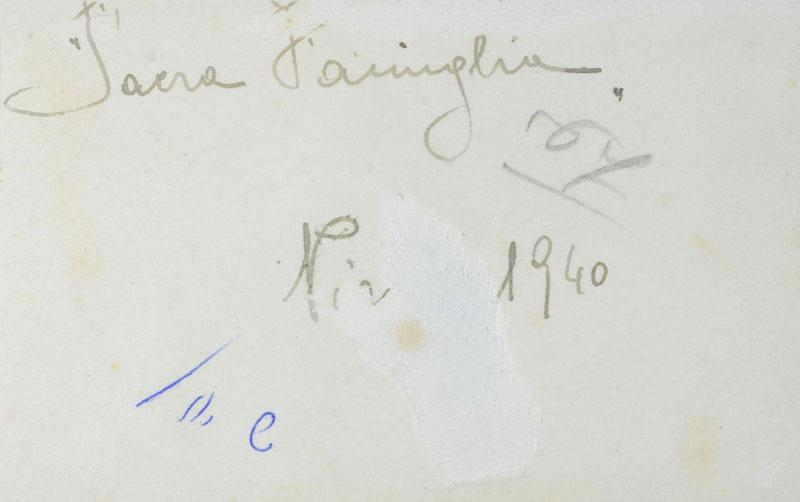

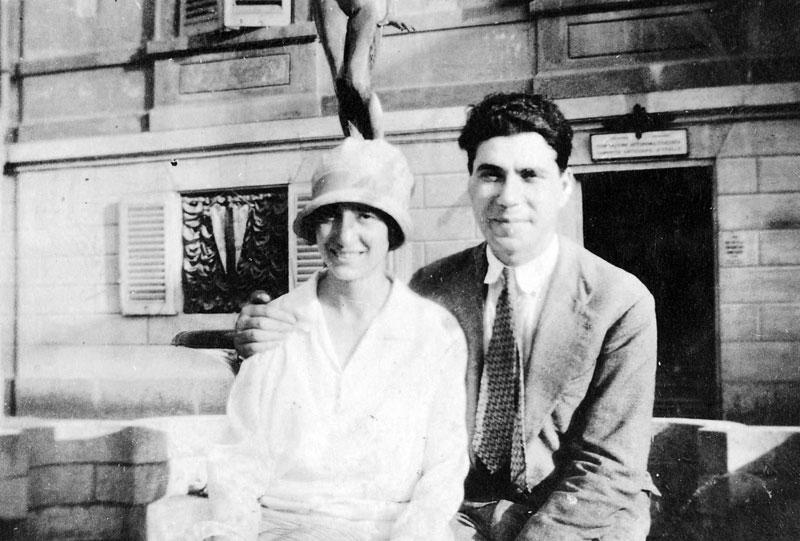

"The holy family" wrote Anna Ventura on the back of the photograph in which she appears with her four children, Miriam, Saul, Daniel and Emmanuele. She sent the photograph to her husband Luigi who was in Paris at the time.

Four years later, from the Fossoli di Carpi concentration camp where Italian Jews were detained before their deportation to Auschwitz, Anna wrote to her husband and children who remained in Milan:

10.1.1944

…My little lady (Miriam Shulamit) is always at the forefront of my mind, I am certain that the excellent Saul will cooperate with her diligently and faithfully. I rely on Daniel’s quick-wittedness and that he knows how to be a friend and protector for Emmanuele, the small and the brave. I think about you day and night.

What I am undergoing is the most difficult kind of test, but I have faith that God will give all of us the strength to overcome it and that we will be able to return to our family life, which is so dear to our hearts.

Anna’s prayer for the reunification of her family was not answered. On 22 February 1944 the camp inmates were deported to Auschwitz. Author Primo Levi was among the camp inmates, he wrote of their last night in the camp:

But on the morning of the 21st we learned that on the following day the Jews would be leaving. All the Jews, without exception. Even the children, even the old, even the ill. Our destination? Nobody knew. We should be prepared for a fortnight of travel. … We knew what departure meant.

…

And night came, and it was such a night that one knew that human eyes would not witness it ¬and survive. Everyone felt this: not one of the guards, neither Italian nor German, had the courage to come and see what men do when they know they have to die.

All took leave from life in the manner which most suited them. Some praying, some deliberately drunk, others lustfully intoxicated for the last time. But the mothers stayed up to prepare the food for the journey with tender care, and washed their children, and packed the luggage;

…

Would you not do the same? If you and your child were going to be killed tomorrow, would you not give him to eat today?

…

Dawn came on us like a betrayer; it seemed as though the new sun rose as an ally of our enemies to assist in our destruction. The different emotions that overcame us, of resignation, of futile rebellion, of religious abandon, of fear, of despair, now joined together after a sleepless night in a collective, uncontrolled panic. The time for mediation, the time for decision was over, and all reason dissolved into a tumult, across which flashed the happy memories of our homes, still so near in time and space, as painful as the thrusts of a sword.

Primo Levi, "If This is a Man – The Truce", Abacus, 1987, p20-22

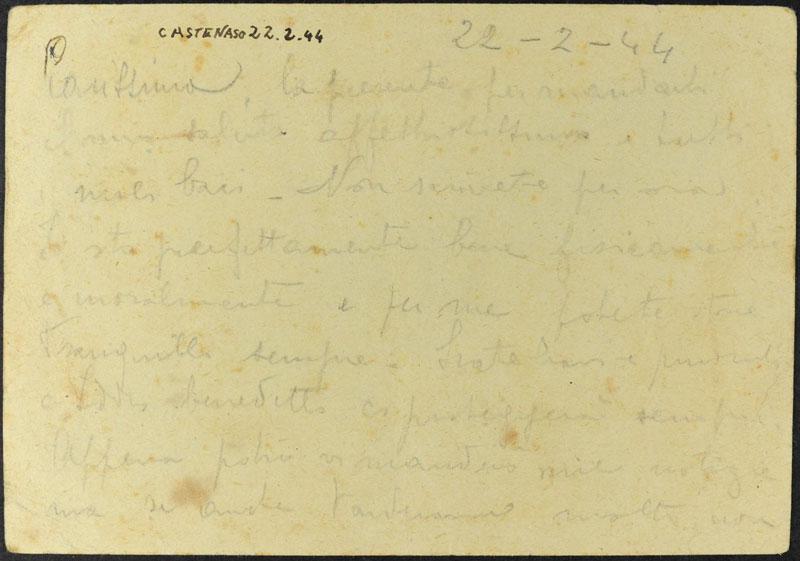

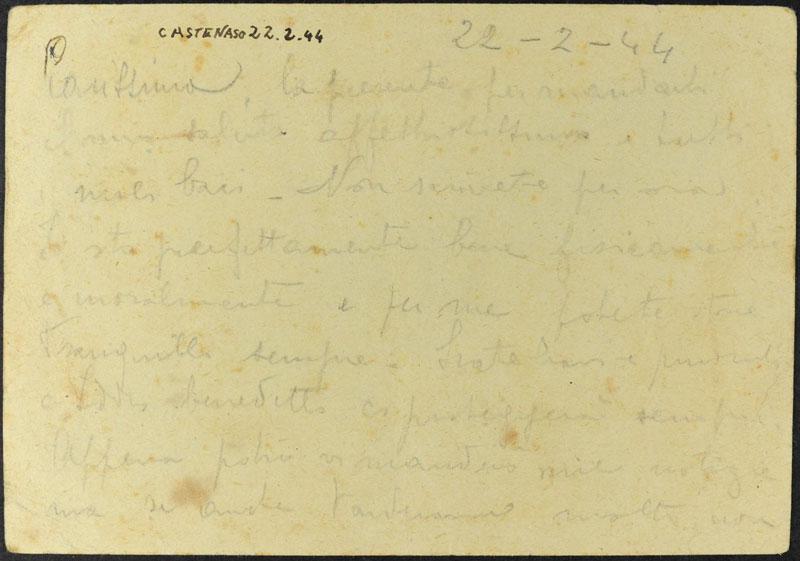

In the postcard that she sent from the nearby village of Castenaso on the day that she left the camp (it is possible that one of the workers at the camp or one of the guards promised to send the letter for her), Anna wrote:

To my very dear ones,

I’m sending you this postcard to send you my blessings, my love and all my kisses. Don’t write to me for now. I feel excellent, both physically and mentally. You can be calm about me forever. Be strong and have faith that the God will always protect us. When I can I will write to you again, but even if much time passes, don’t worry.

Always yours,

Nina

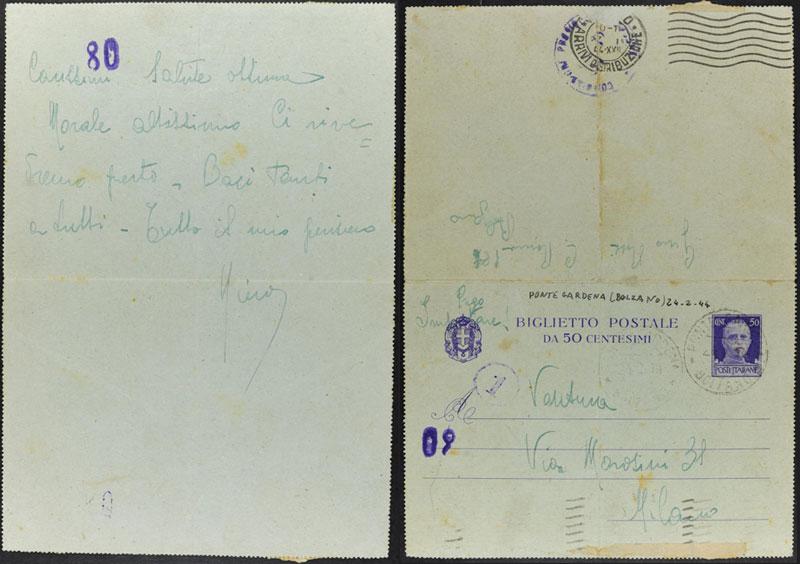

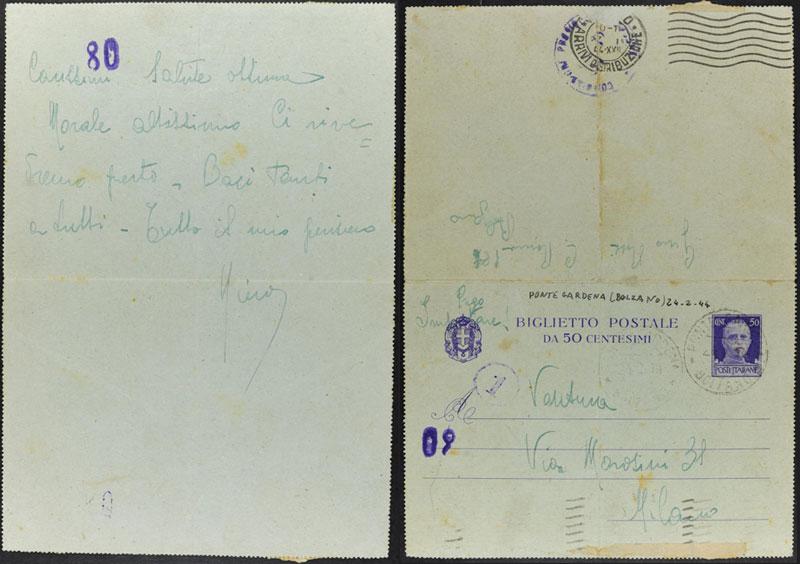

In the final postcard that Luigi and the children received from Anna, there was just one line:

To my very dear ones,

My morale is very high. We will see each other soon. Lots of kisses to everyone. All my thoughts are of you.

Nina

The postcard was thrown from the train at the last minute before it left Italian territory. Anna wrote her request to the unknown finder of the postcard, “Please post this letter!” Fearing that the postcard would not be allowed to reach its destination should the authorities suspect it had been thrown from the window of a train that carried Jews to their deaths, Anna signed the letter with a popular non-Jewish name. As the sender's address, she wrote Bolzano, a city near the border with Austria and Germany, in order to hint to her family where she was being taken.

The postcard was sent on 24 February 1944 from Ponte Gardena in Bolzano. For a long time the family held on to the faint hope that their mother was somewhere in the north and that they would see her again.

Later, they learned the bitter truth. On 26 February 1944, following a five day journey, the train arrived at Auschwitz. Of the 650 Jews deported, 521 Jews were murdered on the day of their arrival at the camp; Anna Ventura was among them. Few survived until the end of the war.

Months earlier, in the first days of January 1944, when searching for a hiding place, Luigi and his children had arrived in Pisa, his birthplace. Luigi hoped that he would be able to get help from old acquaintances in finding a hiding place. He was also hoping to get as close as possible to the Allied Forces who had landed in Southern Italy and were making their way north. At the same time, he did not want to go too great a distance away from his wife Anna, who he was hoping would be released through the intervention of influential women in the area.

An old friend of Luigi, Aron Manoci, gave them the keys to his small house in Marina di Pisa where they arranged a hiding place for themselves.

The eldest daughter Miriam took on the role of being responsible for the welfare, food and clothing of her younger siblings. To earn a living, Saul accompanied his father on journeys between Pisa and Milan. On one such trip, Luigi was injured during an air-raid on the way from Milan to Pisa and he died from his injuries.

The four children were left alone, under sixteen-year-old Miriam’s care. Later, when the house where Saul and Daniel were hiding was damaged in an explosion, Miriam managed to find a hiding place for all four of them in a hospital. They stayed there until the liberation on 2 September 1944. From Pisa they went to Florence, where the youngest brother, six-year-old Emmanuele, died from diphtheria. On 25 March 1945 Miriam, Saul and Daniel Ventura immigrated to Eretz Israel with the help of Beit HeHalutz in Florence.

Saul Ventura donated the letters that their mother had sent after her arrest, to Yad Vashem. Among them was the final postcard that she threw from the deportation train, together with the plea to the unknown finder, “Please post this letter!”

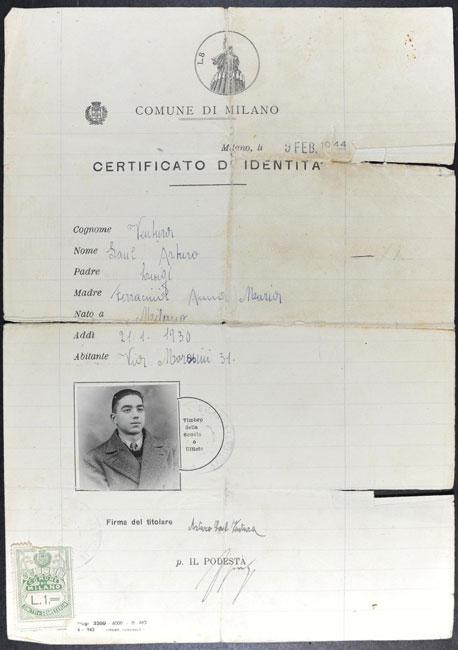

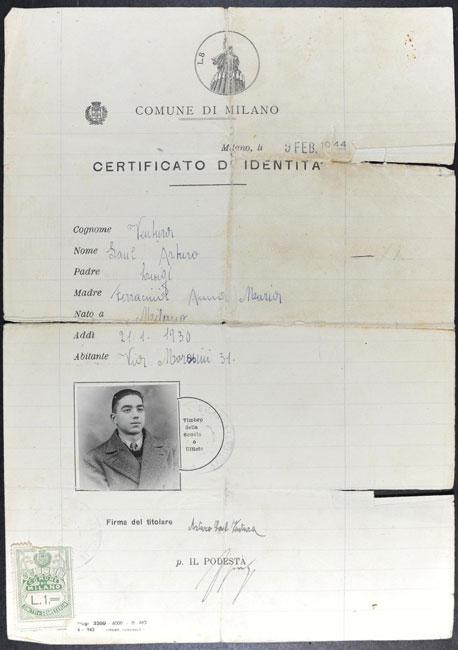

Among the other documents that he donated is the identity card that he took when accompanying his father on his missions to bring medicines from Milan to Pisa. The stamp “Ebraica Razza”, identifying him as a Jew, had appeared on the document; thanks to his experience as a chemist, his father had been able to remove the stamp.

Thank you for registering to receive information from Yad Vashem.

You will receive periodic updates regarding recent events, publications and new initiatives.

"The work of Yad Vashem is critical and necessary to remind the world of the consequences of hate"

Paul Daly

#GivingTuesday

Donate to Educate Against Hate

Worldwide antisemitism is on the rise.

At Yad Vashem, we strive to make the world a better place by combating antisemitism through teacher training, international lectures and workshops and online courses.

We need you to partner with us in this vital mission to #EducateAgainstHate

The good news:

The Yad Vashem website had recently undergone a major upgrade!

The less good news:

The page you are looking for has apparently been moved.

We are therefore redirecting you to what we hope will be a useful landing page.

For any questions/clarifications/problems, please contact: webmaster@yadvashem.org.il

Press the X button to continue